Chairman Mendelson and members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to speak today. My name is Ed Lazere, and I am the Executive Director of the DC Fiscal Policy Institute. DCFPI promotes budget and policy choices to expand economic opportunity for DC residents and reduce income inequality in the District of Columbia, through independent research and policy recommendations.

I would like to offer several comments on Chairman Mendelson’s proposal to revise various elements of the Universal Paid Leave Act; these revisions were proposed largely with the goal of reducing expected expenses and keeping the costs of a paid family leave program within the revenue that would be generated by bill’s proposed financing structure. I also would like to comment on remarks made by some opponents of the legislation, who are concerned that paid family leave would because the tax paid by employers it would add to other recent requirements placed on them, including minimum wage increases. Those opponents suggest that there are signs that DC’s minimum wage increases have had negative effects on employment, yet recent employment growth in DC in industries dominated by minimum wage jobs provides no clear indication of negative employment effects. In fact, employment in those industries grew solidly in the year following the first step of the recent minimum wage increase, and faster than in the rest of the metro area.

I commend the efforts of Chairman Mendelson to amend the paid family leave program to ensure that it is fiscally responsible while also providing meaningful benefits. It is incredibly important that the costs of promised benefits of a new program fit within the revenue that would be raised for the paid family leave fund.

I have several comments on the chairman’s new proposal.

- The wage replacement rate for low-wage workers should not drop below 90 percent. DCFPI supports the proposal to reduce the wage replacement rate from 100 percent to 90 percent for the lowest-wage workers. But we would not support any further reduction. Many low-wage workers already find themselves behind on their bills and must juggle expenses each month to meet needs such as rent, utilities, and food. A 90 percent wage replacement rate when workers take needed leave will create an even larger gap between their incomes and expenses. If the replacement rate were lowered further, many low-wage workers would not be able to afford taking time off and thus would not have real access to paid family leave.

- Workers should be eligible after 6 months on the job, not 12: The Universal Paid Leave Act would allow workers to use paid family leave if they have worked for 6 months, but the Chairman’s proposal would shift that to 12 months. DCFPI recommends maintaining the original 6-month time frame to ensure that low-wage workers can access leave when needed. Many low-wage industries, such as retail, have high rates of employee turnover. Low-wage workers in these industries may maintain steady employment but switch employers on a more frequent basis than workers in other industries. A 12-month waiting period would prevent many workers, especially low-wage workers, from being able to access paid family leave, running counter to the clear intention of the bill to ensure that all workers will be able to participate.

- Paid Family Leave should include as many DC residents as possible: The chairman’s proposal would limit paid family leave to people working for private businesses in DC. Residents who work outside of the District or for the District or federal government would not be eligible. This means that an estimated 40 percent of residents would be unable to access paid family leave benefits that would be beneficial to them and their families. Including these residents in the paid family leave program would broaden the base of participants, which should reduce the risk of fund volatility, in addition to ensuring that all DC residents have access to this important benefit.

- Raise benefits over time if possible: It makes sense for the Council to develop a paid family leave program in a cautious way to ensure that revenues are adequate to pay for expected benefits. This means that the fund will effectively be designed to run a surplus in its early years. If the fund appears to be running a regular surplus, the Council should revisit the program’s design in ways that expand benefits, including increasing the maximum length of assistance from the 12 weeks proposed by Chairman Mendelson to the 16 weeks in the original legislation (or as close to 16 weeks as is feasible). The Council should not use evidence of a surplus to reduce the taxes that support the fund.

I also would like to address a claim made by some opponents of the legislation that DC’s recent minimum wage increase is negatively affecting employment growth in the District, and thus that the District should not place a new tax on employers to fund a paid family leave program. The DC Fiscal Policy Institute’s review of employment data shows that employment growth in the District in minimum-wage dominated industries was robust in the year following the July 1, 2014 minimum wage increase to $9.50 an hour.

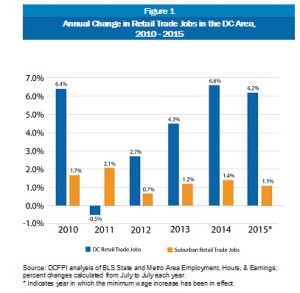

- Retail trade jobs in DC grew by 6.6 percent from July 2013 to July 2014, before the first phase of the minimum wage increase, and roughly the same — 2 percent — from July 2014 to July 2015, after the increase.

- Employment in DC’s limited-service eating places jobs grew only 1.1 percent from mid-2013 to mid-2014, and then grew by a much more robust 6.1 percent in the following year, which was the first full year of the wage increase.

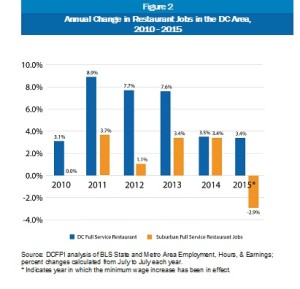

- Full-service restaurant jobs have shown extremely strong growth since 2011. In the two most recent years, growth slowed a bit, but still showed a robust 3.5 percent increase in 2014 and 3.4 percent in 2015.

Another way to assess an industry’s strength in DC is to compare its growth to that of surrounding suburbs. The District outpaced the suburbs in employment growth in both retail trade and restaurants in 2015, after the minimum wage increase, continuing a trend of higher growth in recent years. (This analysis compares DC with the remainder of the DC Metropolitan Division, [1] which includes suburbs in Maryland and Virginia).

- Retail: Job growth in DC’s retail sector has generally outperformed the area’s suburbs since 2010, especially in the last two years. Retail jobs in the District increased by 6.6 percent in 2014, before the minimum wage increase, compared with 1.4 percent in the rest of the Metro area. In 2015, after the DC minimum wage increase, retail employment grew 6.2 percent in DC, compared with just 1.1 percent in the suburbs. See Figure 1.

- Restaurants: The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides metro-level data on full-service restaurants, but not on limited

-service eating places (which would tend to employ more minimum wage workers). Nevertheless, a comparison of full-service restaurant jobs in DC and the rest of the metro area shows consistently stronger growth in the District than in the suburbs in every year in the last decade, except for 2014, when growth was about equal. [2] From July 2014 to July 2015, the first year after DC’s minimum wage increase, DC’s restaurants continued to add workers while suburban restaurants were shrinking. In that year, DC’s full-service restaurant jobs grew by 3.4 percent, while jobs in the suburbs actually declined by nearly 3 percent. See Figure 2.

-service eating places (which would tend to employ more minimum wage workers). Nevertheless, a comparison of full-service restaurant jobs in DC and the rest of the metro area shows consistently stronger growth in the District than in the suburbs in every year in the last decade, except for 2014, when growth was about equal. [2] From July 2014 to July 2015, the first year after DC’s minimum wage increase, DC’s restaurants continued to add workers while suburban restaurants were shrinking. In that year, DC’s full-service restaurant jobs grew by 3.4 percent, while jobs in the suburbs actually declined by nearly 3 percent. See Figure 2.

These figures suggest that the District economy was strong enough to absorb the July 2014 minimum wage increase, though they do not prove definitively that DC’s minimum wage increase is not having an effect on employment. This is in part because the data only reflect the first step of a three-step increase. Nevertheless, these figures challenge the notion made by opponents of the Universal Paid Family Leave Act that the minimum wage increase is hurting job growth in the District.

Thank you again for the opportunity to testify. I am happy to answer any questions.

[1] For a full list of counties included in the DC Metropolitan Division, visit: http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/msa_def.htm#47894

[2] This analysis highlights changes in fast food restaurants (“limited service eating places”), because they are the restaurants most likely to have hourly workers at the $9.50 minimum wage. (Other areas of the restaurant industry, such as restaurants and bars, employ many workers who are tipped, and therefore do not make the regular minimum wage.) However, the BLS does not break out data on limited service eating places for the DC metro area. So, in order to compare restaurant industry employment trends across jurisdictions, this analysis examines data on full-service restaurants. An analysis by the American Enterprise Institute focused on an even broader category of “food service and drinking places” to assess the minimum wage impact. However, this broader category includes even more employees who do not make the regular minimum wage, and thus is not an ideal way to assess the minimum wage impact. AEI also did not analyze retail employment, even though it is an industry with a substantial number of minimum wage workers.