The District has a variety of programs aimed at improving health and health care access for District residents. The following agencies run these programs:

- The Department of Health Care Finance manages the District’s Medicaid and Healthcare Alliance programs. These programs provide health insurance for low income residents, and are a large reason why the District has near universal health coverage.

- The Department of Health manages public health programs like school nursing, HIV/AIDS prevention and screening, maternal and child health home visiting programs, and some nutrition programs.

- The Department of Behavioral Health funds and manages mental health and substance use disorder clinics throughout the city. The program also operates mental health programs in schools and the District’s psychiatric hospital, St. Elizabeth’s.

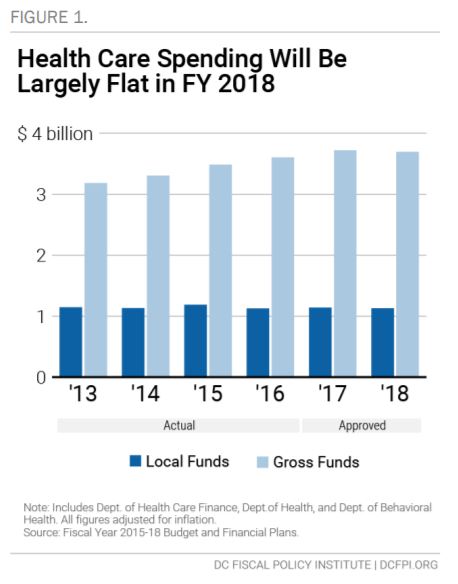

The approved fiscal year (FY) 2018 budget for these agencies totals $3.7 billion in gross funding, which includes both federal and local sources. This represents a 0.6 percent decrease, or nearly $25 million, from the FY 2017 budget after adjusting for inflation (Figure 1). General funding (which includes local funds, dedicated taxes and special purpose revenue) will fall by 1 percent, while funding from federal sources will rise just over 2 percent, largely due to an increase in federal Medicaid payments to the Department of Health Care Finance.

The District also budgets for the DC Health Benefit Exchange Authority—a fund outside of the District’s general operating budget, which is not reflected in the totals above. The Exchange operates DC Health Link, the District’s online portal for health insurance plans and financial assistance for those plans. The Exchange’s funding for FY 2018 is $28 million, a 20 percent decrease from last year, adjusted for inflation.

Little Change in Overall Medicaid Spending for FY 2018

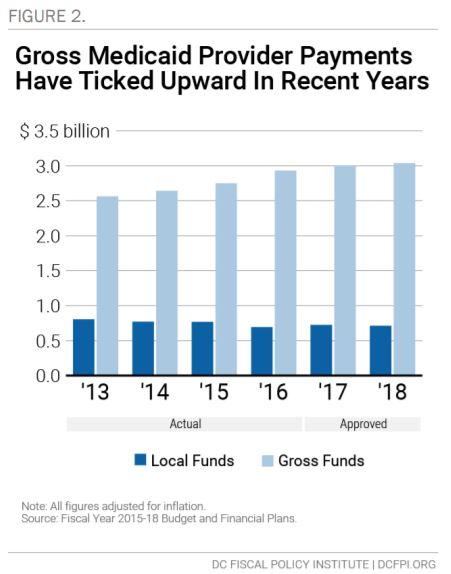

Total funding for Medicaid provider payments, including both local funds and the federal match, equals $3 billion in the FY 2018 budget, reflecting a modest growth pattern in recent years (Figure 2). Medicaid is administered by the Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF) and now accounts for 72 percent of the agency’s budget. About 242,000 residents—more than one-third of DC residents—receive health care through Medicaid.

The District’s local contribution to Medicaid will fall to $712 in FY 2018, $13 million less than FY 2017 after adjusting for inflation. At the same time, a boost in federal funding supports modest increases in overall Medicaid spending. Overall, FY 2018 budget increases for DHCF are largely the result of three drivers:

- Medicaid Provider Payments. DHCF’s FY 2018 budget calls for an increase of $31 million in federal and local sources for Medicaid provider payments, due largely to an increase of two factors: payment rates to the managed care organizations that provide health services for about three-fourths of DC’s Medicaid recipients; and an 8 percent increase in DC’s Medicaid expansion population (the group of adults under 210 percent of the federal poverty line who gained coverage as a part of DC’s implementation of the Affordable Care Act).

- DC Healthcare Alliance Payments. DHCF’s budget includes a net increase of $5.2 million due to a substantial increase in managed care rates for the DC Healthcare Alliance program (discussed in detail below).

- Hospital Provider Tax. The budget includes an increase of $14.3 million in dedicated taxes to help hospitals maintain their current federal Medicaid reimbursement rate. The tax was collected from District hospitals in FY 2016 and FY 2017, and helps maintain reimbursement rates to hospitals for in-patient services for the District’s “fee-for-service” beneficiaries. These are hospital services for Medicaid beneficiaries not in the city’s managed care program—largely elderly residents or residents with disabilities or chronic conditions. The District reimburses hospitals for 98 percent of the costs, far above the national average of 87 percent. The tax will allow the District to receive federal Medicaid matching funds of $33 million.

There is one notable decrease in health care spending for FY 2018:

- Disproportionate Share Hospital Payments. The budget includes a decrease of $14 million, due to lower projections associated with disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments. DSH payments are allotments from the federal government to qualifying hospitals that serve a large number of Medicaid and uninsured individuals. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) called for reductions in federal DSH payments from FY 2014 through FY 2020, under the assumption that increased health care coverage would reduce uncompensated care that hospitals face and thus lessen the need for DSH.[1] It’s likely that the District is receiving less in DSH payments due to the ACA requirement and the city’s low number of uninsured District residents.

Some Areas of Promise with the FY 2018 Budget for Health Coverage

- Health Reform Implementation. The FY 2018 budget devotes $2.86 million more to DHCF’s Health Care Reform and Innovation division, which identifies and shares information on new health care models and payment approaches that serve Medicaid beneficiaries. This will help the District pursue and test promising strategies to improve Medicaid costs and outcomes, and facilitate

information-sharing between health stakeholders. - PACE Program. The DHCF budget includes an additional $50,600 for the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), which provides care to Medicaid beneficiaries age 55 and older who are in need of nursing home-level care, but are not able to live in a community-based setting. This enhancement has a corresponding federal Medicaid payment increase of $39,500.

Some Concerns with the FY 2018 Budget for Health Coverage

More Than $53 Million in Managed Care Expenses Were Potentially Avoidable

The Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF) assesses the efforts of health plans to coordinate care, and has a goal of achieving high value in health care for beneficiaries. Currently, there are three health plans that serve District Medicaid and DC Healthcare Alliance beneficiaries in managed care programs. DHCF found that more than $53 million in managed care expenses, amounting to 6 percent of plan revenue, were potentially avoidable in 2016. The majority of this is driven by hospital readmissions, when a patient returns to a hospital within 30 days of a prior hospitalization. About a quarter of this is due to avoidable readmissions, wherein readmission to a hospital could have been avoided with access to primary or preventative care. A smaller share of expenses were due to visits to emergency rooms that could have been potentially avoided.[2] As DHCF continues monitoring and assessing health plan performance and pay-for-performance initiatives, it will be important to note whether future savings are realized.

No Change To Rules That Restrict Access To Health Care For Immigrants, But A Small Boost For Recertification Services

The DC Healthcare Alliance program provides health insurance coverage to low-income residents who are not eligible for Medicaid. In recent years, as Medicaid eligibility has expanded in DC under the federal Affordable Care Act, participants in the Alliance are largely immigrants who are ineligible for Medicaid under federal law, including undocumented immigrants.

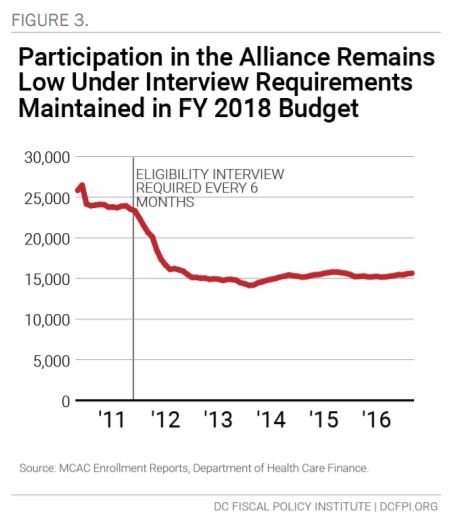

While the DC Healthcare Alliance plays a critical role in ensuring access to care for DC residents, program rules implemented in 2011 have made it hard for eligible residents to maintain their health coverage, leading to a substantial drop in participation. Despite clear indications of this problem, the FY 2018 budget takes no steps to improve access to the Alliance.

Since October 2011, the program has required participants to have a face-to-face interview every six months at a DC social service center to maintain their eligibility. This has proved to be a barrier for eligible residents trying to maintain Alliance coverage. Enrollment in the Healthcare Alliance declined sharply in 2012, and has largely remained unchanged since then (Figure 3).[3] During the first year of the policy from October 2011 to October 2012, the number of DC residents in the Alliance dropped by one-third, from 24,000 to 16,000. Enrollment has fallen and risen modestly since then, but currently stands around 15,600.[4]

The intent of the six-month recertification was to discourage ineligible people from applying for the Alliance, but evidence among legal service provider cases and data analysis by the Department of Health Care Finance suggests that it is creating a barrier for eligible enrollees to maintain coverage under the program. In 2016, nearly half of all Alliance enrollees had left the program after 12 months.[5]

The six-month recertification requirement also creates problems for other residents seeking public benefits. Alliance applicants represent a

large share of residents at DC’s five social service intake centers each day, and their applications take longer than the average visit to these centers. The Alliance recertification rules thus contribute to long lines and wait times—and to clerical errors such as lost paperwork—at the social service centers. Data collected in 2015 suggest that Alliance recipients make up one-fourth of service center traffic in a given month, even though they represent a very small portion of service center clients,[6] and less than 10 percent of individuals covered under DC’s health insurance programs.[7] Wait times for Alliance recipients seeking to recertify at service centers are longer than wait times for Medicaid recipients [8]— reflecting the language and case management needs of the Alliance population.

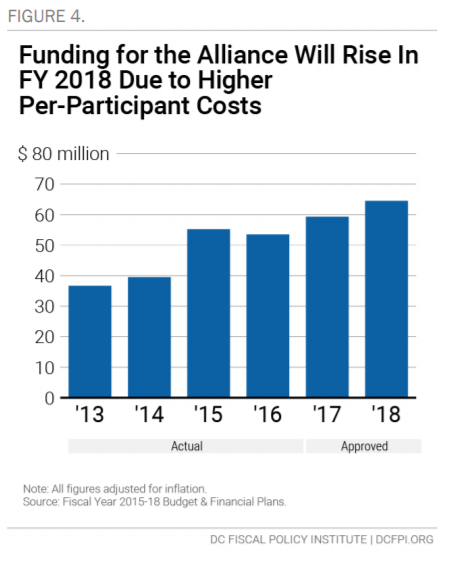

Funding for the DC Healthcare Alliance in FY 2018 is nearly $65 million, a 9 percent increase from last year adjusted for inflation (Figure 4). The increase does not reflect an anticipated increase in enrollment, or notable changes in how the program is delivered. Instead it merely reflects an increase in per-participant costs, following on a substantial increase in FY 2017. This suggests that the Alliance membership includes residents with serious health problems, and it may reflect that barriers to participation in the Alliance keep residents away until their health problems become serious.

Recent attention on the program may help highlight its barriers and encourage policy changes to the eligibility process. The Department of Health Care Finance is currently analyzing the Alliance program to better understand program costs and enrollment trends. Furthermore, two pieces of legislation recently introduced in the DC Council would allow Alliance beneficiaries to recertify over the phone, and one of the bills would expand the recertification period back to 12 months. Both of these bills hold promise of eliminating barriers to accessing health care coverage through the Alliance.

In response to the administrative hurdles that eligible beneficiaries face, the FY 2018 budget includes about $280,000 in the Department of

Human Services’ budget for additional staffing to provide Alliance recertification services. This includes three full-time staff positions; two additional out-station field workers that will provide enrollment services at the request of community organizations, and one supervisor.

Some Public Health Programs Will Be Cut in FY 2018, and Others Will See Increases

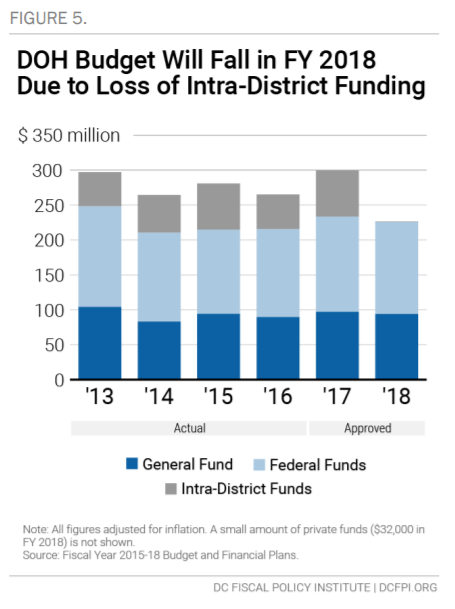

The FY 2018 budget for the Department of Health (DOH) is $231 million, a $68 million decrease from FY 2017 after adjusting for inflation (Figure 5). However, this figure does not reflect a reduction in services. Most of the decrease stems from a discontinuation of DC’s methods to do bulk purchasing of pharmaceuticals through the DC Pharmacy Warehouse. The Pharmacy Warehouse is a licensed drug distribution center that administers the drug component of the Department of Health, the Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF) and other DC programs that require prescription medications as a part of their protocol, including DC AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) and DC Healthcare Alliance program clients. For FY 2018, both DHCF and DOH will incorporate a new business model for the pharmaceuticals program, with no negative impact to the public.

Excluding this change and focusing on general and federal funds, which make up the vast majority of the DOH budget, the change to the FY 2018 budget for the Department of Health is much smaller, representing a 3.3 percent decrease, or $7.7 million below the FY 2017 budget after adjusting for inflation.

There are changes to a number of public health services, including both expansions and cuts.

- School Based Health Centers and Disease Prevention. The FY 2018 budget for DOH includes a net reduction of $2.2 million mainly in sub-grants that supported School Based Health Centers, and in preventive services at the HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STD, and TB Administration division.

- Tobacco Prevention Law. The FY 2018 budget for DOH does not include $674,000 in funding needed to implement recently enacted legislation from the DC Council, which increases the smoking age to 21 in the District. The law would help reduce tobacco use by DC’s youth over time.

- Emergency Response. The budget reflects an increase of $480,000 from federal grant funds to the Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Administration, which will help with Ebola treatment centers and infection control.

- Substance Use Disorder. For FY 2018, the budget for DOH includes an enhancement of $850,000 to expand substance abuse treatment for opioids and reduce the number of active opioid users in the District, as well as overdoses and overdose fatalities.

- Joyful Food Markets. The FY 2018 budget provides $1 million for the Joyful Food Markets, a slight drop from FY 2017 funding of $1.1 million. Joyful Food Markets are monthly pop-up grocery stores operating in Wards 7 and 8 elementary schools.

- Food Security. The FY 2018 budget includes $300,000 in new funding to support community-based in-home meal delivery services for individuals with significant health challenges such as cancer, HIV/AIDS, and other chronic conditions.

- Pregnancy Prevention. The budget adds $625,000 in one-time funding to support Teen Pregnancy prevention programs and initiatives at the Crittenton Hospital, a modest increase from one-time funding of $500,000 in FY 2017. It also includes $41,000 to continue funding teen peer sexual health educators.

Health Care Access

The FY 2018 budget includes several initiatives to boost access to health services:

- East End Medical Center. The budget dedicates $300 million for a new Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF) capital project to build an integrated health system east of the Anacostia River, in an effort to improve health care access and reduce disparities in health status. Access to primary care physicians, specialists, and community health centers is more limited east of the Anacostia River than in the rest of the District. The project includes the construction of a new East End Medical Center on the Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital campus, an urgent care center, and an ambulatory care center.

- Telehealth. To help further health care delivery innovation and combat the rising opioid addiction crisis, the FY 2018 budget sets aside $600,000 in grant awards for telehealth interventions and targeted medical treatments for District residents suffering from

opioid addiction. DHCF will administer the grants. Four grants will go to promote telehealth in Wards 7; two will bring telehealth

services to a homeless shelter or public housing project; and one will go to a college of pharmacy to help health care providers use precision medicine to patients with opioid use disorder. - Provider Recruitment and Retention. The FY 2018 budget includes just over $100,000 to the District of Columbia Health Professional Recruitment Fund, which will help physicians, dentists, and other health professionals in the District repay their educational loans. These funds will give preference to providers who show a commitment to serving in areas with a lack of health care professionals or that are medically underserved.

Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Services

The FY 2018 budget for the Department of Behavioral Health (DBH) is $272 million, a $1.5 million decrease from last year after adjusting for inflation. It is funded primarily through local funds. Federal matching funds for mental health and substance use disorder services are included in DHCF’s budget, while local matching funds are included within the DBH’s budget.

Mental Health Rehabilitative Services (MHRS) spending overall—including federal funds— will increase $2.8 million in the FY 2018 budget due to a 2.3 percent Medicaid growth rate projected by the Department of Health Care Finance, based on the cost of health care services in the District. The FY 2018 budget includes an additional $2.9 million in local funding to the DBH budget for MHRS and Adult Substance Abuse Rehabilitative Services (ASARS) provider rates. MHRS and ASARS providers offer critical behavioral health and substance abuse services that are not covered by Medicaid, such as vocational supportive employment.

For FY 2018, DBH will undergo a major restructuring, as some divisions are eliminated, and some new and existing activities are added to new divisions. The stated goal of the realignment is to improve access and accountability, increase efficiency and effectiveness, create clarity among service areas, and reduce silos.

Other changes to DBH’s budget in FY 2018:

- Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program. An increase of $1.6 million will go primarily toward the Comprehensive

Psychiatric Emergency Program (CPEP) and forensics studies. CPEP is a twenty-four hour, seven day a week operation that provides emergency psychiatric services, mobile crisis services, and extended observation beds for individuals 18 years of age and older. - Returning Citizens. DBH, along with several other agencies will share $1.2 million to create a Returning Citizens Portal of Entry that will coordinate services to District residents returning from incarceration.

- St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. St. Elizabeth’s, the state psychiatric hospital for the District, will see a net increase of $3.9 million, primarily due to union collective bargaining agreements and right-sizing of overtime hours. This does not reflect an increase in services, however.

- NEAR Act. The FY 2018 budget includes $970,000 to support the Community Crime Prevention Team’s implementation of the

Neighborhood Engagement Achieves Results (NEAR) Act, an arrest diversion program intended to reduce repeat arrests among underserved populations and provide alternatives to incarceration. - Wayne Place. The FY 2018 budget includes an additional $844,000 for Wayne Place, a transitional home for young adults who need support to live independently and succeed.

- Level of Care Utilization. A local funds reduction of $826,600 is anticipated through scope of coverage reviews for individuals with a particular Level of Care Utilization System (LOCUS) score.

Funding for the DC Health Benefit Exchange Authority Reflects Programmatic Savings While Maintaining Access to Critical Services

FY 2018 budget includes $28 million for the DC Health Benefit Exchange Authority (Exchange), which operates DC Health Link. DC Health Link is the District’s online portal for Medicaid, private health insurance plans and financial assistance for those plans. This budget is a 20 percent decrease from FY 2017 after adjusting for inflation, largely reflecting multiple realized programmatic cost savings after prior investments in technical infrastructure. Even with the reduction, this budget maintains the funding needed for the agency’s operations for DC Health Link.

The Exchange generates funds through a broadbased assessment on health insurance plans operating in the District. The largest shares of its budget are devoted to information technology (IT) operations, assistance to help consumers access insurance and benefits through the Exchange.

Since it first opened, DC Health Link has served nearly 312,000 individuals, including 43,177 DC residents enrolled in private coverage, 80,552 enrolled through the small business marketplace (SHOP), and 187,894 residents who have been found eligible for Medicaid. Although some marketplaces across the country had expensive starts due to the large costs involved up front for technology and consumer assistance, DC Health Link has been able to reap the benefits of its investments, including a first-of-its-kind state partnership with Massachusetts where it will be providing the technology and operational support for their SHOP marketplace, and being recently recognized as the top exchange marketplace in the country for its consumer comparison shopping tools.

[1] Kaiser Family Foundation, “How Do Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Payments Change Under the ACA?” November 2013.

[2] District of Columbia Primary Care Association and District of Columbia Hospital Association, Public Health & Finance Budget Briefing, April 13 2017.

[3] Medicaid expansion through the ACA in 2010 shifted 32,000 residents from the Alliance program to Medicaid. However, after a period of stable enrollment, caseloads began to decrease after a six-month, in-person recertification requirement began for all enrollees in FY 2012.

[4] Department of Health Care Finance, Monthly Enrollment Report, June 2017.

[5] District of Columbia Primary Care Association and District of Columbia Hospital Association, Public Health & Finance Budget Briefing, April 13 2017.

[6] Wes Rivers, DC Fiscal Policy Institute; Chelsea Sharon, Legal Aid Society of the District of Columbia, “Testimony for Public Oversight Hearing on the Performance of the Economic Security Administration of the Department of Human Services,” “District of Columbia Council Committee on Health and Human Services, March 12, 2015.

[7] Department of Health Care Finance, Monthly Enrollment Report, January 2017.

[8] Ibid.