Summary:

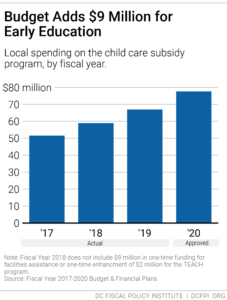

- $9.3 million increase for DC’s child care subsidy program for children in low-income families, the third consecutive year of increases.

- Funding to cover roughly half of FY 2020 goals of the multi-year “Birth-to-Three for All DC” Act.

- $4 million to expand home visiting programs, focused on immigrant families and families experiencing homelessness.

- $2.5 million to implement other parts of the Birth-to-Three Act intended to develop comprehensive supports for pregnant women and families with infants and toddlers.

- $1.4 million to make permanent a $1,000 child care tax credit adopted in FY 2019 on a one-time basis. The credit is not well targeted and unlikely to improve access to high-quality child care.

The fiscal year (FY) 2020 budget makes new investments to support early childhood development for infants and toddlers.[1] The budget includes a notable increase in funding for DC’s child care subsidy program for low-income children, building on increases in recent years, but still leaves funding well below what’s needed to support high-quality care.

The budget also provides significant resources to implement the Birth-to-Three for All DC Act (Birth-to-Three), adopted last year, which laid out a multi-year plan to provide comprehensive supports from pregnancy to age three.[2] For example, the budget expands home visiting and a program that helps pediatricians connect vulnerable families to services. Nevertheless, funding for Birth-to-Three provisions—about $16 million—is just half of what the Birth-to-Three Alliance called for in FY 2020. This is particularly important because the Birth-to-Three calls for increased future investments to achieve universal access to high-quality child care and other comprehensive supports for families with young children.

The budget makes permanent a $1,000 tax credit for child care expenses that was funded on a one-time basis in FY 2019. This tax credit is for families with incomes up to $150,000. While this program will help some families reduce their child care expenses, it is likely to be too small to enable families to obtain better quality care.

Why Early Childhood Investments Are Important

The period from birth to age three is critical for social, emotional and cognitive development—it’s the foundation on which all future learning rests. Over this time, babies’ brains grow to 85 percent of their adult size, creating more than a million neurons every second.[3] This time of growth isunmatched during any other period in life.

Good health care, strong family supports, and affordable quality early learning environments are instrumental to the well-being of young children. Yet too many children in families with low incomes and children of color face barriers to academic achievement beginning at birth. Research shows that children in low-income families “often receive early care of such poor quality that it diminishes their potential” but that investments to improve the quality of care they receive has “positive effects that can endure into the early adult years.”[4]

Birth-to-Three strengthens and expands services and provides comprehensive supports to pregnant women and families with young children. The legislation aims to improve school readiness, improve the quality of early education, offer competitive compensation for early educators, make child care more affordable to all DC families, expand home visiting, and strengthen social-emotional health and coordinated medical services for young children and families. Birth-to-Three needs additional funding over several years to phase in its provisions and make this vision a reality.

Budget Invests in Child Care, But More Is Needed to Put DC on a Path to High-Quality Care for All

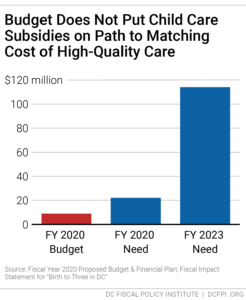

The approved DC budget includes $9.3 million in new funds to improve DC’s child care subsidy program for children in low-income families, building on increases in FY 2018 and FY 2019 (Figure 1, pg. 1). The new increase is about 40 percent of the $22 million increase needed in FY 2020, and less than 10 percent of the $114 million needed by fiscal year 2023 (Figure 2).

Access to high-quality, affordable early learning can reduce the difference in school readiness between low-income toddlers and their higher-income peers. Children who receive quality care also grow up to earn more money as adults.[5]

The District supports the education of 5,100 infants and toddlers in families with low- or moderate-incomes through the Child Care Subsidy/Voucher program, administered by the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE).[6] Families receive vouchers that they can use at licensed providers.

Yet the payments to early education providers are not enough to cover the costs of high-quality early care and education.[7] This leaves many providers struggling to make ends meet and contributes to a shortage of high-quality care. It also leaves compensation for teachers and staff at very low levels—an average of $33,000 in 2018—making it hard to attract and retain an experienced workforce.[8]

This is particularly a problem for providers in low-income neighborhoods that primarily serve children who are in the subsidy program. Nearly all licensed infant and toddler slots in Wards 7 and 8 are used by children receiving subsidies, and over half of the children in licensed child care in Wards 1, 4, and 5 are receiving subsidies.[9]

Birth-to-Three calls for raising child care subsidies by 2023 to cover the full cost of care and to raise compensation of early educators to align with salaries of public school teachers.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Tax Credit for Child Care Is Not the Best Mechanism to Improve Affordability

The budget makes permanent a $1,000 tax credit for child care expenses that was included in the FY 2019 budget on a one-time basis. The tax credit covers children up to three years old attending a licensed facility, at a cost of $1.4 million per year.

While many families struggle to manage the steep costs of early care in DC—an average annual cost of $23,000 for center-based early care in 2017—the child care tax credit is not an ideal response. At a maximum of $1,000, it offsets only a small portion of costs and thus is unlikely to affect access to quality care.

The Birth-to-Three Act includes more meaningful and targeted assistance, by ensuring that families spend no more than 10 percent of their income on early care. If funded, this provision is scheduled to be implemented after the investments in the child care subsidy program for low-income children are completed.

New Local Dollars for Home Visiting Programs to Support Families with Young Children

The budget provides $4.1 million in new funds to expand DC’s local investment in home visiting programs. This is in addition to current funding of $2.7 million in local funds and $2.9 million in federal grant funds through the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting program.

Home visiting programs support families of young children as they transition from pregnancy to parenting. Many pregnant women and young families need help understanding and supporting their child’s development and may not know how to find the resources they need to care for themselves and their children—home visiting programs can serve as a bridge to these critical resources. Currently, Department of Health home visiting programs primarily target families of children from birth to age three in Wards 5, 7, and 8 and homeless families.

Existing home visiting services do not reach all of the families who could most benefit from them, and the District’s local investment in home visiting is too low to adequately support the programs and their workforce.[10]

The Birth-to-Three Act calls for a $2 million increase for general home visiting programs —$711,000 toward this goal was funded in FY 2019 — and an $11 million increase for immigrant families and families experiencing homelessness through the Early Start program. The FY 2020 budget adds $4 million to implement the specialized programs.

Budget Funds Many Health Supports and Other Elements of Birth-to-Three Act

The Birth-to-Three Act includes several other provisions to advance healthy child development that were included in the approved budget.

Healthy Futures

Under this program, licensed professionals provide on-site mental health consultation to early childhood educators to build teachers’ capacity to reduce challenging behaviors, promote positive social emotional development, and support families. The FY 2020 budget includes $1.5 million for this program, matching the Birth-to-Three goal for this program.

HealthySteps

This evidence-based pediatric primary care program ensures the healthy development of babies and toddlers by addressing common concerns that physicians often lack time to address. This includes feeding, behavior, sleep, attachment, parental depression, and care coordination. The FY 2020 budget provides an increase of $600,000, which will allow HealthySteps to expand to two additional clinics.

Help Me Grow

The Birth-to-Three Act calls for expanding this phone-based care coordination system to help families navigate the District’s support services and maintain centralized records of developmental screenings and data. The FY 2020 budget provides $80,000 for this, well below the projected need of $4 million to implement this provision.

Lactation Certification Preparatory Program

The Birth-to-Three Act calls for new services to provide instruction, assistance, and mentorship to individuals pursuing a career in lactation consulting. The budget provides $323,000 for this.

[1]In the approved FY 2020 Budget Toolkit, DCFPI uses the most up-to-date inflation data, which is more current than the data that we used for the Proposed FY 2020 Budget Toolkit. As such, some figures may have slightly changed.

[2] For a summary, see: Marlana Wallace, “DCFPI Celebrates the Adoption of Birth-to-Three for All DC,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, July 18, 2018, https://www.dcfpi.org/all/dcfpi-celebrates-the-adoption-of-birth-to-three-for-all-dc/.

[3] “Five Numbers to Remember about Early Childhood Development,” Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2009, https://pdg.grads360.org/services/PDCService.svc/GetPDCDocumentFile?fileId=16462.

[4] “Infant-Toddler Child Care Fact Sheet,” Zero To Three, September 6, 2017, https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/2012-infant-toddler-child-care-fact-sheet.

[5] James Heckman, “Lifecycle Benefits of an Influential Early Childhood Program,” National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2016, https://heckmanequation.org/resource/research-summary-lifecycle-benefits-influential-early-childhood-program/.

[6] There were 5,124 infants and toddlers enrolled in a subsidized child care slot during Fiscal Year 2017. Office of the State Superintendent. Question 18, Fiscal Year 2018 Performance Oversight Hearing Responses, 2018. Retrieved from the Committee on Education 2018 Dropbox.

[7] See, for example: “Modeling the Cost of Child Care in the District of Columbia,” Office of the State Superintendent of Education, October 31, 2018, https://osse.dc.gov/publication/modeling-cost-child-care-district-columbia-2018. The report concludes (page 5) that “In most cases, a provider’s estimated cost of delivering early care and education services exceeded the revenue generally available to provide care at different levels of quality.”

[8] Earnings information is from May 2018 Occupational Employment Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and refers to average annual earnings for childcare workers.

[9] One hundred percent of licensed infant and toddler slots in Wards 7 and 8 and over 50 percent in Wards 1,4, and 5 are used by children receiving subsidy. Office of the State Superintendent. Question 18, Fiscal Year 2018 Performance Oversight Hearing Responses, 2018. Retrieved from the Committee on Education 2018 Dropbox.

[10] “2018 Annual Report of the District of Columbia Home Visiting Council,” DC Home Visiting Council, January 2019, https://www.dchomevisiting.org/uploads/1/1/9/0/119003017/hv_council_annual_report.pdf.