As the District enters the second year of the pandemic, revenues are projected to fall by $2.5 billion over four years and deep cuts in services could be on the horizon.[1] To soften these losses, lawmakers should change the restrictive rainy day fund rules that make most of DC’s savings unavailable. The Mayor and DC Council tapped nearly $213 million in reserves for the fiscal year (FY) 2021 budget, but the remaining $1.2 billion is not easily accessible to address the painful harm of the pandemic on residents, businesses, and the economy. If the restrictive rules remain in place, DC could be forced to make cuts in services to residents struggling to meet basic needs and businesses at risk of closing, while leaving a substantial amount of money in the bank.

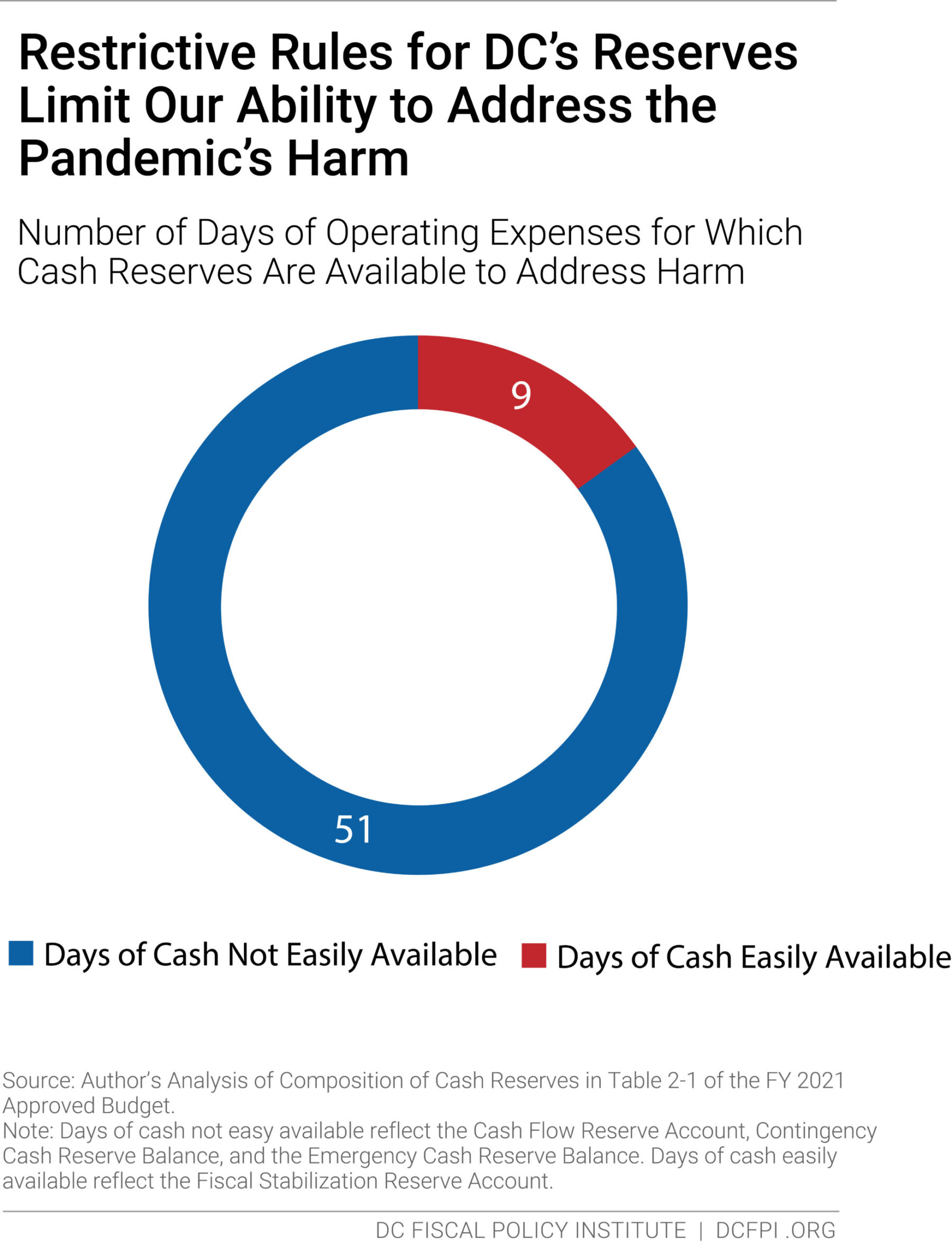

The District’s $1.4 billion in reserves available in the approved FY 2021 budget are spread across four funds, three of which are not well designed to assist in an economic downturn. DC built up these reserves to have cash on hand to meet 60 days of operating expenses available for challenging times, a target recommended by the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA). Yet restrictive rules essentially leave the District with nine days of easily available cash—rather than 60—even when they are needed most. This defeats the purpose of reaching a 60-day cash reserve

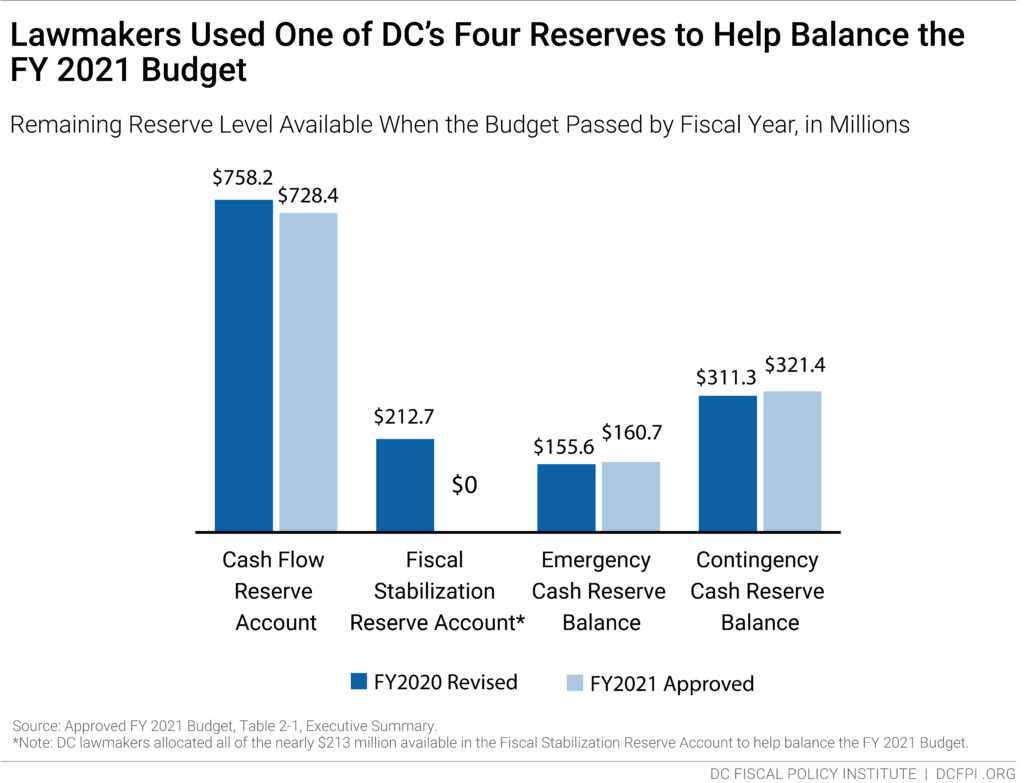

DC’s two locally-mandated reserves, which total nearly $950 million in the FY 2021 budget, have completely different rules that govern their use during a recession and how quickly they must be replenished.

- The Cash Flow Reserve Account: This almost $730 million reserve (half or about 31 days of DC’s savings) cannot be used as a rainy day fund in a recession, when the fallout of shrinking revenue and increased demand for services stretch beyond a year. This fund is used only for short-term cash-flow needs since any money used must be repaid in the same fiscal year.

- The Fiscal Stabilization Reserve: This fund, which accounts for one-seventh of DC’s reserves and totals nearly $213 million (9 days of revenue), is the only one that lawmakers are currently and readily able to use. This locally-mandated fund is available for use in a recession because repayments come from future budget surpluses. The FY 2021 budget tapped this entire reserve, and will begin to replenish it in FY 2023. As a result, no more funds are available from this reserve until FY 2024.

The District’s two federally mandated reserves, which total another $480 million, require repayments to start within a year and be completed over two years, limiting their use in a recession (Figure 2).

- The Contingency Cash Reserve Balance: This $320 million reserve (13.5 days of revenue) is normally used when it is likely that funds can be replenished quickly, such as through a year-end budget surplus or federal recovery dollars. This structure makes the reserve available to the Mayor but effectively inaccessible to the DC Council in the budget process. While the Mayor uses this reserve frequently, the Council has never tapped the Contingency Reserve on its own.

- The Emergency Cash Reserve Balance: This $160 million reserve (nearly 7 days of revenue) can be used to meet “extraordinary needs of an emergency nature, including a natural disaster or calamity,” or in a state of emergency declared by the Mayor. Lawmakers almost never tap this reserve.

How to Improve the District’s Reserve Rules

The Mayor and DC Council should take steps now to make more of the reserves available to address the harm of the pandemic. In particular, they should make the following improvements:

- Allow funds in the $730 million Cash Flow Reserve Account to be tapped in an economic downturn and repaid when the economy recovers.

- Work with Congress to eliminate as many of the restrictions on the Emergency Reserve and Contingency Reserve as possible. Given that the Control Board disbanded nearly twenty years ago, and DC has managed its finances well, giving DC more autonomy over its finances only makes sense.[2]

DC’s Reserves Are Poorly Designed for a Recession

The District has policies that work to build adequate reserves, but other rules unfortunately make it very hard to use reserves when needed. While some of these rules are imposed by Congress, local rules fully restrict half of DC’s reserves.

DC’s Cash Flow Reserve Account Has Too Narrow a Purpose

Half of DC’s reserves—$728 million in FY 2021—is in the Cash Flow Reserve Account that cannot be used as a traditional rainy day fund. The DC FY 2021 budget doesn’t use any funds from this reserve, and without a change to the rules, the District cannot tap it to help balance the budget in FY 2022 or any future deficits.

Lawmakers established this reserve about a decade ago with two goals:

- To help DC build up cash on hand to equal 60 days of operating costs, as recommended by government finance experts. The Cash Flow Reserve Account itself creates 30 days of cash.

- To support DC’s cash flow needs. DC’s major tax collections come in large amounts at selected points in time, such as property tax bills paid in September and March. Yet the basic expenses of government—such as payroll or Medicaid expenditures—occur every month. The Cash Flow Reserve Account creates resources to pay bills when cash on hand may otherwise be low, just before major tax payments.

Rules governing this reserve require that any funds used in a given year be repaid by the end of the year, which is consistent with its cash flow purpose. But this means the substantial reserve cannot be used at all to address the fallout of the recession on residents or businesses. Under current law, for example, the District cannot use the cash flow reserve to increase the budget on a one-time basis for emergency rental assistance in FY 2021, because the money spent would have to be repaid by the end of the same year.

While having money on hand for cash flow needs makes sense, the District doesn’t need to restrict this amount of funding in the Cash Flow Reserve, for two reasons. First, the District has never used more than 75 percent of the Cash Flow Reserve at any one point, which suggests up to 25 percent of the reserve could be used for other purposes without putting its cash flow needs at risk. Second, and more important, the District has other options to find money for cash flow needs, in particular, by borrowing money for very short periods of time (less than a year). Known as temporary revenue anticipation notes, this is a cost-effective tool used by cities and states across the country. In the Great Recession, before the Cash Flow Reserve was created, the District met its cash-flow needs through short-term borrowing. The cost was just $4.5 million in FY 2009 and $2.3 million in FY 2010—primarily for interest costs. Given that interest rates today are incredibly low, borrowing costs for short term loans today would likely be very small.

DC residents would be better served if lawmakers were able to use the Cash Flow Reserve as a rainy day reserve during economic downturns–that is, using funds without having to replenish them the same year at times when businesses are closing, jobs are disappearing, and families are struggling to put food on the table.

Because this would reduce money available for cash-flow purposes, the District would need to take on short-term borrowing, but as noted this would be low-cost and lawmakers wouldn’t have to worry about a downgrade in their bond rating (Breakout Box).

In short, this means DC could tap hundreds of millions to meet human needs and prevent cuts in the pandemic, while incurring modest short-term borrowing costs. The District could then rebuild the Cash Flow Reserve Account when the economy recovers.

Emergency Reserve and Contingency Reserve Operate Under Unwarranted Federal Restrictions

Two of DC’s reserves—the Emergency Reserve and the Contingency Reserve—are required under federal law and were mandated by the Control Board nearly two decades ago. While federally mandated, the money set aside is generated entirely by DC taxes and fees. The District has $480 million in these reserves in the FY 2021 budget.

The Congress created these reserves with notable restrictions on their use.

- The Emergency Reserve—$160 million—can be used to meet “extraordinary needs of an emergency nature, including a natural disaster or calamity,” or in a state of emergency declared by the mayor. This means that the reserve cannot be used in a recession unless the mayor declares an emergency.

- The Contingency Reserve—$320 million—can be used for “unforeseen needs that arise during the fiscal year,” such as a natural disaster, public health or public safety needs, or a 5 percent drop in revenue collections.

Unfortunately, the replenishment rules set in federal law make these reserves largely inaccessible as a rainy day reserve. DC is the only locality that federal law requires to repay any funds used from these reserves within two years, with at least 50 percent repaid in one year. When DC faces a multi-year economic slowdown, like the one we face now, this rapid repayment requirement makes it difficult to use them.

The following budget examples show the limited ways in which DC has leveraged these funds since the pandemic arrived:

- The District kept these reserves fully funded in FY 2021 and future years.

- The District did not use the Emergency Reserve in FY 2020 and has no plans to use it in FY 2021.

- The District used $50 million of the $320 million Contingency Reserve in the revised budget for FY 2020, but also set aside about $24 million to start replenishing it, leaving just $26 million to be spent. Lawmakers did not appropriate anything from the Contingency Reserve in the FY 2021 budget.

- It is worth noting that Mayor Bowser has used the Contingency Reserve numerous times in recent years—outside the budget process—including in FY 2020. In some cases, these reflect temporary uses, such as fronting funds for COVID expenses that ultimately will be paid for with federal relief funds. In other cases, the Mayor has used the Contingency Reserve to spend money outside the budget process with the hope that the funds will be replenished with surplus funds identified at the end of the fiscal year.

The repayment requirement effectively keeps the DC Council from using the Contingency Reserve in the budget, since they also would have to budget for repayment. The Council has never initiated steps to use this fund. Instead, the repayment rules give the Mayor access to the Contingency Reserve outside the budget process—without requiring input from the Council—when it is likely the funds can be repaid quickly.

“Fiscal policy experts warn that rules requiring rapid replenishment of reserves makes them difficult to use.”

Fiscal policy experts warn that rules requiring rapid replenishment of reserves makes them difficult to use.[3] But they especially do not make sense for the federal government to impose them on DC now. The federal government does not set rules on rainy day funds for any other city or state, and the rationale for restricting DC’s finances ended twenty years ago in the Control Board era. DC has had two decades of balanced budgets and stable finances since then.

DC’s Fiscal Stabilization Reserve is Our Only Flexible Rainy Day Fund

The Fiscal Stabilization Reserve is the most flexible part of DC’s reserves, although it is a small portion (one-seventh of DC’s rainy day funds). The rules for this fund allow its resources to be used in a recession, and repayment comes from future budget surpluses. This means the Mayor and Council do not need to plan for its replenishment when funds are used. The District fully tapped this reserve (nearly $213 million) to help fund services for DC residents and businesses in FY 2021. While helpful, this means that no funds are available from this reserve until FY 2024.

Building up Rainy Day Reserves and Using Them When Needed is Smart Fiscal Policy

Fiscal experts recommend that states and cities build up reserves in strong economic times—then draw on them when the economy is declining. When the economy is strong and generating higher levels of tax revenues, saving some of the revenue makes sense for two reasons:

- It creates a pool of savings that can be used to maintain public services in an economic downturn—like funding for schools, transportation, and the safety net—or to respond to other unexpected emergencies, like a natural disaster or public health crisis.

- Setting aside some revenues when the economy is strong—rather than using all of the growing revenue—prevents governments from making commitments that cannot be maintained when the economy slows down.[4]

Spending reserves in a downturn is as important as building up reserves when times are good. Recessions are marked by higher unemployment and an increased demand on the social safety net as well as a drop in tax collections due to reduced incomes and consumption. Without savings, states and cities are forced to cut services, raise revenues, or do both in a recession. Cuts in services, such as education, housing, health, or transportation can make the economic downturn even worse. Laying off government workers or stopping planned pay increases means less money in residents’ pockets to spend in the local economy. Cuts in social services can lead to increased food or housing insecurity. Some service cuts—like those in education, health care, or transportation—which keep the economy strong—can cause long-term harm.

That’s why state and local fiscal policy experts recommend spending reserves when times are tough. Fiscal policy experts recommend that states and cities create rainy day funds with rules that make them easy to draw from in a recession. In particular, experts warn that rainy day funds are hampered if they include rules to repay withdrawn funds in a short period of time—a problem that affects the vast majority of DC’s reserves.[5]

The 60-Days Reserve Standard Embraced by DC Assumes Reserves Will Be Used in Recessions

A decade ago, DC’s leaders set (and in 2019, met) the goal of having 60 days of operating expenses in reserve—about one-sixth of the District’s budget—based on a standard from the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA). This standard is intended to encourage states and cities to build up reserves that can be drawn down when needed.

The GFOA standard notes that, “It is essential that governments maintain adequate levels of fund balance to mitigate current and future risks (e.g., revenue shortfalls and unanticipated expenditures) and to ensure stable tax rates.” [6] [emphasis added]. In other words, the goal of the standard is to build up adequate reserves so that the funds are available to be used when needed. Yet, DC’s restrictive rules over the use of most of its reserves defeat the purpose of reaching a 60-day cash reserve.

The District’s reserves policies leave it with just 9 days of flexible operating reserves—in the Fiscal Stabilization Reserve—and 51 days of effectively unusable reserves. The District fully tapped the entire Fiscal Stabilization Reserve for FY 2021, making the ability to use some of the remaining reserves for the ongoing health and economic crisis even more important.

Time to Fix DC’s Reserve Rules

The District should work now to make it easier to use more of its budget reserves during hard times. In particular, the Mayor and

- Modify the Cash Flow Reserve Account to allow it to be used in a recession like the Fiscal Stabilization reserve. This would mean allowing funds to be withdrawn, with repayment coming from future budget surpluses.

- Encourage Congress and President Biden to give DC more control over its Emergency and Contingency Cash Reserve Accounts. This could mean fully eliminating the DC reserve requirement in federal law. (Congress does not require any city or state to maintain reserves.) That would allow DC to govern these reserves by local rules. The District could also request that Congress eliminate the replenishment rule, allowing DC leaders to set up their own replenishment rules.

This could allow DC to help more residents avoid eviction or hunger, assist more businesses struggling to stay open, support child care centers, and homes that are vital to our economy but face special pressures now, and more. These actions would not only help directly affected residents and businesses, they would help the entire DC economy recover from the recession by keeping funds flowing to landlords, small businesses, and more.

[1] CFO’s Revenue Forecast for the FY 2021-2024 Financial Plan, December 2020 and February 2020. Note that the Comprehensive Annual Financial Audit for FY 2020 (published February 1, 2021) shows that the fund balances for the Cash Flow Reserve and the Fiscal Stabilization Reserve are slightly higher than the FY 2020 revised budgeted level.

[2] The federal government required the District to establish the Emergency and Contingency Reserves at a time when the city still was managed by a federal financial control board, and trust of the city’s ability to manage its finances was low. As a result, Congress imposed several rules governing the fund that are far stricter than the rules most states place on their rainy day reserves.

[3] Jeff Chapman et al., “State Rules Can Complicate Rainy Day Fund Withdrawals,” Pew Charitable Trusts, May 12, 2020.

[4] See, for example, Josh Goodman, “Rainy Day Funds Help States Weather Fiscal Downturns,” Pew Charitable Trusts, April 9, 2020.

[5] See, for example, “State Rainy Day Funds Likely to Fall Short,” National Conference of State Legislatures, April 23, 2020.

[6] Government Finance Officers Association, “Best Practices: Fund Balance Guidelines for the General Fund,” accessed January 15, 2021.