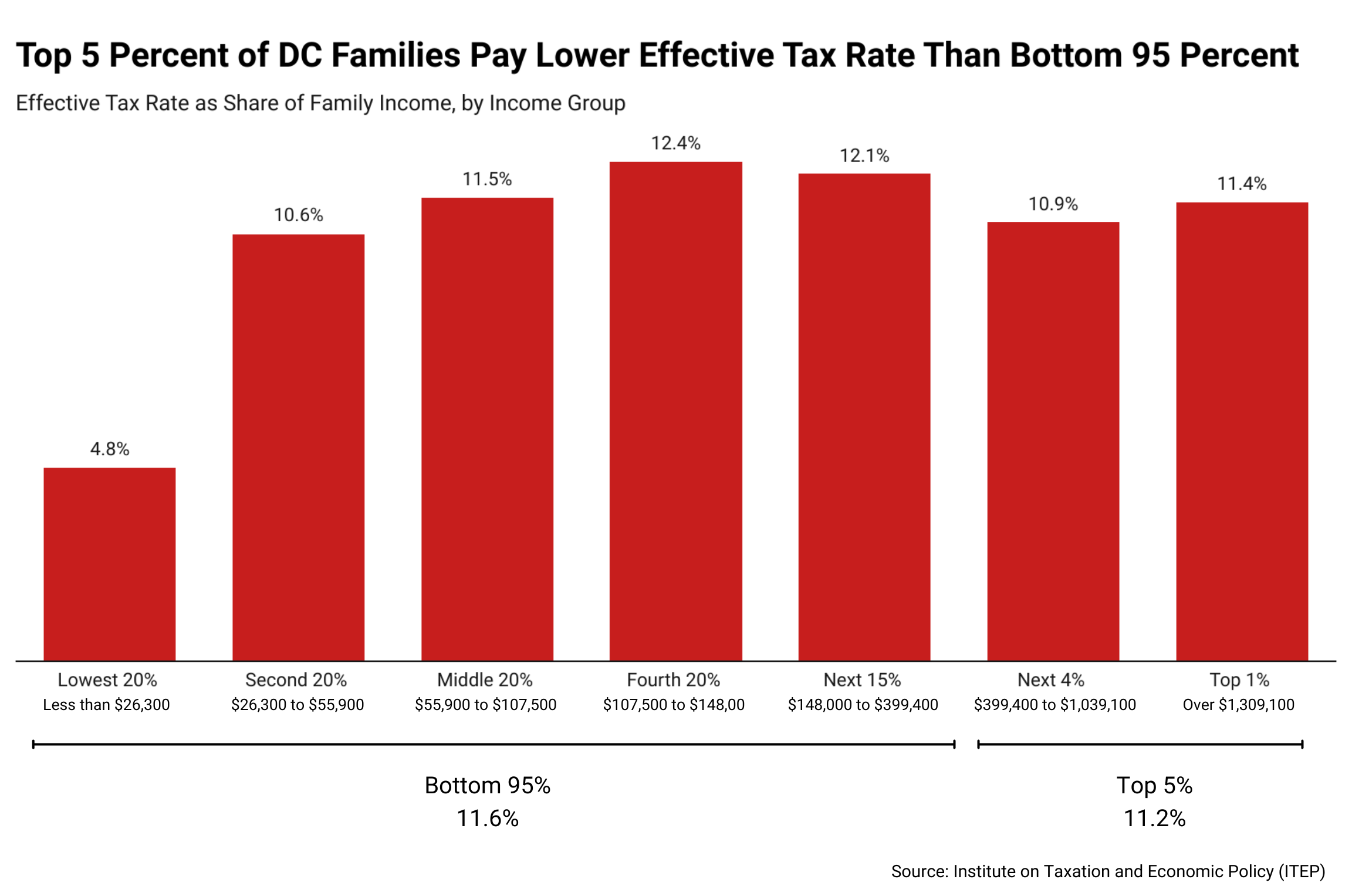

The top 5 percent of DC families pay a lower share of their income in taxes than the bottom 95 percent combined, according to the latest edition of Who Pays?, a report by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP). While ITEP notes that DC tilts slightly progressive and ranks as least regressive when compared to other states, DC’s tax code still protects and grows income and wealth concentration among a small share of families. For example, in the District, an executive with an income over $1.1 million pays on average a smaller share of their income in taxes than a middle-class family with two teachers earning $60,000.

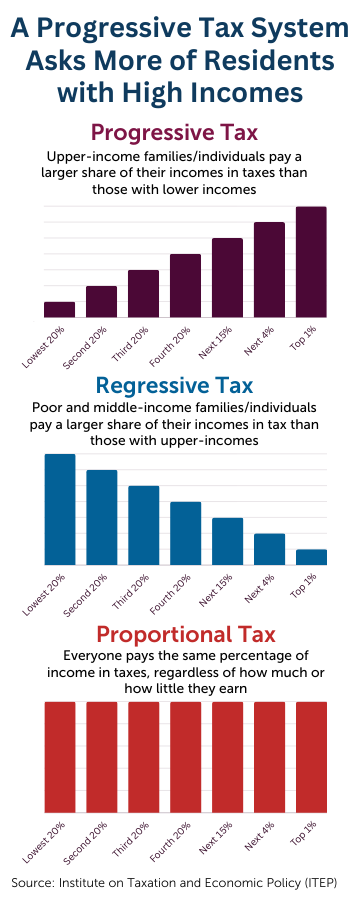

Tax advantages for residents at the top privilege white residents—who account for the vast majority of DC’s richest residents—and serve to concentrate their wealth. This comes at the expense of public investments in underserved communities that advance racial justice. To advance racial equity, DC lawmakers should adopt changes to the tax code to help ensure effective tax rates—all taxes paid as a share of income—rise steadily across the income scale (Figure 1).

DC Has Made Progress Towards Tax Justice but Still Favors the Top 5 Percent

The relative progressivity in DC’s tax code is driven in part by a large expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and modest income tax increase on residents with annual taxable incomes above $250,000 adopted in 2021 through the Homes and Hearts Amendment to the budget, as well as other progressive changes over time. The scheduled increase in DC’s EITC for workers with children, which is set to rise from 70 to 100 percent of the federal credit between 2024 and 2026, will make the District’s tax code more progressive by dropping the effective tax rate for the lowest-income 20 percent of residents by 2 percentage points and the second lowest-income 20 percent by 0.4 percentage points.

While the District has taken important steps to reduce the taxes paid by households with the very lowest incomes, more work is needed to shift taxes paid by moderate- and lower-middle income families to residents who’ve benefitted the most in DC’s economy. This can help correct injustices in the tax code that continue to exacerbate racial and economic inequity. DC still taxes the top 1 percent less than the third and fourth income quintiles as well as the following 15 percent. In addition, the top 5 percent of DC families pay a lower effective tax rate (11.2 percent) than the bottom 95 percent (11.6 percent) (Figure 2).

To fix this imbalance, DC lawmakers should

- Institute a local Child Tax Credit to build on the District’s efforts to increase basic income and significantly reduce child poverty, especially among Black children.

- Expand the property tax circuit breaker, also known as Schedule H, to reduce property taxes for households with low or moderate incomes when they become too high relative to household income. Right now, the maximum credit limits how much property owners with low incomes can benefit. By getting rid of the cap on the credit, DC could ensure that the amount actually increases with need.

- Raise taxes on multi-million-dollar homes. DC’s single-rate property tax imposes the same rate on $300,000 homes as it does on multi-million-dollar homes. By taxing residential property more progressively, DC could help correct the racist harm of past policies that promoted white homeownership and wealth building at the direct expense of Black and non-Black people of color.

- Eliminate tax preferences and loopholes that protect and further concentrate wealth. The special tax treatment of capital gains income—which overwhelmingly flow to the top 1 percent—is part of why the top 1 percent of DC taxpayers, on average, have a lower effective tax rate than those in the middle of the income scale.

Does DC Compare to Other States?

The District is a unique jurisdiction that compares to state and major cities in some ways and diverges in others. In this case, DC largely has the taxing authority of both a state and a city, levying income, sales, property, and other taxes to fund essential services that support a robust economy. At the same time, DC faces important challenges that make it different from other states. For example, Congress has limited our ability to tax the income of non-residents as other states do as a matter of course, costing the District an estimated $3 billion each year. This means we ask more of residents in terms of taxes than we might otherwise.

DC also is different from other cities in that it has the spending responsibilities of a city, as well as that of a county and state, which means it funds many more services. And, in ITEP’s analysis, the taxes levied by major cities in other states get averaged across the full state population, diluting the tax contributions in major population centers, skewing comparisons. Furthermore, DC prides itself in its commitment to progressive policies. Our collective resources provide public services that are not widely available in most other states or cities, such as universal pre-k for three- and four-year-olds, higher pay for private sector child care educators, paid family leave, and significant investments in housing.

Does This Report Compare to Past Reports?

There are methodological differences since the last iteration of Who Pays? that make the new analysis incomparable to past analyses (see Appendix G in the report). For example, this analysis includes:

- State and local tax laws that have changed since September 10, 2018.

- Economic and social changes that have shifted the underlying distribution of income used as the measuring stick for tax incidence.

- Updated economic and demographic data from 2023 (the previous version used 2015 data as its baseline).

- A range of minor taxes that were excluded from previous editions like taxes on insurance premiums, natural resource extraction, and real estate transfers, which means the analysis now covers 99.7 percent of all state and local tax revenues (previously it was 90 percent).

- New data sources, new methods for integrating data, and some modifications in modeling approach based on advancements in methodological research that improve the analysis of areas like business activity, corporate apportionment rules, and estate taxes.