The District of Columbia is home to the nation’s capital, nearly 700,000 residents, and a robust economy that benefits the broader metropolitan area. But despite holding the same responsibilities as other Americans – including paying federal income taxes – DC residents are denied their full rights, including voting representation in Congress.

Black and brown people make up the majority of DC’s population, making statehood a racial justice issue. Putting a stop to Black communities’ increasing political engagement was the driving intention behind voter suppression in the period following Reconstruction, and that legacy continues today. While DC has no votes in Congress, elected officials from the 50 states have the power to interfere in local laws, with significant consequences on the health, safety, and well-being of District residents.

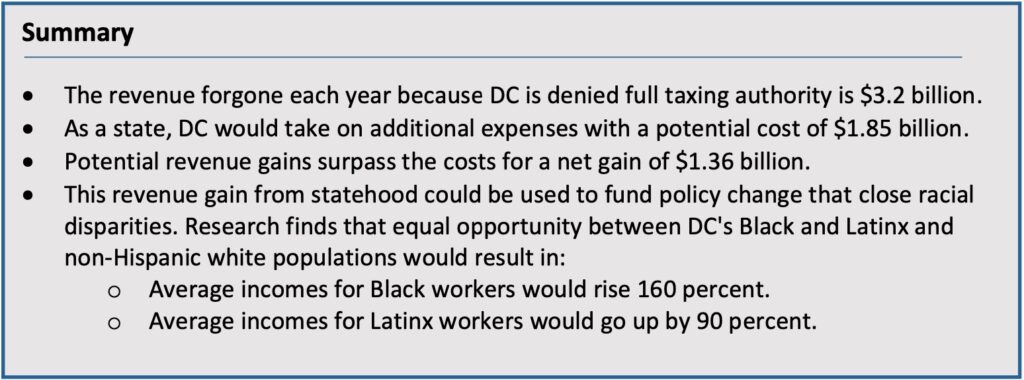

Denying DC statehood also has extensive fiscal consequences. The revenue forgone each year because DC is denied full taxing authority is $3.2 billion, according to DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI) analysis. That $3.2 billion equates to nearly one-fifth of DC’s Gross Fund spending for fiscal year (FY) 2021, is more than three-fifths of what the District spent on Human Support Services, and it is slightly more than the District’s investment in schools that year.[1] And, even though DC would take on additional and substantial expenses as a state, the potential revenue gains surpass the costs. With this increase in resources, District leaders could invest in transformative policy changes that advance racial justice and strengthen DC’s economy.

DC residents have been calling for the return of their full democratic rights for more than 200 years. Momentum for statehood is only growing. DC residents themselves made clear their desire for statehood, with 86 percent voting in favor in a 2016 referendum.[2] Mayor Muriel Bowser and Non-Voting Representative Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC) have repeatedly called for DC statehood. In 2020 and again in 2021, the House of Representatives passed a bill to make DC a state. This marked the first and second time in history a body of Congress advanced such legislation. The US Senate failed to take up the measure each time.

By recognizing DC residents’ rights to self-governance and federal voting representation, Congress would be correcting a historic harm that is rooted in anti-Blackness and perpetuates racial inequality. With fewer restrictions and the potential revenue that statehood offers, DC could take greater steps to minimize economic struggle, end displacement, house residents, guarantee jobs and income, and advance reparative policy in our most neglected communities. In doing so we would create a stronger, equitable economy for the future.

Racist Roots of District Disenfranchisement and Limited Self-Governance

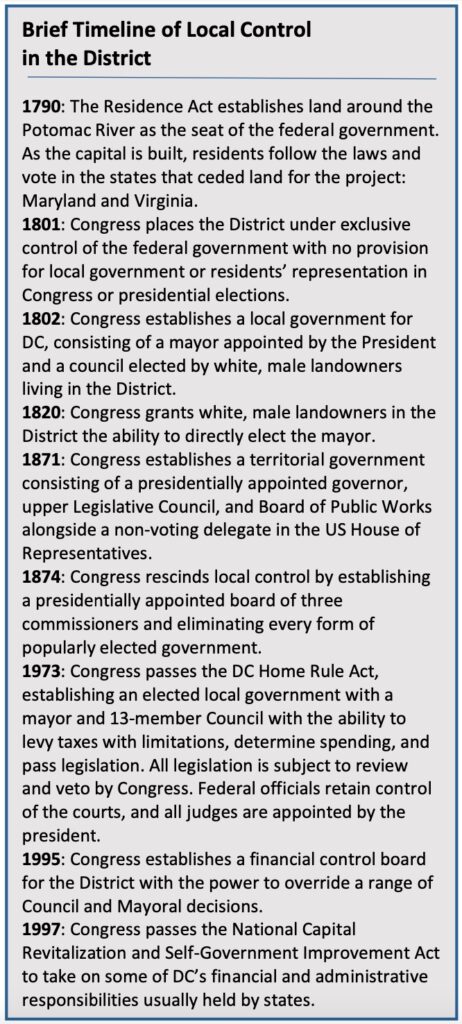

White supremacy and the orchestrated efforts to suppress Black political and economic power have played a driving role in the disenfranchisement of DC residents. After a brief period in which Black men could vote and Black communities became increasingly politically active, all DC residents—Black and white—lost all voting rights in 1874.[3] Following Reconstruction, states across the South made moves to secure white political and economic dominance with lasting impacts on the power and resources available to communities of color.[4]

White supremacy and the orchestrated efforts to suppress Black political and economic power have played a driving role in the disenfranchisement of DC residents. After a brief period in which Black men could vote and Black communities became increasingly politically active, all DC residents—Black and white—lost all voting rights in 1874.[3] Following Reconstruction, states across the South made moves to secure white political and economic dominance with lasting impacts on the power and resources available to communities of color.[4]

DC was the first majority Black major city in the US and had a reputation as a haven for Black opportunity even during slavery. At the beginning of the 19th century, Washington City had 400 free Black people—nearly double the number of eligible voters, or landowning white men. Within the first decade, that number had nearly quadrupled, and free Black people were more than 30 percent of the Black population. By 1830, most of DC’s Black residents were free and despite the white-led government denying them the same employment opportunities and freedoms of their white counterparts, they secured jobs, established community organizations, and bought property.[5]

During Reconstruction, Congress used its exclusive authority over DC to “field test” policies, from freedman’s relief to public education for Black children, before implementing them across the South. In 1867, Congress passed a law over President Andrew Johnson’s veto that allowed Black men to vote in the District’s municipal elections. Black Washingtonians voted in high numbers and by 1869, Black men had been elected to positions in every ward. The District’s biracial local government succeeded in providing jobs to a growing Black middle class, supporting the expansion of the Black public school system, and passing anti-discrimination legislation.[6]

To Suppress Black Political and Economic Power, a Movement to End Democratic Governance Takes Form

Black prosperity repeatedly triggered backlash. The city passed its first Black Code in 1808 to restrict the relative freedom of the free Black community by instituting curfew, prohibiting assembly, and requiring evidence of Black freedom. Over time, Black codes became increasingly restrictive to limit economic opportunity and discourage Black migration to DC.[7]

A movement to consolidate the District under unelected presidential appointees began in direct response to Black Washingtonians exercising their right to vote. Advocates framed undemocratic rule as an efficient method to end the high taxes and spending that came with increased Black political power. In 1871, Congress created a single territorial government for a consolidated District of Columbia that greatly limited residents’ electoral power.[8]

In 1874, Congress rescinded that limited local control and DC residents of all races lost all their voting rights. An 1878 Washington Post editorial plainly stated the racist beliefs around this change to rule-by-commissioners: “The present form of alien government is about as bad as to be devised, but a system which gives the control of the District to ignorant and depraved negroes, is still worse.”[9] “An experiment had been tried in negro suffrage and it had failed,” said an academic study in 1893.[10]

The commissioners who ran the city were all white men until 1961.[11] Losing the right to vote hurt both Black and white voters, but it was devastating for Black Washingtonians who struggled to advocate for their interests and hold the commissioners accountable under this non-representative form of government.

DC Suppression Part of a Broader Effort to Cement White Political and Economic Dominance

States across the South similarly pushed successful efforts to end biracial Reconstruction governance, disenfranchise Black voters, and restore a racial hierarchy with severe economic consequences. In 1890, Mississippi disenfranchised nearly all the state’s Black voters and enacted a supermajority requirement for all state tax increases, making it next to impossible to meaningfully raise property taxes and secure public investments in education, health care, and other public goods that would support Black people excluded from full participation in the economy. In Alabama, legislators overturned the state constitution written by a biracial group of delegates during Reconstruction to install highly restrictive caps on property tax rates and limit the amount white landowners would have to contribute for the benefit of the majority Black population that did not own property. These and other similar efforts that were paired with violence and voter suppression effectively pre-empted future efforts of multi-racial coalitions working to resource collective needs.[12]

This practice of racist pre-emption continues today as states obstruct policies that would disproportionately benefit Black people and other people of color. When Birmingham City Council voted to raise the city’s minimum wage to $10.10 per hour in 2016, the state blocked the ordinance and brought the wage back down to $7.25.[13] Nearly 70 percent of Birmingham’s residents are Black.[14] The state of Texas sought an injunction against Austin when the city passed laws requiring businesses to provide their employees with paid sick leave.[15] In Austin, Hispanic and Black workers are less likely to have paid sick time than workers in any other racial or ethnic group.[16]

Home Rule Was Critical Step Forward but Not Full Autonomy or Representation

Nearly 100 years after Congress stripped District residents of their right to vote for local representation, Congress passed the Home Rule Act in 1973. The law provided residents with the right to vote for a city council, mayor, and advisory neighborhood commissioners.[17] Today, DC residents can work through a democratically elected government to shape local decisions around raising revenue, spending priorities, and other legislation affecting their daily lives. This is the highest level of self-government the District has had since it became the seat of the federal government, and yet it does not offer full autonomy or representation.

DC residents, for example, still do not have voting representation in Congress to advance District priorities or to shape federal policy that affects the nation as a whole. And Congress reviews all legislation passed by the Council before it can become law and retains authority over DC’s budget. While the District has largely been able to operate with autonomy, there have been important exceptions. For example, the federal government imposed upon the District a Control Board in the mid-1990s (see discussion below) and DC has at times been subject to federal pre-emption as other cities are by states, with social, health, and economic consequences for DC residents. For example, each year Congress prohibits DC from spending local funds to provide insurance coverage for abortion care through Medicaid. The disproportionate number of people of color who are enrolled in Medicaid often struggle to make ends meet and denying them access to abortion care further perpetuates economic insecurity. In 1998, Congress banned DC from using local tax dollars to fund needle exchange programs, which are shown to reduce the spread of HIV/AIDs, before reversing the ban in 2007.[18] In 2015, Congress passed a budget provision to undermine the results of a District referendum approving the legalization and regulation of cannabis, criminalization of which has had extremely disproportionate negative consequences for Black and brown residents.[19] Today, several members of Congress are taking aim at DC’s move to enfranchise people without US citizenship in local elections and to revise its criminal code.[20]

If made a state, DC would have the highest proportion of Black residents of any state[21] and help correct the underrepresentation of voters of color in the American political system.[22] By recognizing DC residents’ rights to self-governance and federal voting representation, Congress would be correcting a historic harm that is rooted in anti-Blackness and perpetuates racial inequality.

Fiscal Implications of Statehood

Statehood would bring a full array of benefits to the District, most importantly the voting rights, civic responsibilities, and political representation promised to citizens of the United States but currently denied to DC residents. It would give the District full control over budget and legislative decisions—and more time to make those decisions—by eliminating congressional review and allowing the District to adopt a fiscal year that aligns with the needs of DC’s schools and the University of DC.

Statehood also would have important fiscal implications. The District would be newly responsible for several areas of spending that are currently funded by the federal government in recognition of DC’s unique status. But statehood also could result in the generation of billions in new revenue to afford the District greater public investment in its neighborhoods and communities, particularly where Black, brown, immigrant, and low-paid residents have been sidelined by racism and economic exclusion. And statehood would expand our income tax base and likely make our tax system more equitable.

With Increased Tax Collections, DC Could See Over $3 Billion More in Annual Revenue

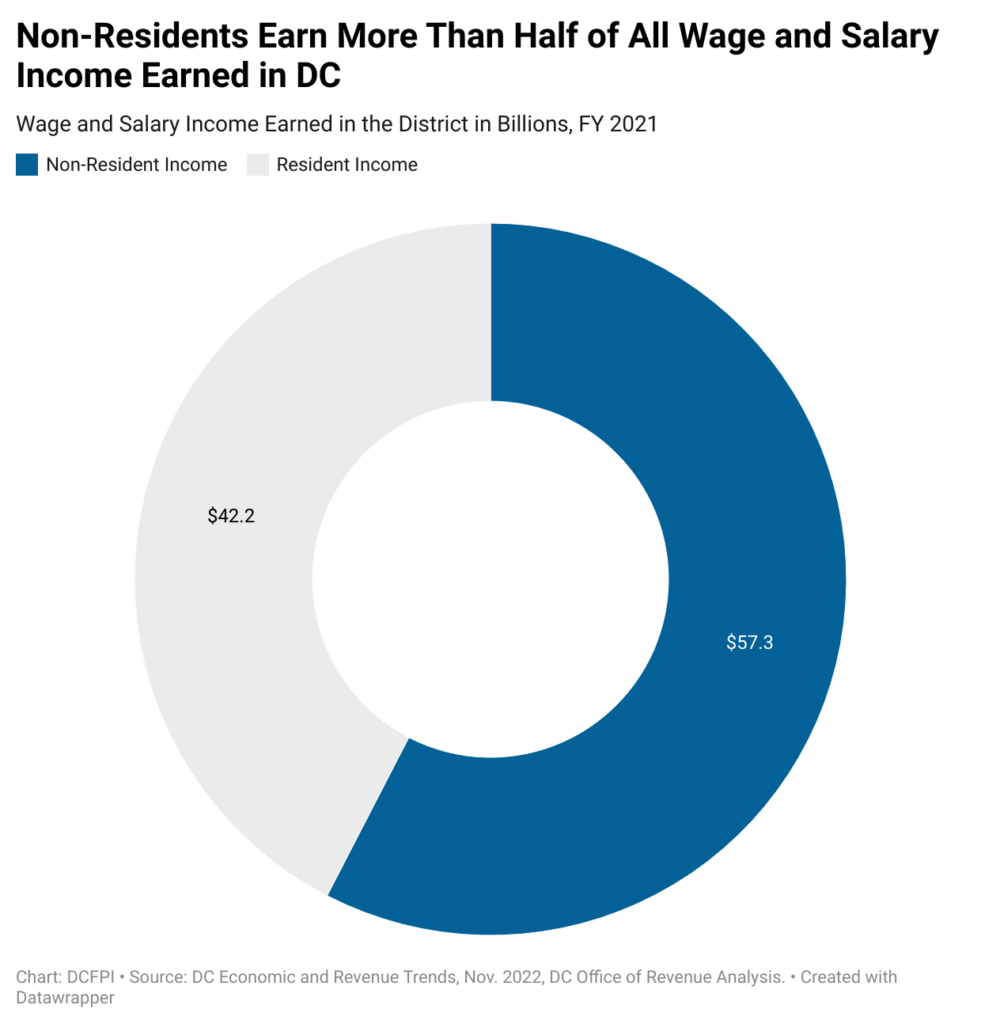

In addition to the denial of voting rights and representation, the District is also denied the full taxing authority of a state. Since the adoption of Home Rule in 1973, DC has held the multi-layered responsibilities of ensuring the administration of public services that normally would be distributed across city, county, and state governments. However, as a federal district, DC is not allowed to tax wage and salary income earned in the District by people living outside of its boundaries (non-residents)—an authority held by all states with income taxes and exercised by many.[23]

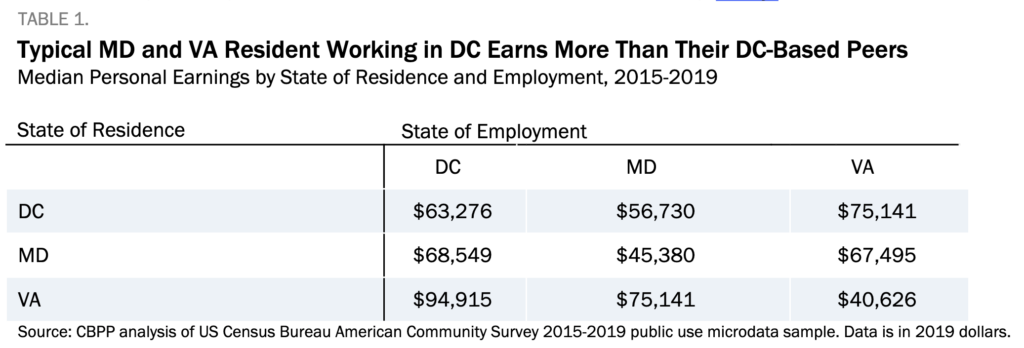

According to US Census data, about 226,000 residents of Virginia and 320,000 residents of Maryland earn income in DC, where they enjoy the vibrancy of DC’s economy, industry, and many public services and workers’ rights such as paid leave benefits.[24] While the District currently has “reciprocity” with the two states—meaning that Maryland and Virginia also do not tax income earned by DC residents within their borders—far fewer DC residents work and earn their living in those states, and the dollars they earn are a small fraction of the total income earned in those states.[25]

In addition, the typical non-resident from Maryland or Virginia working in DC is better paid than the typical worker in those states, according to US Census data (Table 1, pg 6). The median personal earnings of Marylanders and Virginians working in DC is both higher than the median earnings of the residents of the two states and the earnings of residents of DC. The right to tax all DC-earned income would broaden the District’s tax base to about 560,000 additional earners whose relatively greater level of prosperity is made possible by DC’s strong local economy and the local tax dollars that support it.

The revenue forgone each year because Congress denies DC full taxing authority of non-resident wages and salaries earned in the District is striking—nearly $3.2 billion annually.[26] (There is an additional significant revenue loss because court decisions have barred the District from applying the Unincorporated Business Tax to the profits of businesses like law, accounting, lobbying, and consulting firms whose earnings come from professional services.[27]) Non-resident wage and salary income was $57.3 billion in fiscal year 2021, or 58 percent of all income earned in DC, compared with $42.2 billion earned by residents (Figure 1). To estimate forgone revenue, DCFPI applied an estimated effective income tax rate[28] to the wage and salary income of non-residents. The fact that the median earnings of non-DC residents is higher than the earnings of DC residents suggests that the revenue gains of taxing non-resident income could be even greater than the estimates shown here.

That $3.2 billion equates to nearly one-fifth of DC’s Gross Fund spending for FY 2021, is more than three-fifths of what the District spent on Human Support Services, and is slightly more than the District’s investment in schools that year.

Revenue Gains Likely Surpass New Expenses

As a state, DC would likely resume responsibility for the cost of several public services that other states finance directly, such as the court system. DC previously funded these services with District revenue between the 1973 Home Rule Act and the 1997 National Capital Revitalization and Self-Government Improvement Act.[29] With Home Rule, the District took on many expenditures of a state without the full, corresponding taxing authority. The federal government partially offset new expenses with annual lump-sum payments that started off woefully inadequate and further declined in value over time. Though created in large part by continued federal limitations on revenue, DC developed a budget deficit and saw its financial health decline, leading the Clinton administration and Congress to appoint the DC Financial Responsibility and Management Assistance Authority, otherwise known as the Control Board, in 1995. The Control Board had the ability to override Council and Mayoral decisions and the authority to take a wide range of actions to bring the budget into balance.

Under the Revitalization Act, the federal government followed the recommendations of the Control Board to relieve the District of some of its financial obligations given its unique status and revenue limitations, most notably the massive, unfunded pension liability it had transferred to the District, a greater share of DC’s Medicaid costs, and the costs of DC’s court system, adult felony prison population, probation and parole, and other criminal justice system expenses.

In 1999, the federal government also provided DC residents with the DC Tuition Assistance Grant (DC TAG) Program, which Congress created to offer DC’s college-bound recent high school graduates “in-state tuition” at state colleges and universities outside of the District and grants for attendance at private colleges in the region. (While statehood could shift the costs of this program to DC, it’s also possible that this along with other substantial investments could be “earmarked” for DC if residents had voting representation in Congress.)[30] Even with this federal support, the District continued to fund an array of services that are typically paid for, or at the least supplemented, by a state-level government, such as schools, public benefit programs, and infrastructure.

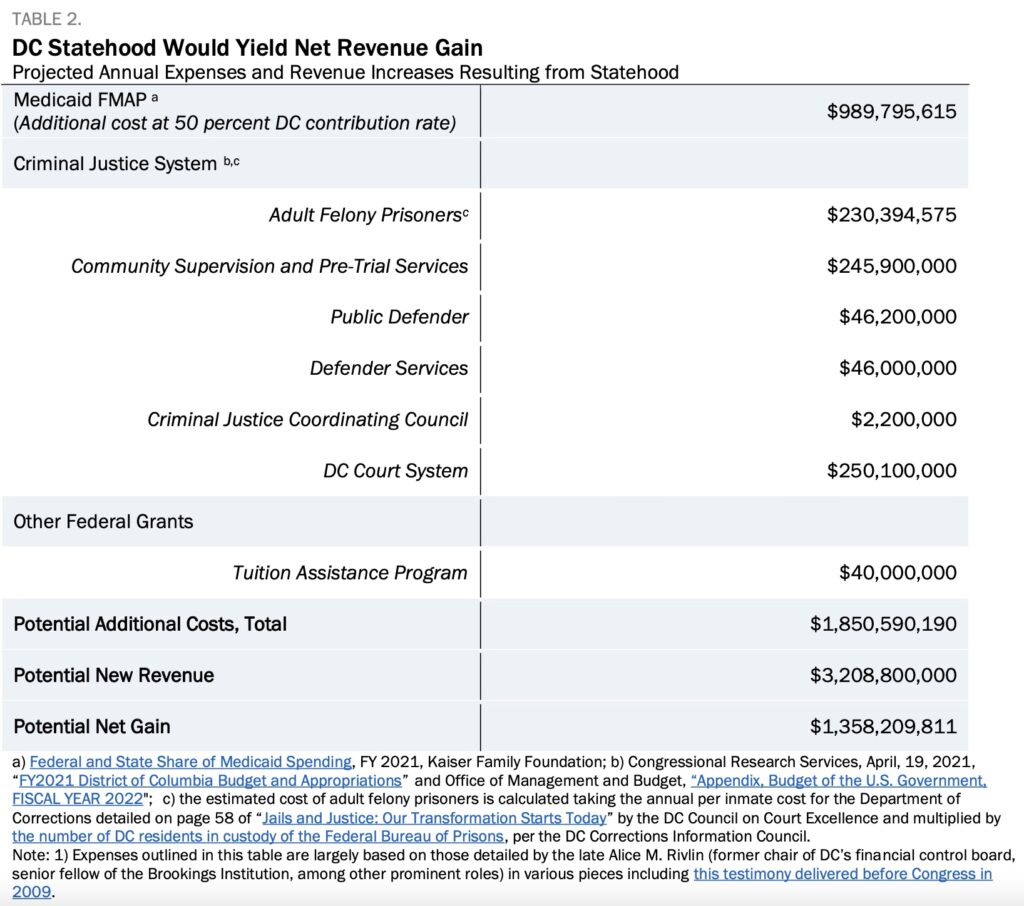

As a state, it is highly likely that DC would take on many of the expenses for which Congress provided relief under the Revitalization Act.[31] These costs are substantial, estimated at about $1.9 billion (Table 2). However, these estimates assume that the District would administer these services in the same manner as the federal government, which may not be the case. Even with expenses in this ballpark, the potential revenue gains surpass the costs. Net revenue gains from taxing non-resident income alone could be as high as $1.4 billion, equal to about 15 percent of local fund revenue in FY 2021. This represents a sizeable increase in resources to invest in transformative policy changes that advance racial justice and strengthen DC’s economy.

Other Revenue Implications of Statehood

Property taxes

As the nation’s capital, the District has limited ability to tax much of the real property within its own boundaries. Of the more than 11,000 properties in the District that receive property tax exemptions totaling more than $1 billion in forgone revenue, about 3,600 properties and $650 million of that are due to federal exemptions for federal properties and those of foreign governments.[32] Another 955 properties exempted from about $45 million in real property taxes include some individual organizations that were exempted and grandfathered in through special acts of Congress.[33] Statehood would give DC the option of taxing some of these properties.

Taxation and Regulation of Recreational Cannabis Sales

At the federal level, cannabis remains a Schedule I substance, which means that it is recognized as high potential for abuse, not legal, and has no accepted medical uses. DC has been able to create and regulate a medical cannabis industry, and it has decriminalized recreational use. However, DC’s lack of statehood and its unique position as a federal district subject to congressional oversight has hindered its ability to join many states in fully exercising their right to set their own local cannabis laws. In fact, an annual congressional budget rider prohibits DC from spending money to regulate and eliminate penalties associated with possessing, using, or distributing recreational cannabis.[34] It also means that the District is unable to tax recreational cannabis sales, thereby denying DC revenue that might be invested in Black and brown communities harmed by the racist War on Drugs.

Justice System Reforms

Even with its recent overhaul of the criminal code, with full control over the justice system the District might pursue more reforms by changing supervision, parole, and probation laws, imprisoning fewer people, and employing alternatives to incarceration that over the long term are less costly and more effective at reducing recidivism. The District Task Force on Jails & Justice report, Transformation Starts Today, offers recommendations for reforming these components of the justice system along with dozens of other recommendations for reducing the number of DC residents who are imprisoned. These range from upstream investments in priorities like housing and behavioral health, to community-informed solutions to increase safety in neighborhoods and public housing, to the removal of law enforcement from DC schools, and more.[35]

Reserves

As a federal district, DC also navigates prescribed uses of its locally generated revenue. One example is its reserves. The District has two federally mandated reserves created under the presidentially appointed Control Board. These reserves, totaling nearly $500 million, were put in place decades ago and built entirely from DC taxes and fees, but with strict mandates on reserve levels as well as limits on their use. For example, the law requires repayments to start within a year and be completed over two years, limiting their use in a recession.

- The Contingency Cash Reserve: This $320 million reserve can be used for “unforeseen needs that arise during the fiscal year,” such as a natural disaster, public health or public safety needs, or a 5 percent drop in revenue collections. It is normally tapped when funds can be replenished quickly, such as through a year-end budget surplus or federal recovery dollars. This structure leaves control over the reserve largely within the Mayor’s purview.

- The Emergency Cash Reserve: This $160 million reserve can be used to meet “extraordinary needs of an emergency nature, including a natural disaster or calamity,” or in a state of emergency declared by the Mayor. Lawmakers almost never tap this reserve.

To be clear, DC has an additional two locally mandated reserves that are also in need of reform to better address economic recessions and other kinds of crises that affect revenue collections.[36] But statehood would give the District the ability to repurpose the federally mandated reserve dollars, either to serve as a true “Rainy Day Fund” for use during recessions and emergencies with reasonable repayment requirements or one-time cash infusions into equity-enhancing public investments.[37]

Statehood Would Afford Greater Investments in Equity and Shared Abundance

By granting DC residents the rights to self-governance and federal voting representation, Congress would be correcting a historic harm that is rooted in anti-Blackness and perpetuates racial inequality. With fewer restrictions and the potential revenue boon that statehood offers, DC could take greater steps to minimize economic struggle, end displacement, house residents, guarantee jobs and income, and advance reparative policy in our most neglected communities. In doing so, DC would create a stronger, more equitable economy for the future.

Inequities by race, ethnicity, gender, immigration status, and intersecting identities undermine people, families, communities, and our economy as a whole. This nation’s history of structural racism and the discrimination and bias built into our economic, health, and social systems has left Black, indigenous, and people of color more likely to experience poverty, have poorer health, attend lower quality schools, and be shut out of wealth creating opportunities. These disparities are exacerbated for individuals who are also women, gender nonconforming, LGBTQIA, living with disabilities, or otherwise historically excluded from sharing fully in economic prosperity.

Currently, longstanding inequities in the District hold back Black and brown people and communities and its economic potential on the whole:

- Median income for Black households is roughly one-third that of white households in DC.[38]

- White households own 81 times the wealth of Black households and 21 times that of Latinx households.[39]

- More than one-quarter of Black people in DC lives below the poverty line ($28,000 for a family of 4), compared with 5 percent of white residents.[40]

- 85 percent of the city’s homeless population and over 90 percent of its public housing population is Black.[41]

- The District’s Black workers are five times more likely to be unemployed as white workers in this pandemic — the biggest gap in the nation — and they face the highest Black unemployment rate in the nation (when compared with states).[42]

- Black residents consistently make up three-quarters or more of COVID deaths since April of 2020.[43]

These inequities call for greater investments that address the exclusion of Black and brown people in DC’s economy. The potential revenue gain from statehood—which would be a reparative policy change in and of itself—could be used to fund policy change that repairs harms done over the course of the District’s history that perpetuate racial inequity today.

Nationally, if inequality by race, ethnicity, and gender were eliminated, our economy would experience dramatic, positive shifts, according to research by Robert Lynch for the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.[44] This research models income, poverty, and economic changes that would result from truly equal opportunity,[45] nationally, and found that:

- Black, Latinx, and Asian workers would earn nearly 61 percent more, on average, with women of color earning 88 percent more. Total income in the United States would increase by about one-third, or $4.3 trillion.

- GDP would be 33.5 percent higher and tax revenue to invest in thriving communities would jump by about $1.2 trillion at the federal level and $636 billion at the state and local level.

- The national poverty rate would drop by nearly 40 percent, overall, and the rates for Black and Latinx people by about half.

Unpublished analysis by Dr. Lynch and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities of more limited data for DC, using the same model and in 2020 dollars, finds that equal opportunity among the Black, Latinx, and white populations would result in:

- Average incomes for Black workers rising by 160 percent, from about $45,000 to about $116,000. And in fact, because income tends to rise with age and DC’s Black population skews older than its white population, average income for Black households would outpace that of white households by about $6,000.

- Average incomes for Latinx workers going up by 90 percent, from about $56,000 to about $107,000.

- Average income gains for Black and Latinx workers combined resulting in about $21.1 billion more in aggregate income that would boost income tax revenue for the District to further invest in communities and shared prosperity.

While this model reflects a hypothetical scenario, a growing body of research has deepened collective understanding of the harmful effects of inequality for economic growth, innovation, and the distribution of power and resources.[46] Income inequality in the District as measured by the Gini Index is extreme and surpasses that of every other state and the national as a whole, a status shared only by Puerto Rico.[47]

Statehood would confer upon DC residents voting rights and representation that never should have been denied, addressing an ongoing injustice that has long disenfranchised a largely Black jurisdiction and is rooted in anti-Black racism. It also would have major fiscal benefits. The resulting expansion of District revenues would help DC take further action to address the extreme level of inequity rooted in a racist history that continues to hold it back. That means public investment in services that meet needs, repair harms, expand opportunity, and allow individuals to live to their fullest.

[1] See pages I-10 to I-12 in “FY 2021 Approved Budget and Financial Plan – Congressional Submission,” Office of the Chief Financial Officer, District of Columbia.

[2] 2016 General Election Certified Election Results, retrieved from https://electionresults.dcboe.org/election_results/2016-General-Election

[3] Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital (The University of North Carolina Press, 2017), pg. 165.

[4] Michael Leachman, Michael Mitchell, Nicolas Johnson, and Erica Williams, “Advancing Racial Equity With State Tax Policy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 15, 2018.

[5] Asch and Musgrove, pg. 44, 59-61.

[6] Asch and Musgrove, pg. 146, 150-151, 154.

[7] Asch and Musgrove, pg. 45, 98.

[8] Asch and Musgrove, pg. 156, 160.

[9] Meagan Flynn, “How White fears of ‘Negro domination’ kept D.C. disenfranchised for decades,” Washington Post, April 14, 2021.

[10] George Derek Musgrove and Chris Myers Asch, “Democracy Deferred: Race, Politics, and D.C.’s Two-Century Struggle for Full Voting Rights,” Statehood Research DC, March 2021.

[11] Musgrove and Asch, “Democracy Deferred.”

[12] Leachman, Mitchell, Johnson, and Williams, “Advancing Racial Equity With State Tax Policy.”

[13] Hunter Blaire, et al., “Preempting progress,” Economic Policy Institute, September 30, 2020.

[14] US Census Bureau, “Population Estimates, July 1, 2021 (V2021) – Birmingham City, Alabama,” Quick Facts, accessed December 16, 2022.

[15] Emma Platoff, “Rejecting appeal, Texas Supreme Court blocks Austin’s paid sick leave ordinance,” Texas Tribune, June 5, 2020.

[16] Jessica Milli, “Access to Paid Sick Time in Austin, Texas,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, August 2017.

[17] District residents gained the right to vote for United States President and Vice President in 1963 and for a non-voting representative in the U.S. House in 1970. For a brief summary on the development of the Home Rule Act, see “D.C. Home Rule,” Council of the District of Columbia.

[18] Lauren Ober, “Once-Controversial DC Needle Exchange Found to Save Money—And Lives,” WAMU, September 25, 2015.

[19] Karina Elwood, “What do Biden’s mass marijuana pardons mean for DC?” The Washington Post, October 7, 2022.

[20] Christian Blood, “Sen. Cruz introduces bill to stop non-citizen voting in nation’s capital,” KTSA, November 18, 2022, and Julio Rosas, “Congressional Republicans are Ready to Take Down Proposed DC Criminal Code,” Town Hall, November 10, 2022. Note that members of Congress also at times attempt to move legislation that only applies to DC, such as the proposal to experiment with a flat federal income tax for DC residents. See Meghan Clyne, “DC May Be a Flat Tax Laboratory,” New York Sun, November 30, 2005.

[21] US Census Bureau, “Black or African American alone, percent (V2021),” Quick Facts, accessed December 16, 2022.

[22] Based on the voting power of each US senator, the average Black American receives 75 percent of the representation of the average white American, according to a New York Times analysis. David Leonhardt, “The Senate: Affirmative Action for White People,” New York Times, October 14, 2018.

[23] All forty-one states that levy comprehensive income taxes tax income earned within their borders by non-residents in the form of wages, rents, or self-employment income, although 17 have reciprocity agreements with one or more (usually neighboring) states under which they agree to forgo taxation of non-residents’ wages (only) in exchange for the other state forgoing taxation of their residents’ wages earned there. See, Tonya Moreno, “Do You Have to File a State Non-Resident Return?,” the balance, March 24, 2022,.. It also should be noted that taxing non-resident income is not the same as a commuter tax, which some states might levy on out of state commuters to achieve goals like reducing congestion, incentivizing ride-sharing, or mitigating pollution.

[24] CBPP analysis of US Census Bureau American Community Survey 2015-2019 public use microdata sample. About 16,000 non-resident District earners reside in places other than MD or VA.

[25] CBPP analysis of US Census Bureau American Community Survey 2015-2019 public use microdata sample finds that there are 6 times as many Marylanders and 5 times as many Virginians with earnings in DC than DC residents with earnings in those two respective states.

[26] This is a rough estimate that assumes DC’s current tax rates and brackets would be applied in full to non-resident income as is done in states like Minnesota, New Jersey, New York. The effective tax rate is based on the share of income DC residents pay in income taxes, which could be lower or higher for non-residents. Because median income of non-residents earning in DC is higher, that might imply a higher effective tax rate.

[27] For a discussion of the court decisions around DC taxation of businesses providing professional services and non-salaried non-residents, see Charles Butler, Bishop v. District of Columbia: Taxation of Unincorporated Professionals’ Net Income Violates Home Rule, Volume 29, Issue 4, Summer 1980.

[28] The Office of the Chief Financial Officer estimates the effective income tax rate for DC in tax year 2023, when recent tax changes are in effect, at 5.6 percent. This rate includes all deductions, exemptions, and credits, including some large credits likely not be available to non-residents, such as the DC Earned Income Tax Credit or the property tax circuit breaker for primary homeowners and renters. The OCFO’s effective income tax rate was developed using the agency’s individual income tax simulation model and is both more conservative and precise than similar prior methods of calculating an effective income tax rate by dividing total income tax collections by total earned income (adjusted downward by the value of standard deductions).

[29] For a brief but thorough accounting of this history, see the following: Jon Bouker, “Appendix I: The DC Revitalization Act: History, Provisions and Promises,” Building the Best Capital City in the World, Brookings Institution, December 2008; CSPAN’s coverage of US Office of Management and Budget Director Franklin D. Raines’ testimony before a congressional subcommittee on the District of Columbia in February 1997; and “D.C. Home Rule,” Council of the District of Columbia.

[30] “Norton Says Lack Of Statehood Cost D.C. Tens To Hundreds Of Millions Of Dollars In Earmarks In Final Fiscal Year 2023 Appropriations Bills,” December 22, 2022.

[31] Alice Rivlin, “If the District of Columbia Becomes a State: Fiscal Implications,” Testimony to the Council of the District of Columbia, July 2009.

[32] Properties Exempt from taxation in TY 2022 for Tax Types: DC, E0-E9 and US, Office of Tax and Revenue, Office of the Chief Financial Officer, District of Columbia.

[33] District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report, Office of Revenue Analysis, Office of the Chief Financial Officer, District of Columbia, December 2020, and § 47–1002. Real property — Exemptions, Code of the District of Columbia.

[34] See Doni Crawford, First in Line: A Reparative Approach to Recreational Cannabis Policy,

February 16, 2021.

[35] Jails & Justice: Our Transformation Starts Today, Phase II Findings and Implementation Plan, Council for Court Excellence, February 2021.

[36] Tazra Mitchell, The COVID-19 Recession is DC’s Rainy Day, but Reserve Rules Limit its Response, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, February 3, 2021.https://www.dcfpi.org/all/the-covid-19-recession-is-dcs-rainy-day-but-reserve-rules-limit-its-response/

[37] Ibid

[38] Erica Williams and Tazra Mitchell, Large Black-White Disparities in Poverty and Income Persisted in 2021, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, September 15, 2022.

[39] Kilolo Kijakazi, Rachel Marie Brooks Atkins, Mark Paul, Anne E. Price, Darrick Hamilton, Willian A. Darity Jr, The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital, Urban Institute, November 2016.

[40] Erica Williams and Tazra Mitchell, Large Black-White Disparities in Poverty and Income Persisted in 2021, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, September 15, 2022.

[41] Point-In-Time Dashboard, The Community Partnership for the Prevention of Homelessness, 2022, and “FY2021 Consolidated Annual Performance Evaluation Report (Draft) Addendum (Figure 1),” Department of Housing and Community Development, January 2022.

[42] State unemployment by race and ethnicity, Economic Policy Institute, Updated December 2022

[43] 2021 – 2022 Coronavirus Data, Government of the District of Columbia, Mayor Muriel Bowser, February 28, 2022 (last date for which data were updated).

[44] Robert Lynch, June 2021, The economic benefits of equal opportunity in the United States by ending racial, ethnic, and gender disparities, Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

[45] Equality of opportunity in this analysis is defined as when all racial, ethnic, gender groups earn the same average total money income as white, non-Latinx males, adjusted by age distribution. This results in an increase in hypothetical earnings for women and people of color that reduces poverty and increases tax revenue and GDP. Lynch notes that policies to create equal opportunity would benefit white males, as well, but these benefits were not assessed and included in his study.

[46] See examples in Erica Williams, DC’s Extreme Wealth Concentration Exacerbates Racial Inequality, Limits Economic Opportunity, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, October 2022.

[47] DCFPI analysis of 2021 American Community Survey data, Table B19083. DC has a Gini index of 0.531, which is statistically higher than any other state and the nation as a whole. It is not statistically different from the Gini index for Puerto Rico of 0.542. See the definition of the Gini Index here.