This report is part of a series of research and analysis on how DC can build a tax system that embodies racial justice in both its design and the public investments it provides. Find the full series here.

The supermajority of wealth in DC and the nation is concentrated in the hands of the few, with Black residents holding very little wealth compared to white residents. The concentration of white wealth stems from centuries of racist and extractive policies and practices that have systematically stripped Black people of wealth they produced while allowing white people to amass extreme wealth and grow it across generations. District policymakers can advance wealth equity by fixing our tax system, which rather than being a tool to reduce racial wealth inequities, protects and grows wealth concentration through myriad tax preferences and loopholes. Eliminating or limiting these preferences would make DC’s tax code more progressive and push back against economic inequality.

The federal and DC governments tax income from wealth more favorably than income from work. This preferential treatment means we under tax the most well-off, tax their wealth less often, and, in some cases, allow them to accumulate fortunes and pass vast sums of wealth to heirs tax-free. The favorable treatment of capital gains income—profits generated from wealth such as stocks and real estate—is particularly egregious and benefits white households the most. DC taxes capital gains income at the same rate as income from work, unlike the federal government, which taxes capital gains at a lower rate than income from work. DC, however, follows federal policy allowing the wealthy to defer paying taxes on appreciating assets for years and sometimes decades until they are sold and exempts a lifetime of untaxed capital gains income upon death, costing tens of millions a year. DC’s tax code also includes a bevy of other advantages for wealth.

This special tax treatment of capital gains income—which overwhelmingly flows to the top 1 percent—is part of why DC taxpayers in the top 20 percent, on average, have a lower effective tax rate than those in the middle of the income scale.[1] The inequitable tax treatment of investment income helps cement DC’s deep racial wealth divide, which is staggering: the median Black household in the DC area has under $4,000 in net assets—essentially no cushion to weather a crisis, like a pandemic—and the median white household has 81 times the wealth of the median Black household.[2] DC is also home to a disproportionate share of the nation’s ultra-wealthy, high-income filers who hoard nearly half of all DC’s wealth.[3]

Racial justice requires unrigging this system, and taxing wealth more heavily, to build a future of shared abundance. To do so, DC should consider:

- eliminating all local exclusions or deductions that reduce taxable capital gains income, except for the sale of a principal residence;

- raising the tax rate on capital gains income;

- eliminating the “stepped-up basis” for capital gains bequeathed at death; and,

- taxing gains as they are accrued, rather than as they are realized from the sale of the assets generating them.

These proposals could raise tens to hundreds of millions of dollars. By itself, no single one of these proposals would ensure that wealthy tax filers pay a fair amount of taxes. Together, however, they would represent a modest step in that direction and would enhance DC’s ability to invest in wealth-building and economic security programs for Black and brown communities.

Table of Contents

- Capital Gains Tax Breaks Grow Racial Disparities in Wealth, Income

- The US Tax Code Favors Capital Gains, At Great Cost

- How DC Treats Capital Gains

- Strengthening DC’ Capital Gains Taxes Can Help Close the Racial Wealth Gap and Raise Revenue

“Tax Flight” is a Myth: DC Should Tax Wealth More Heavily to Build a Future of Shared

Progressive state taxes do not lead to a meaningful level of “tax flight” among top earners, evidence shows. A groundbreaking study by Cristobal Young on taxes and millionaire migration—which examined the tax returns for every household reporting income of at least $1 million between 1999 and 2011—fully debunks the notion that millionaires flee en masse from higher- to lower-tax states.[4] In fact, millionaires have a slightly lower migration rate (2.4 percent) than the general population (2.9 percent). In a given year, just 0.3 percent of all US millionaires are motivated to move to another state for lower taxes. And if millionaires who move to Florida were excluded, that rate would drop to roughly 0.07 percent, based on the DC Fiscal Policy Institute’s analysis of Young’s data.[5]

Young recently updated his analysis with 2016 to 2019 data, with his main findings largely staying the same. The rate of millionaire migration was unchanged, but the millionaires who did move were more likely to move to states with lower-than-average taxes.[6] During this period, Congress approved the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which capped the deductibility of state and local taxes, affecting millionaires residing in higher tax states the most. While the TCJA didn’t increase migration, it made lower tax states more attractive for millionaires who moved.[7] And while most millionaires are highly tied to their place of residence for socio-economic reasons—such as marriage and business ownership—further research by Young found the pandemic somewhat weakened millionaires’ attachment to place, demonstrating that large shocks can affect migration.[8]

Young’s research also shows that the magnitude of the effects of taxes on migration would need to be 8 to 15 times higher for it to be a relevant consideration in tax policy decisions. In fact, the combined federal and state top marginal income tax rate needs to reach 68 percent to induce a problematic level of millionaire tax flight.[9] The current combined federal and DC top marginal income tax rate is 47.75 percent, giving lawmakers plenty of room to improve its capital gains tax. Moreover, because of the small number of millionaires who move based on taxes, revenue raised through a tax increase on millionaires would exceed any revenue loss from those moves.

Similarly, little credible evidence supports the claim that wealth taxes such as an estate or inheritance tax harms a state’s economy by causing large numbers of elderly people to leave the state or by discouraging them from moving there. At most, academic studies find that these taxes have a small effect on the residence decisions of a few, very wealthy elderly people.[10]

For years, the tax flight myth has survived based on cherry-picked anecdotes of millionaires moving—or sometimes threatening to move—due to claims of high taxes. Instead of catering to unfounded anecdotes and ginned-up concerns, DC should structure its tax system in a way that raises the shared resources needed to build widespread prosperity and thriving, equitable communities.

Capital Gains Tax Breaks Grow Racial Disparities in Wealth, Income

A legacy of racism and economic privilege, currently enshrined in many components of both federal and state tax codes, has helped to produce and uphold searing wealth inequities. The extreme and racialized concentration of white wealth in the US and DC has its roots not only in the enslavement of African people but through centuries of racialized policymaking, including, Jim Crow segregation, Black codes, tax limits and preferences, and many other policies designed to systematically deny Black people and non-Black people of color access to economic opportunity and to privilege white wealth.[11],[12]

One result is that wealth and extreme wealth are highly concentrated among white households. In the DC area, the typical white household has 81 times the wealth of a typical Black household.[13] Median white household wealth was estimated at $284,000, compared with just $3,500 for Black households, in 2013-2014, the most recent data from an Urban Institute report show. Nationally, the white-Black median wealth gap was estimated to be large but lower at a 10-fold difference in 2016.[14] Extreme wealth is more skewed and excessively concentrated among white households. Just 0.4 percent of DC tax units (roughly 1,500 households based on the number of tax filers in 2019) have net worth over $30 million.[15] Yet, these same tax units hold nearly half (46 percent) of all wealth in the District.[16] In fact, DC’s concentration of extreme wealth is even more severe than it is nationwide. DC is home to only 0.2 percent of the nation’s total population but houses 0.5 percent of the nation’s extreme wealth.[17]

Wealth inequality matters because wealth offers people choices and opportunity, helps people endure hard times such as losing a job, and can be passed on to future generations. It also undermines democracy through the consolidation of power and influence, which can be used to further concentrate wealth. Wealth inequality, in contrast, harms us all by exacerbating racial inequality and limiting economic opportunity.[18] Tax policy offers a powerful means towards addressing DC’s stark and persistent level of wealth inequality, but DC’s current tax code falls short of its potential, particularly as it relates to capital gains, which are generated by wealth.

Under current law, capital gains—the increase in value of assets such as stocks, real estate, or other investments—are taxable only if the asset generating those gains is sold. Unlike wages or salaries, which are taxed when earned, and often withheld from employee paychecks, both the federal and DC governments tax income from capital gains upon an asset’s sale (i.e., when the gain is “realized”). Capital gains income is reported as the difference between the purchase price (“basis”) and final sale price of an asset. Whereas taxpayers who earn their living from work pay taxes on that income annually, wealthy individuals can amass wealth and increase their after-tax income by deferring taxes on accrued gains into the future, and in some cases, past death.

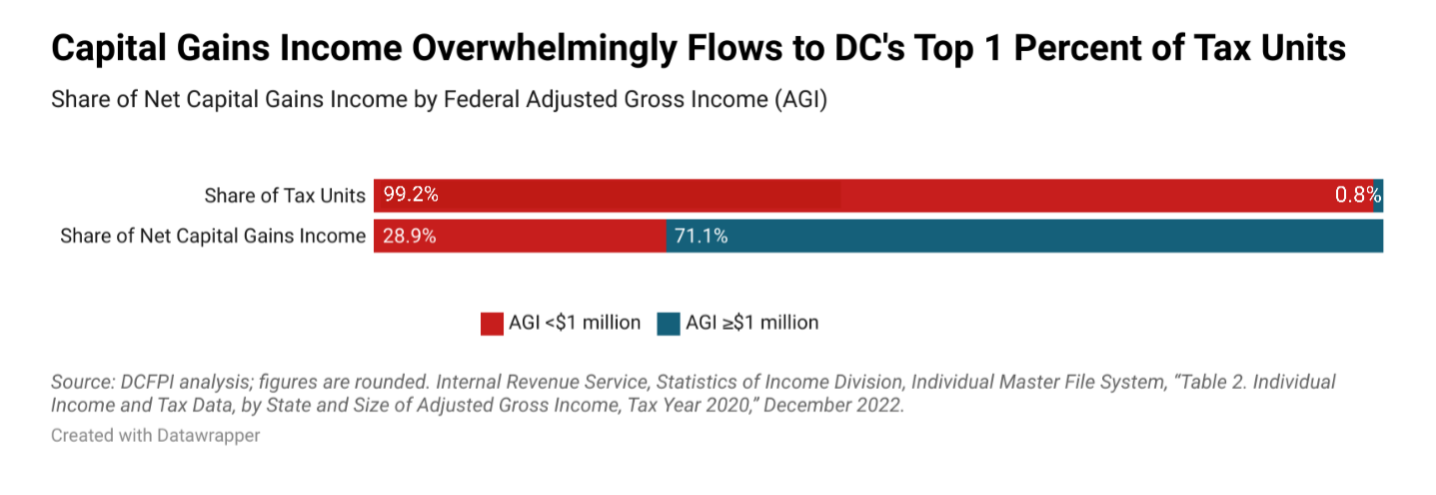

Like wealth, capital gains income disproportionately accrues to high-income, white households. In 2020, for example, less than 1 percent of DC filers reported $1 million or more in federal adjusted gross income (AGI), but those filers claimed 71 percent of net capital gains income in the District (Figure 1). This is an even greater share than in the US as a whole, where filers making over $1 million a year claimed 65 percent of the nation’s net capital gains income.[19] By design, tax advantages for capital gains accrue to a narrow share of wealthy, high-income households, exacerbating income, wealth, and racial inequality.

The US Tax Code Favors Capital Gains, At Great Cost

Favorable treatment of capital gains starts at the federal level, where the Treasury Department estimates that capital gains-related tax provisions will be worth an estimated $1.5 trillion in forgone federal tax revenue over the next ten years.[20] There are three tax advantages in particular that incentivize wealthy people to devise elaborate tax shelters to turn as much of their income into capital gains as possible, and hold onto assets far longer than might otherwise be economically efficient, even if they have better investment opportunities.[21] Those advantages include lower tax rates, the delay of tax payments, and the ability to wipe out capital gains tax liability altogether.

Lower rates for long-term capital gains income. The federal government taxes income from long-term capital gains—assets held for more than one year—at a lower rate than ordinary income from wages or salaries, costing roughly $112 billion in forgone revenue in fiscal year (FY) 2022, diverting critical revenue away from other public priorities and enhancing the income and wealth of the top 1 percent.[22] People earning their income from work pay a top federal marginal rate of 37 percent, while income from long-term capital gains is taxed at a top marginal rate of only 23.8 percent.[23] This preferential rate diminishes the progressivity of the federal income tax code because the majority of capital gains income is claimed by the highest-income taxpayers, as shown in Figure 1. Those high-income filers pay a smaller share of their income in taxes than they would if their income from wealth were taxed at the same rate as income from work.

Looking at preferential rates for long-term capital gains (as well as qualified dividends, which are payments made by a company to its shareholders from its profits), one analysis found that 75 percent of the benefits from these lower tax rates nationally goes to the top 1 percent of households with the highest incomes.[24] The average benefit to these households was worth roughly 6 percent of their after-tax income.[25] Experts argue that lower tax rates on capital gains are a key features of many tax shelters that “employ sophisticated financial techniques to covert ordinary income…to capital gains,” leading to less economic efficiency and growth.[26]

Deferral—the ability to delay paying taxes on capital gains. Wealthy filers are not required to pay tax on any increase in value of an asset until that gain is “realized” by selling the asset. For example, if a person buys $10,000 worth of a company’s stock, holds the shares for several years, and finally sells them for a total value of $20,000, the federal government taxes the $10,000 increase in value only in the year the stock sells rather than each year that the stock gains value. This contrasts with wage or salary-based income, which taxpayers must pay taxes on in the year that they earn it. The same is true for interest on savings accounts, which are taxed annually.

A large share of US wealth exists in the form of “unrealized” gains—that is, an increase in the value of assets that have yet to be sold. Among ultra-rich US families, 43 percent of their net worth is held in unrealized gains.[27] Like overall wealth, the distribution of unrealized gains is also racialized. One analysis found that 89 percent of unrealized capital gains over $2 million belonged to white families, compared to 1 percent for Black and Hispanic families.[28]

The ability to defer also gives wealthy taxpayers the opportunity to sell an asset when it makes the most strategic sense for them, such as in a year in which they will have other large capital losses to offset the gain. And in a strategy termed, “Buy, Borrow, Die,” some wealthy taxpayers use unrealized gains as collateral to obtain large, tax-free lines of credit without generating “taxable” income.[29],[30] In such cases, wealthy taxpayers can use their untaxed income to access significant amounts of untaxed cash to “live very extraordinarily well” while continuing to grow their wealth, untaxed, indefinitely.[31]

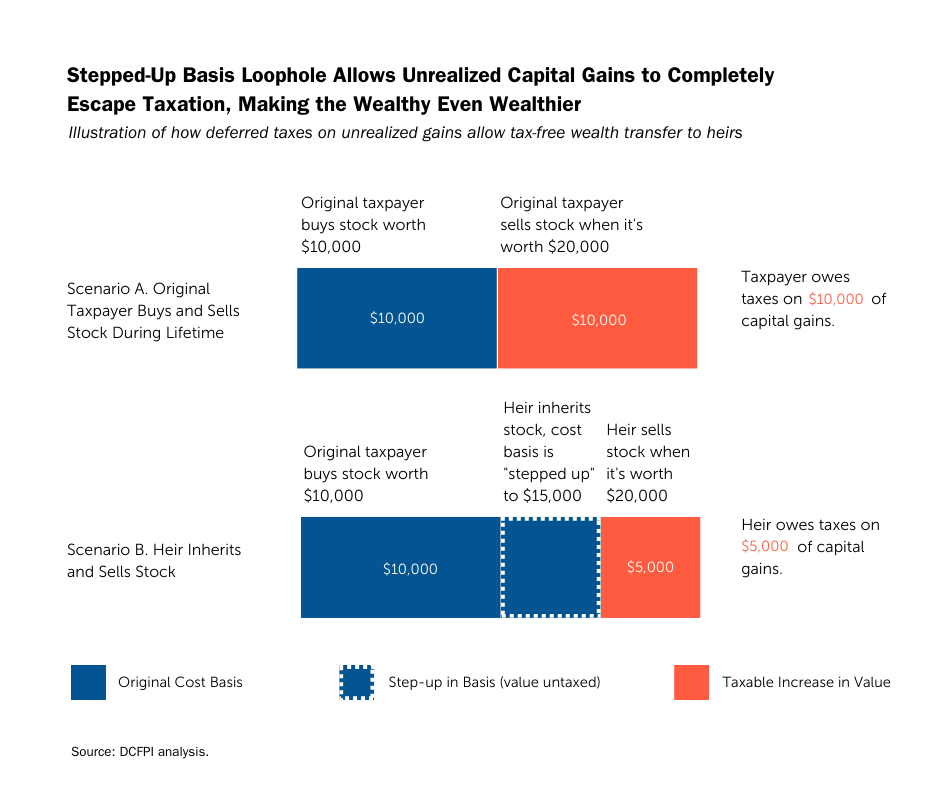

Stepped-up basis—the ability to wipe out capital gains tax liability at death. If an investor leaves an appreciated asset to an heir upon death, neither they nor the heir will ever owe capital gains tax on the growth in value up to that point. The tax code “steps up” the value of the asset from the original price (or “basis”) to the fair market value at the time of death, effectively wiping out tax liability for the entire capital gain. This allows the wealthy to pass decades or a lifetime of untaxed investment income to their heirs when they die, costing $43.9 billion in forgone revenue in FY 2022.[32] This tax benefit is called the “stepped-up basis,” or sometimes the “Angel of Death” loophole, aptly describing the large tax windfall that wealthy heirs receive from the provision.[33]

Following the previous example above, if a person bought $10,000 worth of stock and held onto it until they died, when the shares were then worth $15,000, the tax code steps up the basis to $15,000 for the heir inheriting those shares. The heir would not owe any taxes on the $5,000 increase in value between the original acquisition and the original taxpayer’s death. If the heir then sold the shares later for a total value of $20,000, they would only owe tax on the $5,000 increase in value during the time when they personally held the stock, rather than the full $10,000 increase in value since the stock’s original acquisition (Figure 2, pg. 7). Stepped-up basis also occurs with other appreciated assets, such as real estate or closely held businesses, that are passed from one generation to the next.

Stepped-up basis notably, also makes possible the third step in the “Buy, Borrow, Die” strategy, wherein deferred taxes on unrealized gains are passed onto heirs tax-free.[34] This loophole encourages wealthy people to turn as much of their income as possible into assets that will generate capital gains and hold on to their assets until death, and it is one of the key ways extreme wealth—primarily held by white people—is concentrated over generations in America. Nationally, 99 percent of the revenue from eliminating stepped-up basis would come from the top 1 percent of filers, and 80 percent would come from the top 0.1 percent, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ (CBPP) analysis of 2015 Treasury Department data.[35] And, of the $4.25 trillion of wealth currently held by US billionaires, $2.7 trillion consists of untaxed capital gains, according to economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman.[36]

At death, if those gains remain unrealized, they will completely escape income taxation under current stepped-up-basis rules. (In theory, the gains may be subject to estate taxes, although the wealthy have many strategies available to avoid them as well, such as the sophisticated use of trusts.)

Disparities in inheritance and intergenerational transfers are primary contributors to the racial wealth gap.[37] One study found that 19 percent of white families expect an inheritance, compared to just 6 percent of Black families and 4 percent of Hispanic families.[38] And, among families who do receive an inheritance, white families receive an average inheritance nearly three times larger than that received by Black or Hispanic families.[39] Tax preferences like stepped-up basis at death allow wealthy taxpayers to transfer large amounts of intergenerational wealth to their heirs without taxation, exacerbating existing racial disparities in wealth.

Other Special Rules for Capital Gains in the Federal Tax Code

The federal government provides additional exemptions and exclusions that reduce the amount of capital gains income subject to tax.

Treatment of capital losses. If a taxpayer’s capital losses exceed their gains in a given tax year, the federal government and most states allow them to deduct up to $3,000 in net capital losses from their ordinary income (or up to $1,500 for taxpayers married and filing separately). Taxpayers may also carry any unused capital losses forward to offset income in subsequent years. This ability to use annual capital losses to offset income from earnings is even available to taxpayers who ultimately will receive enormous tax savings from stepped-up basis.

Personal Residence Exclusion. Federal law allows homeowners to exclude up to $250,000 (for single taxpayers) or $500,000 (for married taxpayers filing jointly) of capital gains from the sale or exchange of their principal residence. This is a sizable exclusion, worth roughly $49 billion in FY 2022.

Opportunity Zones. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act allowed investors to defer, reduce, or eliminate tax owed on gains from investments in a “Qualified Opportunity Fund.” The federal capital gains benefits are generous, especially if the investment is held for at least ten years, at which point capital gains from the project are permanently excluded from taxation. This expenditure was worth roughly $3.1 billion of forgone revenue in FY 2022.

Other miscellaneous exclusions. The federal government also offers a variety of additional exclusions, such as for like-kind asset exchanges, assets transferred as a gift, gains from sales of small business stock, non-dealer installment sales, and distribution from redemption of stock to pay taxes imposed at death, for example.

Sources: For a summary of federal capital gains policy, see Gravelle, “Capital Gains Taxes: An Overview of the Issues,” 2022. For tax expenditure estimates, see US Department of Treasury, “Table 2b. Estimates of Total Individual Income Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2022-2032,” March 2023.

How DC Treats Capital Gains

Capital gains income is an important component of gross income in DC. In 2020, income from realized capital gains made up 11 percent of DC’s total AGI, compared to only 9 percent for the US as a whole, and 7 percent and 6 percent in neighboring states Virginia and Maryland, respectively.[40] This is true, at least in part, because DC has a greater share of tax filers in high-income brackets than the nation as a whole. In 2020, 10 percent of DC filers reported AGI between $200,000 and $1 million (compared to just 5 percent of filers nationally), and 0.76 percent of filers reported AGI of $1 million or more (compared to 0.37 percent nationally).[41]

Moreover, although DC derives most of its individual income tax revenue from ordinary sources of income, like wages and salaries, capital gains income is still an important component of DC’s income tax revenue. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) estimates that approximately 14 percent of DC personal income tax revenue comes from capital gains taxes.[42] This is larger than the 11 percent of total AGI in the federal data, because capital gains income is disproportionately received by high-income taxpayers, who are taxed at higher rates under DC’s progressive income tax.

Although some of DC’s policies help to offset the considerable advantages that the federal tax code gives to capital gains, DC (like most states) largely conforms to federal policies and to the federal definition of AGI, which favors income from wealth over ordinary income from wages and salaries.

DC taxes ordinary and capital gains income at the same rate. Like most states, DC taxes income from capital gains at the same rate as ordinary income. This is one of the few ways that most states and DC have decoupled from the federal treatment of capital gains.[43] DC taxes both short- and long-term capital gains income under the same marginal tax rate structure that applies to ordinary income, with a top marginal rate of 10.75 percent.[44] Taxing income from work and wealth according to the same progressive rate structure helps even the playing field and reduce economic distortions at the local level, but it doesn’t fully compensate for the preferential treatment that comes from conforming to most major components of the federal tax code.

DC still conforms to costly federal policies. Most states and DC “piggyback” off the federal government by using federal AGI as the basis for their income tax calculations.[45] Because of this, most states and DC remain coupled to federal tax policies that, for example, allow taxpayers to avoid paying tax on capital gains derived from the sale of a personal residence (see box 2), or give heirs the benefit of a stepped-up basis on inherited assets, among other benefits.[46]

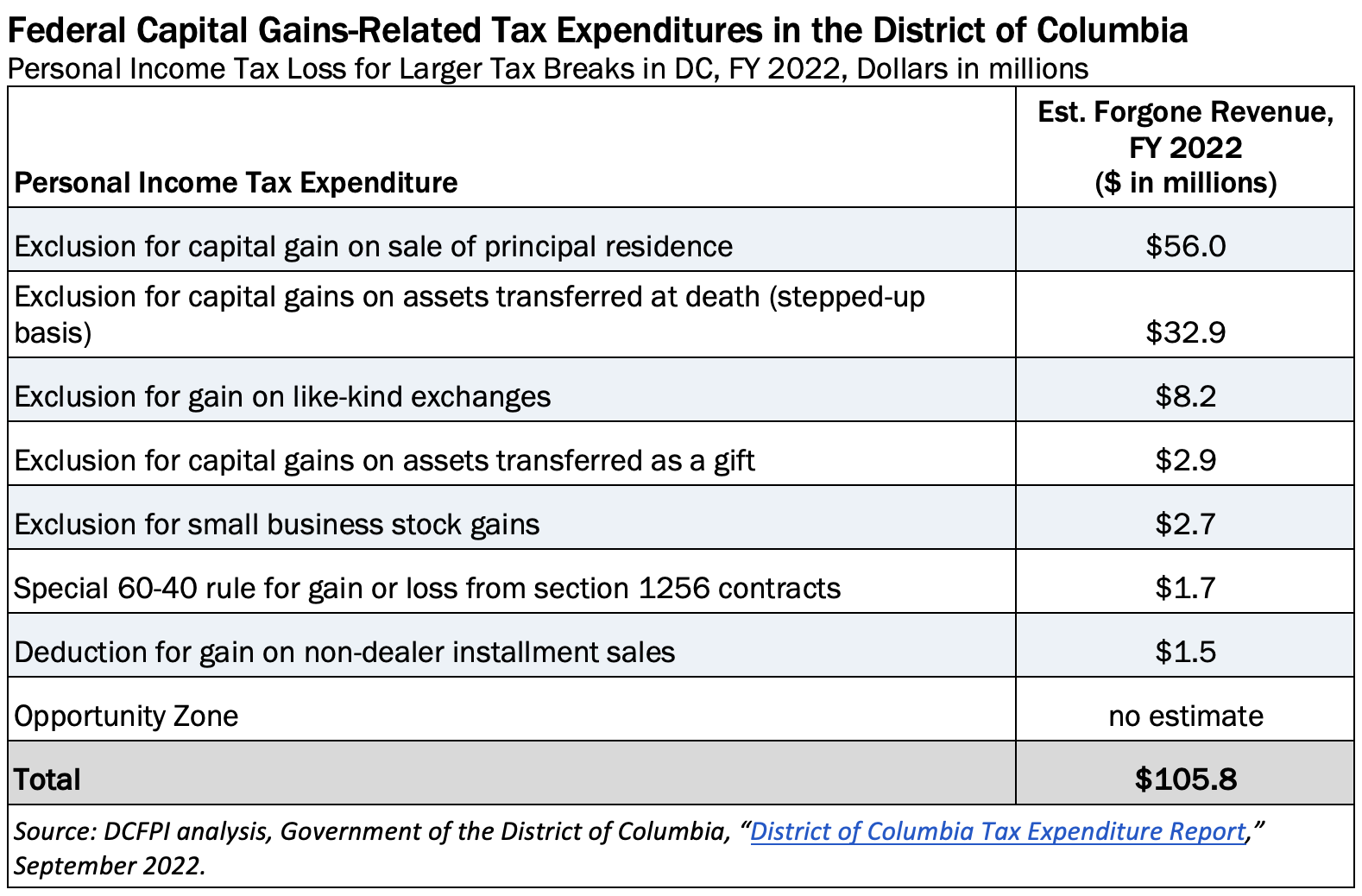

Like the federal government, DC allows taxpayers to defer taxes on unrealized capital gains and allows taxpayers to use capital losses to offset ordinary income such as wages and salaries (see Other Special Rules for Capital Gains in the Federal Tax Code for more on treatment of capital losses).[47] In fact, DC conforms to almost all capital gains-related exclusions and deductions in the federal tax code. Conformity to these federal provisions make up some of the District’s largest capital gains-related tax expenditures and together cost DC over $100 million in personal income tax collections in FY 2022 (Table 1, pg. 10).

The largest of these expenditures is the exclusion of capital gains income from the sale of a principal residence (see more in “see Other Special Rules for Capital Gains in the Federal Tax Code), which cost the District a loss of $56 million in personal income tax revenue in FY 2022. The second largest expenditure is the stepped-up basis at death, costing DC roughly $33 million in FY 2022. DC is not alone in following along with these provisions, despite the loss in personal income tax revenue. No states currently decouple from either of these provisions in federal law.

When it comes to Opportunity Zones, which allow investors to defer, reduce, or eliminate tax owed on gains from investments in a “Qualified Opportunity Fund,” DC has elected to impose stricter requirements on which investments qualify for this benefit.[48] DC investors can still benefit from these generous capital gains exclusions, but eligibility is narrower.[49] There is no estimate available on how much forgone revenue this provision costs DC.

DC has temporarily suspended its one local capital gains exclusion: tax benefits for investments in Qualified High Technology Companies (QHTCs). The District does not currently offer other exclusions that reduce taxable capital gains income for individuals beyond those that conform to the federal tax code. DC’s only local exclusion in recent years has been the reduced capital gains tax rate of 3 percent available to investors in QHTCs. Lawmakers suspended this local exclusion in 2020, but it is slated to resume in 2025.[50]

Strengthening DC’ Capital Gains Taxes Can Help Close the Racial Wealth Gap and Raise Revenue

In sum, although the individual income tax is one of DC’s main taxes, it’s substantially a voluntary tax for the richest residents with unrealized gains who can take easily available steps to avoid paying it. DC can help even the playing field between wealth and work by reforming capital gains policies that currently exacerbate income, wealth, and racial inequality.

Permanently suspend and adopt no new local capital gains exclusions.

The District should permanently suspend any extraneous local exclusions or deductions, like the QHTC, that reduce the amount of capital gains income subject to taxation. Such exclusions, while popular at the state level, often reduce the base of taxable income without offering additional economic benefits. In 2014, for example, the DC Tax Revision Commission recommended against providing a preferential rate to investments in QHTCs, suggesting it was not the best means to diversify the District’s economy and that “targeting capital gains benefits is inherently difficult.”[51] While this feature of the QHTC program is currently suspended, it is slated to make a return in FY 2025.[52] The District should make this suspension permanent and avoid adopting any similar exclusions that reduce revenue for the District.

Raise the tax rate on capital gains income.

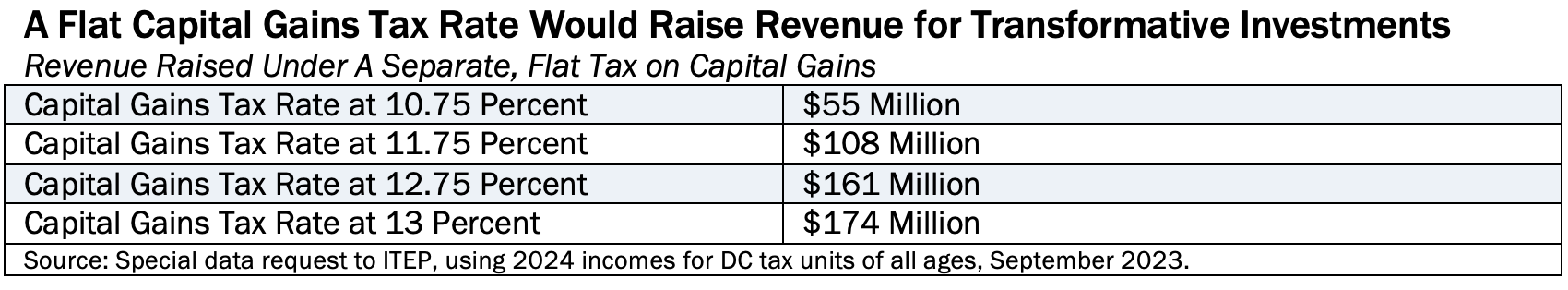

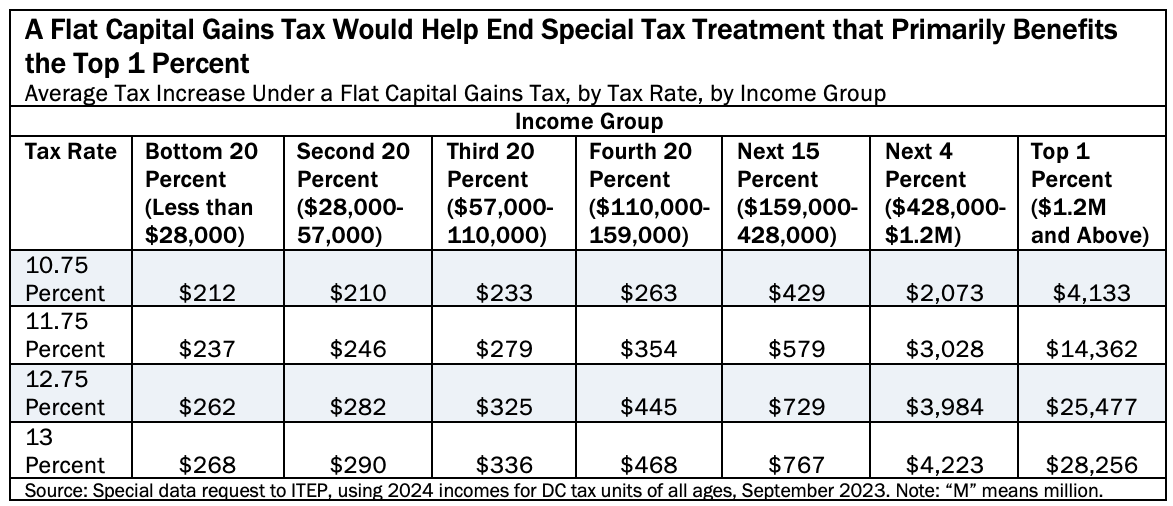

To boost equity in the tax code, DC could raise tax rates on capital gains income.[53] DC has many options for implementing a higher rate. For example, DC could tax capital gains separately from ordinary income and at a higher flat rate. At DCFPI’s request, ITEP modeled the impact of four flat capital gains tax rates: the current top marginal income tax rate of 10.75 percent, 11.75 percent, 12.75 percent, and 13 percent. Under this design, all DC taxpayers with capital gains income would face a tax increase. (This analysis does not include retirement income in the definition of capital gains income.[54])

Raising the rate on capital gains taxes under these parameters would raise between $55 million and $174 million, according to ITEP’s modeling for 2024 (Table 2). Two of these proposals raise enough revenue to fully cover the $115.2 million cost of a $1,500 DC Child Tax Credit.[55]

Regardless of the tax rate, the increase would affect about 14 percent of DC taxpayers, with filers in the top 20 percent of the income distribution (with incomes above $159,000) absorbing most of the tax increase. Implementing a separate, flat tax rate of 10.75 percent on capital gains would raise taxes on groups across the income distribution but keep the tax rate at the same level for the filers in the top 1 percent who are already subject to this top marginal tax rate. This weakens the impact on equity compared to the other three tax rates that ITEP modeled. Even so, six in ten filers in the top 1 percent—those with incomes above $1.2 million—would face a tax increase. Implementing a separate, flat capital gains tax rate between 11.75 percent and 13 percent would result in eight in ten of those in the top 1 percent paying.

For those in the top 20 percent of tax units but not the top 5 percent (those with incomes between $159,000 and $428,000), the average tax increase under the four parameters would range from $429 to $767 (Table 3). For the next 4 percent of tax units (with incomes between $428,000 and $1.2 million), the average tax increase under the four parameters would range from $2,073 to $4,223. The average tax increase would be highest for those in the top 1 percent (with incomes $1.2 million and above) under the four parameters, averaging between $4,133 and $28,256. Black and Hispanic families make up 49.3 percent of all tax returns in DC, but a mere 5.7 percent of tax returns in the top 20 percent of filers. It is also likely that under each proposal, tax units comprised of people of color would see a smaller average tax increase under the four capital gains rate increases.

Looking across the bottom 80 percent of the income distribution (with incomes below $159,000), taxpayers would see an average tax increase between $212 and $468 under the four parameters. However, the primary goal of improving the way DC taxes capital gains is to deconcentrate extreme wealth and narrow racial equity within DC’s tax code, not to raise taxes on families with low- and moderate-incomes and undermine racial justice. If DC were to adopt a flat, separate capital gains income tax, it could pair that policy with an offset for any tax increases incurred by the bottom 80 percent of taxpayers. One idea might be to adopt a capital gains tax credit that automatically refunds taxpayers up to a certain income level the difference between capital gains taxes paid under the flat rate and what taxes would be owed under the marginal tax rates for ordinary income when they file a return. The credit might gradually decrease as income rises for filers in the fourth quintile to remove any cliff effects that might incentivize tax avoidance.

Alternatively, DC could also raise the tax rate for all capital gains income above a certain threshold. For example, Minnesota’s governor recently signed a bill that imposes a new tax on net investment income of 1 percent on individuals, estates, and trusts with more than $1 million in net investment income.[56] Net investment income is defined by the federal government and includes but is not limited to interest, dividends, and capital gains.[57] The tax is expected to raise an additional $86 million in general fund revenue in FY 2025.[58]

One caveat is that while a policy design based on an income test avoids raising taxes on low- and middle-income households, it may incentivize filers to avoid the income threshold that triggers the higher capital gains rate or a tax on investment income if a filer’s income is very close to the selected threshold.

Repeal the “stepped-up basis” for capital gains bequeathed at death.

As previously discussed, this provision of the tax code enables wealthy people who have avoided capital gains taxes on the growth of assets during their lifetimes to pass them to their heirs tax-free at death. National experts on taxes with an eye towards racial justice have recommended that states decouple from the federal government on this provision, which exacerbates wealth and racial inequality.[59]

Decoupling from this provision would complement any concurrent plan to raise capital gains income tax rates in the District. Federally, eliminating this provision has been recommended as an accompaniment to any increase in the capital gains tax rate.[60] If tax rates are raised without eliminating this provision, then the wealthiest taxpayers who are able might be tempted to hold onto their assets for longer periods—longer, even, than is economically productive—simply to avoid the higher tax. This is known as the “lock-in effect.” Removing the stepped-up basis, however, guarantees that those gains will eventually be taxed, thus discouraging taxpayers from deferring their gains for unreasonably long periods.

There are two options for eliminating the stepped-up basis. The first would be to replace it with the carryover basis, which is what the federal government currently uses for gifts that are bequeathed from one person to another during the giver’s lifetime.[61] With a carryover basis, the recipient can still defer tax on any assets that are transferred to them at death by waiting to sell those assets. However, when they do sell the assets, they will be taxed on the full value of the gain, just as if the original owner had sold it during their lifetime. The cost basis is therefore “carried over” from the original taxpayer, rather than “stepped up” to eliminate the gain.

The second option is to simply tax gains at death, allowing for a payment schedule if the taxpayer faces liquidity problems.[62] Taxing gains this way treats death as a “realizing event,” similar to the sale of an asset. Under this option, the heir would not be able to defer taxes on the assets into an uncertain future but would be required to pay taxes on any gains accrued up until that point. Adopting either of these options, preferably along with a higher rate on capital gains income, would eliminate some of the largest capital gains advantages and disrupt wealthy taxpayers’ ability to amass large fortunes that they can pass on to heirs tax-free.

Whereas eliminating capital gains exclusions and raising rates could be implemented at the DC level relatively quickly, in the absence of similar policy changes at the federal level, eliminating the stepped-up basis would require considerable discussion with tax professionals within and outside of DC government due to the technical challenges involved in designing and implementing this policy. For example, one challenge of taxing appreciated assets is that it may be difficult for heirs to determine the original price (or basis) of the asset(s) being passed on, especially for assets acquired many decades earlier. DC would need the resources and ability to collect information to accurately estimate and audit an asset’s value change over time; these calculations are more difficult for complex and unique assets such as intellectual property rights or stakes in private businesses.

To give the Office of the Chief Financial Officer (OCFO) staff and tax professionals time to address some of the technical barriers, DC lawmakers could approve eliminating the stepped-up basis with an effective date in the future that specifically requires and provides funding for staff or other experts to address these barriers prior to the effective date.

Require the OCFO to develop a method for taxing gains as they accrue.

For example, DC could develop a “mark-to-market” system, which would tax increases in value annually, rather than waiting until those assets are sold. Taxing only a share of unrealized gains is one way to phase in a mark-to-market system, helping to offset challenges related to taxpayer liquidity that might come from trying to tax the entire stock of unrealized gains at once. Additionally, mark-to-market rules could be applied to all of a taxpayer’s historical unrealized gains or imposed only on a prospective basis. Another option would be to explore adopting such a system for only the highest-income filers, which could help mitigate administrative complexity. Just 0.4 percent of tax units in DC hold $71 billion in unrealized capital gains, and taxing even just 50 percent of those unrealized gains at a one percent rate would have yielded $355 million in revenue for DC in 2022.[63]

Implementing a comprehensive mark-to-market income tax, however, would also be very technically complex, given that it requires annual valuations of all assets to measure the annual gains and estimate taxes owed. For certain types of assets, like a work of art, annual valuations could impose administrative burdens on taxpayers and lead to tax avoidance, as taxpayers shop around for the lowest appraisal. Some tax experts believe that a mark-to-market system would most realistically be implemented only if piggy-backed on a change in federal policy or in a state with significant internal expertise and resources. However, other tax law scholars have published ideas on how states could meet this administrative challenge.[64] CBPP has also argued that governments could treat non-publicly-traded assets differently:

“…instead of imposing an annual capital gains tax on unrealized gains in those assets, DC could continue to defer taxes on them until realization, but impose a one-time “deferral charge” when the asset is eventually sold, comprising the amount of capital gains tax plus an amount similar to interest that would be based on how long the asset was held before it was sold.”[65]

The OCFO could look at the advice of such experts and devise a plan for the District to do this in a future year.

Together, these proposals for strengthening taxation of capital gains could raise resources to invest in shared abundance, ensure a greater share of wealthy residents pay a fairer amount of taxes, and help correct the racist harm in the tax system.

[1] Special data request to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) in 2021, updating data from the sixth edition of Who Pays: A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States.

[2] Kilolo Kijakazi et al, “The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital,” A Joint Publication of the Urban Institute, Duke University, The New School, and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development, November 2016.

[3] Carl Davis, Emma Sifre, and Spandan Marasini, “The Geographic Distribution of Extreme Wealth in the U.S.: Estimating Wealth Levels and Potential Wealth Tax Bases Across States,” Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), October 2022. And, data provided by ITEP to DCFPI in October 2022. Data reflects ITEP’s Microsimulation Tax Model analysis, using data from the Internal Revenue Services, Survey of Consumer Finances, Forbes, and other sources. Ultra wealthy includes those with wealth of at least $30 million.

[4] Cristobal Young, The Myth of Millionaire Tax Flight: How Place Still Mattes for the Rich,” Stanford University Press, 2017.

[5] DCFPI’s calculation based on Young’s methods and data in a presentation on his book’s findings. See slides 28-32 and slide 40 here.

[6] Ibid, see slide 47.

[7] Cristobal Young and Ithai Lurie, “Taxing the Rich: How Incentives and Embeddedness Shape Millionaire Tax Flight,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, Working Paper Series, July 2022.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Cristobal Young, “Millionaire Migration and Taxation of Top Incomes: Evidence from Big Administrative Data,” A Presentation for the DC Tax Revision Commission, accessed October 25, 2023. See slide 44.

[10] See, for example, Karen Smith Conway and Jonathan Rork, “State Death Taxes and Elderly Migration: The Chicken or the Egg,” National Tax Journal, March 2006; Conway and Rork, “No Country for Old Men (Or Women): Do State Tax Policies Drive Away the Elderly?” National Tax Journal, June 2012; and, Jon Bakija and Joel Slemrod, “Do the Rich Flee from High State Taxes? Evidence from Federal Estate Tax Returns,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 10645, July 2004.

[11] See Michael Leachman, et al., “Advancing Racial Equity With State Tax Policy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), November 15, 2018.

[12] Liz Mineo, “Racial Wealth Gap May Be a Key to Other Inequities,” Harvard Gazette, June 3, 2021; and Christina Pazzanese, “Piketty’s New Book Explores How Economic Inequality Is Perpetuated,” Harvard Gazette, March 3, 2020.

[13] Kilolo Kijakazi et al. 2016.

[14] Vanessa Williamson, “Closing the Racial Wealth Gap Requires Heavy, Progressive Taxation of Wealth,” Brookings Institution December 9, 2020.

[15] Davis, Sifre, and Marasini 2022.

[16] Data provided to the DC Fiscal Policy Institute by Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy in October 2022. Also, see: Erica Williams, “DC’s Extreme Wealth Concentration Exacerbates Racial Inequality, Limits Economic Opportunity,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, October 2022.

[17] Davis, Sifre, and Marasini 2022.

[18] Mineo 2021.

[19] Filers claiming AGI of over $1 million made up 0.37 percent of US filers and 0.76 percent of DC filers. DCFPI analysis of IRS, Statistics of Income Division, Individual Master File System, “Table 2. Individual Income and Tax Data, by State and Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2020,” December 2022.

[20] US Department of the Treasury, “Frequently Asked Questions: Tax Expenditures,” June 2023.

[21] Congressional Research Service, “Tax Expenditures: Compendium of Background Material on Individual Provisions,” S. Rep. No. 45, 112th Cong., 2d Sess., page 430.

[22] See income tax provision number 70 in “Table 2b. Estimates of Total Individual Income Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2022-2032,” in U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury), Tax Expenditures, March 2023.

[23] The top marginal rate for earned income may be higher (40.8 percent) for some taxpayers with net investment income outside of capital gains, like interest, dividends, annuities, royalties, certain rents, and certain other passive business income not subject to the corporate tax. For a summary of federal capital gains policy, see Jane G. Gravelle, “Capital Gains Taxes: An Overview of the Issues,” Congressional Research Service, May 24, 2022.

[24] Frank Sammartino and Eric Toder, “What Are the Largest Nonbusiness Tax Expenditures?,” Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, July 17, 2019.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Tax Policy Center, “What is the effect of a lower tax rate for capital gains? Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System,” Updated May 2020.

[27] Davis, Sifre, and Marasini 2022.

[28] Joe Hughes and Emma Sifre, “Investment Income and Racial Inequality,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, October 14, 2021.

[29] Edward J. McCaffery, “The Death of the Income Tax (or, The Rise of America’s Universal Wage Tax),” Indiana Law Journal 95, no. 4 (2020).

[30] ProPublica has documented several instances of the very wealthy accessing large lines of credit, secured by a portfolio of unrealized gains. See Jesse Eisinger, Jeff Ernsthausen, and Paul Kiel, “The Secret IRS Files: Trove of Never-Before-Seen Records Reveal How the Wealthiest Avoid Income Tax,” ProPublica, June 8, 2021.

[31] Edward J. McCaffery, “The Death of the Income Tax (or, the Rise of America’s Universal Wage Tax),” Indiana Law Journal, April 10, 2019, pages 24- 25. And, John Hyatt,” How America’s Richest People Can Access Billions Without Selling Their Stock,” Forbes Magazine, November 11, 2021, documents how Robert Stiller, founder of Green Mountain Coffee Roaster, borrowed against his company shares to live an “extravagant lifestyle” in lieu of selling his shares.

[32] US Department of the Treasury, “Table 2b. Estimates of Total Individual Income Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2022-2032,” March 2023. See income tax provision number 70.

[33] Coined by Michael Kinseley in “The ‘Angel of Death’ Loophole,” Washington Post, June 25, 1987; for more discussion see, Leonard E. Burman, “President Obama Targets the ‘Angel of Death’ Capital Gains Tax Loophole,” TaxVox, January 18, 2015.

[34] McCaffery 2020.

[35] Elizabeth McNichol, “State Taxes on Capital Gains,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 11, 2018.

[36] Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, “How to Get $1 Trillion from 1000 Billionaires: Tax their Gains Now,” University of California Berkeley, April 14, 2021.

[37] Darrick Hamilton and William A. Darity, Jr., “The Political Economy of Education, Financial Literacy, and the Racial Wealth Gap,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 99, no. 1 (2017): 59–76.

[38] Jeffrey P. Thompson and Gustavo A. Suarez, “Exploring the Racial Wealth Gap Using the Survey of Consumer Finances,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September 2015.

[39] Thompson and Suarez 2015.

[40] DCFPI analysis of IRS, Statistics of Income Division, Individual Master File System, “Table 2. Individual Income and Tax Data, by State and Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2020,” December 2022.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Special data request to ITEP, August 2023. To model this estimate, ITEP compared a version of DC law with capital gains income removed from current law, and used the results to determine the share of income tax revenue that comes from capital gains income.

[43] For a summary of state-by-state capital gains tax policy, see “State Treatment of Capital Gains and Losses: Tax Year 2021,” Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

[44] For state-by-state income tax rates, see “State Individual Income Tax Rates,” Federation of Tax Administrators (FTA), January 1, 2023; see also §47–1806.03 of the Code of the District of Columbia, as referenced in “DC Individual and Fiduciary Income Tax Rates,” Government of the District of Columbia.

[45] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “State Personal Income Tax Bases in 2020,” accessed June 29, 2023. For more discussion of federal conformity tax expenditures in DC, see Government of the District of Columbia, “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022.

[46] For a more comprehensive discussion of all federal exclusions and deductions, see Jane G. Gravelle, “Capital Gains Taxes: An Overview of the Issues,” Congressional Research Service, May 24, 2022.

[47] For a summary of state-by-state capital gains tax policy, see “State Treatment of Capital Gains and Losses: Tax Year 2021,” Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC).

[48] DC elected to decouple from provisions of the federal law in 2020 with the “Fiscal Year 2021 Budget Support Emergency Amendment Act of 2020.” See “District of Columbia Tax Rate Changes Effective October 1, 2020,” DC Office of Tax and Revenue, September 1, 2020.

[49] For additional discussion see Government of the District of Columbia, “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022.

[50] See “District of Columbia Tax Rate Changes Effective October 1, 2020,” DC Office of Tax and Revenue, September 1, 2020.

[51] DC Tax Revision Commission, “Final Report,” May 2014.

[52] DC § 47–1817.07a, “Tax on Capital Gain from the Sale of Exchange of a Qualified High Technology Company Investment.”

[53] See Elizabeth McNichol, “State Taxes on Capital Gains,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 11, 2018; and Marco Guzman, “State Taxation of Capital Gains: The Folly of Tax Cuts & Case for Proactive Reforms,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, September 25, 2020.

[54] For this analysis, ITEP did not include retirement income as a part of the capital gains definition. In ITEP’s model, capital gains are taxable brokerage accounts and other non-retirement sources of gains, like selling real estate, art or antiques, or a business. For this analysis, ITEP excluded earnings that show up in retirement accounts, such as pensions.

[55] DCFPI estimates that a $1,500 Child Tax Credit under certain parameters would cost approximately $115.2 million. See, Erica Williams, “A Child Tax Credit Would Reduce Child Poverty, Strengthen Basic Income, and Advance Racial Justice in DC,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, March 6, 2023. In FY 2023, DC allocated $60 million in local dollars to support the child care subsidy program.

[56] Minnesota Department of Revenue, “Tax Law Changes,” 2023.

[57] Internal Revenue Service, “Questions and Answers on the Net Investment Income Tax,” September 29, 2022.

[58] Minnesota Department of Revenue. “Analysis of Session Laws 2023, Chapter 64 (H.F. 1938),” St. Paul, MN, June 5, 2023.

[59] McNichol 2018 and Guzman 2020.

[60] For example, see discussion in Burman 2015.

[61] See Tax Policy Center, “What Is the Difference between Carryover Basis and a Stepped-up basis?,” May 2020.

[62] For discussion see Stephen M. Rosenthal and Robert McClelland, “Taxing Capital Gains at Death at A Higher Rate Than During Life,” TaxVox (blog), May 13, 2022.

[63] Davis, Sifre, and Marasini 2022

[64] Brian Galle, David Gamage, and Darien Shanske, “Solving the Valuation Challenge: The ULTRA Method for Taxing Extreme Wealth,” Duke Law Journal.

[65] Chuck Marr, Samantha Jacoby, and Kathleen Bryant, “Substantial Income of Wealthy Households Escapes Annual Taxation Or Enjoys Special Tax Breaks Reform Is Needed,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 2019, page 19.