Chairperson McDuffie and members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify. My name is Tazra Mitchell. I am the policy director at the DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI), which is a nonprofit organization that promotes budget choices to address DC’s racial and economic inequities through independent research and policy recommendations.

Centuries of discrimination and exploitation have concentrated the vast majority of wealth in the hands of the few, leaving Black DC residents with very little wealth, compared to white residents. While we don’t have equivalent local data, nationwide white households hold 87 percent of all wealth, and the top 10 percent of white households hold 65 percent of all wealth.[1] District policymakers can advance wealth equity by fixing our tax system, which rather than being a tool to reduce racial wealth inequities, protects wealth concentration through myriad tax preferences, exemptions, deductions, loopholes, and low tax rates.

We currently have a District tax system where the richest 20 percent of residents pay less in taxes as a share of income than the bottom 80 percent, and where our estate tax has eroded even as wealth and income have become more concentrated.[2] Because white residents account for the vast majority of DC’s richest residents, undertaxing residents at the top privileges white residents and white wealth—and this comes at the expense of public investments in underserved communities that advance racial justice.

Even as the pandemic’s economic fallout has deeply harmed tens of thousands of DC residents, well-off residents have largely gone by unscathed in the last year, seeing their wealth, income, and savings grow. Against this backdrop, and with the District facing significant investment needs, building wealth equity in Chocolate City requires that policymakers end the special tax treatment that well-off residents and profitable corporations enjoy, specifically by:

- Raising income taxes on high-income residents and profitable corporations;

- Taxing wealth and property more; and,

- Scaling back loopholes and special tax benefits for high-income and wealthy residents.

Income and wealth are different but go hand in hand. For example, high incomes allow people to build wealth, and that wealth in turn produces income that often goes untaxed or gets taxed at lower rates than wage income. The tremendous concentration of wealth among white people has been driven by racism, meaning that the wealth of white households is more than it would have in the absence of policies to support white supremacy. Given that, highly progressive taxation aimed at high-income residents and high-wealth residents is a necessary—and in fact the only practical—step to addressing the harm of centuries of systemic racism driving income and wealth inequality.

The funding raised would both reduce wealth concentration and could fund transformative investments in Black and brown households and communities, like baby bonds.

The Tax System Upholds DC’s Deep Racial Wealth Divide

DC’s wealth gap is staggering: the average Black household in DC has under $4,000 in net assets—essentially no cushion to weather a crisis, like a pandemic—while the average white wealth is 81 times that.[3] This average masks the extreme wealth that is at the tip of the scale: nationwide, the 400 richest American billionaires have more total wealth than all 10 million Black American households combined.[4] Income is highly racialized in DC but is less concentrated than wealth.

Tax policy is not race neutral. It operates in invisible ways that hamper Black wealth generation and protect white economic dominance and wealth.[5] A factor that perpetuates the concentration of income and wealth is the tax system’s advantageous treatment of inherited wealth, capital gains, dividends, and corporate and non-corporate business income. These advantages in the US and DC tax codes allow higher-income residents to build more wealth, increase the value of existing assets, and increase the wealth that they pass to future generations. Since most wealth—87 percent—is held by white households, these tax preferences favor white households far more than Black households and reinforce wealth concentration among white households.

Similarly, structural barriers that leave Black and brown people overrepresented among households with low-and moderate-incomes and with the least wealth shows up on their tax returns, as research from tax Dorothy Brown, a renowned tax scholar, shows. Discrimination in the labor market and fewer educational opportunities limit earnings andaccess to good jobs with fringe benefits, which affects both the taxes that Black and brown people pay and the tax breaks for which they’re eligible.[6] Dr. Brown’s research shows how tax subsidies for home ownership also fuel the racial wealth gap in the US, given that the mortgage interest rate deduction largely benefits white high-income earners. Less well known is that the tax code rewards net gains from home sales, which advantages white taxpayers because homesappreciate the most in virtually-all white areas, not mixed or mostly-Black areas:

“Today, if you sell your home at a gain, you can receive up to $500,000 of gain tax-free. If, however, you sell your home at a loss, you get no tax break. (Contrast that with the way the tax law allows losses to be deductible when you sell stock.)…tax subsidies that reward homeowners who sell their homes at a gain and punish those who sell their homes at a loss still disproportionately benefit white homeowners and their preferences—helping far too few Black homeowners along the way.”[7]

This is what researchers mean when they say that taxes have long operated like “the gears and levers of white supremacy.”[8]

Tax Policy Is Our Key Tool for Building Wealth Equity

Tax policy is our key tool to ensure there is adequate revenue to meet growing needs so all DC residents can benefit from our city’s growing prosperity, gain economic stability, and build wealth. DC can craft fiscal policy to advance racial and economic justice—and we have made great strides towards this goal, by enacting a strong Earned Income Tax Credit, a Schedule H tax credit, and low marginal tax rates for people with lower incomes, for example.

Yet, DC’s highest income and wealthiest residents are undertaxed. The richest one percent pay a smaller share of income in DC taxes than everyone other than residents with incomes under $25,000. And the richest 20 percent of DC residents pay less of their income in DC taxes than the bottom 80 percent combined.[9] In a progressive tax system, the richest people should pay a much higher share of their income in taxes than lower-income families with little or no wiggle room in their family budget. That’s the standard against which we should be measuring ourselves.

Given DC’s vast income and wealth inequality, and its roots in systemic racism, making DC’s tax system more progressive by increasing taxes on high incomes and wealth are necessary steps to racial wealth equity. The following ideas meet this principle.

Raising income taxes on high-income residents and profitable corporations

Because wealth produces income and high incomes allow people to accumulate wealth, levying higher income tax rates at the top, for example, is just one of many ways of taxing the income of wealthy individuals. Today, a nurse or teacher pays almost the same income tax on additional earnings as a hedge fund manager in DC. Meanwhile, the city’s richest residents have benefitted from hundreds of millions in federal tax cuts passed in 2017. The District should enact a tax increase on individuals with taxable income of more than $250,000. This would raise taxes on just 3 percent of taxpayers in the District, and more than 90 percent of the tax increase would be paid by those earning about a million dollars or more,[10] taking up just a fraction of their recent increase in wealth.

Also, because the District allows married couples to file separately based on each spouse’s income, while keeping the information on the same return, some couples would not face a tax increase until their combined taxable income is over $500,000.

The District should also consider raising taxes on profitable corporations, who have seen enormous pandemic profits, as the District’s recent forecast shows. More than half of corporations pay only the minimum tax amount because they are able to claim enough deductions and credits to reduce their tax responsibility to the minimum level.[11] Yet, the District enacted unnecessary cuts to the corporation franchise starting in 2015, lowering it from 9.975 percent to 8.25 percent by 2018. Research presented to the DC Tax Revision Commission showed that a cut to the franchise tax wasn’t warranted. The Commission’s report noted that DC had outperformed surrounding jurisdictions in business and job growth in the last decade, despite having a higher corporate income tax rate.[12] The Commission’s recommendation to cut corporate taxes came from a desire of the Commission’s corporate sector representatives to get something, not from the research the Commission conducted. Reducing taxes for profitable corporations meant that a business’s income is now taxed at a lower rate than residents with moderate incomes in DC.

Making the most profitable businesses pay their fair share would raise revenues that could be reinvested in programs that build Black and brown wealth and stability.

Taxing Wealth, Inheritances and Property

Another way the District could build more broadly shared prosperity is by taxing the assets of the wealthy, by strengthening the estate tax, raising taxes on capital gains, and raising taxes on very expensive homes. Expanded wealth taxes are an add-on to more progressive personal and corporate income taxes and other progressive taxes, not a substitute. DC could take the following steps to deconcentrate wealth:

- Strengthen the estate tax. DC policymakers have substantially eroded DC’s estate tax, our most progressive revenue source, over the past several years. DC has repeatedly increased the size of estates that are allowed to be passed to heirs completely tax free. During last year’s budget process, Council approved legislation to lower the threshold from $5.6 million to $4 million, but greater reversal is needed given the prior threshold was $1 million. (Maryland has both an estate and an inheritance tax, which is levied on the recipients of the estate instead of the deceased person’s estate.)

- Raise the capital gains income tax rate. Much of wealthy households’ income comes from capital gains, which are profits from selling an asset that has grown in value, such as corporate stock or real estate. Income from capital gains currently enjoys several tax advantages,[13] and raising the capital gains income tax rate is a simple way to reduce those advantages at the top. This would simply require the District to set separate income tax rates for capital gains from other income, as some states do.

- Decouple from federal Opportunity Zone capital gains tax cuts. Wealthy residents also benefit from capital gains tax breaks for investments in designated Opportunity Zones (OZs), a federal tax break that flows through DC’s tax code. The District should decouple from this law, which would require capital gains income associated with OZs to be taxed in the normal fashion, as ordinary income. There is already considerable national evidence that the program has become a windfall for rich investors rather than a benefit to zone residents with low-income it was ostensibly intended to help. OZ programs also could fuel further displacement and gentrification.

- Raise taxes on high-value homes. White households are still far more likely to own homes than Black and brown households in DC, and the typical value of Black homes is only two-thirds of the value of white homes.[14] As home values soared over the past decade, white residents received most of the increase, because they are more likely to own homes—and especially high-values homes. White residents got 77 percent of the increase in aggregate home values in DC between 2010 and 2019, while only 12 percent went to Black households and 11 percent went to Latino households.[15] Considering the District has the lowest property tax rates in the region, increasing taxes on the wealthiest DC residents through a graduated property tax structure would enable DC to finally tackle some of its deepest inequities and boost housing stability.

For high-value homes, lawmakers could also consider eliminating the property assessment cap, which limits the increase to a homeowner’s taxable assessment to 10 percent per year, even if a home’s full value increases by more than that. The District of Columbia levies a transfer tax that is based on a property’s sale value, with a higher rate for residential properties exceeding $400,000 assessed. DC lawmakers could also create a higher tax rate for high-value properties, such as those valued greater than $2 million. Policymakers must make several decisions in designing a tax on high-value housing. The tax could include all homes or second or vacation homes only, for example.

Ending or scaling back loopholes and special tax benefits for high-income and wealthy residents

DC’s tax system is riddled with loopholes and inequities that hold us back. As a result, our tax system does almost nothing to address racial income inequities. The average income of non-elderly white households is 2.11 times higher than the average Black household income in DC before taxes are considered, according to ITEP, and 2.08 times higher when taxes are taken into account.[16] We should see a more significant drop. We can make headway by supplementing the income tax and wealth tax ideas above with limiting tax deductions that disproportionately benefit high-income taxpayers in DC.

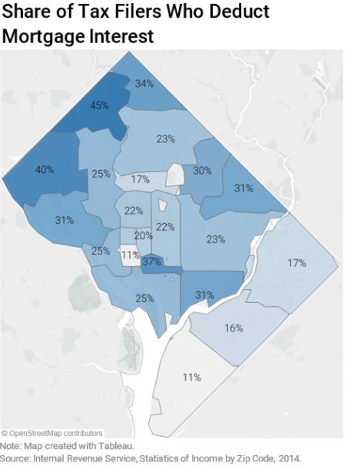

The District should take a critical look at the mortgage interest deduction, which is one of the many hidden policies that benefit higher-income residents and bolster wealth inequality. This deduction largely benefits the District’s wealthiest neighborhoods and highest-income residents, and costs the city over $40 million in foregone local revenue every year due to federal conformity.[17] In 2014, about 40 percent of tax filers in the zip codes west of Rock Creek Park—DC’s wealthiest communities—claimed this deduction, compared to fewer than 17 percent of tax filers living east of the Anacostia River (see graphic below). And the average amount of mortgage interest deducted per tax filer (whether claiming the MID or not) was 8 times larger in northernmost Ward 3 compared to the southern part of Ward 8.[18]

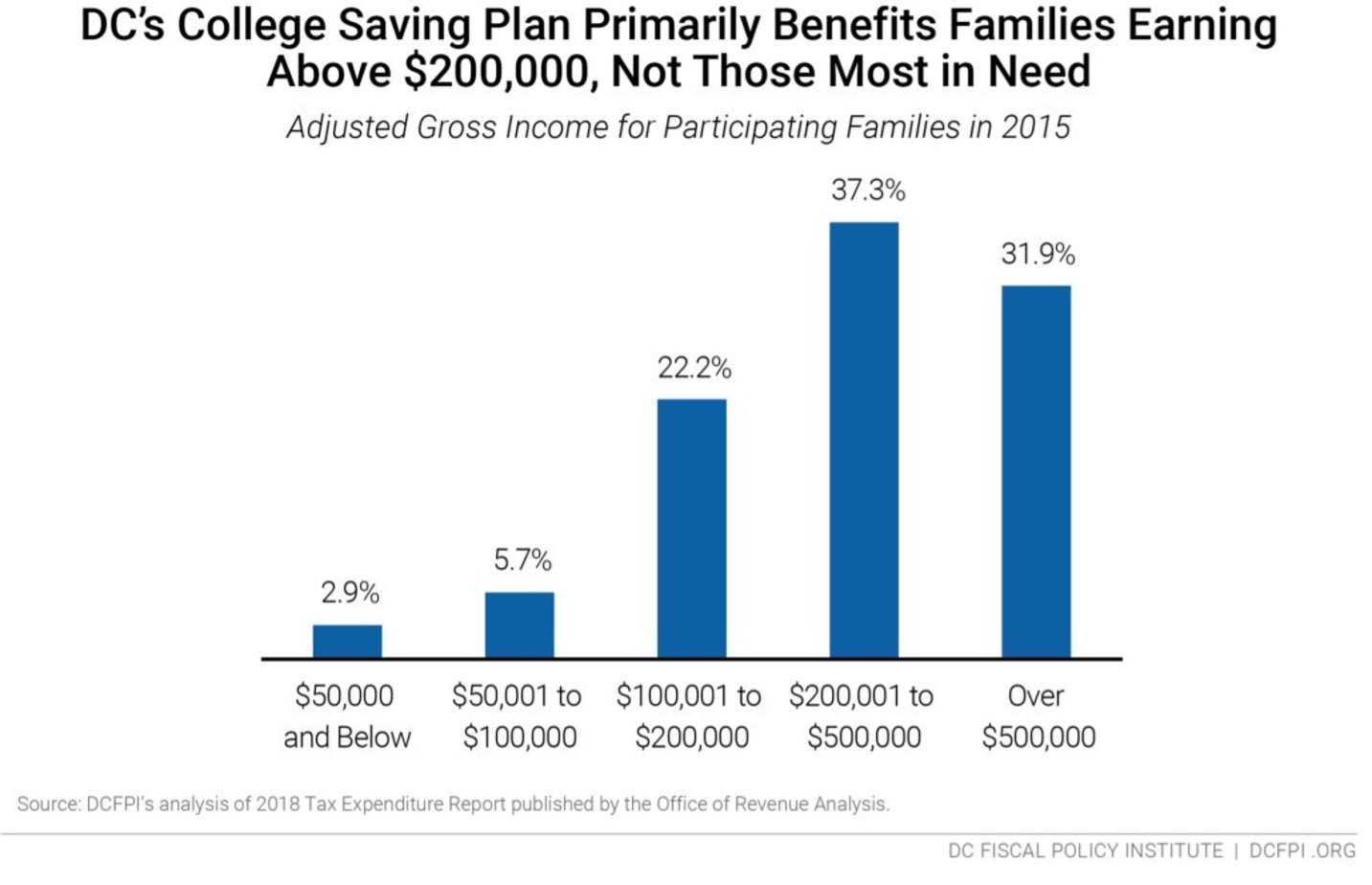

District lawmakers should consider repealing and replacing the DC College Savings Plan tax deduction, a deduction worth up to $8,000 for taxpayers making contributions to a college savings plan to pay for higher education expenses, such as tuition, fees, and books. This tax break, which costs $2.4 million annually, primarily benefits upper middle class and wealthy residents, while providing almost no benefit to lower-income families. More than 70 percent of the benefits flow to families making over $200,000 (see Figure below)—that is, families with disposable income who would likely save for their children’s future without a tax incentive receive this tax preference. Lawmakers could cap the income eligibility to target families who need it most and who might not otherwise be able to afford college. And they should ensure that the reformed deduction is big enough to make a difference for those who are struggling to pay for college.

Data and Process Improvements

Beyond tax changes, the DC Council should also require the Office of the Chief Financial Officer (OCFO) to track wealth data by race for District residents on a regular basis. The OCFO should collaborate with the newly formed Commission on Racial Equity, thanks to Councilmember McDuffie’s initiative to legislate the REACH Act. More data will enable DC policymakers to assess wealth concentration by wealth and tax solutions to build wealth equity across the city.

While DCFPI appreciates the opportunity to testify at today’s hearing, we strongly encourage the DC Council to hold an official, stand-alone public hearing on revenue as part of the budget process in order to discuss equity-oriented reforms to the tax code and to receive public testimony on those potential changes.

Conclusion: Tax Justice is the Solution

Raising revenue through taxes on the wealthiest would move everyone forward and enable DC to finally tackle some of its deepest inequities—in wealth, education, and housing in particular. Robust, sustained investments in people and families that help eliminate racial and economic inequities would boost economic opportunity and growth over the long-term. Furthermore, basing the tax code on one’s ability to pay would acknowledge and counteract through the tax system the structural barriers that leave Black and brown people overrepresented among households with low- and moderate-incomes and with the least wealth.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify.

[1] Michael Leachman et. al, “Advancing Racial Equity With State Tax Policy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 15, 2018.

[2] Similar data by wealth is not available. .

[3] Kiolo Kijakazi et. al, “The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital,” the Urban Institute, November 1, 2016.

[4] Data is not available at the DC level.

[5] For a historical review of racialized tax codes, see: Michael Leachman et. al, “Advancing Racial Equity With State Tax Policy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 15, 2018.

[6] Dean Obeidallah, “Are Taxes Racist? Author Dorothy Brown on How the Tax Code Makes the Wealth Gap Worse,” the Salon, May 5, 2021.

[7] Dorothy Brown, “Your Home’s Value is Based on Racism,” NY Times, March 20, 2021.

[8] Kasey Hendricks and Louise Seamster, “Mechanisms of the Racial Tax State,” Journal of Critical Sociology, October 11, 2016.

[9] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, update to Who Pays?, 6th edition, provided January 2021.

[10] Special data request to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 2021.

[11] DC Fiscal Policy Institute, “Revenue: Where DC Gets Its Money,” February 9, 2017.

[12] Ed Lazere, “DC Tax Commission Crunch Time,” DCFPI, December 5, 2013.

[13] Under current law, capital gains that people accrue over their lifetimes are simply erased when they die, so they don’t have to pay tax on capital gains income each year and neither they nor their heirs ever have to pay income tax on it. This is known as the “stepped-up basis” loophole. See this report on ways to reduce wealth concentration by ending this loophole, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/biden-proposals-would-reduce-large-tax-advantages-for-those-at-the-top-address

[14] Kiolo Kijakazi et. al, “The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital,” the Urban Institute, November 1, 2016.

[15] DCFPI’s analysis of American Community Survey data.

[16] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, update to Who Pays?, 6th edition, provided January 2021.

[17] Office of Chief Financial Officer’s 2020 Tax Expenditure Report.

[18] Claire Zippel, “The Mortgage Interest Deduction Mostly Benefits DC’s Highest-Income Residents,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, August 1, 2017.