Parents need accessible, affordable child care to work, go back to school, and to ensure their children are receiving the care they need to develop. Research has shown that high-quality child care and early education programs lead to long-term learning and development benefits for children. But DC has the highest costs for child care compared to the rest of the country, with families paying over $23,000, on average, per year to enroll their children in infant care.[1]

DC’s child care subsidy program helps nearly 7,700 families with low and moderate incomes pay for the cost of child care.[2] The subsidy program is an avenue for predominately Black and brown parents—who have faced centuries of systemic oppression—to give their children a jumpstart on their education and to have a safe and supportive environment for their children while they work or pursue an education.

However, only half of child development facilities (CDFs) in the District participate in the subsidy program due to a variety of barriers and financial concerns. This limits the subsidy program’s ability to connect families with child care providers that meet their needs and provide affordable care, reducing the program’s overall reach and effectiveness.

Expanding the supply of child care providers who participate in the subsidy program is necessary to ensure that every family with a subsidy has access to a center or home where they can use it. Therefore, it is critical to understand what might be keeping child care directors and owners from expanding the number of children receiving subsidies that participate in their programs or from accepting child care subsidy at all.

From August to September 2024, the DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI) surveyed 79 child care providers in DC and interviewed a subset of respondents in focus groups to better understand barriers to participating in the subsidy program. Data from both the focus groups and surveys pointed to five areas of improvement for the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) to make the child care subsidy program more accessible and efficient:

- Make it easier for directors to apply to participate in the subsidy program by increasing staff support at OSSE for directors who are applying, developing a network of directors who can provide peer support through the process, and encouraging directors to apply for the subsidy program immediately after receiving their license to operate.

- Increase reimbursement rates so that they meet the true cost of care, especially for categories where demand is the highest, like for infant and toddler care. Also, switch to paying facilities prospectively rather than retrospectively, as is now required by the federal government.

- Streamline data systems and reporting requirements. Currently, child care providers who offer subsidy have to submit paperwork—often the same paperwork—to multiple systems, which can be overwhelming, time consuming, and can cause confusion and errors. If OSSE created a single portal where providers could submit documents once and have visibility into how and when paperwork is processed, it would ease administrative burdens that keep some providers out of the system entirely.

- Increase the number of child care facilities that can determine family eligibility for the child care subsidy program by expanding who can become a Level II provider.

- Improve OSSE communication with child care providers by offering more frequent training sessions on becoming a subsidy provider, hiring more Help Desk staff to answer questions and walk providers through complicated processes, and ensuring that there is bilingual staff available to assist providers in an accessible way.

Child care providers’ experiences with the subsidy program offer OSSE and other policymakers a better understanding of the barriers they face and a range of steps for improving all parts of the process to encourage greater participation and expand options for District families. By heeding their recommendations to improving the processes by which child care directors can enter and interact with the child care subsidy program, OSSE would encourage existing subsidy providers to increase the number of families they serve through the subsidy program and encourage new child care providers to do the same, thus growing the supply of affordable child care to meet the demand from District parents.

Table of Contents

- DC’s Subsidy Program is an Avenue to Affordable Child Care with Long-Lasting Benefits, But Barriers to Participation Limit Effectiveness

- OSSE Should Streamline the Program’s Application Process and Improve Support to Providers

- OSSE Should Increase Reimbursement Rates to Reflect the True Cost of Providing Child Care

- OSSE Should Streamline Data Systems and Reporting Requirements to Reduce Administrative Burden on Providers

- To Advance Racial Equity, OSSE Should Increase the Facilities that Can Determine Family Eligibility

- OSSE Should Improve Transparency and Communication with Child Care Providers

- Additional Policy and Administrative Changes Needed to Build the Child Care System Families Deserve

- Acknowledgements

DC’s Subsidy Program is an Avenue to Affordable Child Care with Long-Lasting Benefits, But Barriers to Participation Limit Effectiveness

Research has shown that high-quality child care and early education programs provide safe and enriching environments that support the development of children’s language and social-emotional skills.[3] Children’s experiences during this time also play a vital role in shaping their long-term learning and development, underscoring the importance of ensuring access to quality early learning opportunities for young children.[4]

The District’s child care subsidy program makes child care more affordable for families with low and moderate incomes. The program ensures that no eligible family pays more than 7 percent of its income on child care when using a program voucher, with most parents paying less than $11 per day in co-pays and many paying $0. DC recently expanded access to the subsidy program to families with higher incomes, acknowledging that investing in affordable, high-quality care can facilitate economic gains for Black and brown families, small and large businesses, and the DC economy as a whole.[5]

While this program provides valuable support, parents and providers face barriers to participation that can limit its effectiveness. In DC, families earning up to 300 percent of the federal poverty rate ($93,600 for a family of four) are eligible to participate in the subsidy program if they meet additional requirements, such as being in an eligible education or work program or engaged in a job search. There are more than 40,000 children in DC living in households that meet the income eligibility requirement, but less than 20 percent of those children made use of child care subsidies in fiscal year (FY) 2023.[6]

Parents often face challenges when trying to obtain and use subsidies, such as finding care providers that accept vouchers and meet their standards. DC NEXT!, a federally funded collective impact innovation network aimed at improving the health and well-being of expectant and parenting teens in the District, interviewed a young parent regarding this issue who said, “The child care that I wanted, I couldn’t have. I really wanted them to go to the one that had more learning things and activities they can do… It was just so expensive. I was just like… hopefully by next year, they can accept vouchers. They put me on a waitlist. That would have been $1,300 per month. I can’t afford that and rent and a car.”[7]

The effectiveness of the child care subsidy program depends on the participation of child care providers. All licensed CDFs in the District are eligible to participate in the subsidy program, but only half of CDFs participate due to a variety of barriers and fiscal concerns for operating their facilities.[8] Because there is a shortage of high-quality child care providers that accept subsidy vouchers, parents find it difficult to find quality and affordable options.[9]

The fact that there are more subsidy vouchers available than being used stems from DC’s declining population (i.e., lower demand), changes to commuting patterns, as well as an increasing mismatch between supply and demand for certain age groups and the location of that care in the District.[10] Demand for subsidized infant and toddler seats outpaces the supply by over 3,000 seats, according to a recent supply and demand study commissioned by the Bainum Foundation.[11] The deficit of seats is even larger for care during non-traditional hours and care offered in languages other than English. These issues underscore the need for improvements to ensure the program better serves families.

OSSE and District elected officials have shown a commitment to improving the child care subsidy program for both families and providers. In the past two years, they have:

- Expanded eligibility for families (from 250 percent of the federal poverty line to 300 percent);

- Put the subsidy application for parents online, shortening the time it takes to review applications;

- Raised reimbursement rates (and have begun to reduce the difference in reimbursement rates by quality level); and

- Switched to paying providers based on enrollment rather than attendance.

These changes have increased the utilization of child care subsidies, particularly among families with infants and toddlers, but further improvements will be needed to expand provider participation and create a well-functioning child care subsidy system.

Child care providers’ experiences with the subsidy program offer important insights into the challenges of participation and help point to solutions that are grounded in and responsive to their realities. DCFPI conducted a survey and focus groups for this report that point to steps that OSSE can take to improve the program, and thereby the access to quality care for families and children with low incomes. The full methodology of DCFPI’s 2024 Child Care Directors Subsidy Survey is available in Appendix 1.

OSSE Should Streamline the Program’s Application Process and Improve Support to Providers

When someone wants to open a licensed child care facility in DC, they must submit documentation that they’ve fulfilled certain requirements, such as attending a licensing orientation, providing proof of insurance and alignment with safety requirements, and checking the criminal background and qualifications of all staff.[12] After that person receives a license to operate a center or home, they can begin the application process to participate in the subsidy program.

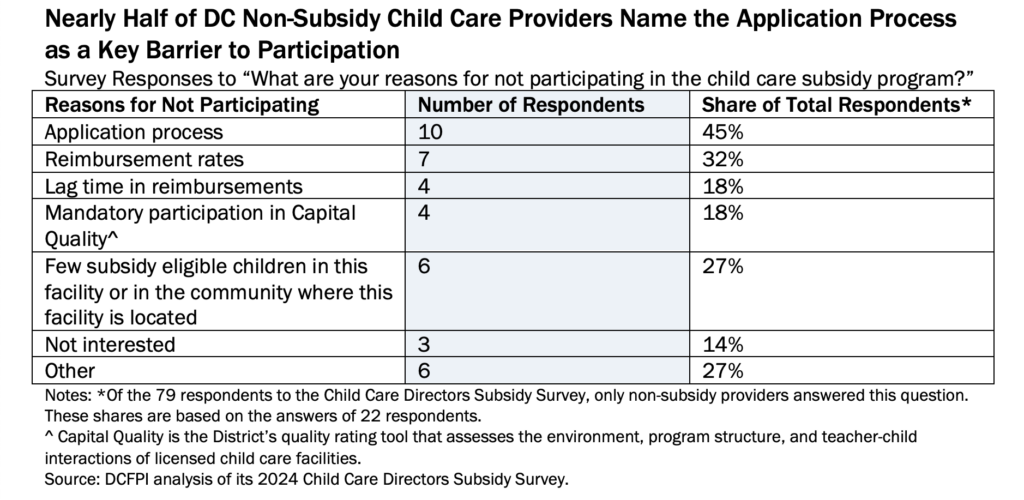

The application to participate in the subsidy program primarily focuses on meeting the necessary standards to receive government funding. CDF directors hoping to participate in the child care subsidy program must submit various tax documents, have their staff complete non-disclosure agreements, ensure the right level of insurance, and adopt an OSSE-approved curriculum, among other requirements, in order to qualify. Almost half of the 22 non-subsidy providers surveyed by DCFPI named the application process as a reason for not participating. Table 1 provides a full breakdown of the reasons providers gave to the question of why they do not participate.

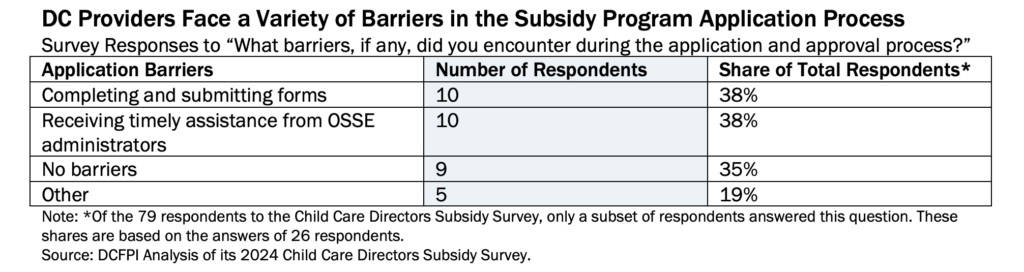

The survey also asked non-subsidy and subsidy directors about the specific barriers they encountered during the application process. Table 2 provides a breakdown of their responses, showing that among those who responded, more than one-third identified completing and submitting forms as a primary barrier, and the same percentage of respondents stated that receiving timely assistance from OSSE administrators was a barrier. One respondent highlighted the need for Spanish-speaking assistance during the subsidy application process.

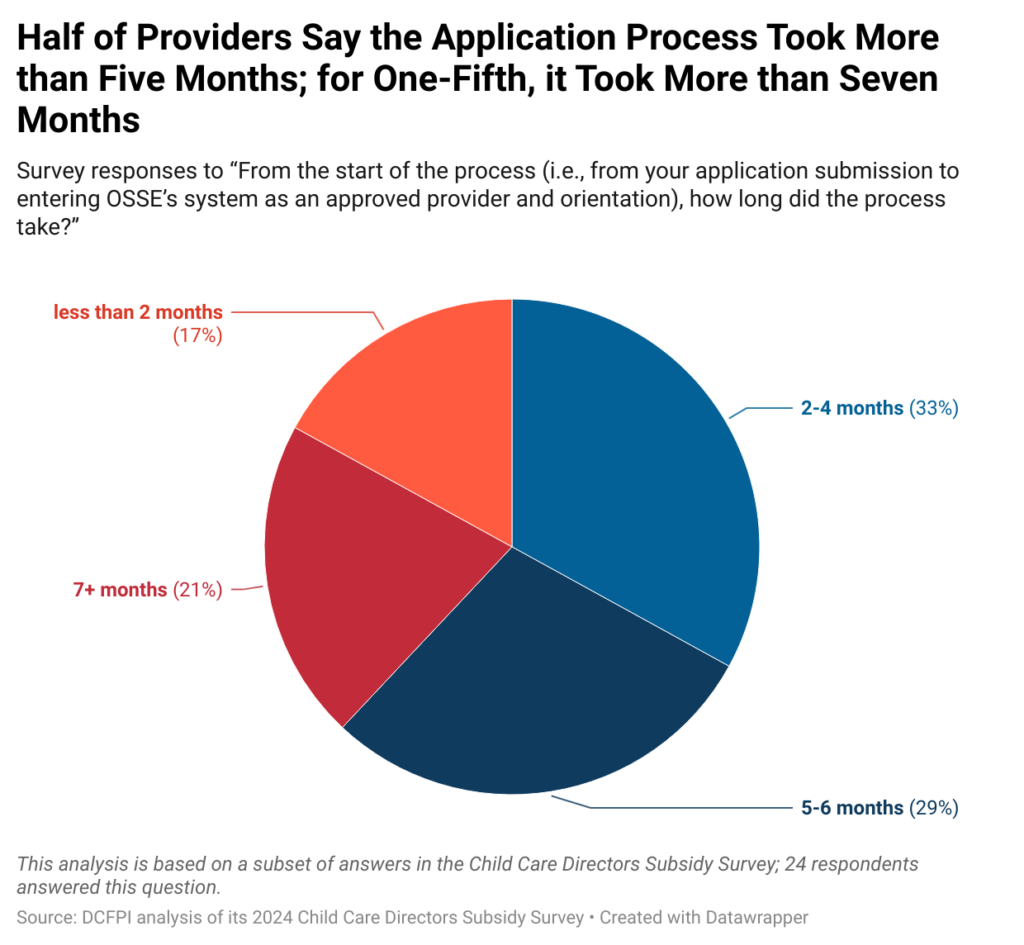

Directors also highlighted the long wait time during which OSSE processes the application—what some directors refer to as the “quiet period”—as a major barrier to entering the program. Figure 1 shows how long the application process can take.

In focus groups, some directors described submitting the subsidy application and waiting for weeks to hear back from OSSE, only to be told that there was an error with their application. These directors reported that by the time they were able to fix the error, the entire process had been delayed, which negatively impacted the recruitment of families into their program.

Increasing dedicated support staff with relevant child care experience to help CDF directors through the application process would reduce the burden for directors and the chance for errors. It is especially important to hire staff who speak Spanish or Amharic, the primary languages besides English spoken in DC.[13] Hiring more support staff also would allow OSSE to review and approve applications more quickly so that directors can offer open slots to subsidy families in their communities more quickly. OSSE currently offers regular office hours to answer questions about the subsidy application process, but these office hours are not widely utilized by providers and, for those who do use them, are not sufficient to resolve providers’ issues, according to survey respondents. OSSE should conduct outreach to better understand why directors and owners are not tapping into this resource during the application process.

One director recommended creating a support network that pairs directors who recently completed the application process with those who have yet to complete it to provide insights and assistance with the process. This initiative could be supported through existing coalitions or philanthropy.

Finally, some directors suggested that OSSE combine the application for licensing with the application for the subsidy program. However, combining the processes would not change federal requirements and may make getting licensed more onerous. Instead, OSSE should consider encouraging directors to apply for subsidy immediately upon approving them for licensing because it requires much of the same information. Moreover, OSSE’s subsidy application system could be refined to automatically pull into the subsidy program application any required information already provided during the licensing application.

OSSE Should Increase Reimbursement Rates to Reflect the True Cost of Providing Child Care

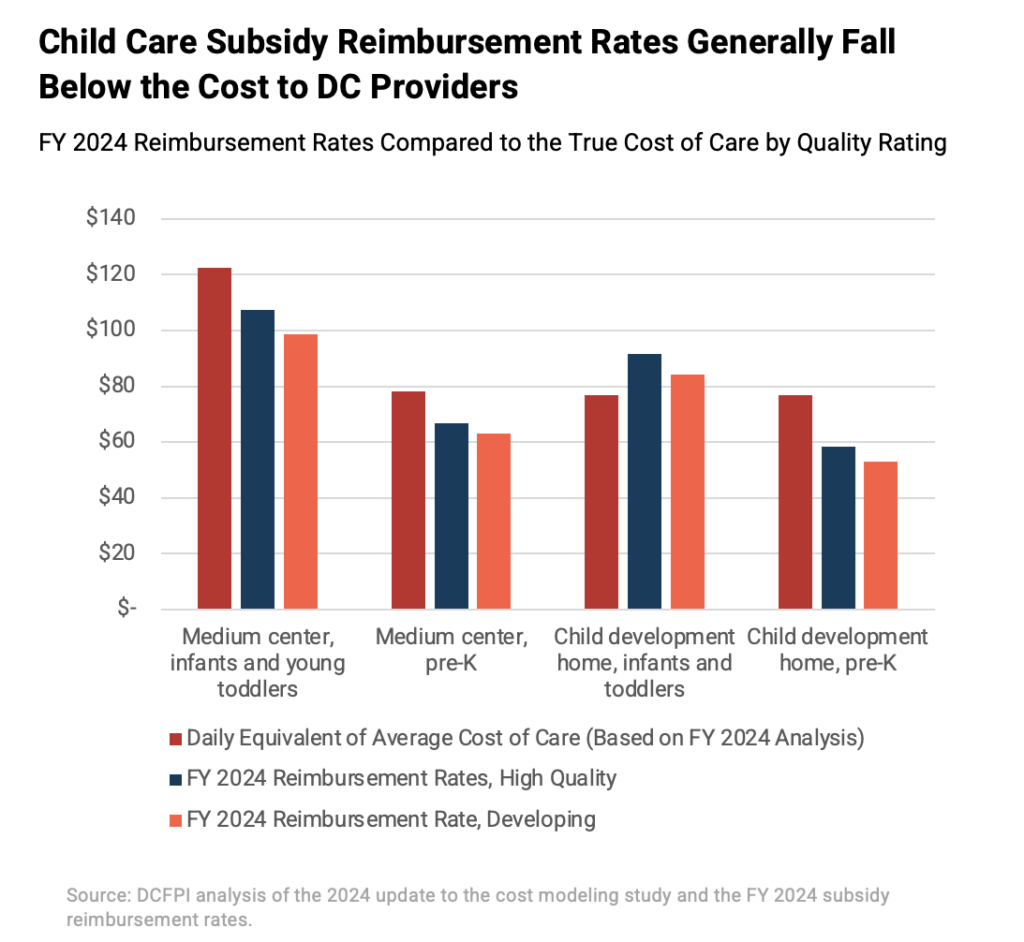

Reimbursement rates—or the monetary value of child care vouchers—vary based on the age of the child, whether a child attends a facility part- or full-time, the type of facility (center or home), and the quality rating of the facility. In addition, the federal government allows local agencies to set reimbursement rates based on a market rate survey or cost-of-care modeling. DC has among the highest reimbursement rates relative to other states across the country, largely because it is one of the first states to base its rates on the actual cost of operating a child care facility through a “True Cost of Care” study.[14],[15] Since the adoption of the Birth-to-Three for All DC Act in 2018, OSSE is required to model the true cost of care every three years to determine reimbursement rates.

“I was told that the reimbursement rate would be so low it wouldn’t make sense to participate.”

The True Cost of Care model takes into account the variety of cost drivers in a child care center or home. These include wages and benefits—the primary driver—as well as adult-to-child ratios, the cost of supplies and supplemental services, and other expenses associated with licensing and compliance with local and federal laws.[16] Generally speaking, these studies have found that it costs more to operate a center versus a home-based program because of additional staff positions and increased overhead costs. In either setting, it costs more to serve infants and toddlers versus older children primarily due to lower adult-to-child ratios.

OSSE has completed five cost modeling studies since 2016 and raised reimbursement rates as these studies show increasing costs over time. However, reimbursement rates still lag behind the true cost of care with the exception of the rate paid to child care homes serving infants and toddlers.[17] In all other categories, reimbursement rates are 14 to 45 percent below the true cost of care (Figure 2).[18] OSSE can only raise reimbursement rates when the overall budget for the child care subsidy program is sufficient to cover the increased cost. Since OSSE raised reimbursement rates in 2023, lawmakers have cut the subsidy budget, so OSSE has kept reimbursement rates flat despite the increasing operational costs to facilities.

Respondents to the survey identified inadequate reimbursement rates as a primary reason for not participating in the subsidy program (Table 1). One respondent said, “I was told that the reimbursement rate would be so low it wouldn’t make sense to participate.”

Subsidy providers are also required to participate in Capital Quality, an observation-based quality rating and improvement system that measures and reports the quality of licensed child care facilities in the District and designates them as developing, progressing, quality, or high quality. In both the survey and focus groups, many providers expressed that the Capital Quality tool does not always accurately assess the true quality of services. For example, by default, all facilities are designated as “developing”—the lowest quality rating—when first licensed, regardless of actual quality. Providers are stuck with this designation for one year until they receive their first actual assessment. OSSE should consider designating newly participating facilities as “new” or “not yet assessed” rather than “developing” to make this distinction clearer to families seeking care.

These quality ratings are not simply a matter of pride. Importantly, they impact the rate at which facilities are reimbursed for subsidy: facilities with higher quality ratings receive higher payments and those with lower ratings receive lower payments. Not only have child care directors and advocates flagged this approach as misguided, but findings from the 2024 cost modeling study reveal that the factors measured by Capital Quality do not drive costs one way or the other.[19] In recognition of this fact, OSSE has started to reduce the difference in reimbursement rates between designated quality levels, but at this time, facilities rated as lower quality continue to receive lower reimbursements than those rated as higher quality.

OSSE should continue to raise reimbursement rates as operational costs increase and ensure that facilities across all quality designations have the funding needed to deliver high-quality care and education. If the child care subsidy program budget cannot fully fund across-the-board increases to reimbursement rates, OSSE should increase rates based on the type of care that is most in demand, like care for infants and toddlers. This could allow existing subsidy providers to care for a greater number of infants and toddlers receiving child care subsidies and encourage providers who do not currently accept subsidy to enter the system because they would benefit from consistent payments that meet the cost of providing care.

OSSE should also pay subsidy providers prospectively rather than retrospectively for their enrollment. In focus groups, directors expressed that they experience delayed payments from OSSE due to lag times in correcting errors to attendance and enrollment reports. As a result, providers have kept children enrolled without a reimbursement guarantee, which can result in running their businesses at a loss. The federal government is now requiring that states switch to a prospective payments model, but this change will take some time to implement due to infrastructure needs and budget constraints.

OSSE Should Streamline Data Systems and Reporting Requirements to Reduce Administrative Burden on Providers

“If you are not business savvy or if you don’t do your own taxes, don’t expect to be able to fill out a subsidy form.”

Child care providers often cobble together funding from a variety of public and private sources in order to operate, which means they report to a variety of agencies on their operations. This can create a tremendous administrative burden for child care providers to maintain funding. For example, when providers become licensed, they must submit and manage staffing information on credentials, background checks, and other educator requirements in the DC Division of Early Learning Licensing Tool. When a provider initially applies to the child care subsidy program, they submit documents to the BOX, the online system used by OSSE to collect supporting documents for facilities’ subsidy applications. All subsidy providers submit monthly attendance reports in the OSSE Attendance Tracking System to receive reimbursements. Subsidy providers also must participate in the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), which provides funding and training for nutritious meals for child care facilities, and this requires additional information be submitted through its own system. Similarly, if a provider participates in Head Start or Early Head Start, these programs have additional, separate federal reporting requirements and systems.

Navigating these systems takes time and expertise. Facilities that can afford to do so often hire an administrator whose sole job is to keep up with various application and reporting requirements and deadlines, including scheduling agency site visits for the multiple entities that require it. The costs to providers in staff time and resources can disincentivize their participation in the subsidy program.

The many systems and requirements also can increase reporting errors. Providers who need to correct an error are often unclear about where to get assistance. Survey results show that non-participating providers avoid the program because they have heard about the difficult process or have experienced it themselves. One provider in Ward 3 who is not participating in the subsidy program said, “the rules for participating would need to change, and I would likely need some administrative support to juggle all the new reporting requirements between the Pay Equity Fund, subsidy, and licensing.” Another center-based provider who just completed the subsidy application process warned, “if you are not business savvy or if you don’t do your own taxes, don’t expect to be able to fill out a subsidy form.”

OSSE should create a single portal where providers can submit all documents once and have visibility into how and when applications and documentation get processed. Many providers DCFPI spoke to who run facilities in multiple states brought up Maryland’s Child Care Provider Portal, operated by the Maryland State Department of Education, as a model for DC. Through this portal, Maryland providers can renew licensing applications, view and submit invoices, manage their attendance, upload documents, and view requests from families using subsidies seeking care. Not only does a single portal centralize regulatory requirements for providers, but it also increases transparency into the approval and renewal processes.

To Advance Racial Equity, OSSE Should Increase the Facilities that Can Determine Family Eligibility

Child care providers who participate in the subsidy program are categorized as either Level I or Level II providers. All licensed centers and homes are considered Level I for their first year of participation. Subsequently, child care centers can apply to become Level II providers, which allows them to determine subsidy eligibility directly with families at their facilities rather than have the families go through the application process with the DC Department of Human Services. This also enhances recruitment for the center because families can apply for both subsidy and a slot for their child in one visit.

Fourteen of the 26 Level II providers who responded to the survey said that becoming a Level II provider improved their enrollment process and increased the enrollment of children receiving subsidies, which increased enrollment overall.[20]

However, only child care centers are allowed to be Level II providers—home-based providers are not eligible to apply. A provider from the Spanish-language focus group mentioned that subsidies have provided long-term financial relief to families, especially those in need of bilingual education, and improved diversity and staff morale in the centers because subsidies allow members of their own communities to be taught in their classrooms. However, because home-based providers are excluded from becoming Level II providers, they miss out on these potential financial and community-building benefits.

Becoming a Level II provider requires assuming some level of financial risk, because a Level II provider is required to repay any payment errors that are a result of inaccurate eligibility determinations. This could pose a greater financial risk to home-based providers who often operate on tighter margins than center-based providers. As outlined above, being a Level II provider also requires additional training and technology, which can be costly. Not surprisingly, most Level II providers are larger centers that have the resources and staff to take on this additional responsibility.

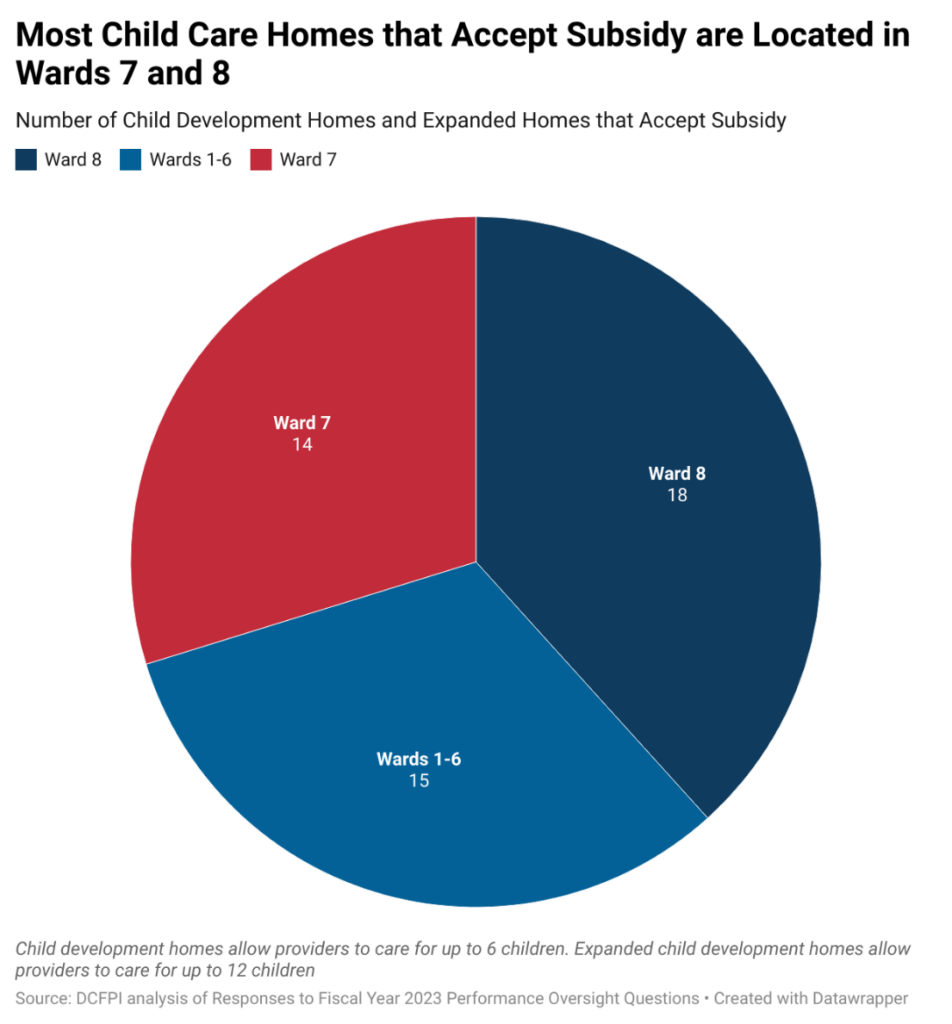

Although allowing home-based providers to be Level II providers may be complex, it is still worth pursuing. Wards 7 and 8 have more child development homes that accept subsidy than all other wards combined, according to OSSE oversight responses (Figure 3).[21] Extending Level II status to home care providers would have a positive impact where need for streamlined family eligibility determinations is the greatest. OSSE should consider offering start-up funding to home-based providers to help shoulder the cost of updating technology and compensating directors for their time as they complete the approval process and training. OSSE could also consider supporting a model of risk-pooling through an intermediary, a type of insurance that Level II providers can pay into so that funds are available when OSSE needs to recoup funding for a child deemed ineligible after a facility approves their eligibility and begins providing services.[22]

Level II providers are currently compensated for taking on subsidy eligibility determinations because they receive the full value of the subsidy plus the family co-pay directly from OSSE, as opposed to other providers, who receive the value of the subsidy but must rely on the families they serve to pay the co-pays. Some Level II providers still find the eligibility determination process challenging because the subsidy application for families is so complex. Simplifying the parent application process for child care subsidy would have the dual benefit of getting parents through the process more quickly and reducing the administrative burden for Level II providers. OSSE has made some efforts to simplify and streamline the parent application process, but more work needs to be done in this area.[23]

OSSE Should Improve Transparency and Communication with Child Care Providers

“Valuing and empowering schools as collaborating partners is key, as we are in direct contact with families and can help attract more participants to the program.”

Many providers expressed frustration over the lack of transparency regarding requirements for the program and delays in communication and approvals. In one focus group, a non-participating provider from a Ward 4 center highlighted the confusion surrounding participation criteria: “I would need to know more about how it would work and if it would fit with our program. We are play-based, Reggio-inspired, so I do not know if that would be ‘acceptable’ and if there are certain academic requirements we have to meet or a curriculum we would have to follow. If so, we wouldn’t want to participate.” This uncertainty about program expectations illustrates the need for more explicit guidelines and transparent communication to help providers navigate the process effectively.

Providers also often wait for long periods of time, sometimes weeks, after applying to the child care subsidy program to hear back from OSSE. At the same time, many directors stated the need for “help with the application,” and the need to receive “training about how to start participating in the program.” OSSE should offer more trainings on how to become a subsidy provider on the front end and provide more timely updates to providers who have applied. OSSE also should share more details on expectations, requirements, and reimbursement rates, particularly for facilities in areas like Wards 7 and 8 where families with low incomes face the largest child care gaps.[24]

Focus group participants were asked, “If OSSE could hire one additional support staff, what expertise should they have and what role should they play?” Overwhelmingly, they responded that OSSE would benefit from hiring someone with experience running a child care facility who can act as a coach to child care directors and can work across the various systems and agencies that affect child care in the District.

Directors also expressed the need for more bilingual support staff at OSSE to answer questions and guide Spanish-speaking directors through the process. OSSE should hire bilingual support staff to ensure that non-native English speakers are getting the guidance they need to serve their communities. Participants in the Spanish-speaking focus group noted that using external translators delays the process, causing more problems.

Additional Policy and Administrative Changes Needed to Build the Child Care System Families Deserve

The recommendations in this report will help more child care providers enter the child care subsidy program and offer affordable care to more District families, but they only address part of larger challenges facing the early childhood ecosystem. District policymakers will need to invest in the early childhood workforce and child care facility upgrades, and OSSE administrators will need to make process improvements for families and collect better data on the reach of the child care subsidy program to create a system in which every family who seeks child care can get it.

Workforce shortages continue to plague the early childhood education field and must be addressed by bolstering the salaries and benefits offered to early educators. Workforce shortages in child care are a direct result of low wages and inconsistent benefits, like health care and retirement.[25],[26] DC’s Pay Equity Fund helps to address workforce shortages by setting higher salary minimums for early educators in law, providing funding to child care centers and homes to meet these higher salaries, and offering a health care option through HealthCare4ChildCare. If lawmakers want to increase access to affordable child care, they will need to increase investments in both the child care subsidy program and the Pay Equity Fund to ensure that there is a sufficient workforce to meet the demand.

District policymakers should also invest in programs like Access to Quality that offer grants to expand child care facilities, support infrastructure updates, and increase the supply of child care slots, particularly in areas with the highest need. The Access to Quality program generated over 1,200 new infant and toddler seats when it launched in 2018.[27] With new funding, this program can help the District continue to increase the supply of child care to meet the demand.

OSSE can continue to improve access to the child care subsidy program for families by implementing presumptive eligibility. Presumptive eligibility allows parents to apply for a subsidy by providing baseline information on eligibility requirements, like proof of residency and income, and then receive a subsidy for their child while their full application is being reviewed and approved. Presumptive eligibility enables families to access subsidies faster and streamlines the application process.

Finally, OSSE should collect and report better data on the utilization of child care subsidies. OSSE currently reports utilization data for the subsidy program annually through the DC Council’s performance oversight process. They define and report utilization as subsidy enrollment as the share of total licensed capacity, which only tells us how many children using subsidy are in licensed classrooms compared to those on private pay. Advocates and administrators would benefit from having better data on the full scope of eligible families in the District to understand who is not accessing subsidy—including by age group and place—and why.

Acknowledgements

This report was developed with grant support from the Bainum Family Foundation and Children’s Equity Fund. DCFPI partnered with Travis Hardmon, President of Families First Early Education, Sally D’Italia, Director of the Children’s Center at Arnold & Porter, and LaDon Love, Executive Director of SPACEs in Action, to develop survey questions, lead outreach efforts to disseminate the survey, provide feedback on focus group questions, and recruit for focus group participants. BB Otero translated focus group questions and facilitated the focus group conducted in Spanish and was supported by Diego Molina, who took notes and translated them for analysis. The Under 3 DC Coalition provided funding to support the inclusion of a Spanish-language focus group. OSSE provided feedback on the survey, the initial recommendations, and the content of this report. DCFPI also extends its appreciation to the many child care directors and owners across the District who provided feedback through the survey and focus groups.

Appendix: Methodology

For this report, DCFPI developed and disseminated an online survey, available in both English and Spanish, to all 467 child care directors and owners in DC. We received a response rate of 17 percent, or total of 79 responses—71 responses to the survey in English and eight responses to the survey in Spanish. The survey varied in length depending on the attributes of the facility the respondent represented, but, on average, it took no more than ten minutes to complete the survey. All respondents received a $30 electronic gift card for completing the survey.

The survey was co-developed with three key community partners: Travis Hardmon, President of Families First Early Education, an organization that provides financial management coaching to child care providers, Sally D’Italia, Director of the Children’s Center at Arnold & Porter, a law firm located in Ward 6, and LaDon Love, Executive Director of SPACEs in Action, a local advocacy organization. Members of the Under 3 DC Coalition and OSSE also contributed to the development of the survey.

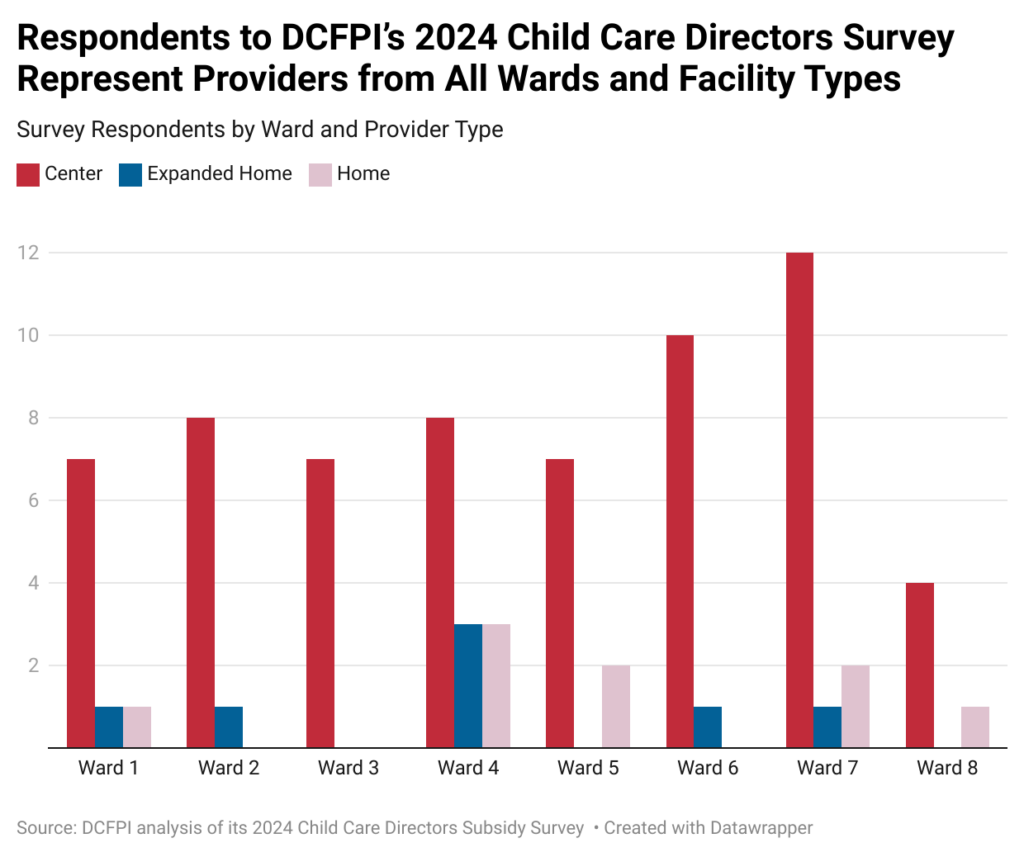

Among the 79 respondents to the survey, 80 percent represented child care centers and 20 percent represented child development homes and expanded homes. Respondents were also representative of all eight wards. Figure 4 below shows a breakdown of respondents by facility type and Ward.

To add context to the responses to the survey, DCFPI conducted three focus groups: one with current subsidy providers, one with providers not currently accepting subsidy, and one conducted in Spanish with a mix of subsidy and non-subsidy providers. Across these three focus groups, DCFPI had representation from:

- 13 subsidy providers and one non-subsidy provider;

- 11 directors representing child development centers and three owners representing child development homes or expanded homes; and,

- Directors and owners from Wards 1, 2, 4, 7, and 8.

The focus groups lasted an average of 90 minutes and participants received a $100 electronic gift card for their contributions. Participants were asked to give baseline information about the facilities they represent, such as whether their facility was a center or home, where their facility is located, whether or not they serve any special populations, such as children from homes where English is not the primary language spoken or children with special needs, whether or not they have a waitlist and/or empty seats, and what types of services parents on their waitlists are seeking.

After providing this baseline information, focus groups dug into what is working and not working with the various processes related to child care subsidy, including the application and approval process, reimbursements and reporting, and becoming a Level II provider. Focus group participants were also asked to reflect on the impact and benefits of providing subsidy seats in their facilities and specific steps OSSE could take to improve the experience of applying for subsidy and offering it in their facilities.

- Sarah Javaid and Melissa Boteach, “Child Care is Unaffordable in Every State,” National Women’s Law Center, February 2025.

- DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, “Responses to Fiscal Year 2023 Performance Oversight Questions,” February 2024.

- Annie D. Schoch, Cassie S. Gerson, Tamara Halle and Meg Bredeson, “Children’s Learning and Development Benefits from High-Quality Early Care and Education: A Summary of the Evidence,” Administration for Children and Families, November 2023.

- DC Action, “The Child Care Subsidy Program,” January 2021.

- Anne Gunderson, “Expanding Child Care Subsidies Would Boost the District’s Economy,’ DC Fiscal Policy Institute, July 2024.

- In 2023, there were 40,295 children in the District in families with incomes below 300 percent FPL, but only 7,699 children were served by child care subsidy, based on the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ analysis of American Community Survey data and utilization data from the DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education.

- Robyn Russell, Nkechi Enwerem, Zillah Jackson, “Child Care for Young Parents: A Missing Key to Intergenerational Upward Mobility in the District,” District of Columbia Primary Care Association, page 6, September 2023.

- DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, “Responses to Fiscal Year 2023 Performance Oversight Questions,” February 2024.

- Bainum Family Foundation, “Assessing Child Care Access: Measuring Supply, Demand, Quality, and Shortages in the District of Columbia,” January 2024.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Licensing Process for Child Care Providers, accessed October 2024.

- New America, “A State-by-State Look at English Learner Data,” accessed October 2024.

- Child care is a broken market, meaning that parents are paying as much as they can, but the amount they pay still does not meet the high cost of operating a child care center or home. Therefore, setting reimbursement rates based on a percentage of the current market rate for child care means that those accepting child care subsidy are forced to operate in the red and have to make up those losses elsewhere, like paying staff and educators less and asking parents to pay additional fees outside of tuition. New Mexico and DC used to be the only two states in the country to use a cost of care model to determine reimbursement rates until over 20 states indicated in their newest state Child Care Development Fund (CCDF) plans that they plan to use a cost of care model rather than the traditional market rate survey, according to a US Department of Health and Human Services administrator.

- DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, “Modeling the Cost of Child Care in the District of Columbia,” March 2023.

- Ibid.

- While reimbursement rates for some child development homes may exceed the cost of care, OSSE’s model assumes that operating costs, such as rent, utilities, and maintenance, are generally lower for homes compared to centers. This is because homes typically have fewer overhead expenses. While this difference is important, it requires closer examination to ensure that reimbursement rates accurately reflect the true costs faced by both home-based and center-based providers.

- DCFPI analysis of the 2024 update to the cost modeling study and the FY 2024 subsidy reimbursement rates.

- DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, “Modeling the Cost of Child Care in the District of Columbia,” slide 9, July 2024.

- Survey respondents were asked, “has becoming a Level II provider improved/expedited your enrollment processes,” and, “has becoming a Level II provider increased your enrollment of children receiving subsidies?” For both questions, 14 of the 26 respondents selected “yes.” Only 5 respondents to the first question selected “no” and 4 respondents to the second question selected “no.” All other respondents either said they were unsure or declined to answer.

- DCFPI analysis of OSSE “Responses to Fiscal Year 2023 Performance Oversight Questions,” Proportion of licensed childcare programs that participate in the subsidy program, by ward (broken down by facility type), page 98 and 99, February 2024.

- For more information on what a risk-pooling policy entails, see: Association of Governmental Risk Pools, “PR Toolkit for Public Entity Pools,” accessed October 2024.

- DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, “DC Child Care Subsidy Program Policy Manual: Summary and Overview,” October 2024.

- Bainum Family Foundation, “Assessing Child Care Access: Measuring Supply, Demand, Quality, and Shortages in the District of Columbia,” January 2024.

- Rose Khattar and Maureen Coffey, “The Child Care Sector Is Still Struggling To Hire Workers,” Center for American Progress, October 2023.

- Meg Caven, “Understanding Teacher Turnover in Early Childhood Education,” Institute of Education Sciences, June 2021.

- Under 3 DC, “FY26 Budget Letter to Mayor Bowser,” December 2024.