This report is supported by the Catalyst Grant Program through the Urban Institute and Microsoft Justice Reform Initiative, a collaboration to use data and technology to advance racial equity and reform in the adult criminal legal system.

Instead of a second chance at building a future, the millions of people across the US incarcerated and returning home from local jails and prisons each year often face ongoing punishment in the form of criminal legal fines and fees. In every state and DC, people who become involved with the criminal legal system must pay a host of fines, fees, and other financial obligations imposed at nearly every stage of the criminal legal process. These include cash bail, assessment fees or fines at the time of sentencing, and “pay-to-stay” fees for room and board, among others.[1] Revenues generated through these criminal legal fines and fees fund state and local government functions including court systems, police, services for victims of crime, and much more.

Historically, lawmakers throughout the US and DC used criminal legal fines and fees to criminalize and extract wealth primarily from Black communities, while forcing people to bear the cost of their incarceration for minimal or no wages at all.[2] These fines and fees have deep roots in a history of anti-Black racism, which is evident in the racial disparities within DC’s criminal legal systems today. While localities across the US impose different types of criminal legal fines and fees, they share common features. They 1) disproportionately harm Black people and people with low incomes; 2) often lead to perverse budgeting incentives; and 3) result in lasting harms for those unable to pay and their communities.[3]

Much of the impact of criminal legal fines and fees in DC is unknown because local agencies provide limited, and often outdated, public information about fines and fees and what they fund. To better understand the true costs of these financial penalties and identify policy solutions to address their harm, the DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI) conducted interviews with four formerly incarcerated DC residents in the fall of 2023 (Appendix 1). Those interviewed shared that:

- The federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), DC Department of Corrections (DOC), and the courts did not provide them or other incarcerated residents adequate information about the full range of financial obligations they would face or how the funds would be used.

- Fines, fees, and other financial obligations are difficult to afford, particularly fines and assessments imposed at sentencing and fees for everyday living expenses while incarcerated.

- Incarcerated individuals often cannot afford financial obligations and other criminal legal costs on their own without outside support and families and loved ones often have to help pay them.

- Inability to pay financial obligations and criminal legal costs resulted in harsh consequences that made day-to-day life incarcerated much more difficult. For example, those in DOC and BOP facilities who were unable to pay their financial obligations lost certain “privileges” such as phone use, accessing commissary items, and others.

Quotes from interviews with these formerly incarcerated residents are included throughout this report.

DC policymakers and public safety agencies should reform the District’s approach to criminal legal fines and fees. Doing so must include commitment to raising revenue in ways that are equitable and progressive, and moving away from criminal legal fines and fees that are regressive and disproportionately harm Black and low-income residents.

With input from formerly incarcerated DC residents, as well as lessons learned from other states that have undertaken criminal legal fines and fees reform, DCFPI’s recommendations for DC lawmakers include:

Improve Transparency of Fines and Fees

- Invest in the infrastructure and capacity of public safety data systems to collect, coordinate, and report on criminal fines and fees.

- Update and regularly publish general purpose non-tax and special-purpose revenue reports.

- Require the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Public Safety and Justice to publish a study of collateral consequences of criminal legal involvement and suggest recommendations for their reform.

Eliminate Fees that Exacerbate Racial Disparities and Economic Insecurity

- Eliminate DOC-imposed fees, including communication fees, commissary fees, work release fees, and any other fees imposed on residents in DOC custody.

- Prohibit incarceration for unpaid court fines.

Expand Supports for Those with Criminal Legal Involvement and Their Families

- Increase wages for residents incarcerated in DOC facilities.

- Expand tax credits to support people currently and formerly incarcerated.

- Pilot a guaranteed income program for people formerly incarcerated.

Table of Contents

I. Criminal Legal Fines and Fees are Rooted in a Deep History of Anti-Black Racism

Criminal Legal Fines and Fees Continue to Disproportionately Harm Black and Low-Income Communities

II. Fines and Fees Result in Lasting Harms for People Unable to Pay and Their Communities

The District Can Incarcerate People with Unpaid Criminal Legal Obligations

III. Fines and Fees Lead to Perverse Incentives

IV. Fines and Fees Are Imposed at Nearly Every Stage of DC’s Criminal Legal Process

Fines and Assessments Imposed at Sentencing

“Pay-to-Stay” Fees Imposed During Incarceration

Much Remains Unknown About the Full Impact of Criminal Legal Fines and Fees in DC

V. Recommendations to Mitigate the Harms of Criminal Legal Fines and Fees in DC

Improve Public Transparency of Fines and Fees

Eliminate Fees that Exacerbate Racial Disparities and Economic Insecurity

Expand Supports for People Involved in the Criminal Legal System and Their Families

Appendix 1: Interview Questions & Data Methodology Note

| Key Terms |

| Assessment:[4] A court-imposed fee on people involved with criminal legal system. An assessment is often imposed following a conviction, but the court can impose assessments even if a person is acquitted or their charges are dismissed.

Collateral Consequence:[5] The barriers returning citizens face to a successful reentry to their communities because of their criminal legal involvement, such as voting, employment, and housing restrictions. The harms of collateral consequences can last for decades, trapping people in cycles of poverty and hardship. Fee:[6] A monetary charge imposed by the government typically to cover costs of a service. Examples: Vehicle registration fees, licensing fees, ambulance fees. Fine:[7] A monetary charge imposed by the government to punish and deter undesirable or unwanted behaviors. Examples: traffic fines, fines for littering, panhandling fines. Probation:[8] A period of community-based supervision imposed by the court as an alternative to incarceration. Supervised Release:[9] A term of community-based supervision served after an individual is released from incarceration. Individuals are only eligible for supervised release after serving at least 85 percent of their sentence. |

I. Criminal Legal Fines and Fees are Rooted in a Deep History of Anti-Black Racism

Criminal legal system fines and fees are among the most harmful methods of government funding, particularly given the deep-rooted history of anti-Black racism in the US and its penal and legal institutions. Prior to the 13th Amendment, states and the District relied heavily on forced labor from enslaved Africans and their descendants. Law enforcement originated in many parts of the US mainly to protect the property and interests of wealthy, white men—which meant violently enforcing enslavement and the criminalization of Black people as the foundation of the economic system.[10]

As the nation edged closer to abolition and after, states continued to restrict the freedoms and extract wealth and labor from Black communities through Black Codes. DC enacted its first set of Black Codes in 1808, which fined “loose, idle, or disorderly Black persons” $5 if found on the street after 10pm.[11] In 1812, a more punitive set of Black Codes increased this fine to $20 and imprisonment for up to six months if unpaid.[12],[13] The 1812 codes authorized law enforcement to fine, incarcerate, or torture Black people in DC for begging or panhandling, attending church or a private meeting after 10pm, holding a dance without a license, riding horses, or keeping farm animals.[14] States largely ended Black Codes following Reconstruction, but through the ratification of the 13th amendment in 1865, the US abolished slavery while still authorizing states to force prisoners to perform unpaid labor.[15]

This loophole allowed states to continue extracting wealth and labor from Black people.[16] After abolition, in a system known as “convict leasing,” white-owned private businesses paid leasing fees to state, county, and local governments to contract prison labor.[17] Courts also placed people into the convict leasing system who were acquitted of crimes but could not afford their court fees, forcing them to work to pay off unpaid debt.[18] Across the US and particularly throughout the South, governments used revenues raised through convict leasing to fund courts, police, and other public services. In addition, imprisoned laborers built up much of the nation’s infrastructure—as enslaved Black people had before them. The practice of convict leasing lasted well into the mid-20th century.[19]

Through mass incarceration, the US prison population increased dramatically throughout the 20th century. And, due to ongoing forced labor and the imposition of fines for low-level offenses, state and local economies grew.[20] Between 1925 and 1981, the number of people incarcerated in state and federal institutions nearly tripled to 350,000 people.[21] Mass incarceration accelerated between 1973 and 2009, with the incarcerated population increasing by more than 700 percent.[22] Mass incarceration affected Black men in particular: for Black men born between 1945 and 1949, nearly 1 in 10 served time in prison by age 34. For Black men born in the 1970s, this rate increased to nearly 1 in 4.[23]

Between 1985 and 1987, as part of the national “War on Drugs” campaign, DC police arrested 25 percent of all 18- to 29-year-old men in the District on drug-related charges, nearly all of whom were Black. Despite making nearly 30,000 drug-related arrests and spending $6 million to increase enforcement during this period, DC’s police chief declared the campaign a failure in curbing drug use and improving public safety.[24] Ultimately, the campaign funneled tens of thousands of DC’s Black men through the criminal legal system and subjected them to predatory fines and fees.

Criminal Legal Fines and Fees Continue to Disproportionately Harm Black and Low-Income Communities

“A lot of people locked up come from families that don’t have a lot of resources already. So being incarcerated, they’re now putting even more financial burden on their families.” – Kevone N.

The generational harms to Black people and communities resulting from centuries of dehumanization, enslavement, segregation, criminalization, and incarceration persist today. The outcome of this violent history is evident in the racial disparities within DC’s criminal legal systems, which show that Black residents continue to bear the brunt of criminal legal financial obligations and the costs of incarceration. Despite accounting for less than half of DC’s population, Black people made up just over 82 percent of all arrests in 2023.[25] Black DC residents are also overrepresented in local jails and federal prisons. In 2023, Black Washingtonians accounted for nearly 90 percent of all individuals held in local DC jails and 95 percent of all DC residents incarcerated in BOP facilities.[26]

In a study of more than 9,000 cities, researchers found that those with larger populations of Black people collected more from court fines and fees per capita than cities with smaller Black populations. For example, cities included in the study collected, on average, $8 per person from court fines and fees while cities with the highest concentrations of Black residents collected as much as $20 per person.[27]

An unexpected fine or fee can have devastating financial consequences for people already struggling to make ends meet. Fines and fees are generally flat, meaning that the amount of a fine or fee does not increase or decrease relative to a person’s income. As a result, people with lower incomes spend a greater share of their earnings than people with higher incomes to pay for the same expense. The regressive nature of fines and fees also disproportionately harms Black communities who, on average, earn nearly 25 percent less per hour compared to white workers because of systemic racism.[28]

Considering the abysmally low wages paid to incarcerated workers, they often cannot afford criminal legal costs alone. People with low incomes comprise the majority of those incarcerated in the nation’s jails and prisons and workers in correctional facilities are paid well below minimum wage—if they earn wages for their work at all. For those that do receive pay for work performed while incarcerated, wages range between $0.13 and $0.52 per hour, on average.[29]

“You don’t stand a chance of surviving [incarceration] without family or someone sending you money.” – Dwayne T.

By imposing high costs while enforcing low wages for incarcerated workers, the criminal legal system pushes the burden of these financial penalties on the families and loved ones of those incarcerated and Black women in particular.[30] In a 2014 study of incarceration costs across 14 states, family members of those incarcerated were primarily responsible for criminal legal costs in 63 percent of cases.[31] Of the family members primarily responsible for these costs, nearly 85 percent were women—and since Black people comprise the majority of the incarcerated population, this burden falls most heavily on Black women.

The high costs to loved ones—particularly Black, brown, and low-income families—are incurred at nearly every stage of the criminal legal process. On average, families spent $13,607 on court-imposed costs for a loved one with criminal legal involvement in 2015 – roughly 71 percent of the poverty threshold for a single parent with two children.[32],[33] Moreover, this doesn’t include the additional costs families incur to support their loved one during incarceration. For example, families nationwide also spent an estimated $3 billion in fees for communicating with incarcerated loved ones over the phone and purchasing goods through commissaries in 2017.[34] Roughly two-thirds of families had trouble meeting their basic needs as a result of their relatives’ time incarcerated.[35]

II. Fines and Fees Result in Lasting Harms for People Unable to Pay and Their Communities

“You constantly have strain and pressure put on you after release… with a [criminal] background, you can’t get a lot of jobs or opportunities. I gave you all my debt, I gave you 31 years, what more do want from me? Let me show you why I deserve a second chance and how I can not only be a better citizen, but also make the community better.” – Darryl W.

Fines and fees in the criminal legal system are particularly exploitative because the US criminal legal system disproportionately incarcerates people in poverty and those experiencing homelessness. Compared to 5 percent of the US population who were unemployed in 2016, nearly 15 percent of people in state prisons were unemployed a month prior to their incarceration.[36] Additionally, people incarcerated in state prisons were nearly 25 times as likely to report experiencing homelessness prior to incarceration compared to the US average.[37] Incarcerated people are also more likely to have grown up in poverty and in single parent homes compared to people not incarcerated.[38]

In addition to disproportionately incarcerating people living in poverty, the criminal legal system continues to exploit people from disadvantaged backgrounds while in prison through criminal legal fines and fees. Such fines and fees contribute to a system of resource extraction from predominately Black and low-income communities.[39] While incarcerated, people are coerced to pay a number of financial obligations. If a person refuses to participate in a payment plan, they are subject to a series of punishments that make day-to-day living much more difficult. In federal BOP facilities, someone who does not make payments towards fines imposed during sentencing will lose certain “privileges” like more restricted commissary spending, denial of higher pay opportunities for work assignments, denial of drug treatment and community-based programs like halfway houses, placement in the least preferred sleeping arrangements, and more.[40]

Upon reentry, the consequences resulting from unpaid criminal legal fines and fees creates a cycle whereby those with inadequate income are saddled with large criminal legal debts that result in increased contact with the criminal legal system, reduced wealth-building and job opportunities, and a host of additional barriers to successful reintegration into their communities.[41] This debt compounds the already huge barriers formerly incarcerated people face to housing, public assistance, and more due to their criminal records and many are unable to pay these criminal legal fines and fees following release. In fact, workers who have been incarcerated earn only $0.53 for every dollar earned by the general population in the year of their release and just $0.84 for every dollar four years after.[42]

The pinnacle of this system of resource extraction is the ability of courts across the country to incarcerate people for unpaid criminal legal fines and fees. In 1983, the Supreme Court ruled in Bearden v. Georgia that courts could only incarcerate individuals who do not pay court-ordered fines and fees if they have the means to do so and willfully refuse to pay.[43] However, 40 years since Bearden, court systems continue to imprison people for being unable to pay court debts. Currently, nearly every state allows courts to incarcerate people for unpaid criminal legal fines and fees and in some jurisdictions—such as Huron County, Ohio—people who are unable to pay their debts make up more than 20 percent of the jail population at any given time.[44],[45]

People with unpaid criminal legal fines and fees also face other barriers to reentry. Currently, nearly half of all states either suspend, revoke, or prohibit renewals of driver’s licenses for individuals with unpaid fines and fees. (DC ended this practice in recent years.)[46] Additionally, many places prohibit those with unpaid debts from applying or renewing occupational or business licenses, garnish their wages, and restrict their voting rights, among other consequences.[47] Taken together, non-payment of criminal legal fines and fees often results in a “snowballing” of punishments that hinder formerly incarcerated people from successfully reintegrating into society.

The DOC and the BOP Garnish the Wages of Incarcerated People with Unpaid Criminal Legal Financial Obligations

Both local DOC facilities and the BOP garnish the wages of DC residents who have outstanding court-ordered debts, regardless of their ability to pay. Locally, the DOC garnishes half or more of the monthly wages earned by incarcerated DC residents.[48] Under the Inmate Financial Obligations Program, each month people in DOC facilities who owe at least $5 in court-ordered costs, such as assessment fees, must do whichever costs less: 1) put half of their monthly wages toward their debt balance or 2) pay off half of their remaining balance.[49] In BOP facilities, people participating in the “highest paying” work assignments, which provide extremely low-cost labor to private companies, are required to pay at least 50 percent of all earned wages toward their unpaid court debts.[50] People in lower-paying work assignments are required to pay at least $25 toward their debts each quarter.[51] As a condition of release, the DOC and BOP require anyone with outstanding financial obligations to pay their debt in full, and failure to do so can result in reincarceration.[52],[53],[54]

The District Can Incarcerate People with Unpaid Criminal Legal Obligations

DC residents can be incarcerated for up to a year for unpaid court financial obligations.[55] While the DOC does not report how frequently DC residents are incarcerated for failure to pay court-ordered debts only, there is some visibility of these cases at the federal level through the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA). Similar to DC’s prison system, the federal government also has oversight over DC residents following their release through probation, supervised release, and other forms of community supervision.[56]

While CSOSA does not report the number of those incarcerated just for failure to pay, these cases are reported and classified by CSOSA as a “violation of release,” which also include things such as failing to report for parole hearings, failing court-ordered drug screenings, and others.[57] As of 2022, 23 percent of DC offenders under community supervision were arrested for these technical violations. And while these cases declined significantly during the pandemic, they are trending back toward pre-pandemic levels. Police arrested around 2,500 people in DC for technical violations in 2019. That number dropped to fewer than 1,400 in 2021 but ticked upward to more than 1,600 people in 2022—a 15 percent increase.[58]

III. Fines and Fees Lead to Perverse Incentives

Typically, fines and fees are not a large share of state and local government revenues. Nationwide, fines, fees, and forfeitures account for less than 1 percent, on average, of local revenues.[59],[60] However, in DC, revenue from criminal legal and civil fines, fees, and forfeitures are projected to account for at least 4 percent of local revenues in fiscal year 2025.[61] In the year prior to COVID, these revenue sources only accounted for just over 3 percent of local revenues, but with Mayor Bowser’s addition of 342 additional traffic cameras in 2023, revenues from traffic fines are expected to double between fiscal years 2024 and 2025.[62],[63]

States and localities have often increasingly turned to fines and fees to fill budgetary gaps. For example, in response to declining federal funding during the 1980s, state and local governments increased the number of fines and fees imposed on people for traffic, misdemeanor, and felony offenses to generate increased revenue.[64] Similarly, many states and localities deepened their reliance on these regressive revenue sources following the 2008 Great Recession.[65]

Using regressive fines and fees to fund core government services can jeopardize those services if fewer people are penalized or if fines and fees are reduced or eliminated. As a result, jurisdictions have a perverse incentive not only to maintain current fine and fee revenues but also to increase these revenues over time through issuing additional or harsher fines and fees.

The most infamous example of this was uncovered in the 2015 Department of Justice (DOJ) investigation into the Ferguson Police Department (FPD).[66] To maintain the city’s services, elected officials in Ferguson urged FPD to dramatically increase policing and enforcement to generate more revenue through court-imposed fines and fees. Not only did FPD provide performance incentives for officers as they made more arrests and stops, but the courts also created new fees for having arrest warrants cleared, failing to appear in court, and fees for repeat offenders.

The revenue generating incentives of FPD were so predatory they often undermined purported public safety goals. According to the DOJ’s investigation, “Ferguson’s law enforcement practices are shaped by the City’s focus on revenue rather than by public safety needs. This emphasis on revenue compromised the institutional character of Ferguson’s police department, contributing to a pattern of unconstitutional policing, and also shaped its municipal court, leading to procedures that raise due process concerns and inflict unnecessary harm on members of the Ferguson community.”[67]

IV. Fines and Fees Are Imposed at Nearly Every Stage of DC’s Criminal Legal Process

Because Congress continues to deny DC statehood, much of the District’s criminal legal system is under federal authority. DC’s unique criminal legal system makes it difficult to understand the full scope of fines and fees and conceals the full scale of the harm to residents. And, people who are involved in DC’s criminal legal system cycle between local and federal agencies, which often have different fines and fees policies.

For example, people convicted of felony offenses and sentenced to more than one year are housed in federal BOP facilities in states across the country. Alternatively, DC residents convicted of misdemeanor offenses that carry a sentence of one year or less, those awaiting trial, and those awaiting transfer to BOP facilities are housed in local DOC facilities.[68]

As discussed below, DC residents must pay a variety of fees while incarcerated, and these fees can vary depending on where they’re housed. For example, a phone call costs typically less at the local Central Detention Facility (CDF) than at BOP facilities.[69] Additionally, while BOP facilities charge co-pays for medical services, local DOC facilities do not.[70],[71]

Although the criminal legal fines and fees landscape in the District is not fully transparent, people involved in the criminal legal system may have to pay a number of financial penalties, including criminal assessments and fines, communication fees, commissary fees, and work release fees. Individually, these costs are incredibly burdensome; cumulatively, these penalties can be devastating for people with criminal legal involvement and their loved ones—especially if they cannot afford to pay.

Fines and Assessments Imposed at Sentencing

“My punishment should be my sentence.” – Gene D.

The Courts Impose Fines for Anyone Convicted of a Criminal Offense

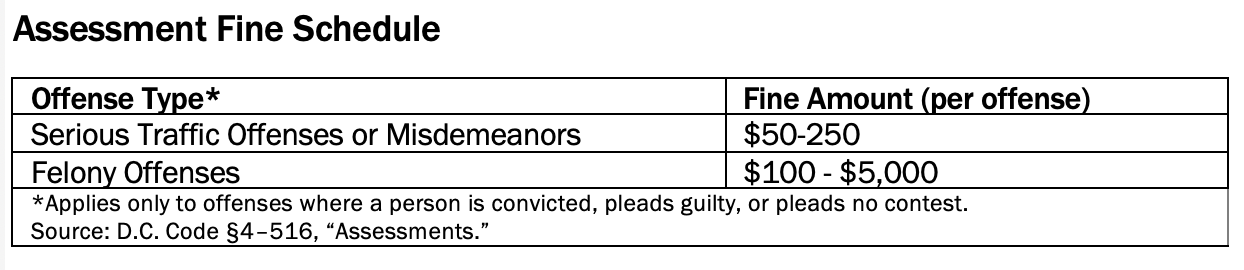

People convicted of a DC code violation must pay court-imposed assessments for each violation or offense. The court automatically imposes assessment fines, and their cost depends on the severity of the offense (Table 1).

Revenues from assessments partially fund two separate support programs for victims of crimes. First, these revenues are deposited into the Crime Victims Compensation Program (CVCP), administered by the DC Superior Court, which is used to directly compensate victims of crime.[72],[73] Half of CVCP funding is then deposited into the Crime Victims Assistance Fund which is used for outreach purposes to increase the number of crime victims who apply for direct compensation.[74]

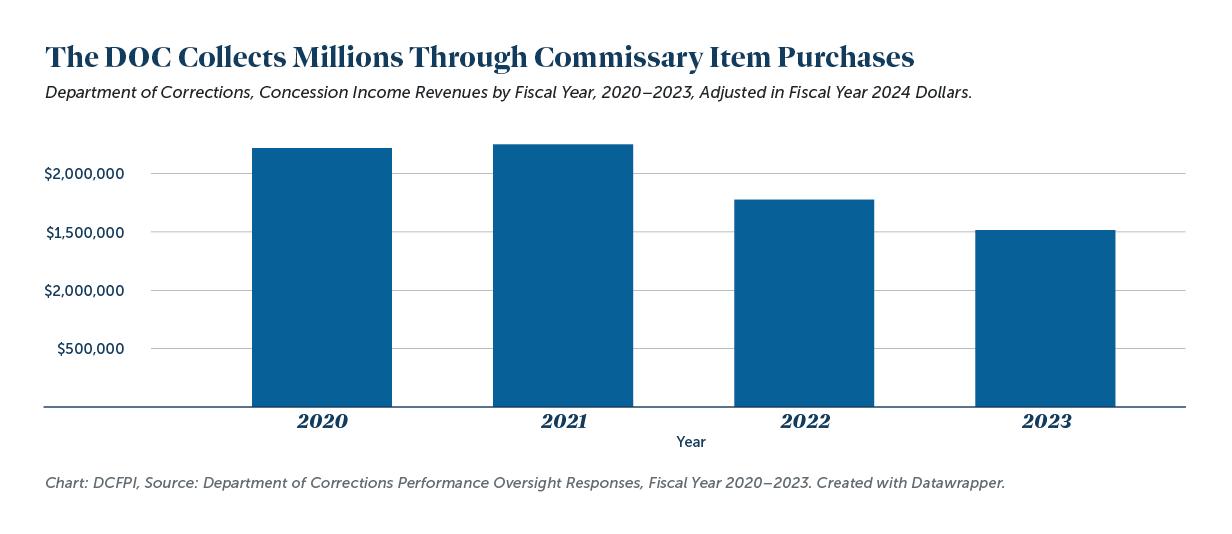

In addition to required court assessment fees, judges can impose criminal fines on people convicted of DC Code violations. Criminal fines can cost much more than court assessments, ranging from $100 for minor offenses up to $125,000 for offenses punishable by 30 years or more (Table 2). Funding from criminal fines can be used for general purpose revenue.

“Pay-to-Stay” Fees Imposed During Incarceration

“The cost of living in prison is high—meaning you have to pay for basically everything. The things they give you for free aren’t always worth having.” – Gene D.

High Phone Call Fees Are a Barrier to Maintaining Contact with Loved Ones

People must also pay fees to cover the costs of their own incarceration. One of the primary ways people who are incarcerated stay connected to family and friends is by phone. The individuals DCFPI interviewed for this report consistently reported that they experienced high costs while incarcerated in local and federal facilities, particularly for telecommunication services to maintain contact with their loved ones.

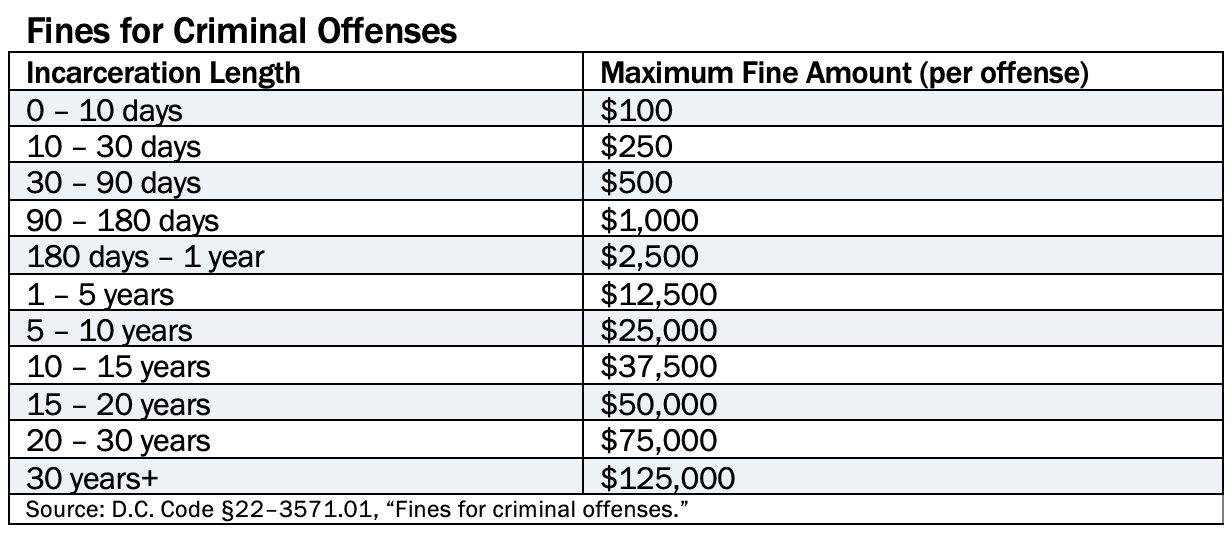

In local and federal facilities, phone calls are restricted to 15 minutes and the per-minute fee for phone calls at DOC facilities is $.08.[75],[76] Workers in local DOC facilities earn either $3 or $4 per day, which translates to a maximum wage of $.50 per hour.[77] Even at the maximum wage, the price of a single phone call is more than double the hourly earnings for someone incarcerated in local DOC facilities (Figure 1).

Currently, the DOC’s phone rates are higher than rates at many other jails throughout the country. The Baltimore City Correctional Center, for example, only charges $0.05 per minute for phone use, while other facilities in Texas, California, and West Virginia charge between $0.01 and $0.03 per minute.[78] Several states have eliminated fees and surcharges for phone calls in state jail and prison facilities, most recently Massachusetts in 2023.[79]

In BOP facilities, phone rates are even higher. Because DC residents housed in BOP facilities are often hundreds of miles away from home, they pay a premium for interstate calls. Instead of paying $0.08 per minute for in-state calls, people in BOP facilities must pay rates capped at $0.14 per minute for out-of-state calls.[80] Wages paid to incarcerated workers in federal facilities range, on average, from $0.12 cents to $0.40 cents per hour.[81] At a phone fee rate of $.14 per minute, a single 15-minute phone call would be more than five times the maximum hourly wage of incarcerated workers in federal BOP facilities.

Because of the high costs of phone calls, relatives and loved ones of people who are incarcerated often incur phone fees to stay in contact. This is especially true for DC residents in BOP custody, who are often far from home. Although the law requires that DC residents be incarcerated within 500 miles of the District, nearly 25 percent of DC residents are held in facilities more than 500 miles away.[82] This distance makes it extremely difficult, if not impossible, for loved ones to visit their incarcerated family members or friends.

Commissary Costs Can Prevent Incarcerated People from Accessing Goods to Meet Their Basic Needs

“To be incarcerated and have to pay those prices for commissary is wrong. And it shows clearly that the system is profiting off the inmates.”- Darryl W.

Many residents incarcerated in DC jails must purchase commissary items to meet their basic needs.[83] In a survey of people incarcerated in DOC facilities, over 70 percent responded that they were served spoiled or rotten food.[84] Because of the unsafe and inhumane food options provided by the DOC, people often rely on food purchased through commissary for their meals. They also rely on the commissary to purchase products for their health and hygiene, such as soap, toothpaste, and deodorant, in addition to things like stamps and paper to maintain communication with their loved ones.

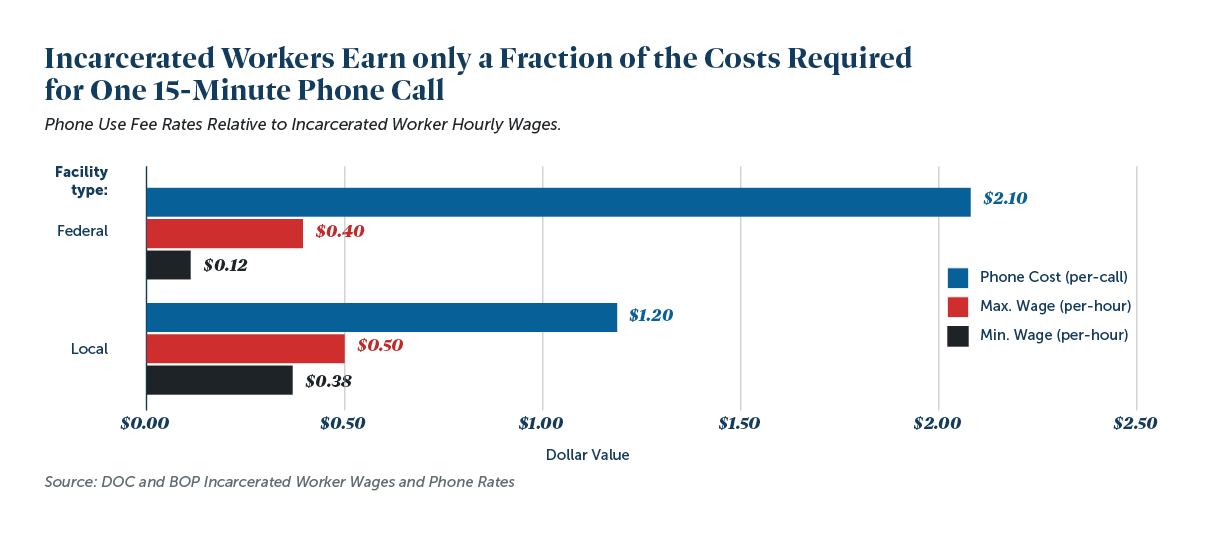

For people without monetary support, commissary prices can be extremely unaffordable, especially given the exploitative wages incarcerated workers earn. For example, a bundle of goods consisting of tuna ($2.51), toothpaste ($3.71), and a t-shirt ($5.24) would cost $11.46. Based on the prevailing wage for DOC workers, this would take 84 working hours to afford, without outside financial support. Additionally, the DOC charges a 6 percent surcharge on all commissary goods, and periodically increases commissary prices to keep up with inflation. In January 2024, the DOC increased all commissary prices by 3.5 percent.[85],[86] Between 2018 and 2023, the DOC generated just over $2 million per year from items residents purchased through the commissary, on average (Figure 2).[87] The DOC uses this money to re-stock the commissary, and funding cannot be used to fund other District programs and services.

While commissary food items are vital for many incarcerated residents in DOC facilities, they shouldn’t take the place of the daily meals provided through DOC. Recently, DC has considered legislation to improve food safety, quality, and more in DOC facilities with the FRESH STARTS Act of 2023.[88] Although some parts of this bill were included in the adopted version of the Secure DC law—such as the requirement for all meals provided by DOC to meet federal nutrition and dietary guidelines—many components of FRESH STARTS were not included. For example, the FRESH STARTS Act proposed funding for those without financial support to purchase commissary food items, referred to as the Fresh Foods Fund. Establishing a fund for commissary items is critically needed given their high costs and as the DOC works to improve food conditions.

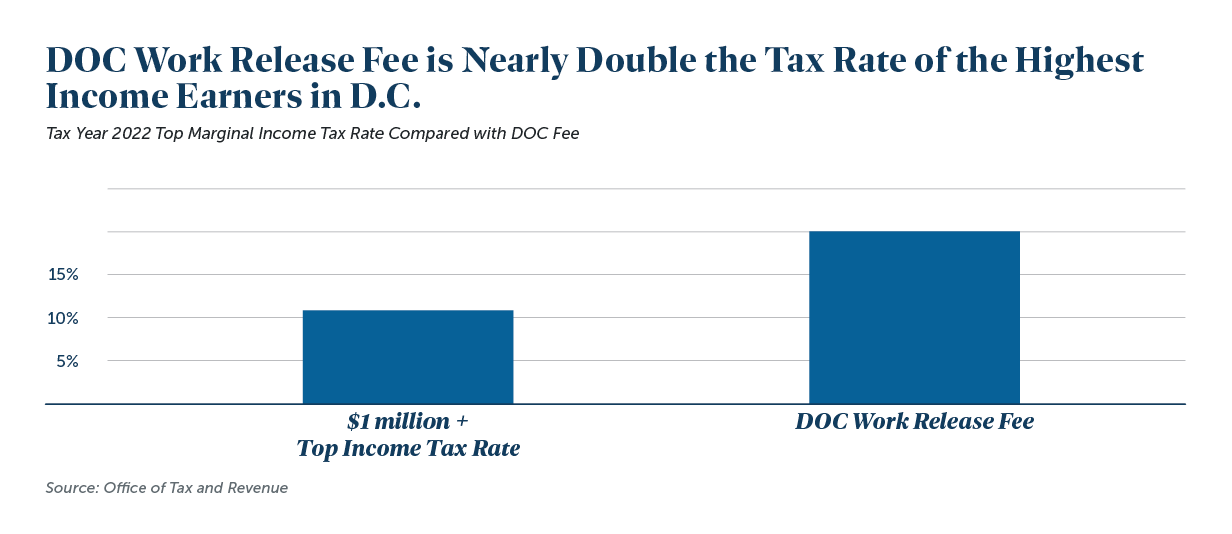

Work Release Program Fees Are Effectively a Twenty Percent Income Tax on Incarcerated Workers’ Wages

The DOC also requires incarcerated workers to pay “fees” on any wages they earn through the DOC’s work release program, which allows eligible residents in DOC facilities to work jobs outside of jail facilities.[89] Typically, participation in the work release program is reserved for DC residents sentenced with misdemeanors, those nearing the end of their jail or prison sentence, and those incarcerated for nonpayment of court ordered fines, among other circumstances.[90] Currently, the DOC can impose a 20 percent fee on any wages above $50 earned by people participating in the work release program, with the fees going to pay for workers’ room and board.[91] Fees for work release aren’t unique to DC. Baltimore charges incarcerated workers a flat fee of $60 per week, and Anne Arundel County, MD, charges them $15 for each day worked. [92],[93]

Although classified as a fee, the 20 percent surcharge on workers’ wages functions as an income tax—one imposed at a rate nearly double the rate of DC’s highest earners (Figure 3).[94] Between 2010 and 2018, DC generated more than $16,000 annually from work release fees, all of which the District deposited into its general operating budget.[95],[96] Notably, DOC paused enforcement of this fee following COVID-19 and it has not resumed.[97] However, the agency is still authorized to impose this fee under DC Code and DOC official policy and may resume enforcement at any time, as other states have done. In Wisconsin for example, jail and prison facilities have already reinstated fees that were on pause during COVID-19.[98]

Much Remains Unknown About the Full Impact of Criminal Legal Fines and Fees in DC

“A lot of people in the broader community don’t know about these costs…we’re receiving double, triple, sometimes quadruple levels of punishment.” – Darryl W.

In addition to most of DC’s criminal legal system being under federal authority, local agencies only provide limited, and often outdated, public information about fines and fees revenues and what they fund. For example, while the Office of the Chief Financial Officer (OCFO) publishes revenues collected from various fines and fees, these revenue sources were last described in detail in 2015.[99],[100] Additionally, DC courts do not publish comprehensive data related to court costs, how many people are unable to pay, or the consequences of non-payment.

Between July and December 2023, DCPFI conducted direct outreach to a range of DC agencies, but many were unresponsive or unable to provide certain data outside of formal information requests. Not only can information requests take months or longer for agencies to fulfill, not all agencies must respond to information requests. For example, the local Public Defender Service is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), because it is an independent, non-government agency. The federal Public Defender Service also is not subject to FOIA, because it is an agency of the federal courts. So, while courts can waive public defense fees in DC for defendants with very low incomes, neither the federal nor local Public Defender Service detail how often this happens, and they are not required by law to provide this information when requested. Parole and probation services also fall within the jurisdiction of the federal courts and, as such, are not subject to FOIA requests.[101] Despite these data challenges, as of May 2024, DCFPI has submitted information requests to various government agencies, including the DOC and BOP.

V. Recommendations to Mitigate the Harms of Criminal Legal Fines and Fees in DC

The criminal legal system can hold people accountable to existing laws and public safety goals while also recognizing that historical, social, and economic context—such as the experience of poverty, trauma, and economic hardship—plays a role in causing crime.[102] Broadly, the District should work to reduce reliance on regressive revenues and untether fines and fees from the provision of core government functions. DC should look to replace revenues from criminal legal fines and fees with equitable funding sources.[103]

As a result of federal oversight, local lawmakers do not have full control over changes to DC’s criminal legal policies and procedures. First, any changes to the DC criminal code ultimately require congressional approval. Congress blocked changes to DC’s criminal code in 2023, and federal authorities could continue to hamstring local reform efforts.[104] Second, DC residents with felony offenses are incarcerated in federal prisons across the country where they’re subject to fees imposed by the BOP which often vary by facility.

Although DC’s criminal legal system is unique in these ways, lawmakers can and should take steps to mitigate the harms of criminal legal fines and fees for Black and low-income communities. In advancing reforms, District lawmakers should follow three core principles: 1) improve public transparency of fines and fees; 2) eliminate fees that exacerbate racial disparities and economic insecurity; and 3) expand supports for people with criminal legal involvement and their families.

Improve Public Transparency of Fines and Fees

The District’s lack of publicly available and up-to-date reporting on criminal legal fines and fees prevents the public from understanding the full extent of their reach and harm. Largely due to federal oversight, public reporting of criminal fines and fees collection is disjointed, with various agencies responsible for collecting, enforcing, and publishing information specific to these revenues. Additionally, current fines and fees reporting does not include metrics that detail how criminal fines and fees impact specific populations of DC residents, including defendants who cannot afford to pay, residents of color, and residents with disabilities, among others.

Greater transparency around the collection, costs, and impact of criminal fines and fees—particularly for historically marginalized communities—can help researchers, advocates, and policymakers recommend and implement tailored supports for returning citizens, hold District lawmakers accountable to reforms, and inform future investments by the DC Council to support people impacted by the criminal legal system.

Invest in the infrastructure and capacity for public safety data systems to collect, coordinate, and report on criminal fines and fees. Various local and federal agencies are responsible for imposing and collecting criminal legal fines and fees, and no public agency is tasked with serving as a clearinghouse for these data. Currently, agencies have different data collection requirements, uncoordinated data management systems, and no shared public reporting requirements—leaving the District’s criminal legal fines and fees data difficult to access and piecemeal at best.

Bolstering relevant agencies’ data collection and reporting capacities, as well as increasing interagency coordination, are critical to increasing data transparency. To support these efforts, lawmakers could conduct a systemic review of agencies’ existing data collection practices and data sharing agreements to better understand what information is already collected, where and how those data are shared, and where data sharing connections across agencies can be improved. Where gaps exist in data collection and sharing, lawmakers could work with agencies to identify common reporting metrics or to create data sharing agreements.

The District could also create a commission focused on improving criminal legal fines and fees reporting. Agencies on the commission could include the Deputy Mayor for Public Safety and Justice (DMPSJ), Corrections Information Council, and Criminal Justice Coordinating Council. The commission could also include formerly incarcerated people, their families, and community members most directly harmed by extractive criminal legal costs and compensate these participants for their time. District leaders could require that commissioners work together to provide comprehensive reporting on criminal legal fines and fees, including the total dollar amount of criminal fines and fees collected from DC residents, how often defendants default on court-ordered payments, and a demographic breakdown of characteristics of residents who are impacted, like race and ethnicity, income, and gender. The commission could model its approach to reporting after the state of Virginia, which has issued comprehensive reports about criminal legal fines and fees since 2002.[105]

Update and regularly publish general purpose non-tax and special-purpose revenue reports. The OCFO annually publishes revenues collected from tax, non-tax, and other revenue sources used to fund District programs and services. Within these revenue chapters, fines and fees are reported as non-tax revenues separated into two main categories: 1) revenues that can fund any District service (general purpose) and 2) revenues that are earmarked for specific programs and services (special purpose).[106] However, despite the OCFO reporting revenues for hundreds of general purpose and special purpose revenue sources generated from fines and fees, it does not provide detailed information, such as their rate structure, purpose, if funds are used immediately or accrue interest, and other details.

Previously, the OCFO published supplemental general purpose and special purpose revenue reports that provided this kind of detailed information.[107],[108] However, the OCFO has not released these reports since 2015, despite numerous additions and revisions to existing fines and fees. For example, in 2015, the OCFO reported 99 unique general purpose non-tax revenue sources generated from fines and fees.[109] By 2019, this number increased to 153—an increase of 55 percent.[110],[111] Given that these supplemental non-tax revenue reports provide the most extensive fine and fee revenue data, the OCFO should update them every two years.

Require the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Public Safety and Justice to publish a study of collateral consequences of criminal legal involvement. In 2020, the Council passed the Removing Barriers to Occupational Licensing for Returning Citizens Amendment Act. [112] This legislation required DMPSJ to complete a study of the collateral consequences of criminal records specific to occupational and business licensing. The law required DMPSJ to submit this study to the mayor and DC Council by January 1, 2022, but did not require the mayor or DC Council to publish the study or to consider its findings in future legislation. In fact, DMPSJ did not complete the study at all.[113]

The Council should work with DMPSJ to understand why the study was not completed, find solutions for completing it in a timely manner, and then direct DMPSJ to make the results publicly available. Additionally, any study of collateral consequences should include barriers associated with non-payment of court-ordered fines and fees, given that imposed penalties include wage garnishment and re-incarceration. The study should also provide actionable recommendations that District lawmakers can take to minimize and reduce identified barriers associated with having a criminal record.

Eliminate Fees that Exacerbate Racial Disparities and Economic Insecurity

Given that the District does not have authority over criminal legal fines and fees impacting DC residents in federal facilities, DC policymakers should first work towards eliminating criminal legal costs imposed locally. District lawmakers should take intentional aim to repair the harms of the well-documented and extensive history of wealth extraction from Black communities through jails, prisons, and courts.

Longer-term efforts will be needed to reduce the harms of criminal legal fines and fees in federal facilities. Reducing the costs of maintaining contact with relatives, affording basic goods through commissaries, and reentering society without debt is especially needed among DC residents serving time for felony offenses in federal BOP facilities, given their distance from home and the extra costs this poses to them and their families.

Eliminate DOC fees, including:

Communication Fees. Ensuring people can maintain contact with loved ones while incarcerated is essential to their well-being and benefits society, research shows.[114] Consistent communication with family and friends reduces anxiety and depression among incarcerated individuals while also improving relationships, especially among parents and their children. Moreover, maintaining close contact with loved ones has been linked to reduced rates of reincarceration, particularly for incarcerated women.[115]

DOC can implement free phone calls in several different ways. For one, the DOC could establish daily or weekly limits on the number of free calls allowed by residents housed in local facilities to manage call volumes. Alternatively, the DOC could also use the existing call making capabilities of the tablets issued to those housed in DOC, similar to the approach of Massachusetts. Although implementing free phone calls will require greater coordination and input, particularly from currently and formerly incarcerated residents, DC should join other states in eliminating fees for phone use in local jails. Additionally, DC should work to eliminate other costs associated with maintaining contact with loved ones including fees for mail, email, video calls, and others.[116]

Commissary Fees and Surcharges. With so many DC residents incarcerated in DOC facilities relying on commissary goods for their nutrition, hygiene, and other basic needs, DC should take two steps to improve conditions and reduce the burden of fees. First, it should ensure vast improvements in the quality of the food already provided to people in DOC custody. Policymakers could start by establishing the Fresh Foods Fund while also still working to improve food quality and nutrition provided by DOC. Such a fund should be expanded to include all other commissary items, like hygiene products, given that people in DOC facilities also rely on commissary for non-food items.

Second, DC can eliminate commissary fees and surcharges as has been done in other localities, such as Philadelphia, which eliminated commissary surcharges in 2021.[117] Eliminating the 6 percent commissary surcharge in DC would cost just under $120,000 per year.[118] Eliminating all commissary fees would require the District to raise around $2 million in additional revenue per year.

Work Release Fees. Fees for room and board charged to people earning wages under DOC custody are not unique to DC. On top of the other costs of incarceration detailed throughout this report, work release fees push the responsibility of financing jail and prison operations from all taxpayers to people who are in custody. Although the DOC paused enforcement of work release fees at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, DC Code and DOC policy still authorize these fees. Given these fees could be reinstated and harm DC’s incarcerated residents, lawmakers should permanently eliminate them.

Prohibit incarceration for unpaid court-ordered fines. Imposing hefty fines and fees for criminal offenses, and then incarcerating those who cannot afford to pay, is the epitome of modern-day debtor’s prisons—which were formally abolished nearly two centuries ago. The court does allow defendants who cannot afford to pay to forgo payment of fines and fees at the time of sentencing; however, the court requires these defendants to pay costs in full after sentencing, even if they still have no means to pay.[119] People with criminal records face barriers to securing employment, business and occupational licenses, and other supports, which makes incarceration for unpaid fines predatory and counterproductive to actually collecting these fines. Other localities, such as Fairfax County, VA, have allowed people who are in default of court-ordered costs to complete community service in lieu of payment or incarceration.[120] DC lawmakers should abolish the possibility of incarceration for unpaid criminal fines and fees from DC Code and coordinate with the DOC and other District agencies to provide alternatives to incarceration for non-payment of court fines.

Expand Supports for People Involved in the Criminal Legal System and Their Families

“Instead of educating [incarcerated people] about how our finances are or are not used, they’ll just try to take advantage of us financially only to then have us come home where we can’t find housing, jobs, and other opportunities. It’s really disheartening.” – Gene D.

Holistic solutions are needed to address the harms of criminal legal system involvement, including the associated fines and fees and the negative impact on people’s economic security, housing stability, and overall well-being. DC does take steps to support people returning home from incarceration. For example, Project Empowerment is a transitional jobs program that offers paid work, training, education, and supports for people facing barriers to employment, including criminal legal system involvement, to help them connect to the workforce.[121] Additionally, the Mayor’s Office of Returning Citizens Affairs provides a limited number of housing vouchers for DC residents returning home.[122]

While these and other supports are valuable, the District can and should do more to bolster economic and financial security for those with criminal legal involvement and their families. By increasing economic supports, DC can assist people with criminal legal involvement in their reentry and their families in affording the costs of incarceration – promoting greater healing and rehabilitation instead of intensifying punishment.

To eliminate criminal legal fees and expand supports for those with criminal legal involvement would require the District to invest greater resources towards incarcerated residents and their families. DCFPI has recently published proposals policymakers could consider to increase revenue, which include adopting a higher marginal property tax rate for single family homes with taxable values over $1.5 million, increasing the capital gains tax rate, and more.[123] These proposals are not only more equitable than fees imposed during incarceration but they also have broad support among District residents.[124]

Increase wages for residents incarcerated in DOC facilities. Everyone, regardless of whether they are incarcerated, deserves to be compensated fairly for their work. Wages for incarcerated workers in local and federal facilities are deeply exploitative and force many people to rely on financial support from family members and loved ones to afford everyday living costs while incarcerated.

Due to federal oversight, DC does not have authority over wages that DC residents earn while incarcerated in federal facilities. However, DC can and should reform wages for residents incarcerated locally by requiring all work assignments in DOC facilities to meet federal minimum wage standards. DC could work to model local legislation after the congressional Fair Wages for Incarcerated Workers Act introduced in 2023.[125]

Expand tax credits to support people currently and their families. Currently, DC has one of the most generous and inclusive Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC) in the nation. In addition to matching 100 percent of the federal EITC starting in tax year 2026, the DC EITC also extends to undocumented workers, or filers using Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers—two design features that are uncommon in most states.[126] However, both the federal and local tax credits explicitly exclude the income of incarcerated workers.

While DC lawmakers lack authority over federal tax credits, they should expand the local definition of earned income to include wages earned while incarcerated for the DC EITC. This might mean allowing the earnings of the incarcerated worker to count toward their family’s income when claiming the EITC for families. Or it could mean allowing the incarcerated workers in local or federal confinement to retroactively claim the EITC upon reentry based on the earnings for the years during which they were incarcerated or using earnings from a year prior to incarceration. Doing so would aid in successful reentry and reduced recidivism through greater economic security for those incarcerated and their families.

Pilot a guaranteed income program for formerly incarcerated people. To help support residents’ reentry and test the ability of income to reduce recidivism, DC should pilot a guaranteed income program for people immediately following their release. Recent cash transfer programs for returning citizens have shown promising results and can serve as the basis for DC’s approach. For example, from April 2020 to March 2021, the nonprofit Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO) enrolled more than 10,000 returning citizens in its Returning Citizens Stimulus (RCS) Program, the largest ever cash transfer program for formerly incarcerated individuals.[127] The program provided up to $2,750 to formerly incarcerated people across 28 cities.[128] RCS participants said that the payments “provided tremendous financial relief in the period immediately following their release,” helping them get back on their feet and afford everyday expenses.[129] Compared to CEO participants who did not receive the cash transfer, those who did were also more likely maintain employment one year after being placed into a job.[130]

Between November 2021 and April 2023, Chicago-based nonprofit Equity and Transformation ran a guaranteed income pilot that provided an unconditional $500 per month to 30 formerly incarcerated people with low incomes.[131] Pilot participants reported being able to better cover housing, food, child care, and other everyday living costs.[132] A guaranteed income program for DC residents coming home from incarceration can make the reentry process smoother and promote successful outcomes.

Appendix 1: Interview Questions & Data Methodology Note

For this report, DCFPI conducted interviews with four formerly incarcerated DC residents during the fall of 2023. Interviews provide insights into what people think and offer a deeper understanding of the lived experiences of people directly impacted by the issue or policies at hand. DCFPI’s interviews aimed to gain firsthand information from individuals from DC who were formerly incarcerated in DOC and various BOP facilities.

Each interview lasted approximately one hour, and all participants received gift cards for their participation. The conversations from these interviews greatly helped to inform this report. While conversations in each interview varied, the general questions that DCFPI asked in each interview included:

- Can you describe any fines or fees you were ordered to pay? For example, were you responsible for any of the following costs:

- Fees for telephone use?

- Fees for medical care?

- Fees on any wages earned while incarcerated or under supervised release?

- Other costs?

- How long did the courts give you to pay these fines or fees? Was this enough time?

- Were you able to afford court ordered fees? If not, what were the consequences of not paying?

- Were you ever able to have a fine or fee waived? If so, what was the process like?

- How did having to pay these fines and fees affect your well-being? Put another way – what was the impact of these fines and fees on your life?

- At any point, did you know how the system used the fines and fees you were required to pay? Put another way, do you know what these fines and fees funded?

- Have you ever asked relatives, friends, or other people close to you to help pay your fines and fees? If so, how did that affect their finances and well-being?

- If you could change anything about the fines and fees system, what would it be? What do you want elected officials to know about fines and fees?

[1] Anne Teigen, “Assessing Fines and Fees in the Criminal Justice System,” National Conference of State Legislatures, January 2020.

[2] Elizabeth Jones, “Racism, fines and fees and the US carceral state,” Sage Journals Race & Class, October 2017.

[3] DCFPI analysis of DC JSAT jail and prison population statistics.

[4] Fines and Fees Justice Center, “Assessments and Surcharges,” December 2022.

[5] Cameron Kimble and Ames Grawert, “Collateral Consequences and the Enduring Nature of Punishment,” Brennan Center for Justice, June 2021.

[6] Ram Subramanian et. al, “Revenue Over Public Safety: How Perverse Financial Incentives Warp the Criminal Justice System,” Brennan Center for Justice, July 2022.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency for the District of Columbia, “Community Supervision.”

[9] Ibid.

[10] Jill Lepore, “The Invention of the Police: Why did American policing get so big, so fast? The answer, mainly, is slavery.” The New Yorker, July 2020.

[11] Library of Congress, “The slavery code of the District of Columbia,” 1862.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, “Consumer Price Index, 1800-”.

Because official US CPI data goes back to 1913, it is difficult to determine the value of these fines in current dollars. However, using pre-1913 unofficial CPI data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis provides an unofficial estimate of these costs. According to the Minneapolis FED, $5 in 1808 would be approximately $95 and $20 in 1812 would be approximately $359 in 2023 dollars.

[14] J.D. Dickey, “Empire of Mud: The Secret History of Washington D.C.,” Lyons Press, pp. 91-91.

[15] Michelle Alexander, “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness,” The New Press, 2010.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ellen Terrell, “The Convict Leasing System: Slavery in its Worst Aspects,” Library of Congress Blogs, June 2021.

[18] Ibid.

[19] “Convict Leasing,” Equal Justice Initiative, November 2013.

[20] Ryan Moser, “Slavery and the Modern-Day Prison Plantation,” JSTOR Daily, November 2023.

[21] Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Prisoners 1925-81,”

[22] Dr. Ashley Nellis, “Mass Incarceration Trends,” The Sentencing Project, January 2023.

[23] Bruce Western and Becky Pettit, “Incarceration and Social Inequality,” American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2010.

[24] Chris Asch & George Musgrove, “Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital”, University of North Carolina Press, 2017, pp. 404.

[25] DCFPI analysis of DC JSAT MPD Adult Arrest Data, Calendar Year 2023.

[26] DCFPI analysis of DC JSAT jail and prison population statistics.

[27] Michael Sances and Hye Young You, “Who Pays for Government? Descriptive Representation and Exploitative Revenue Sources,” The University of Chicago Press Journals, July 2017.

[28] Adewale A. Maye, “Chasing the dream of equity: How policy has shaped racial economic disparities,” Economic Policy Institute, August 2023.

[29] American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), “Captive Labor: Exploitation of Incarcerated Workers,” June 2022.

[30] Ella Baker Center for Human Rights et. al, “Who Pays: The True Cost of Incarceration on Families,” September 2015.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] United States Census Bureau, “2015 Poverty Thresholds,” 2016.

[34] Peter Wagner and Bernadette Rabuy, “Following the Money of Mass Incarceration,” Prison Policy Institute, January 2017.

[35] Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, 2015.

[36] Leah Wang et. al, “Beyond the count: A deep dive into state prison populations,” Prison Policy Initiative, April 2022.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Tara O’Neill Hayes and Margaret Barnhorst, “Incarceration and Poverty in the United States,” American Action Forum, June 2020.

[39] Craig Haney, “Criminality in Context: The Psychological Foundations of Criminal Justice Reform,” The American psychological Association, January 2020, pp. 7.

[40] Bureau of Prisons, “Inmate Financial Responsibility Program,” August 15, 2005.

[41] Lisa Foster, “The Price of Justice: Fines, Fees and the Criminalization of Poverty in the United States,” University of Miami Race and Social Justice Law Review, November 2020.

[42] Leah Wang and Wanda Betram, “New data on formerly incarcerated people’s employment reveal labor market injustices,” Prison Policy Initiative, August 2022.

[43] Teigen, 2020.

[44] Dick Carpenter et. al, “Municipal Fines and Fees: A 50-State Survey of State Laws,” Institute for Justice, April 2020.

[45] Teigen, 2020.

[46] Fines and Fees Justice Center, “Free to Drive: National Campaign to End Debt-Based License Restrictions,” 2022.

[47] Criminal Justice Policy Program: Harvard Law School, “50-State Criminal Justice Debt Reform Builder: Poverty Penalties and Poverty Traps”.

[48] Department of Corrections, “Inmate Financial Obligations Policy and Procedure,” August 18, 2023, pg. 6.

[49] Ibid, pg. 6

[50] People who receive pay for work performed while incarcerated make between $0.12 and $0.40 per hour in federal facilities, on average. See American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), “Captive Labor: Exploitation of Incarcerated Workers,” June 2022.

[53] Department of Corrections, 2023, pg. 10

[54] Bureau of Prisons, 2005.

This provides the most updated policy guidance for the BOP’s Inmate Financial Responsibility Program (IFRP). In 2023, the BOP proposed a new IFRP policy which has yet to take effect as of the date of this report.

[56] National Institute of Corrections, “Probation and Parole.”

[57] Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency, “FY 2024 Congressional Budget Justification,” Community Supervision Program, pg. 37

[58] Ibid, pg. 35.

[59] Urban Institute, “State and Local Backgrounders: Property Taxes,” April 2023.

[60] Urban Institute, “State and Local Backgrounders: Fines, Fees, and Forfeitures,” April 2023.

[61] DCFPI analysis of FY2025 projected revenues, by revenue source.

[62] DCFPI analysis of FY2025 projected revenues, by revenue source.

[63] “DC to install 342 new automated traffic enforcement cameras: Bowser,” Fox 5 DC, March 2023.

[64] Antonya Jeffrey, “How government reliance on fines and fees harms communities across the United States,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, April 2023.

[65] Ibid.

[66] “Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department,” United States Department of Justice, March 2015.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Jon Bouker, “Appendix I: The DC Revitalization Act: History, Provisions and Promises,” Brookings, 2016.

[69] Peter Wagner and Wanda Bertram, “State of Phone Justice – Appendix Table 3,“ Prison Policy Initiative, December 2022

[70] Tiana Herring, “COVID looks like it may stay. That means prison medical copays must go,” Prison Policy Initiative, February 2022.

[71] “2022-2023 Inmate Handbook,” DC Department of Corrections.

[72] D.C. Code §4–515 subs. C, “Crime Victims Compensation Fund.”

In addition to assessments imposed by the Court, the CVCF also receives annual funding through a federal grant which is based upon payments to crime victims two years prior to the grant award year.

[73] Although DC directs assessments imposed at sentencing towards funds for victims of crime, the Court imposes assessments for everyone convicted, pleading guilty, or “no contest” to a criminal offense even if the offense doesn’t involve a victim. For criminal offenses in which a victim is harmed, the Court also imposes restitution, in addition to and separate from criminal assessments imposed by the Court, which requires a defendant to directly compensate victims harmed as a result of their offense.

[74] D.C. Code §4–515.01, “Crime Victims Assistance Fund.”

[75] “Inmate Admission & Orientation Handbook,” Bureau of Prisons, 2023.

[76] “DOC Fiscal Year 2024 Performance Oversight Responses,” February 2024, pg. 598.

[77] “Inmate Institutional Work Program,” Department of Corrections, 2017.

[78] Wagner and Bertram, 2022.

[79] Avery Bleichfeld, “New state law makes prison phone calls free,” The Bay State Banner, December 2023.

[80] Federal Communications Commission, “Incarcerated People’s Communications Services,” September 2023.

[81] ACLU, 2022.

[82] Martin Austermuhle, “D.C. Inmates Serve Time Hundreds Of Miles From Home. Is It Time To Bring Them Back?,” American University Radio, August 2017.

[83] Commissary is a store with food, hygiene, clothing, and other goods available to residents incarcerated in correctional facilities.

[84] ““We’re Hungry in Here”: DC Department of Corrections Food Survey Results,” DC Greens, November 2023.

[85] “Fiscal Year 2019 DOC Performance Oversight Responses,” Pg. 214.

[86] “Fiscal Year 2024 DOC Performance Oversight Responses,” Pg. 902.

[87] DCFPI Analysis of DOC Concession Income, fiscal years 2018-2023. Adjusted in 2024 dollars. Figures excluded revenues collected from commissary items deposited into the Inmate Welfare Account (0602).

[88] “Food Regulation Ensures Safety and Hospitality Specialty Training Aids Re-entry Transition and Success (FRESH STARTS) Act of 2023,” B25-0112, Introduced on February 2, 2023.

[89] Work release differs from traditional work assignments in DOC facilities as wages earned through work release must meet minimum wage standards. Work release also differs from traditional DOC work assignments as those on work release work outside DOC facilities.

[90] D.C. Code §24–241.01.

[91] D.C. Code §24–241.06.

[92] Department of Corrections, “Inmate Programs and Services,” City of Baltimore.

[93] Detention Facilities, “Inmate Work Release Program,” Anne Arundel County.

[94] DC Office of Tax and Revenue, “Individual and Fiduciary Income Taxes,” Tax Year 2022.

[95] DCFPI analysis of non-tax revenues, FYs 2010-2018. Dollars represented in FY24 dollars.

[96] Office of the Chief Financial Officer, “Non-Tax Revenue Report,” 2015. Pg. 89.

[97] Correspondence from Department of Corrections Staff, September 2023.

[98] Jonah Beleckis, “Wisconsin Prisons Quietly Reinstate Copays For Those With COVID-19 Symptoms,” Wisconsin Public Radio, December 2023.

[99] Office of the Chief Financial Officer, “Non-Tax Revenue Report,” 2015.

[100] Office of the Chief Financial Officer, “Special Purpose Revenue Report,” 2015.

[101] United States Census Bureau, “FOIA Overview.”

[102] Craig Haney, 2020.

[103] “The District Can Raise Critically Needed Revenue by Taxing Wealth,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, February 2024.

[104] Susan Davis, “Congress overturns D.C. crime bill with President Biden’s help,” NPR, March 2023.

[105] “Fines and Fees Reports,” State Compensation Board of Virginia.

[106] Office of Revenue Analysis, “Revenue Overview,” Office of the Chief Financial Officer.

[107] Office of the Chief Financial Officer, “Non-Tax Revenue Report,” 2015.

[108] Office of the Chief Financial Officer, “Special Purpose Revenue Funds Report,” 2015.

[109] Office of Revenue Analysis, “Revenue Overview,” Office of the Chief Financial Officer, FYs 2017-2021.

[110] DCFPI analysis of non-tax revenue data, FYs 2015-2019. Note: Excludes business and non-business license fees, but does not include revenue refunds for FY19.

[111] These revenue sources do not include special purpose revenue sources generated from fines and fees during this period.

[112] “Removing Barriers to Occupational Licensing for Returning Citizens Amendment Act of 2019,” A23-0561, April 2021.

[113] DCFPI email correspondence with DC Council Staff and the Deputy Mayor for Public Safety and Justice, February 2024.

[114] Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, 2015.

[115] Ibid.

[116] DC Department of Corrections, “Inmate Handbook,” July 2022.

[117] City of Philadelphia, “Statement on Elimination of Commissary Fees and Increase in Free Communication at Philadelphia Prisons,” July 2021.

[118] DCFPI analysis of adjusted DOC Concession Income Revenues, FYs 18-23.

[119] D.C. Code § 4–516, Subs. (3).

[120] General District Court, “Fine Options Program,” Fairfax County.

[121] “Project Empowerment Program,” District of Columbia Department of Employment Services.

[122] “Resident Resources,” Mayor’s Office of Community Affairs.

[123] “The District Can Raise Critically Needed Revenue by Taxing Wealth,”

[124] Anika Dandekar and Tenneth Fairclough II, “D.C. Voters Strongly Support Revenue-Raising Policies That Will Ensure Wealthy Households and Businesses Pay Their Fair Share in Taxes,” Data for Progress, April 10, 2024.

[125] S.B. 516, “Fair Wages for Incarcerated Workers Act of 2023,” February 2023.

[126] “Individual Taxpayer Identification Number,” Internal Revenue Service.

An Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) is a tax processing number issued by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The IRS issues ITINs to individuals who are required to have a U.S. taxpayer identification number but who do not have, and are not eligible to obtain, a Social Security number.

[127] Center for Employment Opportunities, “Returning Citizens Stimulus,” accessed March 19, 2024; Ivonne Garcia, Margaret Hennessy, Erin J. Valentine, Jed Teres, Rachel Sander, “Paving the Way Home: An Evaluation of the Returning Citizens Stimulus Program,” MDRC, September 2021.

[128] Garcia et. al, 2021. https://www.ceoworks.org/assets/downloads/RCS-Evaluation-Report.pdf

[129] Ibid, pp ES-5.

[130] Center for Employment Opportunities, “Returning Citizen Stimulus (RCS) Impacts on Long-Term Employment Outcomes,” accessed March 19, 2024.

[131] Nik Theodore, “Chicago Future Fund Round 1 Evaluation,” Chicago Future Fund, November 2023.

[132] Ibid.