Chairperson Mendelson, members of the Committee, and Committee staff, thank you for the opportunity to testify. My name is Qubilah Huddleston, and I am a Policy Analyst at the DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI). DCFPI is a non-profit organization that shapes racially-just tax, budget, and policy decisions by centering Black and brown communities in our research and analysis, community partnerships, and advocacy efforts to advance an antiracist, equitable future.

I would like to focus my testimony on the fiscal year (FY) 2023 Proposed Budget for DC Public Schools (DCPS). My testimony focuses on DCFPI’s analysis of schools’ initial budgets with some reference to their submitted budgets.

DCPS has launched a new school budget model for School Year 2022-23 that is designed to bring more transparency, equity, and stability to school budgets. Additionally, the Mayor proposed a 5.87 percent increase (unadjusted for inflation) to the per-pupil base of the Uniform Per Student Funding Formula (UPSFF) and a suite of funds to stabilize school budgets that would otherwise decrease significantly due to enrollment declines. These changes are welcome, but they alone may not be enough to stabilize schools’ budgets, now or in the future. In addition, these changes may fail to usher in long overdue structural changes that could provide adequate and equitable resources to Black and brown students, students from families with low incomes, and other students facing barriers to learning through no fault of their own.[1]

To put the District on a path toward better educational adequacy and equity, and for policymakers to keep and build on the promises they made in FY 2022 to meet the educational and socio-emotional needs of students—one of several sound steps for sustaining an equitable recovery from the pandemic[2]—DCFPI urges the Mayor, DC Council, and top education officials to:

- Develop a plan to help schools avoid “fiscal cliffs” in FY 2024 and beyond.

- Ensure that schools have enough local, recurring dollars to cover rising costs in perpetuity.

- Ensure that schools do not lose staff positions in a manner that is disproportionate to grade level projected enrollment declines.

- Add a small school supplemental weight to DCPS’ new budgeting model to ensure that schools with declining enrollment can afford general education services without having to supplant “at-risk” funds. And,

- Create and enforce a District-wide, multi-year education vision that ensures every ward has a high quality, adequately funded neighborhood school.

DCPS Should Develop a Plan to Prevent School Budget “Fiscal Cliffs” Due to One-Time Funds

More than half of the schools within DCPS have FY 2023 initial budgets that are lower than their FY 2022 budgets that were boosted by federal funds, based on our analysis.[3] This school year, many DCPS schools are relying on one-time Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) and other one-time funds to cover costs of classroom teachers, aides, and other key general education positions. Consequently, some schools are facing potential fiscal cliffs where they are funding recurring expenses with one-time dollars that will disappear at the end of FY 2024. DCPS should develop a plan to prevent school budget “fiscal cliffs” in the financial plan.

The FY 2022 Approved Budget allocated $40.3 million in one-time dollars, including ESSER and local stabilization dollars. Seventy-five percent of these funds consists of ESSER II and ESSER III while the remaining 25 percent consists of local stabilization dollars. For FY 2023, DCPS did not originally included ESSER III funds in schools’ initial budgets. However, the FY 2023 submitted budgets show that DCPS has given some schools ESSER funds.[4] For FY 2023, the Mayor is proposing a total of $43.1 million in stability funds for DCPS with a little more than half consisting of the Mayor’s one-time Recovery Funds, or pandemic supplement, and Hold Harmless Funds. The other half consists of Safety Net and Stabilization Funds that DCPS provides to schools per its new school budget model and a DC law that requires DCPS to give schools at least 95 percent of their prior year budget.[5]

The Deputy Mayor’s for Education Office has shared with DCFPI that the Mayor will provide the pandemic supplement to DCPS and public charter schools in FYs 2023 and 2024. This is good news, and the Mayor is right to provide schools with stabilization funds as many schools, especially DCPS elementary schools and schools in Wards 4, 7, and 8, are projected to experience significant enrollment declines that will drive funding losses. However, with the uncertainty of COVID-19 and its harm on student enrollment and student needs, DCPS should develop a plan to ensure that schools local budgets are sufficient during COVID-19 and beyond to avoid a fiscal cliff. While recovery funds may be one-time, student needs are not.

District Leaders Must Ensure that the DCPS Budget Keeps Up with Rising Costs and DCPS Adjusts School Budgets Accordingly, Now and Beyond

District leaders’ failure to ensure that DCPS’ budget keeps up with real costs is an ongoing issue that will take sound policy choices and improved budgeting practices. DCFPI and other advocates have repeatedly highlighted how bad budgeting practices undermine adequately funded school budgets. These practices include the Office of Chief Financial Officer’s failure to prepare a Current Services Funding Level budget for DCPS and the public charters and the Mayor basing her proposed increases to UPSFF on the District’s revenue and other local priorities instead of actual costs to operate the two systems.

For FY 2023, the Mayor is proposing a 5.87 percent increase (unadjusted for inflation) to the per-pupil base of the UPSFF. This would increase the per-pupil base to $12,419 from $11,730 over the FY 2022 Approved Budget.[6] Adjusted for inflation, DCPS’ general fund budget would grow by 7 percent, or $68.7 million, driven by the UPSFF increase, funding for IMPACT bonuses, local stabilization funds, funding for Early Stages, and the pandemic supplement.

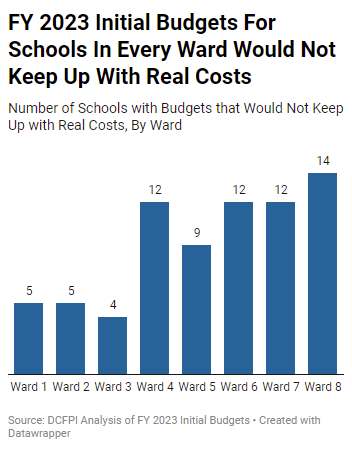

DCFPI and other advocates have regularly testified to urge the Mayor and Council to provide adequate increases to the per-pupil base of the UPSFF—namely increases that meet the recommended adequacy level in the 2013 DC Adequacy Study and keep up with real costs. However, according to our analysis, 73 schools have FY 2023 initial budgets that would not keep up with FY 2023 costs—a combination of staffing costs which DCPS itself itemizes and non-personnel services (NPS) that DCFPI adjusted for inflation.[7] Schools with budgets that would not keep up with FY 2023 costs and inflation are concentrated in Wards 4, 6, 7, and 8, although there are schools in every ward that have FY 2023 initial budgets that would not keep up (Figure 1). The average gap for the inability to keep up with FY 2023 costs across the 73 schools is nearly $270,000.

DCFPI and other advocates have regularly testified to urge the Mayor and Council to provide adequate increases to the per-pupil base of the UPSFF—namely increases that meet the recommended adequacy level in the 2013 DC Adequacy Study and keep up with real costs. However, according to our analysis, 73 schools have FY 2023 initial budgets that would not keep up with FY 2023 costs—a combination of staffing costs which DCPS itself itemizes and non-personnel services (NPS) that DCFPI adjusted for inflation.[7] Schools with budgets that would not keep up with FY 2023 costs and inflation are concentrated in Wards 4, 6, 7, and 8, although there are schools in every ward that have FY 2023 initial budgets that would not keep up (Figure 1). The average gap for the inability to keep up with FY 2023 costs across the 73 schools is nearly $270,000.

Although DCFPI hasn’t complete a full analysis of the FY 2023 submitted budgets, they show that DCPS provided additional funds over initial budgets to at least 23 schools. Nearly all the schools that DCPS gave additional funds received them to account for the lost buying power that schools would experience due to “new [special education] alignment plans.” These funds appear to be one-time dollars based on their description in the budget documents. Considering that schools will likely continue to offer these special education services beyond FY 2023, DCPS should have provided schools and others that may be losing buying power additional local, recurring dollars to close the gap.

DCFPI recognizes that schools’ needs can change from one year to the next. However, at a minimum, DCPS should ensure schools’ local, recurring funding keeps up with rising costs to provide schools with some sense of predictability and stability in their budgets—conditions that could improve teacher retention and attract families to schools. Schools, when adequately and predictably funded by policymakers, can and should be valuable community institutions that students and families can trust to educate the next generation of leaders in DC. Currently, there is pending legislation—introduced by Chairperson Mendelson—aimed at ending the “annual school budget crisis” of unstable and unpredictable initial school budgets. DCFPI looks forward to the DC Council collaborating with the Mayor and DCPS Chancellor to solve such crisis.

School Staff Losses Should Be Minimal, and if They Occur at All, Proportionate to Projected Grade Level Declines

The Mayor and DCPS Chancellor intend for the one-time pandemic supplement and Hold Harmless Funds to “ensure that no school receives less than their initial allocation last year and schools have more buying power for similar staff and programming from FY [2022].”[8] DCFPI attempted to compare FY 2022 staffing allocations to FY 2023 staffing allocations. However, due to some positions missing from the FY 2023 submitted budget documents, DCFPI is unable to determine the extent to which the Mayor and Chancellor are making good on their commitment. Notably, some school members have shared with DCFPI staff that they are losing needed positions in their FY 2023 budgets.

Schools generally risk losing staff positions due to enrollment declines. However, there have been fiscal years when the Deputy Mayor for Education did not project enrollment losses at some schools that still found themselves having to choose between equally important positions, namely due to the loss of buying power. Further, even for schools where enrollment is declining, that decline does not always result in a clear-cut change in staffing needs—other interlocking factors create complexity. For example, projected enrollment loss is often spread across grades, and relatedly, because the dollar loss in funding from enrollment declines is so great, schools can’t just trim around the edges. Instead, they are forced to cut whole positions within a specific grade level or cross-cutting roles that serve all students.

DCPS should ensure that schools do not lose staff disproportionate projected grade-level enrollment declines. This would help ensure that schools can have the academic and school support staff that they need.

District Leaders Should Create and Enforce a District-wide Education Vision That Protects Enrollment in Neighborhood Schools

Enrollment declines continue to hit DCPS schools in the District’s Blackest and brownest and lowest income communities the hardest, and the pandemic has only exacerbated this loss. Because schools’ budgets are primarily driven by enrollment, these declines undermine the very schools that already struggle to meet the needs of their students. While DCPS’ enrollment methodology attempts to keep school budgets whole amid enrollment losses, opportunities remain to protect neighborhood schools from funding losses due to student population decline.[9] For example, DCPS could explore the addition of a new weight to its funding model for schools with below average enrollments, whose funding is more sensitive to enrollment fluctuations. Addition of such a weight could especially help small schools by reducing their need to rely on their “at-risk” and other targeted support funding to cover basic educational costs.

Another major enrollment concern is a growing saturation of new charter schools, especially in Wards 5,7, and 8, without a proportionate growth in DC’s school-age population. This can lead to more families opting out of neighborhood schools and in turn, drive down DCPS enrollment.

The DC Public Charter School Board has authority to open to 10 new charter schools per year regardless of enrollment capacity needs. Considering enrollment at DCPS schools in Wards 5, 7, and 8 have only about 50 percent capacity due to school closures, charter growth without corresponding growth in the number of students will likely attract students away from DCPS neighborhood schools in these wards that have been historically underfunded.[10]

To protect against enrollment losses within DCPS, policymakers could require new charters to consider enrollment capacity needs and place a cap on the number of charter school openings, as many other states have done.[11] DCPS should also consider making stronger investments to improve existing, neighborhood schools in communities where poverty is concentrated before opening new schools. Opening new schools without strengthening existing schools further contributes to the diversion of resources for children from families with low incomes, their families, and their larger communities.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify, and I am happy to answer any questions.

[1] Qubilah Huddleston and Michael Johnson, “New DC Public Schools Budget Model Makes Progress Towards More Transparency and Flexibility, but Falls Short on Addressing Structural Funding Inadequacy and Inequity,” DCFPI, March 14, 2022.

[2] DC Fiscal Policy Institute, “Principles for Sustaining an Equitable Recovery,” DCFPI, February 8, 2022.

[3] Qubilah Huddleston and Michael Johnson.

[4] Due to how DCPS formatted the budget documents and accompanying Excel spreadsheet, DCFPI is unable to state the total amount of ESSER III funds that DCPS would provide to schools until further analysis

[5] DCPS Budget, D.C. Code §38-2907.01(2).

[6] Adjusted for inflation, the FY 2023 UPSFF per-pupil would increase by 3.5 percent over the FY 2022 Approved UPSFF per-pupil.

[7] DCFPI assumed FY 2022 approved personnel and non-personnel allocations to determine whether schools FY 2023 initial budgets would keep up with rising costs. DCFPI used this approach since DCPS’ new budget model only includes a limited number of pre-budgeted positions—a departure from DCPS’ Comprehensive Staffing Model. Read “New DC Public Schools Budget Model Makes Progress Towards More Transparency and Flexibility, but Falls Short on Addressing Structural Funding Inadequacy and Inequity” by Qubilah Huddleston and Michael Johnson for more information on our methodology.

[8] DCPS, “FY 2023 DCPS Budget Guide, Welcome and Introduction.”

[9] DCPS, “Enrollment Projection Methodology.”

[10] “C4DC Statement on Strengthening DCPS Education,” Coalition for DC Public Schools & Communities, March 2022

[11] Perry Stein, “More charter schools want to open in D.C., but how many can the city handle?”, The Washington Post, May 2019.