This new Council Period, DC policymakers can continue advancements in racial equity (as envisioned in the Racial Equity Achieves Results Amendment Act of 2020) and help build a just economic recovery with recreational cannabis[1] policy.[2] DC’s Black and brown communities are still enduring the harmful effects of past policies that penalized cannabis, and nationally, about 80 percent of people incarcerated for a federal drug offense are Black or Latino. Legalizing the sale of recreational cannabis in a reparative way would allow these communities to achieve justice and build wealth. While the recreational sale of cannabis is still illegal in DC, the office of the DC Attorney General concluded that the District can proceed with legislative hearings on regulating the sale of recreational cannabis despite ongoing congressional interference.[3] The new Democratic-led Senate could also help usher in legislative changes that affirm DC’s right to self-determination in setting recreational cannabis regulation.

When the District chooses to move forward with these hearings, it should include measures to address the historic harm to Black and brown communities that criminalization caused. It should further ensure that access to the new industry is equitable. This requires undoing the harm of prior cannabis arrests and convictions through expungement, creating racially diverse cannabis business and job opportunities, and intentionally using cannabis tax revenue to build community wealth. If designed well, we will be able to create more equity and, in some areas, reparations for the damage past cannabis policy has wrought.

Understanding the history of cannabis policy elucidates the need for us to get this right. Early racist associations connecting cannabis usage to violence in Mexican, Japanese, and Black communities laid the groundwork for cannabis prohibition and the “war on drugs”—both of which fueled unjust over policing and mass incarceration of Black and brown people. Criminalization directly harmed many Black and brown families’ ability to be hired for a job, secure housing, receive federal financial aid for higher education and financial assistance to support their family, drive, own a business, vote, etc. Now is the time to atone for these historical injustices by ushering in a new cannabis industry rooted in equity.

DC has the responsibility to learn from other state’s successes and failures in redressing past injustices and advancing a more equitable industry. These lessons should be fully incorporated into the design and implementation of recreational cannabis policy. As a result, the District should take steps to:

Address Historic and Current Harm:

- Automatically expunge criminal records for cannabis-related DC Code offenses and dismiss pending criminal charges for cannabis-related offenses in the District’s purview. Individuals currently incarcerated locally for cannabis-related DC Code offenses should be automatically released. These efforts should come at no cost to the individual and any incarceration savings should be used to help pay for expungement.

- Establish legal spaces for public cannabis consumption.

- Ensure the equitable access and fair distribution of cannabis dispensaries and cultivation centers in communities.

- Protect cannabis consumers from employer discrimination.

Design a Cannabis Industry that Fosters Racial Inclusion:

- Create an inclusive, independent regulating body to lead the regulation and administration of equitable cannabis law, including requiring that disproportionately harmed individuals and communities be meaningful participants in the cannabis industry and that progress is tracked toward achieving racial inclusion.

- Develop an innovative reparatory licensing program to increase racial diversity in ownership and employment within the DC cannabis industry. Program participants should receive more than half of all available licenses.

- Allow and actively support individuals with criminal records for cannabis-related offenses to seek and obtain employment and entrepreneurship opportunities within the cannabis industry.

Devote Cannabis Tax Revenue to Build Community Wealth:

- Cannabis tax revenue should be used to explicitly benefit individuals and communities disproportionately targeted and harmed by criminalization and the war on drugs. This should include spending the revenue on reparations, expungement, employment and entrepreneurship opportunities, free tuition to the University of the District of Columbia, etc.

Spotlight on Lack of Statehood Implications

At the federal level, cannabis remains a Schedule I substance, which means that it is recognized as high potential for abuse, not legal, and has no accepted medical uses.[4] But DC’s lack of statehood and its unique position as a federal district subject to congressional oversight has hindered its ability to join many states in exercising their right to set their own local cannabis laws.[5] The annual congressional budget rider prohibits DC from spending money to regulate and eliminate penalties associated with possessing, using, or distributing cannabis.[6]As a result, federal cannabis developments particularly matter to the District. For example, within Congress, the House passed legislation in December that would remove cannabis as a Schedule I substance which would essentially make the DC budget rider obsolete.[7] The new Democratic-led Senate could also remove the budget rider from its annual appropriations bill this year.[8]

Current Cannabis Law in the District

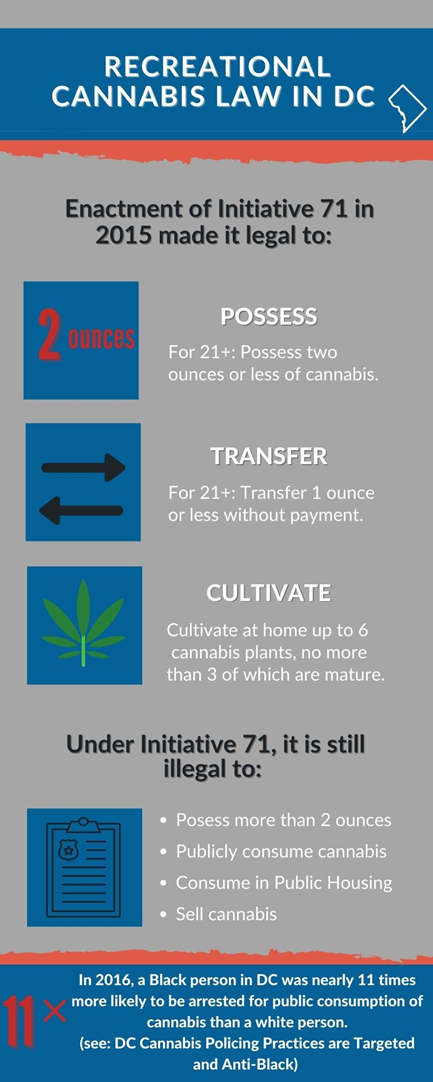

In 1998, District residents approved a voter ballot initiative to legalize the medical use of cannabis. Unfortunately, a longstanding budget rider in the congressional appropriations bill to DC each year, prevented the District from implementing this act until 2010.[9] Five years later, Initiative 71 went into effect, and it legalized the possession of minimal amounts of cannabis in the District for adults aged 21 and older. This voter-approved initiative made it legal for adults to possess, grow and transfer small amounts of cannabis and consume it on private property (Figure 1).[10], [11]

DC appeared poised to move ahead with recreational cannabis sales legislation introduced by both the Council and Mayor Bowser during Council Period 23 in 2019. Former Councilmember David Grosso introduced legislation to legalize recreational cannabis sales every Council term he served, and his last bill was the strongest yet as it addressed historic harm and sought to foster racial inclusion. It included provisions to:

- automatically expunge criminal records that solely involved cannabis;

- develop a dedicated fund from cannabis tax revenue to support drug abuse services and prevention, technical assistance for cannabis businesses, a grant program to community-based nonprofits to support services in communities disproportionately affected by U.S. drug policies, among other supports; and,

- prioritize cannabis licenses for longtime Black DC residents or formerly incarcerated individuals.[12]

The mayor’s bill included few provisions to address historic harm and foster racial inclusion. Unlike the Council bill, it would have automatically sealed cannabis possession records within a year of enactment, not expunge them. (Sealed records still exist in both a legal and physical sense—they are merely removed from public review by restricting access to select groups of people.) The Mayor’s bill would have directed all cannabis tax revenue to affordable housing programs after regulatory costs are paid. And instead of prioritizing licenses for longtime Black DC residents, this bill would have required that 60 percent of license owners and employees be DC residents and it would have prohibited people who have been convicted of a felony drug offense or a serious violent crime from accessing licenses.[13] (The Marijuana Policy Project has produced high-level summaries of both bills.[14], [15])

Historic Harm to Black and Brown Communities

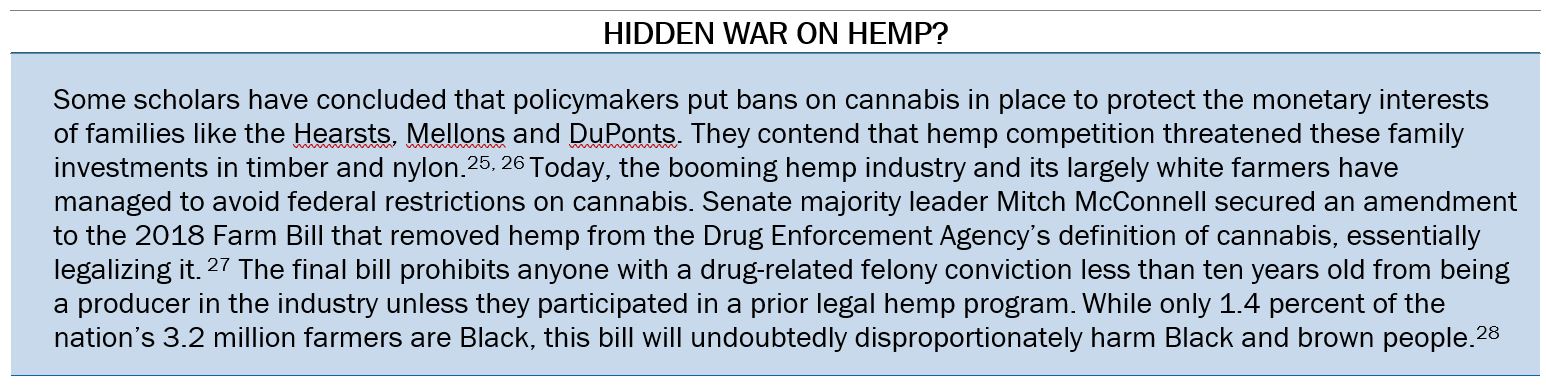

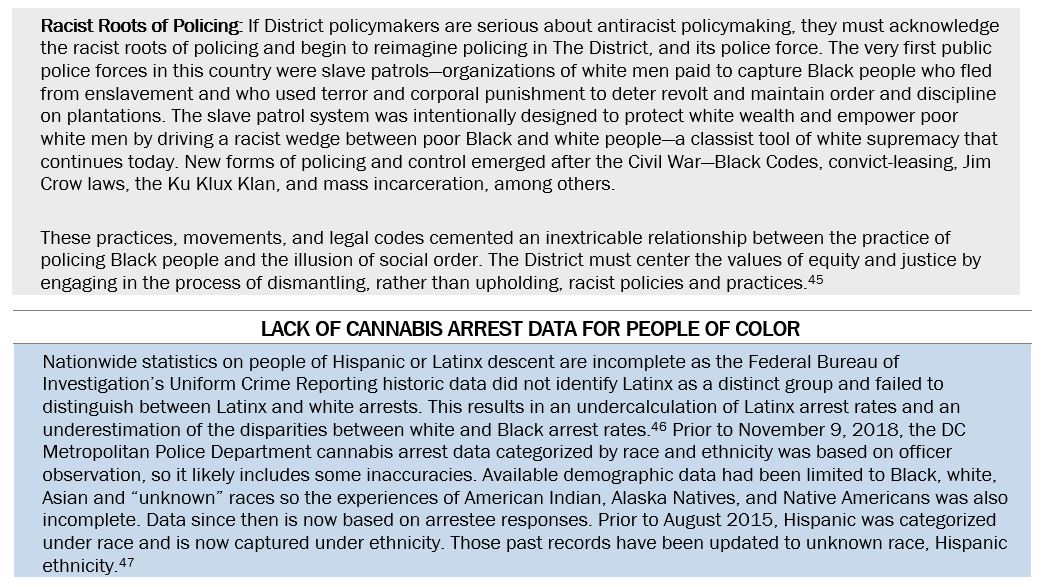

The history of cannabis criminalization is rooted in racism and intentional efforts to harm Black and brown people. Policymakers and the media publicized false causations between cannabis usage and violent crime that helped spur mass incarceration. But once cannabis usage among white consumers grew, federal and state policies shifted toward decriminalization. Today, cannabis policy continues to have deeply harmful effects on these communities of color.

Eastern Origins of Cannabis and Racist Associations in the U.S.

For many thousands of years, Eastern cultures used cannabis for a variety of purposes. Hemp fiber from the plant was used to make clothing, rope, paper, canvas, sails and shoes. People also used cannabis during religious ceremonies, as an anesthetic for surgeries, and as a psychoactive.[16]

By the early 1900s, cannabis usage in the U.S. was primarily concentrated within the southwestern Mexican American community, many of whom had fled the upheaval of the Mexican Revolution. Racist newspaper owners, like William Randolph Hearst, drew false causations between the recreational usage of cannabis by Mexicans and an increase in crime and violence. As a result, the first local ordinance banning the sale or possession of cannabis in El Paso was initiated in 1914.[17] And due to the stigma, the Spanish word for cannabis, “marihuana,” eventually supplanted its scientific name in public discourse.[18]

As Black jazz musicians and Caribbean sailors became new users of cannabis in the 1920s and 1930s, they were also targeted by policymakers and the media. The racist and xenophobic Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) commissioner, Harry Anslinger, rejected scientific conclusions that cannabis was neither a gateway drug nor induced violence.[19] Instead, he sensationally alleged that the “satanic” sounds of jazz were caused by cannabis usage.[20] Anslinger further connected cannabis usage to violent acts, and even later alleged that Japanese people used cannabis to sap the will of U.S. soldiers during World War II. [21]

Fear mongering of cannabis reached its peak with the 1936 propaganda film, Reefer Madness. It claimed that cannabis led to murder, rape, and insanity. Around the same time, Anslinger, and the film industry through propaganda posters, invoked racist imagery by alleging that cannabis led to sexual relations between white women and Black men.[22], [23] The many racist cannabis associations over the decades were followed by federal and local policies restricting the sale and possession of cannabis. By 1931, 29 states had banned cannabis entirely. And the federal 1937 Marijuana Tax Act, criminalized the possession of cannabis throughout the country.[24]

The Reexamination of U.S. Cannabis Policy and the Onset of Mass Incarceration

The emergence of widespread cannabis usage by white middle-class people throughout the 1960s prompted a reexamination of U.S. cannabis policy. In 1970, Congress reduced federal penalties for small amounts of cannabis possession and by 1978, eleven states decriminalized small amounts of cannabis possession.[29], [30] But the prior declaration of a “war on drugs” by President Nixon as a political tool to intentionally disrupt and criminalize the Black community, among others, was difficult to overcome.[31] His administration provisionally designated cannabis a Schedule I substance—which federally recognized it as high potential for abuse with no accepted medical uses. Nixon later rejected the recommendation by his commission that it should be federally decriminalized for personal use.[32], [33]

Federal policies throughout the 1980s increased criminal penalties on cannabis possession, cultivation and trafficking.[34] The administrations of President Reagan, President George H.W. Bush, and President Clinton accelerated Nixon’s war on drugs through mass incarceration at a cost of over $1 trillion since 1971. This pattern has continued well beyond their administrations.[35], [36] Between 1990 and 2010, the number of people arrested nationwide for cannabis offenses increased by 188 percent. In 2010 alone, there were nearly 900,000 arrests for cannabis, which is 300,000 more arrests than those for all violent crimes. And nearly 90 percent of those arrests were for cannabis possession as opposed to distribution. [37]

Black and brown people were disproportionately harmed by those cannabis policies—including being more likely to be arrested and serve harsher sentences despite using cannabis at similar rates as white people. Nationally, about 80 percent of people incarcerated for a federal drug offense are Black or Latino.[38]

DC Cannabis Policing Practices are Targeted and Anti-Black

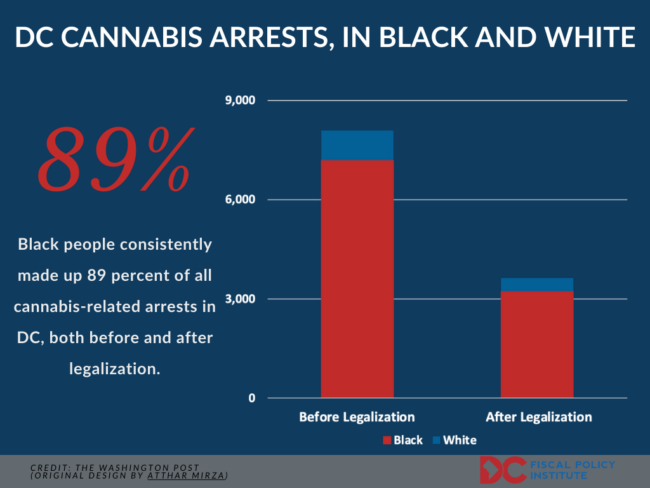

In DC, Black people were overrepresented in arrests for public consumption both before and after Initiative 71. Black people were eight times more likely to be arrested for cannabis possession than white people in 2010—over two times the already high nationwide disparity, according to the ACLU of DC. Police Service Area (PSA) 602 located in the largely Black, lower-income neighborhood of Anacostia had a cannabis arrest rate of 2,488 per 100,000 people while PSA 204 in the largely white, higher income Woodley Park (the PSA with the largest population in 2010) had a cannabis arrest rate of just 33 per 100,000.[39] As a result, Black people represented 91 percent of cannabis possession arrests in DC that year. ACLU DC also found that this racist cannabis enforcement was estimated to cost the District approximately $26 million in 2010.[40]

In 2016, a year after Initiative 71 took effect and possession became legal, a Black person in DC was nearly 11 times more likely to be arrested for public consumption of cannabis than a white person.[41] Similarly, between 2015 and 2017, Black people comprised 80 percent of arrests for public consumption. [42] And while the District began shifting toward citations for many public consumption violations in 2018, the policy is not all inclusive and those cited will still be booked and owe a fine if they decline to fight it in court.[43] Black people still made up 84 percent of arrests for public consumption and 89 percent of all cannabis-related arrests between 2015 and 2019, according to a recent Washington Post study (Figure 2).[44]

Effects of Targeted Criminalization and Mass Incarceration

As the Nixon administration intended, the war on drugs and mass incarceration disrupted entire communities. It birthed a formalized system of social control, primarily of Black and Brown people.[48] Today, prior arrests and incarceration for cannabis-related offenses across the U.S. have had devastating effects on a person’s ability to be hired for a job, secure housing, receive federal financial aid for higher education and financial assistance to support their family, access physical and mental health supports, vote, drive, own a business, and more (Figure 3). These collateral consequences are often familial and intergenerational, leading to greater risk of housing instability, including homelessness, and economic insecurity not only for the individual directly affected, but also spouses, partners and children.[49], [50], [51]

There is no doubt that thousands of DC residents, mostly Black and brown, are dealing with these consequences. Although DC has restored the rights of its residents to vote while incarcerated, allows those who were formerly incarcerated to receive some public assistance, and has taken strides to lessen employer discrimination, returning citizens still face many challenges reintegrating into society, especially given the complicated landscape of both local and federal jurisdictions at play.[52],[53],[54]

One such challenge is securing housing—perhaps, the most important need for returning citizens.[55]

Most returning citizens are released from prison without any savings and without a job, and as a result they lack funds for housing application fees, security deposits, and rent. They also face high rates of discrimination in the housing market. Almost one-third of individuals who experience homelessness in DC directly connect that to their prior incarceration.[56]

Legalization without Intentionality Will Further Structural Racism

“Is it the fault of today’s well-funded, legal, and largely white cannabis entrepreneurs that the US criminal justice system spent decades punishing black offenders at wildly disproportionate rates? No. But just as white Americans prosper disproportionately from an economy built upon slavery, redlining, and other forms of institutionalized racism, the marijuana industry’s astronomical growth comes with an ugly history—and present reality—of racial oppression.” -Jenni Avins, Quartz[57]

The legalization of recreational cannabis sales will create more jobs, businesses, and wealth. But given that structural racism is designed to create and protect wealth for white people and deny it to Black people and other people of color—combined with the specific economic harm for people of color created by prior cannabis policy—simply opening up this industry without intentionality will exacerbate inequities.[58] This context matters for the burgeoning cannabis industry.

Today, Black ownership of storefront cannabis dispensaries is estimated to be around one percent nationwide.[59] Another survey found that the percentage of Black and brown people that have launched a cannabis business and/or have any (not controlling) ownership stake in a cannabis business, is slightly higher at four and six percent, respectively.[60] This is partly because the upfront costs to start a legal cannabis business are often extremely high and the federal restrictions on cannabis prevent access to small business loans from banks. This directly causes ownership inequities and negatively impacts Black and brown people who have historically been locked out of wealth-building opportunities that white people freely received.

While Black ownership and people of color ownership of dispensaries and a cultivation center are represented in DC’s medical cannabis industry, policymakers should still make sure they legislate with an eye for dismantling structural racism, baked into the design of policies and policing practices.[61], [62], [63], [64]

Recommendations

Any legislation that is put forth before the DC Council to legalize and regulate the sale of recreational cannabis should include three crucial elements: address historic and current harm; design a cannabis industry that fosters racial inclusion; and devote cannabis tax revenue towards reparations and to build community wealth.

Without intentionality, the growing cannabis industry will exacerbate inequity. So, policymakers should be intentional about finding ways to ensure that the industry is equitable and racially diverse. While there is no uniform approach to doing this, DC can learn from existing state efforts and devise new ways to contribute to burgeoning state recreational cannabis policy.

Address Historic and Current Harm

1. Automatically expunge criminal records for cannabis-related DC Code offenses and dismiss pending criminal charges for cannabis-related offenses in the District’s purview. Individuals currently incarcerated locally for cannabis-related DC Code offenses should be automatically released. These efforts should come at no cost to the individual and any incarceration savings should be used to help pay for expungement.

The Council has considered several pieces of legislation to amend the District’s current stringent and complex process of sealing and expunging criminal records (for both convictions and non-convictions).[65], [66], [67], [68], [69] The current process includes few cases of eligibility and long waiting periods for those who do qualify. While current law allows for sealing of criminal offenses that have been decriminalized or legalized, DC law should automatically expunge criminal records for cannabis-related DC Code offenses.[70] And policymakers should include this expungement policy in the bill that legalizes the sale of recreational cannabis, rather than exploring it in a separate measure afterward. Additionally, policymakers should dismiss pending criminal charges for cannabis-related offenses in its purview. These efforts can be achieved without tackling any additional charges that may have been incurred at the time of the offense.

Given our unique status as a District, the savings associated with decarceration for these offenses is lower than that of many states since many of our residents are housed in federal prisons. However, the District can save on short-term misdemeanor offenses related to cannabis, such as possessing more than two ounces, that result in the offender being placed at DC Department of Corrections (DOC) facilities.

Illinois recently became the first state to legalize the sale and consumption of recreational cannabis through the state legislature and policymakers included a provision to automatically expunge some 800,000 cannabis-related criminal records.[71] A share of its cannabis tax revenue will be dedicated toward expungement and administration. California counties such as Los Angeles, Sacramento, San Francisco and San Joaquin, as well as Cook County, Illinois are partnering with Code for America on their Clear My Record digital technology initiative to automatically expunge certain cannabis records.[72] The District should explore the use of similar technology and cover the cost of expungement and administration through cannabis tax revenue and decarceration savings.

Finally, the Council for Court Excellence (CCE) has shown that employers can still find out about an expunged record partly because private companies may not purge information they had previously gathered. This can cause employers to make employment decisions based on false or incomplete information. CCE recommended that the District take steps to require private companies to purge information about arrest and conviction data for records that are expunged.[73] The DC Council introduced a bill in 2017 and 2019 to prohibit these data providers from reporting on records that have been sealed, expunged, or resulted in non-conviction and to establish penalties for non-compliance.[74], [75] This bill should be re-introduced and advanced through the legislative process this Council period.

2. Establish legal spaces for public cannabis consumption.

It is still illegal to consume cannabis publicly in the District. But many District residents who rent and live in federally subsidized housing, or lack permanent housing, do not have access to private spaces for consumption. These residents should still have the freedom to indulge, regardless of their income or whether they own a home. Therefore, the District should legalize spaces for social consumption. These spaces can function similarly to a hookah or cigar lounge. In addition to District residents, tourists without access to private consumption spaces are likely to frequent these lounges and clubs—further increasing local revenue.

In 2016, the DC Council passed legislation to prohibit public consumption of cannabis, including in private clubs.[76] This preempted the work of DC’s Marijuana Private Club Task Force that had been charged with developing recommendations regarding the operation and potential licensing of venues for cannabis consumption, particularly private clubs.[77] The task force eventually concluded that for a number of reasons, including the zoning and business regulation challenges that result from cannabis still being illegal at the federal level, it was premature to advocate for cannabis private clubs at that time.[78]

Once the sale of recreational cannabis is legalized locally, the District should resume efforts to determine how to best authorize public spaces for cannabis consumption to prevent the law from discriminating against renters, public housing residents, and people experiencing homelessness. If no changes are made to existing law, it will continue to disproportionately exclude Black and brown people who make up the majority of public housing residents and our unhoused neighbors.

3. Ensure the equitable access and fair distribution of cannabis dispensaries and cultivation centers in communities.

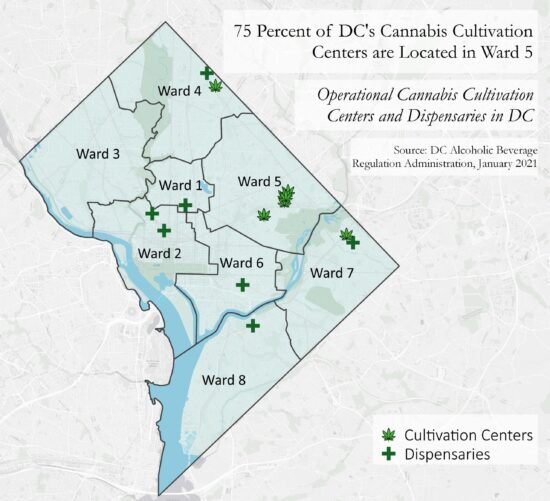

The District should monitor the placement of cannabis dispensaries and cultivation centers to ensure equitable access and fair distribution in communities. There are currently seven operational cannabis dispensaries in the District. However, prior to the opening of the final two dispensaries in wards 7 and 8, registered medical cannabis patients living east of the Anacostia river had to travel far to receive their medication.[79] The District commendably increased the cap on the number of dispensaries from five to seven and required that the additional two dispensaries be located in wards 7 and 8. And largely due to zoning requirements that dictate where cultivation centers can be housed for the medical cannabis program, six of the eight cannabis cultivation centers are located in ward 5 (Figure 4).[80], [81] Community concern about this overconcentration again prompted DC Council changes that limited the number of cultivation centers by ward. In the future, the District should use similar reflective decision-making to ensure equitable access to dispensaries and fair distribution.

Undersaturation and oversaturation of these facilities and past harm of Black and brown communities warrants future monitoring and exploration to define what is fair and equitable in this context. Scholars have begun to study the new relationship between race, zoning, and cannabis, including the phenomenon of low-income communities burdening the production of cannabis while the capital it creates flows out to wealthier neighborhoods.[82] Nationwide, the opposition against the fight to ensure the fair distribution of dispensaries is starting to resemble traditional Not-In-My-Backyard (NIMBY) sentiments about affordable housing. Residents in California and Colorado have alleged that dispensaries and cultivation centers cause lower property values and a disruption in the quality of life.[83] But studies have shown that homes located near cannabis dispensaries have appreciated in Colorado and Washington.[84], [85]

DC law continues to limit the number of dispensaries and cultivation centers in wards, including stipulating that there can be no more than one dispensary in wards that house five or more cultivation centers, like ward 5.[86] However, in the future, the Council should further preempt any NIMBY roadblocks by partnering with the Office of Planning to approve zoning changes that lead to fair distribution and access across the District. And any future dispensary and cultivation center placement in wards 7 and 8 should be paired with significant anti-displacement strategies and local hiring practices to mitigate the negative effects of economic development, and rising land costs and property values.

4. Protect cannabis consumers from employer discrimination.

In 2020, the District passed legislation to establish employment protections for DC government employees who participate in the medical cannabis program.[87] The law prohibits DC government from taking adverse employment action against an employee that participates in a medical cannabis program, unless the employee is impaired at work. While participants who work in safety-sensitive occupations are not included in these protections, the law has codified for the first time a stricter, more limited definition of safety-sensitive and creates a path for these employees to appeal their position’s safety-sensitive designation.[88] It also requires agencies to accommodate employees who participate in the medical program and this could include transferring an employee from a safety-sensitive position to a non-safety sensitive one.

The Council also considered, but ultimately did not pass, legislation that would have eliminated cannabis testing as a condition of employment, given that it is legal to consume cannabis on private property and on personal time. The proposed legislation would have addressed this conflict by prohibiting public and private employers from testing for cannabis usage at the hiring stage, except as required by federal law and for certain positions including safety-sensitive ones.[89] The committee report for the employment protections bill that passed acknowledged that there is no reliable test for cannabis impairment as urinalysis measures presence of cannabis—not impairment, frequency, nor amount of use. Given that there is no way to measure anything other than presence, cannabis usage remains prohibited for employees holding safety-sensitive positions. Employers can also continue to use the flawed urinalysis cannabis tests as a condition of employment.

In the future, the DC Council should expand employment protections to be inclusive of recreational cannabis users at all stages of the employment process and to employees working in the private sector. The District Department of Human Resources should also take steps to annually ensure that safety-sensitive occupations throughout District agencies are appropriately categorized.

Design a Cannabis Industry that Fosters Racial Inclusion

5. Create an inclusive, independent regulating body to lead the regulation and administration of equitable cannabis law, including requiring that disproportionately harmed individuals and communities be meaningful participants in the cannabis industry and that progress is tracked toward achieving racial inclusion.

It is imperative that individuals most harmed by criminalization be represented at the top of the independent body that will lead the regulation and administration of equitable cannabis policy. Last year, the Mayor and Council moved regulatory and licensing oversight of the District’s medical cannabis program from the Department of Health to the independent Alcoholic Beverage Regulation Administration (ABRA).[92] This likely means that ABRA will assume regulatory authority for recreational cannabis as well, especially given that the Mayor’s Safe Cannabis Sales Act of 2019 proposed changing ABRA to the Alcoholic Beverage and Cannabis Administration. But because cannabis is not alcohol and the fact that a reparatory lens should be incorporated, the District should take steps to ensure that the individuals setting regulations for cannabis policy have the required expertise and competency.

Currently, the seven-member Alcohol Beverage Control Board oversees and administers the medical program. The board members are appointed by the Mayor and confirmed by the Council for a four-year term and the members can be reappointed once their term expires.[93] However, there are a number of ways that policymakers can amend the current board structure to be more inclusive. Massachusetts legislators, for example, created a Cannabis Control Commission that consists of five commissioners that are each appointed by different members of the government, based on their expertise. [94] For example, the treasurer and receiver general appoints one member with experience in corporate management, finance or securities. DC policymakers could require that the Council, Mayor, DC Attorney General, and the DC community each appoint at least one member. And our body as a whole should have expertise with cannabis policy, racial equity, social justice, the law, public health, public safety, and finance.

The District already requires that a medical cannabis certified business enterprise have one or more owners be economically disadvantaged or been subjected to racial or ethnic prejudice, whose income does not exceed $349,999, and individually or collectively own at least 60 percent of the licensed business enterprise.[95] The District can expand on that model by requiring that 60 percent of the regulatory authority be represented by long-time residents from disproportionately harmed communities and/or with experience with the criminal justice system. The appointers should take steps to ensure that the body is racially diverse and gender inclusive. This body should not discriminate against people with prior cannabis-related records, arrests, or convictions.

The District should also mandate in legislation that the body be required to track progress toward achieving racial and gender inclusion by collecting and publicly releasing detailed annual data. This should at the very least include demographic data on license applicants and awardees, employees, and business owners. The body should be encouraged to make corrective legislative changes, by partnering with the Council as needed, to ensure an inclusive and equitable industry. This work would complement the Council’s decision to incorporate racial equity as a key focus of DC government, as envisioned in the Racial Equity Achieves Results (REACH) Amendment Act of 2020.[96]

6. Develop an innovative reparatory licensing program to increase racial diversity in ownership and employment within the DC cannabis industry. Program participants should receive more than half of all available licenses.

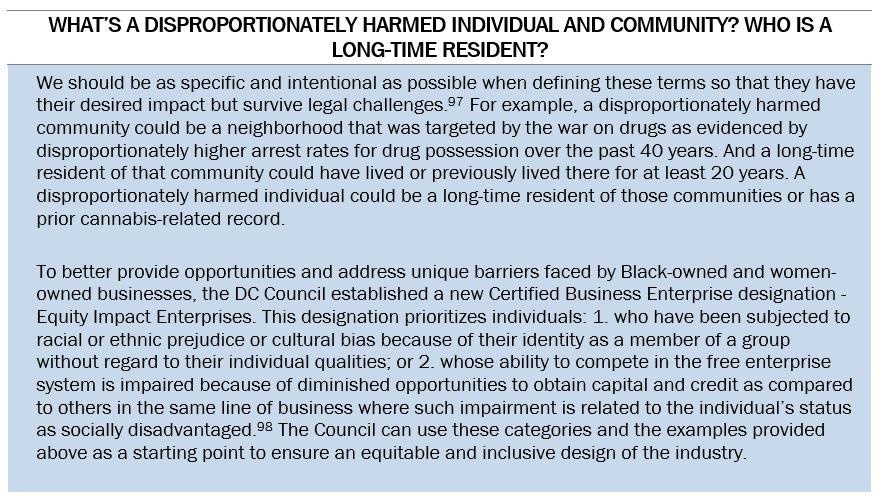

A reparatory licensing program rooted in justice and paired with deep investments would provide disproportionately impacted communities lower barriers to entry and the opportunity to work and own in this new industry. Many states and localities have already developed social equity programs for licensure with limited success because structural racism makes access to a license just one of many barriers facing Black and brown people.

Cities and states like Oakland, Los Angeles, Massachusetts, Illinois have established social equity programs that include fee waivers, financial and technical assistance, a fast-tracked application process, and job placement assistance.[99] Some of these cities as well as others like Sacramento are also inclusive of participants with prior cannabis related convictions dating back to 1980. [100] Massachusetts recently started reserving social consumption and delivery licenses for social equity and economic empowerment applicants for three years, to improve upon its equity outcomes.[101] This demonstrates the value in data collection and the ability to make corrections.

But overall equitable outcomes are still lacking. As detailed previously, the cannabis industry is still overwhelmingly white. And prospective Black cannabis businessowners and supportive policymakers in Los Angeles, Chicago, Maryland and Massachusetts continue to lament the lack of Black and brown participation in this industry.[102], [103], [104], [105]

The District should not become another jurisdiction that fails to get this right. Early experience with medical dispensary licensing demonstrates that it has had some success, and took corrective actions, to ensure that communities of color are represented in the industry.[106] It should build on these efforts by designing a reparatory licensing program. To survive legal challenges, these participants should be long-time residents of a disproportionately targeted community and/or have a prior cannabis-related record. Because these targeted individuals and communities have seen most of the harm of our past drug policies, DC should require program participants to receive more than half of all available licenses in all parts of the supply chain – cultivation, retail, delivery, social consumption, etc.

The District should also provide a sizeable investment to support technical assistance, fee waivers, and grants and interest-free loans for reparatory program participants. And this initial capital should be leveraged by District partnerships with the private sector. The District could also require at least 25 percent of licensee employees be from a disproportionately impacted community or have prior cannabis-related records. Existing dispensary licenses could be grandfathered into the program in a second phase so that new entrepreneurs have an opportunity to receive a license and compete.

The District should also explore additional cooperative ownership models to achieve equity in cannabis. This may help decrease the economic barriers that Black and brown people face by spreading financial risk across the collective and leveraging the strengths of individual members.[107]

7. Allow and actively support individuals with criminal records for cannabis-related offenses to seek and obtain opportunities within the cannabis industry.

The District should not discriminate against individuals with criminal records for cannabis-related offenses. Their prior involvement with cannabis should be a skill, not another penalty. And for those individuals who are returning citizens, the District should be making it easier to reintegrate into society not harder. These individuals should have an opportunity to make a living and share in the prosperity of the new industry. Again, these opportunities should be available in all parts of the supply chain, from cultivation and retail to delivery and social consumption. The District should continue to allow home grown opportunities as well.

Last October, the DC Council introduced legislation to prohibit the repeal on returning citizens working in the medical cannabis industry.[108] This bill also included provisions to provide applicants and approved applicants for a dispensary, cultivation center, and testing laboratory with at least 51 percent ownership by returning citizens with application fee waivers, technical assistance, and assistance in developing a business plan.[109] It would have also provided those applicants with application preference points. This bill should be re-introduced this Council period, expanded to include the recreational cannabis industry, and enacted.

Devote Cannabis Tax Revenue to Build Community Wealth:

8. Cannabis tax revenue should be used to explicitly benefit individuals and communities disproportionately targeted and harmed by criminalization and the war on drugs. This should include spending revenue on reparations, expungement, employment and entrepreneurship opportunities, free tuition to the University of the District of Columbia, etc.

The profits of a legal cannabis industry should overwhelmingly benefit the individuals and communities that racist drug policy harmed for decades. Marijuana Policy Trust advocates for cannabis tax revenue to support a comprehensive package to build and strengthen the Black middle class and community, in a similar way that the GI Bill and Federal Housing Administration loans built and bolstered the white middle class.[110] Marijuana Policy Trust also recommends innovative approaches such as forming cannabis cultivation and research partnerships with local historically Black colleges and universities.

While the amount of cannabis tax revenue generated in DC will be too small to reach this scale, the revenue raised can help supplement existing, and often dwindling, federal and local funding that Black and brown communities receive. Leaders in Evanston, Illinois plan to explicitly use their cannabis tax revenue to fund race-based reparations that not only takes into consideration the war on drugs but also redlining, Jim Crow, and the recent foreclosure crisis.[111] A coalition of Black leaders in New Jersey are demanding that the newly legalized recreational cannabis industry include economic reparations for communities of color.[112] And a white Virginian policymaker recently called for all future cannabis tax revenue in his state to go to reparations for Black and indigenous Virginians as a moral commitment to our history.[113]

The DC Council introduced legislation last year to study and develop reparation proposals for Black Americans. When reintroduced, the war on drugs and future recreational cannabis revenue should be a part of those proposals.[114]

The District should use cannabis tax revenue to support:

-

- Reparations

- The cost of automatic expungement for cannabis-related offenses

- Targeted hiring within the public sector for returning citizens and those affected by the war on drugs

- Homebuyer down payment assistance programs specifically for those harmed by past racist policies

- Reentry services, perhaps through the Mayor’s Office on Returning Citizen Affairs

- Free tuition at the University of the District of Columbia specifically for those harmed by past racist policies

- Community-driven asset mapping to determine future needs

- Small business creation and expansion

The District should also legislate and allocate funding from the General Fund to support immediate outreach and education on these services and programs.[115]

This report would not be possible without the generous insight and time of the following people: Khadijah Tribble, Marijuana Policy Trust, Marijuana Matters, & Curaleaf; Commissioner Shaleen Title, Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission; Lisa Scott, DC Cannabis Business Association; Queen Adesuyi, Drug Policy Alliance; Rafi Crockett, Alcohol Beverage Control Board; Omar Allen, Herb ‘n’ Organics; Ben Murphy and Dawnn Leary, Greater Washington Community Foundation; Emily Price, So Others Might Eat (formerly); Social Equity in Cannabis members from 2019 meeting held at We Act Radio; James Pittman, Office of the Attorney General for the District of Columbia (formerly); Evette Banfield, Coalition for Nonprofit Housing and Economic Development; Maya Kearney, American University; Temi Bennett, Consumer Health Foundation; Qubilah Huddleston, DC Fiscal Policy Institute; Shayla Thompson, National Employment Law Project; Emily Tatro, Council for Court Excellence

[1] The author chose to use the race-neutral scientific term “cannabis” throughout this report except in reference to official bill titles, commissions and organizations.

[2] Council of the District of Columbia, Racial Equity Achieves Change Amendment Act of 2020, B23-0038, Final Reading November 10, 2020.

[3] Rachel Kurzius, Mayor Bowser Introduces A Plan To Get Recreational Weed Dispensaries In D.C., DCist, May 2, 2019.

[4]German Lopez, Marijuana is illegal under federal law even in states that legalize it, Vox, November 14, 2018.

[5] Karl A. Racine and David Grosso, Congress, stop blocking D.C. from regulating its marijuana market, The Washington Post, April 12, 2019.

[6] US Congress, S.2524 – Financial Services and General Government Appropriations Act, 2020, Title VIII – General Provisions District of Columbia, September 19, 2019.

[7] Deirdre Walsh, House Approves Decriminalizing Marijuana; Bill To Stall In Senate, NPR, December 4, 2020.

[8] Natalie Fertig, Democratic-led Senate could clear a path to marijuana legalization, Politico, January 8, 2021.

[9] Code of the District of Columbia, Title 7, Chapter 16B. Use of Marijuana for Medical Treatment – Editor’s Notes: History of D.C. Law 13-315, Current through Feb. 21, 2020.

[10] Electors of the District of Columbia, Initiative 71 – Legalization of Possession of Minimal Amounts of Marijuana for Personal Use Initiative of 2014, L20-0153, Effective from Feb 26, 2015.

[11] Government of the District of Columbia, Initiative 71 and DC’s Marijuana Laws: Questions and Answers.

[12] Council of the District of Columbia, Marijuana Legalization and Regulation Act of 2019, B23-0072, Introduced January 8, 2019.

[13] Council of the District of Columbia at the request of the Mayor, Safe Cannabis Sales Act of 2019, B23-0280 Introduced May 6, 2019.

[14] Marijuana Policy Project, The Marijuana Legalization and Regulation Act of 2019 Summary, 2019.

[15] Marijuana Policy Project, Summary of D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser’s Safe Cannabis Sales Act of 2019, 2019.

[16] Barney Warf, “High Points: An Historical Geography of Cannabis,” Geographical Review, 104 (4): 418-421, October 2014.

[17] Warf, pg. 429.

[18] Laura Smith, How a racist hate-monger masterminded America’s War on Drugs, Timeline, February 28, 2018.

[19] Warf, pg. 429 – 430.

[20] Smith.

[21] Eric Schlosser, “Reefer Madness,” The Atlantic, August 1994 Issue.

[22] Warf, pg. 430

[23] Smith.

[24] Schlosser.

[25] Laurence French and Magdaleno Manzanárez, Nafta & Neocolonialism: Comparative Criminal, Human & Social Justice, University Press of America, 2004, pg. 129.

[26] Mitch Earleywine, Understanding Marijuana: A New Look at the Scientific Evidence, Oxford University Press, August 15, 2002, pg. 24.

[27] Kit O’Connell, The Felony Ban: Behind the Original Sin of the 2018 Farm Bill, HEMP Magazine: Issue 7, August 2019.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Schlosser.

[30] Warf, pg. 430-431.

[31] Dan Baum, Legalize It All: How to win the war on drugs, Harper’s Magazine, April 2016 issue.

[32] Warf, pg. 431.

[33] David Downs, The Science behind the DEA’s Long War on Marijuana, Scientific American, April 19, 2016.

[34] Schlosser.

[35] Betsy Pearl, Ending the War on Drugs: By the Numbers, Center for American Progress, June 27, 2018.

[36] American Civil Liberties Union, The War on Marijuana in Black and White, June 2013, pg. 89.

[37] Ibid, pg. 7-13.

[38] Pearl.

[39] American Civil Liberties Union, Behind the D.C. Numbers: The War on Marijuana in Black and White, Revised July 2013, pg. 4-5.

[40] Ibid, pg. 5.

[41] Drug Policy Alliance, From Prohibition to Progress: A Status Report on Marijuana Legalization, January 2018, pg. 33-34

[42] ACLU DC, Racial Disparities in D.C. Policing: Descriptive Evidence From 2013-2017, Updated July 31, 2019.

[43] Office of the Mayor, Mayor Bowser Implements Policy to Reduce Number of People Taken into Custody for Public Consumption of Marijuana, September 21, 2018.

[44] Paul Schwartzman and John D. Harden, D.C. legalized marijuana, but one thing didn’t change: Almost everyone arrested on pot charges is Black, The Washington Post, September 15, 2020.

[45] Kate Coventry, Doni Crawford, Eliana Golding, Danielle Hamer, Qubilah Huddleston, and Alyssa Noth, How Divesting from the Police Can Strengthen the District, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, June 12, 2020.

[46] American Civil Liberties Union – June 2013, pg. 32.

[47] DC Metropolitan Police Department, Explanatory Note on Marijuana Arrest Data, May 12, 2020, pg. 1-3.

[48] Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration, The Atlantic, October 2015 Issue.

[49] The National Research Council of the National Academies, The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences, Chapter 9 – Consequences for Families and Children, 2014.

[50] Bruce Western and Becky Pettit, “Incarceration & social inequality,” Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, Summer 2010.

[51] U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Collateral Consequences: The Crossroads of Punishment, Redemption, and the Effects on Communities, June 2019.

[52] Martin Austermuhle, D.C. Clears The Way For Incarcerated Felons To Vote, Joining Only Two States That Allow It, DCist, July 9, 2020.

[53] Public Welfare Foundation, D.C.’s Justice Systems: An Overview, October 2019, pg. 5-7, 14-17.

[54] Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights & Urban Affairs, The Collateral Consequences of Arrests and Convictions under D.C., Maryland, and Virginia Law, October 22, 2014, pg. 7-10, 18.

[55] Maya S. Kearney, M.A.A., Ethnographic Assessment of the DC Mayor’s Office on Returning Citizen Affairs, The Cultural Systems Analysis Group, University of Maryland, revised 2015, pg. 17.

[56] Kate Coventry, Coming Home to Homelessness, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, February 27, 2020, pg. 1

[57] Jenni Avins, In the age of luxury cannabis, it’s time to talk about Drug War reparations, Quartz, January 25, 2019.

[58] Doni Crawford, Black Workers Matter: How the District’s History of Exploitation & Discrimination Continues to Harm Black Workers, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, January 28, 2020, pg. 4, 12.

[59] Amanda Chicago Lewis, America’s Whites-Only Weed Boom: How Black People are Being Shut Out of America’s Weed Boom – Whitewashing the Green Rush, BuzzFeed News, March 16, 2016.

[60] Marijuana Business Daily, Women & Minorities in the Marijuana Industry, September 2017, pg.10

[61] John Schroyer and Linda Mercado Greene, Black marijuana business executives address bigotry in the sector, Marijuana Business Daily, June 29, 2020.

[62] National Holistic Healing Center, Meet Dr. Chanda, 2020.

[63] We Are the Cannabis Industry, Corey Barnette, 2017.

[64] Martin Austermuhle, Second Marijuana Dispensary Opens East Of The Anacostia River In D.C., WAMU, August 15, 2019.

[65] Joshua Kaplan, In D.C., Sealing Your Criminal Record Can Be Harder Than Almost Anywhere Else, Washington City Paper, November 20, 2019.

[66] Office of DC Councilmember David Grosso, Fact Sheet: Record Sealing Modernization Amendment Act of 2019, January 8, 2019.

[67] DC Justice Lab, #SealTheDeal Fact Sheet, October 2020.

[68] Public Welfare Foundation, D.C.’s Justice Systems: An Overview, October 2019, pg. 28.

[69] Jamison Koehler, Expungement/Sealing of Criminal Records in D.C., Koehler Law, 2020.

[70] Council for Court Excellence, Beyond Second Chances: Returning Citizens’ Re-Entry Struggles and Successes in the District of Columbia, December 2016, pg. 44.

[71] Natalie Fertig, Cannabis: The Essential Guide, PoliticoPro, October 2019, pg. 17.

[72] Kira Lerner, Chicago’s Top Prosecutor: Clearing Marijuana Records Will Be ‘Life-Changing, The Appeal, August 30, 2019.

[73] Council for Court Excellence, pg. 44-45, 56.

[74] Council of the District of Columbia, Criminal Record Accuracy Assurance Act of 2019, B23-0005, Introduced January 3, 2019.

[75] Council of the District of Columbia, Criminal Record Accuracy Assurance Act of 2017, B22-0404, Public Hearing on December 14, 2017.

[76] Code of the District of Columbia, Title 48, Chapter 9A. Marijuana Consumption in Public Space., Current through November 17, 2020.

[77] Benjamin Freed, DC Bans Private Marijuana Clubs, Making Legalization Even Murkier, Washingtonian, April 17, 2019.

[78] Department of Health, Marijuana Private Club Task Force Report 2016, 2016, pg. 2-3, 27.

[79] Martin Austermuhle, Second Marijuana Dispensary Opens East of The Anacostia River In D.C., WAMU, August 15, 2019.

[80] Alcoholic Beverage Regulation Administration, Medical Cannabis Program Update, January 27, 2021.

[81] Martin Austermuhle, No Medical Marijuana Cultivation in Ward 7! D.C. Council Moves Against Hopeful Cultivator, DCist, March 20, 2012.

[82] Alexis Holmes, Zoning, Race, and Marijuana: The Unintended Consequences of Proposition 64, Lewis & Clark Law Review, Vol. 23:3, 2019, pg. 939-966.

[83] Brooke Staggs, Marijuana stinks. Here’s what cities, businesses and neighbors can do about it, Orange County Register, November 21, 2018.

[84] Ben Adlin, Legalizing Marijuana Increases Housing Prices, Study Finds, Marijuana Moment, March 14, 2020.

[85] David Downs and Bruce Barcott, Special Report: Debunking Dispensary Myths, Leafly, May 2019.

[86] Code of the District of Columbia, Chapter 16B. Use of Marijuana for Medical Treatment. § 7–1671.06. Dispensaries and cultivation centers, Current through November 17, 2020.

[87] Council of the District of Columbia, Medical Marijuana Program Patient Employment Protection Amendment Act of 2020, B23-309, Transmitted to the Mayor on December 8, 2020.

[88] DC Committee on Labor and Workforce Development, Committee Report on B23-309, “Medical Marijuana Program Patient Employment Protection, October 27, 2020.

[89] Council of the District of Columbia, Prohibition of Marijuana Testing Act of 2019, B23-0266, Public Hearing on September 25, 2019.

[90] Aja Beckham, These D.C. Weed Workers Are The First Local Dispensary Employees To Unionize, DCist, October 22, 2020.

[91] United Food and Commercial Workers Local 400, Workers Unionize First Solely Black-Owned Cannabis Dispensary in Washington, D.C., October 21, 2020.

[92] Council of the District of Columbia, Fiscal Year 2021 Budget Support Act of 2020, DC Act 23-407, August 31, 2020.

[93] Code of the District of Columbia, Title 25. Alcoholic Beverages, § 25–206. Board member qualifications; term of office; chairperson; conflict of interest, Current through November 17, 2020.

[94] Massachusetts Legislature, Chapter 55: An Act to Ensure Safe Access to Marijuana, Approved by the Governor, July 28, 2017.

[95] Code of the District of Columbia, Chapter 16B. Use of Marijuana for Medical Treatment. § 7–1671.06. Dispensaries and cultivation centers, Current through November 17, 2020.

[96] Council of the District of Columbia, Racial Equity Achieves Change Amendment Act of 2020, B23-0038, Final Reading November 10, 2020.

[97] John Eligon, A Covid-19 Relief Fund Was Only for Black Residents. Then Came the Lawsuits., The New York Times, January 3, 2021.

[98] Doni Crawford and Eliana Golding, What’s In the FY 2021 Approved Budget for an Inclusive Economy? , DC Fiscal Policy Institute, September 17, 2020.

[99] Eli McVey, Chart: Not all states’ cannabis social equity programs are equal, Marijuana Business Daily, August 20, 2019.

[100] Sacramento City Council, Establish the Cannabis Opportunity Reinvestment and Equity (CORE), August 9, 2018.

[101] Jessica Bartlett, After outcry, cannabis regulators seek to prioritize small business, Boston Business Journal, September 13, 2019.

[102] Sam Levin, ‘This was supposed to be reparations’: Why is LA’s cannabis industry devastating black entrepreneurs?, The Guardian, February 3, 2020.

[103] Justin Laurence, West Loop Alderman’s Message To Weed Dispensary Owners: Get A Black Partner Or Don’t Come To My Ward, Block Club Chicago, December 5, 2019.

[104] Brentin Mock, Race and Weed in Maryland, CityLab, May 4, 2017.

[105] Zeninjor Enwemeka, Black Entrepreneurs Call For More Equity In Mass. Cannabis Industry, WBUR Bostonomix, September 5, 2019.

[106] John Schroyer and Linda Mercado Greene.

[107] Khadijah Tribble, Memo on Worker-Owned Cooperative Solutions in Cannabis, Marijuana Matters, July 12, 2019.

[108] Council of the District of Columbia, Returning Citizens Cannabis Equity Amendment Act of 2020 , B23-0974, Introduced October 9, 2020.

[109] Elliot C. Williams, Returning Citizens Can’t Work In D.C.’s Medical Cannabis Industry. A New Bill Would Change That, DCist, October 14, 2020.

[110] Khadijah Tribble, Reckoning with Reparations: The Kush Economy is Our 40 Acres and a Mule, Kennedy School Review, June 4, 2018.

[111] Teo Armus, A Chicago suburb wants to give reparations to black residents. Its funding source? A tax on marijuana., The Washington Post, December 2, 2019.

[112] Enrique Lavin, N.J. Black leaders: Levy a cannabis tax to repair the harm done by the drug war | Opinion, NJ.com, November 30, 2020.

[113] Daniel Berti, Del. Lee Carter calls for Virginia to use marijuana taxes to fund reparations, Prince William Times, December 9, 2020.

[114] Council of the District of Columbia, Reparations Task Force Establishment Act of 2020 , B23-0968, Introduced October 5, 2020.

[115] Shaleen Title, Top 10 Equity Must-Haves in Any Legalization Bill , Commissioner Title, March 16, 2019.

[116] Jeffrey S. DeWitt, Fiscal Impact Statement – Safe Cannabis Sales Act of 2019, Office of the Chief Financial Officer, October 17, 2019.