Chairman Mendelson and members of the Committee of the Whole, thank you for the opportunity to speak today. My name is Ed Lazere, and I am the Executive Director of the DC Fiscal Policy Institute. DCFPI is a non-profit organization that promotes budget and policy choices to expand economic opportunity for DC residents and reduce income inequality in the District of Columbia.

I am here to speak in support of Bill 21-415 and the effort to create a universal paid family leave insurance program in the District. By helping DC residents balance work and family life, by supporting stable family incomes after the birth of a child or during a serious illness, and by ensuring that workers who take time off for these reasons can return to their jobs, paid family leave will be good for DC’s families and good for the DC economy.

The lack of access to paid family leave has negative effects on the employment and earnings of those who need to take leave, which in turn has a negative effect on the economy. Workers with paid family leave are more likely to return to the same employer than those without, a benefit to both workers and their employers. Women who take maternity leave are more likely to return to the labor market, to stay with the same employer, and to maintain their wages if they have paid leave. In other words, it is likely that more women will be working, and at higher wages, if the District adopts paid family leave. This is important, given that women in DC typically earn less than men and are less likely to be in the labor market. Paid family leave could lead to 6,500 more women working in DC.

Paid family leave will be particularly beneficial to low-income families. DCFPI estimates that each year 31,000 DC workers who need to take leave do not do so, and that nearly half of those — 14,300 workers — don’t take leave because they can’t afford to do so without pay[i] .

Beyond that, paid family leave will help the many low-wage workers who now take leave to be with a child or ill relative, even though that means going without pay and risking their jobs. Paid family leave thus will help many residents maintain their jobs and incomes, helping them survive in DC’s increasingly challenging economy. Many low-wage workers face flat or falling wages and high unemployment years into an economic expansion, yet housing costs that have risen to very high levels. The low incomes of many DC residents stem in part from breaks in employment and difficulties getting back to work after being unemployed; leaving work to address family needs is no doubt a major cause of breaks in employment. Policies like paid family leave that stabilize will not only help working DC residents keep their jobs and keep up with the rising cost of living in DC. Paid family leave also will help families avoid the kinds of stresses that research shows can be devastating to the development of young children.

It also is important to note that I am a small business employer who has not been able to provide paid family leave to my employees. If a DC paid family leave insurance program ends up requiring a contribution of up to one percent of payroll, I would contribute roughly $5,000 of my $850,000 in expenses, a relatively modest amount in return for a benefit that allows me to attract and retain good workers.

Paid Family Leave Will Help Offset Falling Wages and High Unemployment Faced by Many DC Residents

The DC economy is in many ways very strong, yet it poses serious and growing challenges for low-wage workers. Paid family leave will help offset economic trends that have left many workers with stagnant or falling earnings. It also will help workers avoid losing their job at a time when unemployment is high among Black residents and residents without a college degree.

- Long-term growth in wage disparities: Over the last 35 years, wages have grown just about 2 cents an hour, after inflation, for the bottom 20 percent of working DC residents. These workers earn about $12 an hour, far below a living wage. Meanwhile, wages have grown by 50 percent for the highest paid workers.[ii]

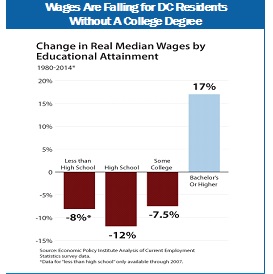

- Recent wage collapse for workers without a college degree: Since 2007, the typical DC resident with a high school degree saw her hourly pay drop $2 an hour after adjusting for inflation. These are not necessarily cuts in pay for ongoing job, but are likely to include workers who lost a job and could not find a new job at the same wage.[iii]

- Stubbornly high unemployment since the recession: One-third of DC residents with a high school degree are either unemployed, working part-time despite wanting full-time hours, or too discouraged to look for work. The unemployment rate today for high school graduates is higher today than since the start of the Great Recession, meaning that the economy has not fully recovered for these workers.[iv]

- Longer periods of unemployment: Today, nearly half of workers who lose their jobs stay unemployed more than 6 months. This compares with one-fifth of workers who took this long to find a new job in 2007.[v]

These employment challenges are especially significant for Black and Latino residents, who are much likely to be unemployed and to stay out of work for an extended period when they lose a job. High unemployment among Black and Latino residents partly reflects lower educational levels but also employment discrimination. Some 16 percent of Black DC residents are unemployed, compared with 6 percent of Latino residents and under 3 percent of white residents.[vi]

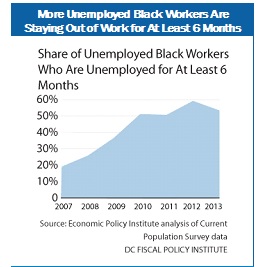

Beyond that, Black workers increasingly stay unemployed for an extended period of time, and are far more likely to do so than white workers. In 2012, more than half of Black workers who lost their job stayed out of work more than six months, compared with three in 10 white unemployed workers.[vii]

Paid Family Leave Will Reduce Poverty and Income Inequality

The disparities in employment and wages between college-educated and other residents contributes to DC’s very high income inequality, and to a level of poverty that has not recovered from a spike during the Great Recession. A paid family leave insurance program would help offset these trends.

- Wide Income Gaps: The average income of the poorest fifth of DC households is under $10,000. Meanwhile the top 5 percent of DC households have incomes over half a million, the highest among major U.S. cities. As a result, income inequality in the District is fourth widest among major U.S. cities.[viii]

- Significant Poverty Years into an Economic Recovery: Some 110,000 DC residents live in poverty, or less than $20,000 for a family of three. The number of poor residents is 18,000 higher than in 2007, just before the Great Recession.[ix]

- Very High Child Poverty: Poverty is especially high among children, particularly east of the Anacostia River. Half of children east of the river lived in poverty in 2014.

Not surprisingly, workers who have paid family leave are less likely to rely on public assistance than those who do not.[x] In DC, DCFPI estimates that there would be 2,400 fewer families who received food stamps and/or cash assistance at any time during a leave.[xi] This is a further sign that paid family leave supports family incomes and reduces poverty in a meaningful way.

Paid Family Leave Will Help DC Residents Keep Up with Rising Housing Costs

Sharply rising rents in the District have led to the virtual disappearance of low-cost private housing across the city. Combined with stagnant incomes for nearly half of DC residents, a growing number of households are forced to spend the majority of their income on rent and utilities, struggling each month to maintain stable housing and afford other necessities like food and transportation. Paid family leave will help residents cope with these housing price pressures.[xii]

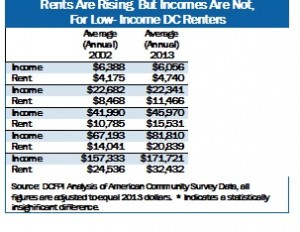

Rents in DC have risen across the board, for residents seeking a low-cost basement rental to those looking for a luxury apartment or home. But the impacts have been greatest for lower-income residents, whose incomes have not grown as a result of the wage and unemployment trends discussed below. Household incomes have not grown at all in the past decade, beyond inflation, for the poorest two-fifths of renter households. For example, DC households with incomes of roughly $1,900 a month have seen rents rise $250 a month in the past decade, to roughly $1,000 per month, with no corresponding increase in income. For these households, the typical rent now exceeds half of their income.

The lack of affordable housing affects the ability of residents to thrive and the city to remain economically strong. Families that spend the majority of their limited budget on housing costs are forced to cut other necessities like food, health care, and transportation. The high cost of housing leads families to live in substandard housing, with problems like mold or rodents, and forces many to move frequently. Unstable and unhealthy housing puts stress on families that makes it hard for children to focus at school and for parents to keep a job, and leaves many at risk of homelessness.

Paid Family Leave Would Help the DC Economy, Especially Working Women

The lack of access to paid family leave has negative effects on the employment and earnings of those who need to take leave, which in turn has a negative effect on the economy.

- Reduced Turnover: Workers with paid family leave are more likely to return to the same employer than those without, a benefit to both workers and their employers. Workers who re-enter the labor force after a family leave are 9 percentage points more likely to return to the same employer if the leave was paid than if it was unpaid.[xiii] In DC, access to paid family leave would increase the number of workers returning to the same employer after leave by 7,200.[xiv] Turnover costs typically range from 20 percent to 150 percent of the employee’s salary.[xv]

- Increased Employment for Women after Having a Child: Women who take maternity leave are more likely to return to the labor market, to stay with the same employer, and to maintain their wages if they have paid leave. Paid family leave in California was responsible for an estimated 10 percentage point increase in the probability a mother who worked at some point during her pregnancy is still working a year after the birth.[xvi]

- Better Wages for Women: Because paid leave helps mothers to stay in the labor force and increases the probability they’ll be working for the same employer when they return from leave, it decreases the risk of lost work experience and seniority at the employer. Other research bears out this hypothesis: one-third of the “motherhood wage penalty” — the decline in wages that women typically experience after having children — is explained by lost experience and seniority due to employment disruptions.[xvii]

- More Working Women: Paid family leave programs increase the labor force participation of women. Based on research in other communities, DCFPI estimates that paid family leave could 6,500 more women remain in the labor force.[xviii]

In other words, it is likely that more women will be working, and at higher wages, if the District adopts paid family leave. This is important, given that women in DC typically earn less than men — the median annual earnings of women are $5,800 lower than for men. [xix] In addition 79 percent of working-age women in DC are in the labor market, compared with 84 percent of men. [xx]

Paid Family Leave Promotes Financial Stability for Low-Wage Workers and Their Families

These findings highlight the importance of helping DC workers keep their jobs, especially those without a college degree and those who are financially vulnerable, through paid family leave and other policies. Unemployment can occur when workers face the choice between taking time to be with a new baby or an ill family member or keep their job. Many make the understandable choice to be with their family but then face a break in income or even loss of their job to do so. Paid family leave thus is important not only so that parents can be with a newborn or ill relative, but also to maintaining the employment and economic stability of a large number of families in the District who face these choices on a regular basis.

A large and growing body of research finds that family economic stability — or the lack thereof — can have lasting impacts on a child’s ability to succeed in school and in later life. The challenges poor parents face in creating a nurturing environment for their children — poor nutrition, unstable and unhealthy housing, and exposure to violence — have adverse impacts on the physical and cognitive development of children, including impacts on brain development of very young children. Children who live in poverty have worse outcomes in a range of areas including: physical and mental health, cognitive development, school achievement and emotional well-being. They score lower on academic tests, complete fewer years of education, work less, and earn less than others.[xxi] This means that economic instability harmful to families and children, and in turn to the future of DC’s economy.

By helping workers keep their jobs and avoid long periods without pay, paid family leave can help address DC’s wide income inequality and keep families from falling into poverty. Stabilizing employment and incomes as residents go through normal life experiences that require a leave from work is critical to helping residents keep their jobs, keep up with rising rents, and maintaining a home where children can thrive.

DC Fiscal Policy Institute’s Perspective on Paid Family Leave as an Employer

The DC Fiscal Policy Institute is a small business employer in DC that would be affected by this legislation. We currently provide temporary disability insurance for up to 6 weeks, including to women who take time off after the birth of a child. A paid family leave insurance program would allow us to expand employee benefits and retain talented staff at a relatively modest cost.

DCFPI has a staff and annual expenses of about $850,000, of which roughly $500,000 is for salaries. A DC paid family leave insurance program requiring a contribution of up to one percent of payroll would cost DCFPI about $5,000, or about 0.6 percent of overall expenses. I view this as a relatively modest amount in return for a benefit that allows me to attract and retain good workers. As a nonprofit that is not able to pay salaries that compete with DC government or with for-profit employers, fringe benefits that support work-life balance are very important.

I currently am experiencing the impact of leave on my staffing, with an employee who is in the midst of taking 16 weeks of maternity leave (most of it unpaid). This has no doubt increased my workload and that of other staff members, but we have managed to maintain all of our projects. It reminds me of the experience of my father, who owned a retail bakery. My dad often had to put in extra time when he lost a talented staff member temporarily or permanently — a bread baker or cake decorator, for example. He did not complain — much — because he understood that is how life goes as a small business owner. I share his perspective: policies that allow my staff to take the time they need to be with a new child or an ill relative undoubtedly add to my workload and that of other staff, but it is simply something we do as part of a workplace that supports our employees and that we know will support us when a similar need arises.

To print a copy of today’s testimony, click here.

[i] DCFPI estimate based on: Rate of unmet need for leave for US workers; Percent of workers with unmet need for leave who said they could not afford to take an unpaid leave: Abt Associates for US Department of Labor, “Family and Medical Leave in 2012: Technical Report,” Apr. 2014. Number of DC workers: State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates for the District of Columbia, US Department of Labor, May 2014.

[ii] DC Fiscal Policy Institute, Left Behind: DC’s Economic Recovery Is Not Reaching All Residents, January 29, 2015, page 2

[iii] DC Fiscal Policy Institute, Two Paths to Better Jobs for DC Residents, October 15, 2015, page 4.

[iv] DC Fiscal Policy Institute, Left Behind: DC’s Economic Recovery Is Not Reaching All Residents, op cit, page 3.

[v] Ibid, page 4.

[vi] Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data.

[vii] DC Fiscal Policy Institute, Left Behind: DC’s Economic Recovery Is Not Reaching All Residents, op cit, page 4

[viii] DC Fiscal Policy Institute, High and Wide: Income Inequality Gap in the District One of the Biggest in the U.S., March 20, 2014.

[ix] DC Fiscal Policy Institute, While DC Continues to Recover from the Recession, Communities of Color Continue to Face Challenges, September 18, 2015.

[x] Arindrajit Dube and Ethan Kaplan, “Paid Family Leave in California: An Analysis of Costs and Benefits,” Labor Project for Working Families, Jun. 2002.

[xi] DCFPI estimate based on: Number of DC workers: State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates for the District of Columbia, US Department of Labor, May 2014. Percent of US workers who take unpaid family leave in a given year: Arindrajit Dube and Ethan Kaplan, “Paid Family Leave in California: An Analysis of Costs and Benefits,” Labor Project for Working Families, Jun. 2002. Regression-adjusted differential probability of US worker receiving public assistance at any time while on leave (paid – unpaid leave): Arindrajit Dube and Ethan Kaplan, “Paid Family Leave in California: An Analysis of Costs and Benefits,” Labor Project for Working Families, Jun. 2002.

[xii] The figures in this section are from DC Fiscal Policy Institute, Going Going Gone: DC’s Vanishing Affordable Housing, March 2015.

[xiii] Arindrajit Dube and Ethan Kaplan, “Paid Family Leave in California: An Analysis of Costs and Benefits,” Labor Project for Working Families, Jun. 2002.

[xiv] DCFPI estimate based on: Regression-adjusted differential probability of return (paid – unpaid leave): Arindrajit Dube and Ethan Kaplan, “Paid Family Leave in California: An Analysis of Costs and Benefits,” Labor Project for Working Families, Jun. 2002. Percent of US workers who took leave in past 12 months: Abt Associates for US Department of Labor, “Family and Medical Leave in 2012: Technical Report,” Apr. 2014. Percent of US workers with access to paid family leave: National Compensation Survey, US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015. Number of DC workers: State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates for the District of Columbia, US Department of Labor, May 2014.

[xv] Laurie Bassi and Dan McMurrer, “Professional Employer Organizations: Keeping Turnover Low and Survival High,” National Association of Professional Employer Organizations, Sept. 2014. Heather Boushey and Sarah Jane Glynn, Center for American Progress, “There Are Significant Business Costs to Replacing Employees,” Nov. 2012.

[xvi] Baseline mean return-to-work rate was 81.3 percent. Charles L. Baum and Christopher J. Ruhm, “The Effects of Paid Family Leave in California on Labor Market Outcomes,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 19741, Dec. 2013.

[xvii] Michelle J. Budig and Paula England, “The Wage Penalty for Motherhood,” American Sociological Review, Vol. 66, Apr. 2001.

[xviii] DCFPI estimate based on: DC labor force participation rate, working-age (25 to 64) men; DC labor force participation rate, working-age (25 to 64) women; Women as a percent of DC workforce: Claudia Williams, Washington Area Women’s Foundation, “Investing in Change: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities for Women in the Washington Region’s Labor Force,” Sept. 2015. Number of DC workers: State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates for the District of Columbia, US Department of Labor, May 2014. Estimated increase in US women’s labor force participation if the US had family-friendly workplace policies like its OECD peers: Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn, “Female Labor Supply: Why Is the United States Falling Behind?” American Economic Review, Vol. 103.3, May 2013.

[xix] Claudia Williams, Washington Area Women’s Foundation, “Investing in Change: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities for Women in the Washington Region’s Labor Force,” Sept. 2015.

[xx] Working age is defined as 25 to 64. Claudia Williams, Washington Area Women’s Foundation, “Investing in Change: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities for Women in the Washington Region’s Labor Force,” Sep. 2015.

[xxi] “The Long Reach of Early Childhood Poverty” Greg Duncan & Katherine Magnuson, Pathways, Winter 2011.