- Increases the Uniform Per Student Funding Formula (UPSFF) by 3 percent, bringing the per-student funding base to $11,310.

- Minimally increases the supplemental at-risk weight in the UPSFF.

- Provides $6.9 million to DC Public Schools (DCPS) to increase student access to technology and the internet, significantly less than what digital equity advocates say is needed for all students to have their own device to engage in virtual earning this school year.

- Invests $3.3 million to expand the District’s school-based mental health program to 47 additional traditional and public charter schools.

- Transfers the management of DCPS’ security guard contract from the Metropolitan Police Department to DCPS and redirects $4.1 million from the contract to support social-emotional learning resources for students.

- Maintains grantmaking funds for Out-of-School Time programs and includes a small increase for middle school youth mentoring programs.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forever changed public education but to what extent remains unknown as the virus continues to spread. Earlier this year, District and education leaders made the difficult, but necessary, decision to shutter schools and initiate virtual learning in order to save lives. DC Public School (DCPS) students will start the 2020-21 school year completely virtual while some public charter schools will offer hybrid learning models (in-person and online).

The fiscal year (FY) 2021 approved budget makes notable investments in public education, including new investments in per-pupil funding, school-based mental health, and social-emotional learning at a time when the District is facing massive revenue loss.[1] Still, the health crisis and pandemic-induced economic shutdown has likely deepened the already unacceptable racial and income inequities in student outcomes and will require policymakers to make greater investments in schools and other public services that vulnerable families need.

Before the pandemic, policymakers’ failure to adequately fund schools has resulted in too few “at-risk” students—such as low-income students—and students of color being prepared for success in the classroom and beyond. In the 2019-20 school year, only 19 percent of at-risk students were college- and career-ready in math and English compared to 45 percent of their non-at-risk peers. In the same year, only 25 percent of Black students and 34 percent of Latinx students were college- and career-ready, compared with 83 percent of white students.[2]

With Black and Latinx households bearing the brunt of COVID cases and deaths in DC[3]—many of them low income and lacking proper social and economic safety nets—schools will face even more challenges in helping students overcome longstanding and newly erected barriers to learning. Policymakers will need to make more progress toward adequately and equitably funding schools in the future, and they should track the pandemic’s effect on students to better ensure that they are receiving the supports that they need.

Budget Narrows Adequacy Gap in Per-Student Funding, More Progress Is Needed

The approved budget includes $994 million in local revenue for DCPS, a 7 percent increase over FY 2020, adjusted for inflation. The approved budget includes $934.9 million in local revenue for public charter schools, a 2 percent increase, adjusted for inflation.

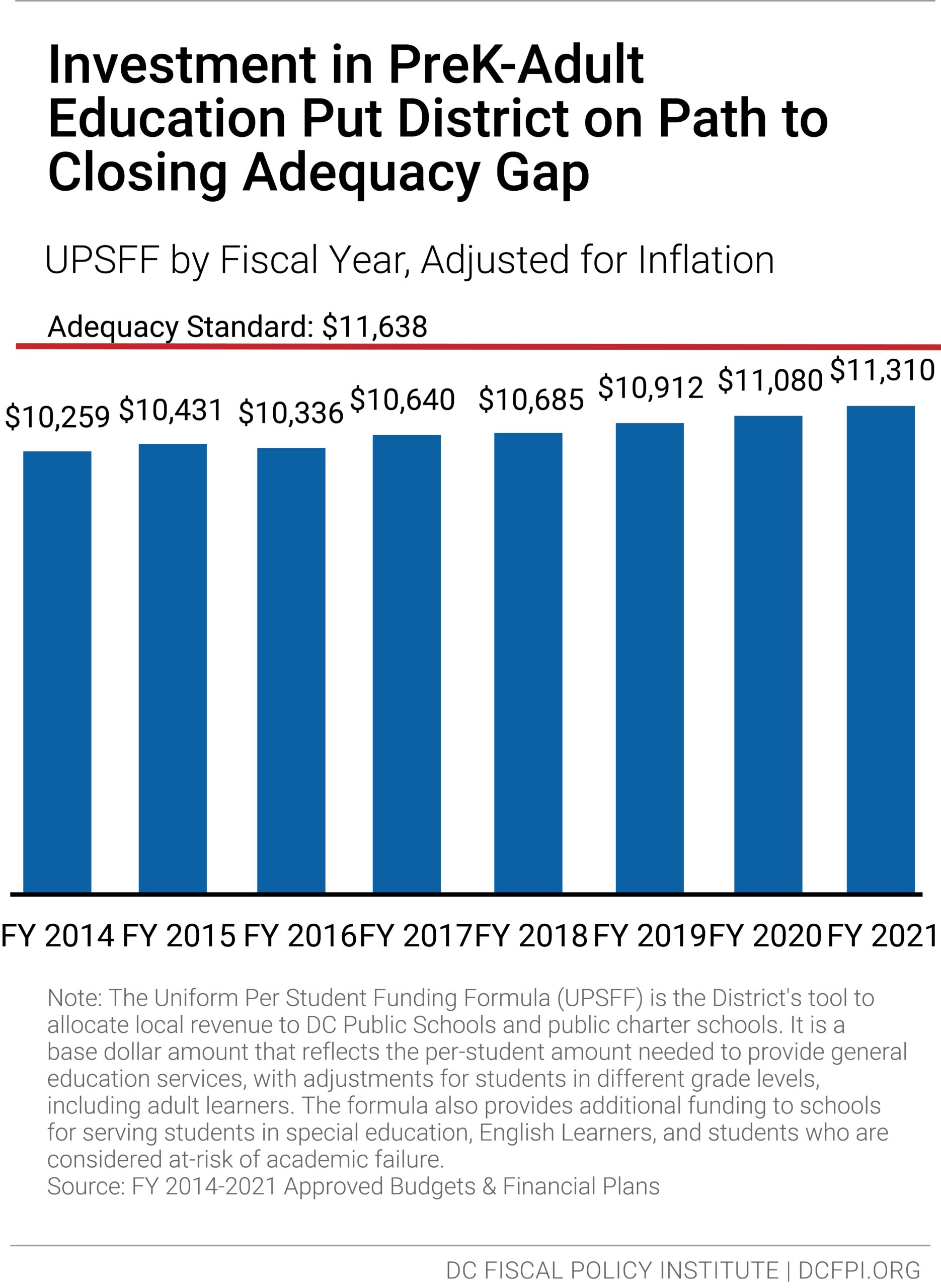

Driving these budget increases is a 3 percent increase to the Uniform Per Student Funding Formula (UPSFF), raising the per-student base amount for the 2020-21 school year from $10,980 to $11,310. However, when adjusted for inflation, the increase is only two percent. The UPSFF is the District’s main tool for allocating local revenue to the nearly 100,000 students who attend DCPS and public charter schools. It includes a base funding amount that reflects the per-student amount needed to provide general education services, with adjustments for students in different grade levels, including adult learners. The formula also provides additional funding to provide targeted resources to students in special education, English Learners (ELs), and at-risk students.

The 3 percent increase to the UPSFF is impressive given the revenue losses the District is experiencing and narrows the gap between the recommended funding level in the 2013 DC Education Adequacy Study (Adequacy Study) commissioned by the DC government.[4] Still, the per-pupil amount is below the recommended level for the eighth fiscal year in a row. The recommended base amount is $11,638—when adjusted for inflation to FY 2021 dollars—which means the approved FY 2021 UPSFF is $328, or 3 percent, lower than the recommended level (Figure 1).

Policymakers have never fully funded the UPSFF at the recommended level, which has contributed to inadequate per-student funding for basic educational services, and school officials being forced to pit one priority against another in order to stretch their budgets. Facing budget pressure, DCPS has routinely diverted its at-risk funds to cover core programming and staffing positions, such as art teachers and librarians, instead of giving these funds to schools for their intended purpose. This practice occurs despite laws explicitly requiring DCPS to add to, not replace, school budgets with at-risk funds.[5]

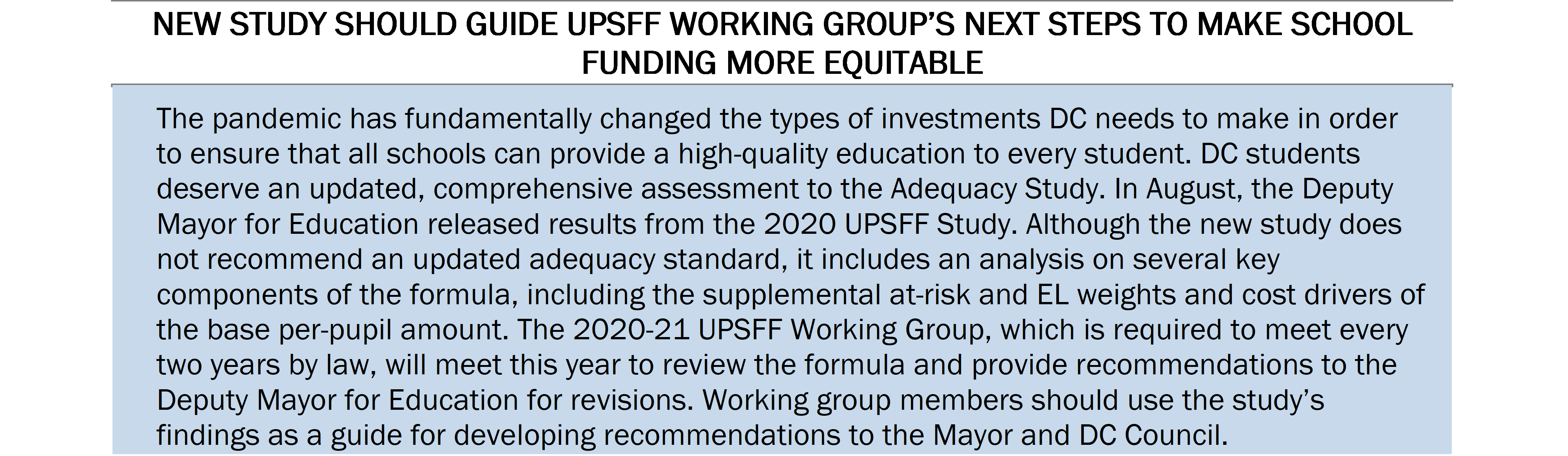

As District officials, parents, school leaders and educators grapple with the unknowns of the virus, the approved budget was a missed opportunity for District leaders to raise sufficient revenue and make proactive investments for the added costs that schools are likely to incur should more students begin going back to classrooms. For example, 31 out of 123 public charter schools do not have a school nurse, leaving these schools ill-equipped to sufficiently monitor students’ and staff members’ health or respond to and help contain potential outbreaks in schools (Figure 2).

Budget Minimally Increases At-Risk Weight, Provides No Increase to English Learners Weight

Like the base per-student funding in the UPSFF, the supplemental and at-risk and ELs weights remain below recommended levels in the Adequacy Study.

The approved budget slightly increases the at-risk weight to .2256 from .225 for low-income students and other students at risk of falling behind academically enrolled at DCPS and public charter schools. Schools will receive $2,551 per at-risk student in FY 2021, totaling $106.7 million in at-risk funding. Total funding will decrease by two percent—when adjusted for inflation—compared to FY 2020 due to a decline in the projected number of at-risk students. DC considers a student at-risk if they are in foster care, experiencing homelessness, over age for their grade in high school, or live in family participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. The majority of students considered at-risk are Black and brown, reflecting the enduring legacy of racism, housing discrimination, and economic exploitation and exclusion in DC.

DCPS is projected to serve 24,245 at-risk students, and public charter schools are projected to serve 17,515. However, given the pandemic, it is possible that there will be some movement of students between sectors, and as more families lose their financial stability and face evictions, food insecurity, and other challenges, schools will serve more at-risk students than originally projected.

The approved budget does not increase the ELs weight, which provides additional funding for students who are learning English. DCPS and public charter schools will receive $5,542 per EL student in FY 2021, totaling $69.4 million. This represents a 14 percent increase over FY 2020, when adjusted for inflation, and reflects enrollment growth of EL students in both sectors.

The Adequacy Study and advocates have long called for improvements to the ELs weight, namely by making the weight tiered to accommodate EL students with varying levels of proficiency. Currently, the District either identifies a student as an EL or not and provides the same amount of funding per EL student regardless of their level of proficiency. Further, with many of the District’s immigrant families facing extreme financial hardship—including being left out of federal economic relief efforts[6]—policymakers missed an opportunity to increase the resources that EL students need to thrive.

DC Expected to Receive Nearly $50 Million in Federal K-12 Education Relief, Some Charters Received Paycheck Protection Program Loans

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act includes two main sources of federal relief for K-12 education: The Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) Fund and the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief (GEER) Fund. The District’s Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) is expected to receive $42 million in ESSER funds and $5.8 million in GEER funds.[7] The CARES Act gives states and DC considerable discretion over these funds, although they are expected to issue ESSER funds to local education agencies to pay for COVID-19 specific needs, such as purchasing devices for students, cleaning and sanitizing supplies, or targeted resources for vulnerable students such as those who are low-income or EL students.

While District and education leaders have indicated some uses of these federal relief dollars (read more in the sections below), overall, there is limited transparency around how these resources are being spent.

Twenty-seven public charter school LEAs—which operate as nonprofits—received business loans greater than $150,000 through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP).[8] The CARES Act authorized the program, which is designed to help small businesses and nonprofits maintain payroll and retain staff during the COVID-19 pandemic.[9] In total, these LEAs received between $19 million and $45 million in federal relief.[10]

Capital Budget Adds Funding for Additional Early Childhood Seats in DCPS

The approved budget invests $75 million in capital funding to add 540 new early childhood seats and 180 pre-kindergarten seats at several DCPS schools across the District.[11]

While this is a strong investment and more quality seats are needed to support DC’s long-term early childcare ecosystem, the budget should also provide funding to address immediate needs to support the growing childcare shortage stemming from COVID-19 (see DCFPI’s Early Childhood Development Toolkit to learn more about what is in the budget for early childhood education).

Some New Money for School Technology, But Digital Divide Will Likely Persist

The approved budget includes $6.9 million to fund the second year of the Empowered Learners Initiative (ELi), Mayor Bowser’s three-year commitment to ensuring that there is a 1:1 student-to-device ratio for third through twelfth grade DCPS students.[12] DCPS will leverage $4.9 million of the federal ESSER Fund money it received to purchase more devices and hotspots.[13] In total, DCPS will invest $17 million in technology[14], which reflects the new investments in ELi, federal funding, and some other undisclosed sources of money. DCPS distributed over 10,000 devices and 5,500 Wi-Fi hotspots during the last semester of the 2019-20 school year.[15] DCPS expects to have at least 45,000 devices and an additional 3,500 hotspots available for the 2020-21 school year and has made a commitment “to providing a device for any student who needs one.”[16]

OSSE will spend $3.3 million of the GEER funding it received to provide internet access to families with school-aged children in both sectors, particularly those that qualify for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.[17] Lastly, the Mayor will use the newly-launched DC Education Equity Fund to continue raising additional money to increase student access to internet and technology devices such as tablets or laptops.[18]

Despite these investments, many families, advocates, teachers, and school leaders remain deeply concerned about the ways in which the pandemic is further exposing and worsening the District’s existing digital divide.

The digital divide—the gap between people with reliable access to digital technologies and the internet and those who do not—is a pervasive issue in the District. Access is highly correlated with education, income, and place, with lower-income residents and people living in Wards 5,7 and 8 having less access than their wealthier neighbors living in Wards 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6.[19] Black and Latinx DC residents are more likely to access the internet via mobile phones—an inadequate substitute for homebased internet—and are more likely to access the internet elsewhere such as a library.[20] With public libraries and other public options shut down or operating on limited schedules due to the pandemic, many low-income families and families of color are relying on schools to provide the tools their children need to have a successful virtual learning experience

When the District first shuttered school doors in March, DCPS Chancellor Ferebee estimated that 30 percent of the system’s students did not have access to internet-enabled devices, according to an informal family survey.[21] However, preliminary results from a new, formal survey show that a larger percentage of families than previously indicated need devices for their students, giving the public reason to believe that the actual need is much larger than is accounted for in the approved budget.[22]

There is currently no publicly available estimate of the technology needs within the charter school sector. However, there are likely thousands of students facing similar disadvantages in technology access given almost half of the sector’s student population is low-income or facing some other challenge such as homelessness.

It is notable that the Mayor and DC Council made new investments toward increasing students’ access to devices and the internet. Still, given the new learning reality, it is likely that more investments are needed to ensure that every student has access to virtual learning tools and supports. Beyond devices and reliable internet, additional resources are likely needed for enhanced technical support for students, families, and teachers, device repairs and replacements, and any other foreseeable costs associated with bringing all of the District’s nearly 100,000 public school students online.

Budget Necessarily Expands School Mental Health Resources

The approved budget includes $3.3 million—including $75,000 in one-time funding—to expand the Department of Behavioral Health’s (DBH) School Mental Health Program (SMHP) to more DCPS and public charter schools.[23] This investment falls just below school mental health advocates’ ask of $4 million. The goal of the SMHP is to provide coordinated and integrated mental and behavioral health resources to help improve student academic and health outcomes. The program primarily achieves this goal by awarding grants to community-based behavioral health organizations (CBOs) that place licensed mental health professionals in schools who provide prevention and intervention services such as parent and teacher consultations and crisis management. The new funding will allow DBH to expand the program to 47 additional schools in the 2020-21 school year, bringing the total number of participating schools to 161.[24]

District leaders have also designated $1.5 million of the District’s GEER Funds to support student mental health.[25] It is unclear how officials will spend this one-time funding, but possible uses include providing a one-year subsidy to CBOs to cover COVID-19 related costs or support the expansion of SMHP.

Now more than ever, adequate mental health supports for students are crucial to helping students navigate and cope with the ongoing disruptions they are experiencing in their academic and social lives. Even more, as families confront high stress levels, increased economic insecurity, and inadequate social support—known risk factors for child abuse and neglect—mental health supports outside of school are equally vital in helping families stay whole. (See DCFPI’s safety net approved budget toolkit to learn more about what is in the budget for community-based behavioral health services).

Budget Shifts Management of DCPS Security Contract and Adds New Dollars for Social-Emotional Learning

The FY 2021 budget season was marked by national and local protests against police brutality and tens of thousands of DC residents’ calls to divest from or defund the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). The youth of Black Swan Academy led a successful #PoliceFreeSchools campaign on social media that helped convince the DC Council to end MPD’s management of DCPS’s $23 million school security contract, giving that responsibility to the school system.[26] The DC Council also redirected $4.1 million of the contract funding to schools to increase investments in social-emotional learning opportunities for students. Removing police from schools is one of many steps needed to ensure the city prioritizes education over incarceration and is supported by DC residents.[27]

The approved budget also includes $13.9 million in MPD’s School Safety Division to pay for the District’s 100 school resource officers (SROs) that patrol both DCPS and public charter schools. This represents a 22 percent increase over the FY 2020 budget. The approved budget also invests $1.5 million for OSSE’s School Safety and Positive School Climate Fund— including an increase of $150,000 by the Council to the Mayor’s proposed budget—but represents an overall 7 percent decrease over the FY 2020 approved budget when adjusted for inflation.[28] This fund aims to support schools in “implementing strategies to reduce suspensions and expulsions and facilitate training and technical assistance in positive behavioral interventions” and was established through the 2018 Student Fair Access to Schools Act (SFASA).[29]

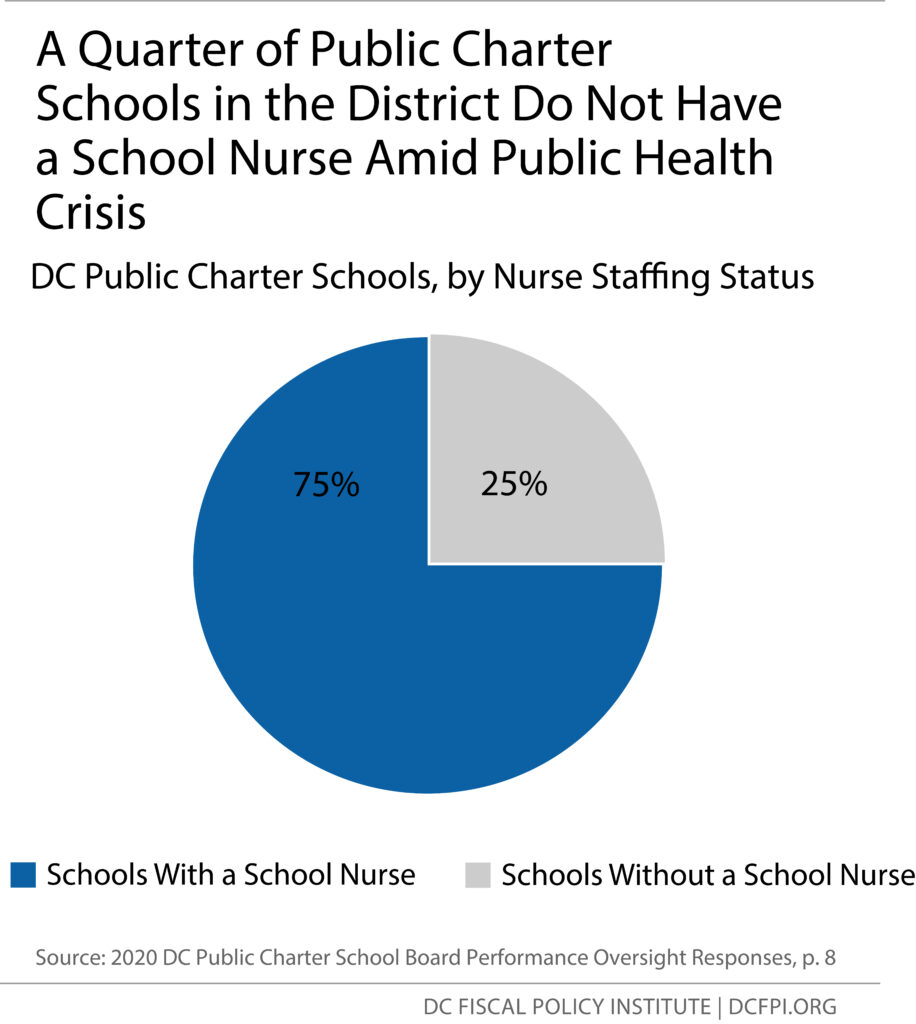

Funding for DCPS’ security contract and number of SROs has grown by 30 and 104 percent, respectively, over the last six years when adjusted for inflation.[30] Yet, the growing demand for social-emotional learning, positive school climate initiatives, and mental health supports is high while investments in these resources remains insufficient. DCPS will spend three times less in these areas in FY 2021 compared to FY 2020 and will likely underfund the number of social workers and school psychologists necessary in the new school year.

In the 2019-20 school year, DCPS had over 300 contracted security guards—a ratio of 1 security guard to 147 students—while having a social worker to student ratio of only 1-to-217 and a school psychologist to student ratio of 1-to-408 (Figure 3). That DCPS allocates social workers and psychologists based almost entirely on the needs of students with disabilities likely contributes to inadequate mental health staff to student ratios because the needs of all students are excluded from budgeting decisions.[31]

Black and brown youth in DC have long called for the end of policing and punishment-centered approaches to student safety in exchange for more holistic, student-centered approaches—such as trauma-informed professional development for school staff and greater mental health resources. The 2018 SFASA is meant to bring more of these resources inside schools, but it is not fully funded, and many schools—especially those serving high percentages of low-income students and Black and Latinx students—lack sufficient funds that are needed to help students cope with the trauma they face in and out of the classroom.

More police and security guards in schools has not made students safer and has resulted in primarily Black students and students with disabilities bearing the brunt of such practices. In DC, 92 percent of school-based arrests in the 2018-19 school year were of Black students; 31 percent were students with disabilities.[32] Studies have shown that policing in schools marks the start of the school-to-prison pipeline—the entry point to the criminal justice system—for too many kids, and fuels mass incarceration of Black and brown youth and adults.[33]

Budget Maintains Out-of-School Time Programs, Includes Small Increase for Mentoring Programs

The approved budget includes $13.6 million for the Office of Out-of-School Time (OST) Grants and Youth Outcomes, which represents a 1 percent reduction over the FY 2020 approved budget when adjusted for inflation.[34] And, it includes $284,000 in new funding that Councilmember Trayon White dedicated to OST mentoring programs that serve middle school youth who are considered at risk of academic failure.[35]

Prior to the pandemic and ensuing economic downturn, advocates were calling on District leaders to increase investments in OST by $5 million in recognition of the ongoing high-quality enrichment opportunity gaps between low-income children and their more well-off peers—more than 30,000 students were without services, despite more than 90 percent of DC parents strongly supporting OST programs.[36]

Under normal circumstances, OST opportunities—before and after school, and in summer—improve academic, social, and health outcomes, and give parents peace of mind knowing their children are in a safe environment while they work.[37] In the COVID-19 climate, OST programs are poised to continue playing a vital role in the academic and social-emotional support of students. Many students are facing increased isolation, are at increased risk of exposure to adverse childhood experiences and are losing out important instructional time. Many OST providers have quickly pivoted to connecting with students virtually and have expanded their reach by providing wrap around support to vulnerable families—such as delivering food and providing information about vital free or low-cost public resources.

It is not yet clear what OST programs will look like as social distancing continues to be the new normal. Even so, the approved budget will allow OST providers to provide safe virtual spaces for primarily low-income youth of color to connect with friends and caring adult mentors and to process the grief and emotional trauma they have and continue to experience as a result of the health pandemic. As the District’s economy recovers, policymakers should increase investments in OST programs in future fiscal years to meet demand.

[1] Eliana Golding et al.,“District Officials Project that DC Will Lose $1.5 Billion Through FY 2021,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, April 29,2020.

[2] EmpowerK12, “2019 DC PARCC Dashboard.”

[3] Doni Crawford and Qubilah Huddleston, “The Black Burden of COVID-19,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, April 16, 2020.

[4] Cheryl D. Hayes et al., “Cost of Student Achievement: Report of the DC Education Adequacy Study,” Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education, December 20, 2013.

[5] DC Code, “Supplement to foundation level funding on the basis of the count of at-risk students,” § 38–2905.01.

[6] Alyssa Noth, “More Support Urgently Needed for DC’s Excluded Workers,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, April 10, 2020.

[7] Hussein Aden et al., “COVID-19 Federal Funding Streams Available to the District of Columbia,” Office of the DC Auditor, May, 8, 2020, pp. 7-8.

[8] U.S. Department of Treasury, “Paycheck Protection Program Loans of $150,000 and above by State,”.

[9] U.S. Small Business Administration, “Paycheck Protection Program”.

[10] Will Perkins, Analysis of Paycheck Protection Program Loans received by public charter schools, Twitter, July 6, 2020.

[11] Fiscal Year 2021 to Fiscal Year 2026 Capital Improvements Plan.

[12] DC Public Schools, Empowered Learners Initiative, DC Public Schools Chancellor Ferebee and Deputy Mayor for Education Paul Kihn, Fiscal Year 2021 Budget Oversight Hearing Testimony, June 11, 2020; Committee on Education, “Report and Recommendations of the Committee on Education on the Fiscal Year 2021 Budget for Agencies Under Its Purview,” Council of the District of Columbia, June 11, 2020.

[13] Special data request to Akeem Anderson, Director of the Committee of Education at the Council of the District of Columbia, May 22, 2020.

[14] DC Public Schools Chancellor Lewis Ferebee, Email sent to DPCS families, “#ReopenStrong: Technology Tips for Learning at Home,” August 13, 2020.

[15] Mayor Muriel Bowser, Thread on her press conference about reopening public schools, Twitter, July 16, 2020.

[16] Mayor Muriel Bowser; DC Public Schools Chancellor Lewis Ferebee.

[17] Mayor Muriel Bowser.

[18] The DC Line, “Mayor Bowser, DC Education Leaders Highlight the Start of Distance Learning and Launch Digital Equity Fund,” Press Release, March 24, 2020.

[19] Connect.DC, “Building the Bridge: A Report on the State of the Digital Divide in the District of Columbia,” April 2015.

[20] Connect.DC.

[21] WJLA-TV, “30% of D.C. Students Said They Did Not Have Access to the Internet at Home,” March 24, 2020.

[22] Taylor Swaak, “A School Budget ‘That Doesn’t Recognize There’s a Pandemic’: Experts & Advocates Sound Alarm That DC Is Underfunding Key Elements for All-Virtual Learning,” The 74, August 4, 2020.

[23] DC Department of Behavioral Health, Fiscal Year 2021 Approved Budget and Financial Plan.

[24] DC Coordinating Council on School Behavioral Health, Monthly Meeting Presentation, August 17, 2020.

[25] DC Coordinating Council on School Behavioral Health, Monthly Meeting Presentation, July 27, 2020.

[26] Black Swan Academy, “Police Free Schools”; The Office of the Budget Director at the Council of the District of Columbia, “Summary of the Fiscal Year 2021 Local Budget Act of 2020,” July 7, 2020, pp. 13-14; The DC Public Schools security contract has historically been funded through an inter-agency transfer from DCPS to MPD.

[27] DC Fiscal Policy Institute, “83 Percent of D.C. Voters Support Raising Local Taxes on Wealthy Residents,” June 17, 2020.

[28] Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Fiscal Year 2021 Approved Budget and Financial Plan.

[29] Councilmember David Grosso, “Councilmember Grosso requires increased transparency in education sector and invests in expanded educational opportunities,” Press Release, May 4, 2018.

[30] DC Public Schools and the Metropolitan Police Department, Fiscal Year 2015-21 Approved Budgets and Financial Plans.

[31] Erin Roth and Will Perkins, “DC Schools Shortchange At-Risk Students,” The Office of the DC Auditor, June 26, 2019.

32] Office of the State Superintendent of Education, “2019 DC School Report Card,”2019.

[33] Jason P. Nance, “Students, Police, and the School to Prison Pipeline,” University of Florida Levin College of Law, University of Florida Law Scholarship Repository (2016).

[34] Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education, Fiscal Year 2021 Approved Budget and Financial Plan.

[35] Councilmember Trayon White, Email communication, “ Councilmember Trayon White Reduces the Exemption Level for DC Estate Tax to Fund Wrap Around Approach to Violence Impacting Youth,” July 8, 2020.

[36]All Data From: DC Alliance of Youth Advocates (DCAYA) via LIMS, Afterschool Alliance Policy State Fact Sheets, After School Alliance Time of Risk to Time of Opportunity, and LEARN 24.

[37] Afterschool Alliance, “Evaluations Backgrounder: A Summary of Formal Evaluations of Afterschool Programs’ Impact on Academics, Behavior, Safety and Family Life,” May 2011; Deborah Lowe Vandell et al., “Outcomes Linked to High-Quality Afterschool Programs: Longitudinal Findings from the Study of Promising Afterschool Programs,” Policy Studies Associates, Inc. (October 2007).