Chairman Mendelson and members of the Committee of the Whole, thank you for the opportunity to submit written testimony. My name is Erica Williams, and I am the executive director of the DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI) where we shape racially-just tax, budget, and policy decisions by centering Black and brown communities in our research and analysis, community partnerships, and advocacy efforts to advance an antiracist, equitable future. My organization is a proud member of the Fair Budget Coalition, and we join with them in the conviction that safety is stable, healthy communities, and something that we all want.

Despite calling for “shared sacrifice” in a time of budget constraints, Mayor Bowser’s proposed fiscal year (FY) 2025 budget and financial plan demands the biggest sacrifices from DC’s lowest income residents—who, because of historic and structural racism, are disproportionately Black and brown residents. The mayor’s budget backtracks on previous commitments to low-paid residents by taking an ax to transformative investments including the Pay Equity Fund and DC Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). She also proposes vastly scaling back DC’s “baby bonds” program, a first-of-its-kind in the nation investment aimed at reducing racial income and wealth gaps. Her proposal also backtracks on commitments to housing affordability, rental assistance, and ending homelessness, and it forces schools to cut staff and swipes funds for environmental justice. As is, the proposed budget will set back the progress that DC has made on poverty reduction, greater economic inclusion, and shared prosperity.

While the mayor does propose to raise revenue, one of the major proposals is increasing the sales tax, which disproportionately harms residents with low and moderate incomes. Combined with the backtrack on the EITC, the mayor’s tax proposals would, on net, raise the effective tax rate on DC’s residents with the lowest incomes relative to where it would otherwise be.

DC Council does not have to follow suit. Instead, DCFPI urges the Council to consider budget shifts and the overlapping revenue proposals from DCFPI, the Just Recovery DC Coalition (JRDC), and the Fair Budget Coalition—many of which stem from analysis of the Tax Revision Commission (TRC). These proposals fulfill several goals—they 1) raise revenue to keep promises to residents, 2) improve progressivity and equity, and 3) fortify our revenue system for the longer term. These proposals include:

- Making strategic budget shifts. The DC Council should reject the mayor’s proposed downtown property tax breaks for developers converting downtown offices to other uses, such as hotels and restaurants, costing $7 million a year by FY 2028 and $20 million a year by FY 2030. Council should also repeal the Housing in Downtown expansion in FY 2028, which increases this tailor-made tax break for developers from nearly $7.1 million in FY 2027 to $41 million in FY 2028 and continues to increase its cost by 4 percent each year after. Lawmakers should provide proof that this program is meeting its intended goals before quintupling its size.

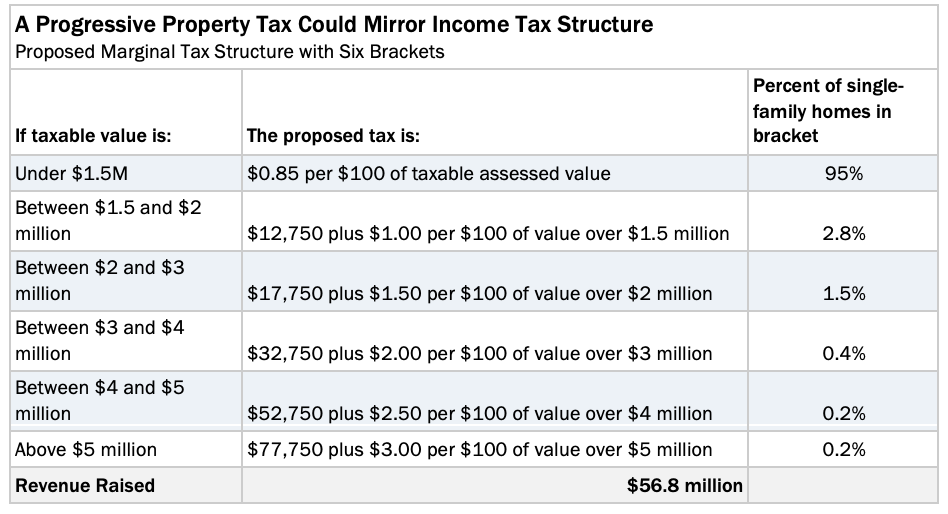

- Raising property taxes on high value homes. DC can raise taxes on homes with taxable value above $1.5 million, affecting only 5 percent of homeowners, by introducing a marginal property tax rate structure on single family homes. DCFPI’s proposal would index the tax to the 95th percentile of home values in perpetuity, and it would exclude homeowners receiving exemptions or credits for low income or for seniors, veterans, or people living with a disability.

- Raising taxes on households with the highest incomes. DC can limit itemized deductions as proposed by the TRC and JRDC, dialing back a tax break that primarily benefits DC’s highest income households. It also can raise marginal rates on income above the $500,000 or million-dollar thresholds.

- Raising the capital gains tax rate. DC can strengthen its taxation of capital gains income, a major form of wealth accumulation for those with substantial wealth. In 2020, for example, 71 percent of net capital gains income accrued to the top 1 percent of DC filers who reported $1 million or more in federal adjusted gross income. This is an even greater share than in the US as a whole.[1]

- Restoring the EITC expansion and rejecting the sales tax increase. The cut to the EITC expansion would reduce the benefit to a single working parent with three children by $2,230 compared to full implementation. This and the sales tax increase proposed by the mayor will raise the effective tax rate for DC’s low- and moderate-income working families. Council should reject both proposals.

- Adopting a Child Tax Credit (CTC) and expanding Schedule H. DC Council can boost low- and middle-income households through a local CTC and expansion of Schedule H. Lawmakers can design a local CTC to reach residents with middle incomes to help with the costs of raising children and reduce the overall amount of taxes they pay. Likewise, an updated property tax credit, as proposed by the TRC and JRDC, would reach homeowners with incomes up to $100,000 and renters with incomes up to $85,000, reducing what they pay in property taxes.

- Laying the groundwork in the Budget Support Act for FY 2025 implementation of a Business Activity Tax (BAT) within the financial plan. The TRC devised a proposal for a New Hampshire-style value-added tax for DC that would expand DC’s tax base, circumventing federal limitations on taxation of non-resident owners of pass-through businesses, thereby making the revenue system more resilient and fairer. DC can firm up its estimate of how much the BAT would raise and prepare businesses for the transition by having businesses fill out a “ghost” form to assess their liability prior to actual implementation.

- Laying the groundwork to adopt a split rate tax on commercial and residential property as a more sustainable and productive way to tax land and property. Like with the BAT, the TRC explored various ways to bring taxation of land into DC’s tax code, alongside property. DC can both encourage the highest value use of land and better target land and property taxes to meet specific needs, like funding of public transportation, through a split rate tax on land and property.

Mayor’s Budget Slashes Programs for Poor and Working Class, But Council Should Make Better Choices

The mayor made the “tough choice” to slash District spending on programs and services that support residents facing economic hardship, while maintaining or enhancing investments elsewhere, contradicting the notion of “shared sacrifice.” DC Council can and should make better choices.

DCFPI urges the Council to consider budget shifts and also the overlapping revenue proposals from DCFPI, JRDC, and the Fair Budget Coalition—many of which stem from analysis of the TRC. These proposals fulfill several goals—they 1) raise revenue to keep promises to residents, 2) improve progressivity and equity, and 3) fortify our revenue system for the longer term.

Raise Property Taxes on High Value Homes[2]

DC can make the residential property tax structure more progressive by splitting District properties into value brackets, each with a progressively higher marginal rate. Raising taxes on homes with taxable value above $1.5 million would impact only 5 percent of homeowners. (Note: many homeowners do not pay taxes on the full assessed value of their homes, which the District assigns based on a range of characteristics, such as size and condition of the building. The assessment is the starting point for a property owner’s tax liability, but deductions and credits may reduce the taxable value of a property.) DCFPI proposes indexing the threshold for higher rates to the 95th percentile of home values to ensure that the target remains the top 5 percent of homes over time. Lawmakers can protect seniors and homeowners with low incomes by excluding homes where the homeowner receives a homestead-based deduction or credit for seniors, people living with disabilities, veterans, or residents with low incomes.

Depending on the number of property value brackets and rates, a marginal property tax rate structure could raise around $57 million (Figure 1).

Raise Taxes on Households with the Highest Incomes Through Rate Increases[3]

DC can limit itemized deductions, a tax break that primarily benefits DC’s highest income households, and raise rates on incomes above the $500,000 or million-dollar thresholds. The TRC analyzed both ideas and included in a draft package of proposals for the mayor and Council the limitation on itemized deductions. The proposals were to:

- Increase the phaseout rate on itemized deductions from 5 percent to 7.5 percent. This would raise an estimated $26 million. Council could adopt this proposal or go further and increase the phaseout rate to 10 percent to raise twice that to restore funding for critical programs.

- Replace the top two marginal income tax rates with three rates: 10 percent on incomes between $500,000 to $1 million; 11 percent on income between $1 to $5 million; and 12 percent on income over $5 million. This would raise $60 million to $70 million annually.

Raise the Capital Gains Tax Rate and Eliminate Loopholes that Protect and Further Concentrate Wealth

One equitable way to raise revenue to keep critical programs and services whole and close the racial wealth gap is by taxing DC’s outsized concentration of wealth. In DC, 0.4 percent of households, or roughly 1,500 households, have net worth over $30 million and hold half of all the wealth in DC, to the tune of $183 billion. A sizeable share of this is held in unrealized capital gains.[4]

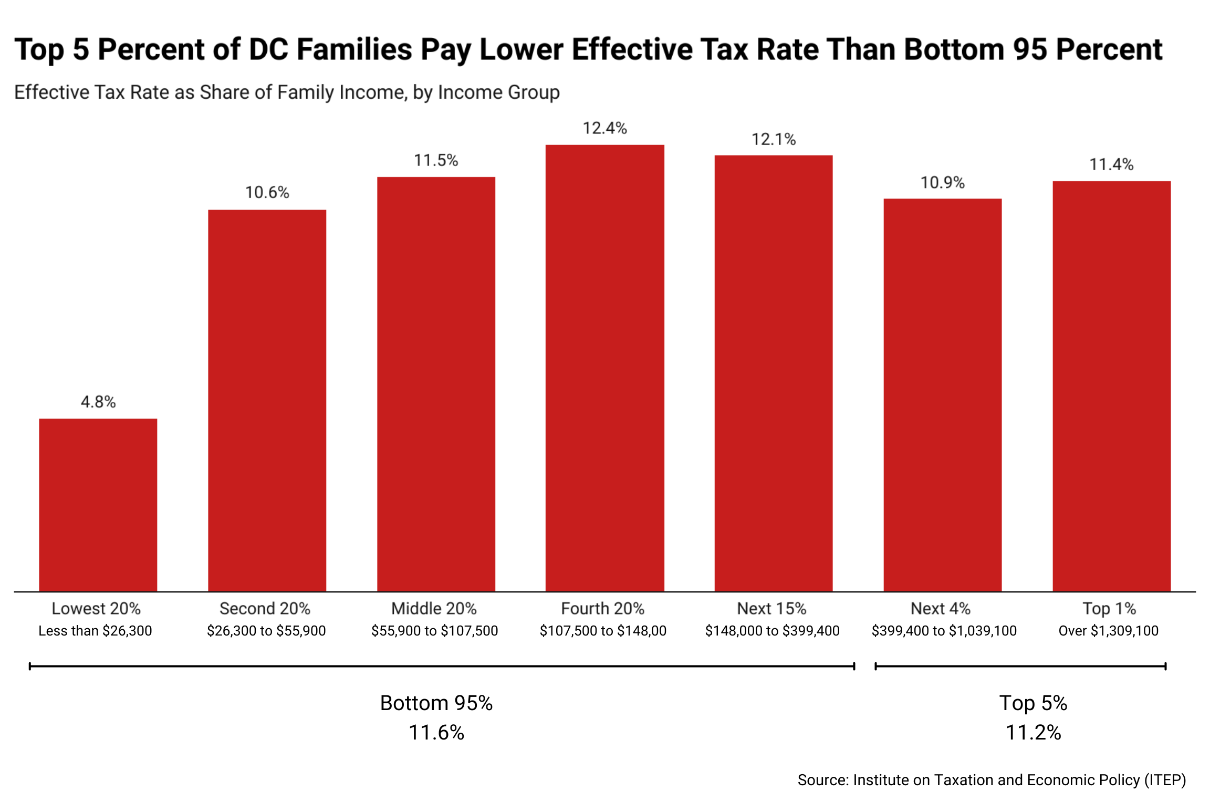

The federal and DC governments tax income from wealth more favorably than income from work, particularly capital gains income, which benefits very wealthy, white households the most.[5] This advantage contributes to the reality that DC’s tax code still favors the top 5 percent, and in the DC area white households have 81 times the wealth of Black households (Figure 2).[6] Racial justice requires unrigging this system, and taxing wealth more heavily, to build a future of shared abundance.

While DC taxes capital gains income at the same rate as income from work, it still allows the wealthy to defer paying taxes on appreciating assets for years and sometimes decades until they are sold and exempts a lifetime of untaxed capital gains income upon death, costing the District tens of millions a year. DC should consider taxing capital gains separately from ordinary income and at a higher rate for taxpayers in the top 20 percent of incomes, along with eliminating the stepped-up basis for capital gains bequeathed at death.[7]

Like wealth, capital gains income disproportionately accrues to high-income, white households. In 2020, for example, less than 1 percent of DC filers reported $1 million or more in federal adjusted gross income, but those filers claimed 71 percent of net capital gains income in the District. This is an even greater share than in the US as a whole.[8] By design, tax advantages for capital gains accrue to a narrow share of wealthy, high-income households, exacerbating income, wealth, and racial inequality. Taxing capital gains would both help correct this inequity and raise revenue for a more balanced budget.

DCFPI recognizes that because of the DC housing market, in which some longtime homeowners may find their homes rapidly appreciating, that wealth accumulation may inadvertently push some households into higher capital gains tax rates. As such, DCFPI is preparing proposals for holding the bottom 80 percent of incomes (as well as low and moderate-income heirs of property) below a certain threshold of gains.

Restore Planned Increases to DC’s EITC and Reject the Sales Tax Increase

Restore the EITC Expansion

The mayor’s budget eliminates planned increases in DC’s EITC, reducing the income boost for more than 39,000 families with low and moderate wages by nearly $70 million over the financial plan.[9] Council has expanded this credit over time because it makes a big difference in the lives of workers and their children, helping them keep more of what they earn and meet basic needs like rent and food. It is a powerful tool for advancing racial, gender, and economic equity—and is a major reason DC has the least regressive tax code in the nation.[10] The credit:

- Helps working families—especially those with incomes between $10,000 and $30,000—meet basic needs, like paying for food, bills, transportation, and child car[11].< Nearly 13 percent of families with children and 21 percent of single mother families with children in DC lived below the official poverty line in 2022 (about $31,200 for a single parent family of four).[12] Many more DC families that live modestly above that income level also have difficulty affording necessities. Meeting these needs helps parents keep working and may help them stay employed until better opportunities arise.

- Improves racial and gender equity. Black and brown residents—especially women—are disproportionately likely to be in low wage work and eligible for the EITC. In fact, nearly seven in ten eligible EITC filers in DC are Black and about that many EITC filers or their spouses are women.[13] The credit also goes a long way in helping single parents, who are likelier to be women of color, and research shows it can improve the earnings record of women, resulting in larger Social Security benefits upon retirement.

- Has a lasting effect. Research finds that young children in families with low incomes that get a cash boost like that provided through the EITC tend to do better and go further in school, and work and earn more as adults, likely because the additional resources help parents better meet their needs. Children of color are even more likely to see these improvements.[14]

Under current law, DC will match 100 percent of the federal credit by 2026, up from the current 70 percent match, making it the most generous credit in the nation. The mayor’s budget would freeze DC’s EITC at 70 percent, leading to a profound decrease in income for eligible workers compared to what’s been promised. An eligible worker with three kids would see their maximum DC credit go down by approximately $2,230 compared to full implementation in 2026 (using tax year 2023 EITC maximum credits).[15]

While the mayor’s budget raises over $1 billion in revenue, one of the major proposals is increasing the sales tax, which disproportionately harms residents with low incomes. Combined with the EITC backtrack, these proposals would, on net, raise the effective tax rate on DC’s residents with the lowest incomes relative to where it would otherwise be.

DC Council should restore funding to the DC EITC and ensure that the budget doesn’t raise taxes on residents already struggling to get by. The Council should also allow EITC filers to opt out of monthly payments, given it can put receipt of federal benefits, especially food assistance, at risk—a protective measure even more important in a context of deep cuts to human services.[16]

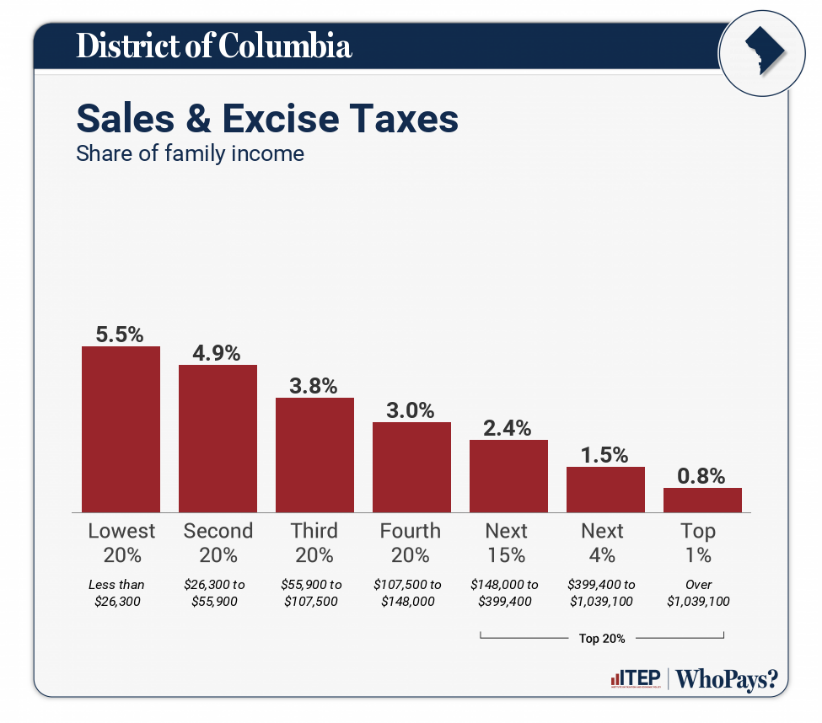

Reject Proposed Sales Tax Increase

DC Council should also reject the sales tax increase proposed by Mayor Bowser. Sales taxes are regressive, meaning they ask the most as a share of income from the households with low and moderate incomes. DC’s lowest income households currently spend on average 5.5 percent of their incomes on local sales and excise taxes, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (Figure 3).[17]

Combined with the cut to the EITC expansion, the sales tax increase will raise the effective tax rate—all taxes paid as a share of income—for DC’s lowest income families (those in the bottom two-fifths of the income distribution, or $0 to $55,900) relative to where it otherwise would be under current law.

Adopt a Local Child Tax Credit and Expand Schedule H

DC can improve progressivity and racial equity with two tax credits aimed at low to middle income households.

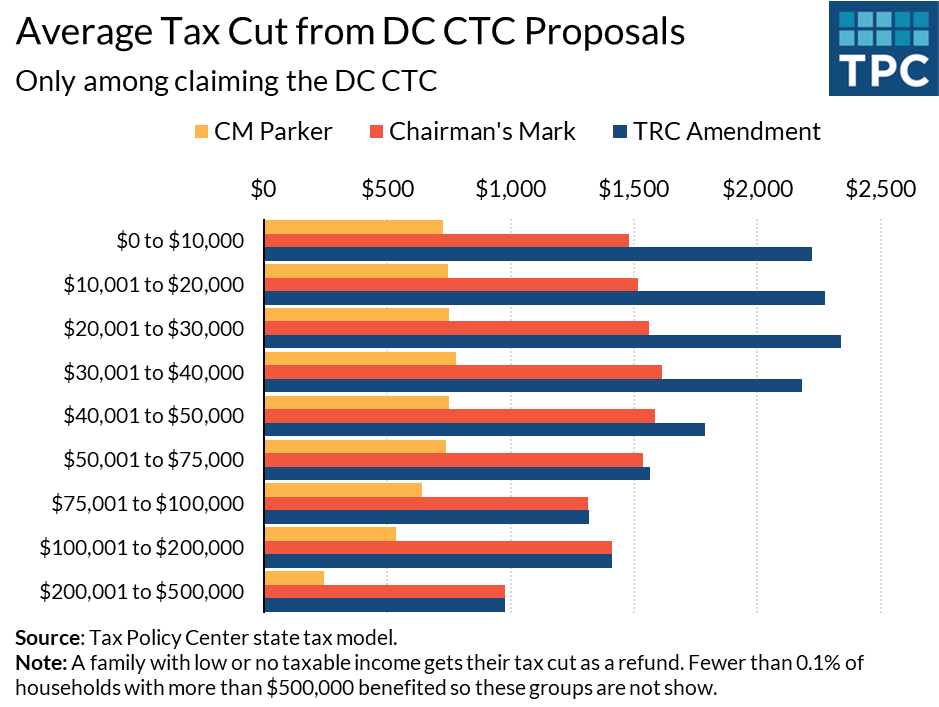

DC should enact a local CTC that takes aim at reducing child poverty in DC and boosts middle income families, too. In DC, more than one in three Black children live in a family below the official federal poverty line and analysis conducted for DCFPI finds that a DC CTC set at $1,500 per child would reduce child poverty by 18 percent.[18]

The District can also boost middle income families by reducing the taxes they pay with a local CTC. DCFPI’s proposal would reach families with incomes up to 300 percent of the federal poverty line, with nearly 90 percent of the benefit going to families with incomes below $104,000. Councilmember Parker and the TRC also have CTC proposals that reach the middle-income households, with the TRC proposal also reaching high income households (Figure 4).

The TRC also proposed (and JRDC adopted to its platform) an expansion to Schedule H, DC’s property tax credit for low- and moderate-income households.[19] This proposal would raise the income at which households can receive the credit to $100,000 for homeowners and to $85,000 for renters (up from $78,000 for seniors and $58,000 for non-seniors). The proposal would raise the cap on the credit to ensure those eligible did not spend more than 2 percent of their income on property taxes.

Both credits, as envisioned above, would go a long way to helping DC achieve its goals of progressivity and equity.

Broaden the Tax Base and Make Business Taxes Fairer[20]

DC can adopt a BAT to ensure that all businesses that benefit from the District’s economy are contributing to its tax base. A BAT would allow the District to circumvent federal limitations on the taxation of non-resident incomes. Since many businesses in DC are organized as pass-through entities—those in which profits are passed through to owners and taxes paid via the income tax—many do not pay anything into DC’s business tax base. The Unincorporated Business Tax (UBT) helps DC tax some pass through entities but those primarily delivering professional services, like lobbying, legal, and accounting firms, are exempt.

The Tax Revision Commission studied this idea in depth and proposed a low-rate BAT that replaces the unincorporated business franchise tax and is set as a credit against the corporate franchise tax. At a rate of 1.9 percent, and with the repeal of the UBT, the BAT would generate $300 million in new revenue. That rate can be scaled up or back depending on desired revenue generation.

While lawmakers cannot implement the BAT immediately to shore up funding in the FY 2025 budget, they can and should implement it within the financial plan. One way to aid in effective implementation of the BAT is to create a “ghost form” for the BAT that businesses would fill out using the data on their federal tax forms. This would give the Office of Tax and Revenue a better understanding of how much revenue it would generate and businesses themselves a better sense of what the tax would mean for their liability to DC.

Implement a Split Rate Tax on Commercial and Residential Property[21]

The 2023 and 2013 DC Tax Revision Commissions explored creating a more equitable property tax structure by valuing land and the improvements to it separately and, in parts of the District where land is more valuable, taxing it at higher rates. Land is more valuable in the District’s most commercially vibrant and transit-accessible neighborhoods than the physical properties on it, and that land should be taxed accordingly. DCFPI encourages the exploration of a geographically targeted land tax on commercial and residential property that is supplemental to the current tax structure. A “split-rate” structure should be coupled with reductions to property tax levels in neighborhoods with less economic investment.

DC can both encourage the highest value use of land and better target land and property tax to meet specific needs. For example, DC could tax the land around metro stations at higher rates to raise dedicated funds for WMATA over the long-term, like funding of public transportation.

The TRC commissioned research from Nick Allen, former Manager of Strategy and Policy at the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation, to analyze what a split rate system could raise in DC. The estimates show that a $0.31 per $100 of land value on top of existing property tax rates could raise $300 million annually.

[1] Tazra Mitchell, “Taxing Capital Gains More Robustly Can Help Reduce DC’s Racial Wealth Gap,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, October 31, 2023.

[2] Eliana Golding, “DC Can Advance Racial Equity and Black Homeownership through the Property Tax,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, October 17, 2023.

[3] See “Raise tax rates on high-income earners,” and “Limit itemized deductions,” DC Tax Revision Commission, 2023.

[4] Carl Davis, Emma Sifre, and Spandan Marasini, “The Geographic Distribution of Extreme Wealth in the U.S.: Estimating Wealth Levels and Potential Wealth Tax Bases Across States,” Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), October 2022. And, data provided by ITEP to DCFPI in October 2022. Data reflects ITEP’s Microsimulation Tax Model analysis, using data from the Internal Revenue Services, Survey of Consumer Finances, Forbes, and other sources. Ultra wealthy includes those with wealth of at least $30 million.

[5] Mitchell, 2023.

[6] Erica Williams and Nikki Metzgar, “Top 5 Percent of DC Earners Pay Lower Share of Income in Taxes than Bottom 95 Percent,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, January 9, 2024.

[7] For more details on these proposals, see: Mitchell, 2023.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Office of Revenue Analysis, “Review of Income Security and Social Policy Tax Expenditures,” Office of Chief Financial Officer, August 2021, page 31.

[10] Williams and Metzgar, 2024.

[11] Office of Revenue Analysis, “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” December 2020.

[12] US Census Bureau, “2022: ACS 1-Year Estimates Data Profiles for DC,” accessed April 22, 2024.

[13] CBPP 2019 estimates prepared using Urban Institute’s Analysis of Transfers, Taxes, and Income Security microsimulation model and American Community Survey data via IPUMS USA.

[14] Chuck Marr, et al., “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds,” CBPP, October 1, 2015.

[15] For example, in tax year 2023 the maximum federal EITC for a parent with 3 or more children is $7,430; 70 percent of that maximum credit equals $5,201, about a $2,230 difference.

[16] Tazra Mitchell, “District Must Make Changes to EITC Payments; Prioritize Funding for Baby Bonds,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, February 13, 2024.

[17] “Who Pays? State-by-State Data,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 2024.

[18] Erica Williams, “A Child Tax Credit Would Reduce Child Poverty, Strengthen Basic Income, and Advance Racial Justice in DC,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, March 6, 2023.

[19] DC Tax Revision Commission, “Expand and consolidate means-tested property tax relief programs,”2023.

[20] Memo to DC Tax Revision Commissioners by TRC staff, “Business Activity Tax chairman’s mark and possible amendments,” January 5, 2024.

[21] See: DC Tax Revision Commission, “Tax land and buildings at different rates,”2023, and Nick Allen, “Land Value Taxation for Equitable Growth,” Presentation to the DC Tax Revision Commission, 2023.