DC’s education budget should provide traditional public schools and public charter schools with the resources they need to enable all students to meet academic performance standards and thrive. High-quality public education can boost the District’s long-term economic future and help students achieve their goals, including economic success. When a student graduates from high school college- and career-ready, they are on right side of the dividing line between people who have an opportunity to obtain economic security and people who will likely be exposed to jobs that are volatile and low paying.

Yet, for years District lawmakers have approved education budgets that fail to provide adequate resources to meet the needs of the 94,603 students that show up to school eager to learn every day.[1] The education budget appears to be built largely around spending constraints—how much revenues are rising and other priorities—rather than on what is really needed.

The consequences are clear:

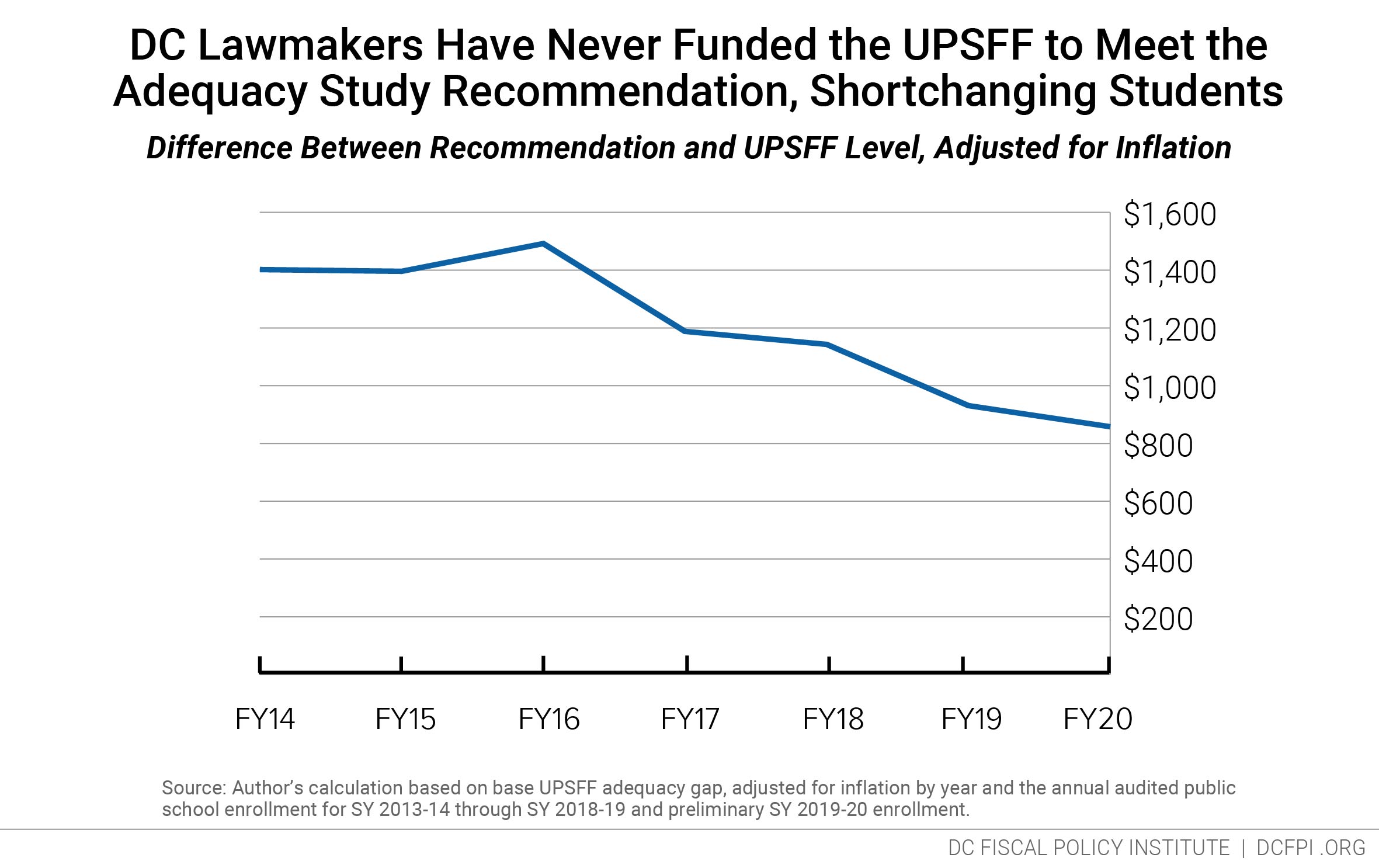

- The education budget is consistently below the recommended level in the DC Education Adequacy Study (Adequacy Study)—the cumulative gap over the past seven fiscal years is over $740 million dollars.[2],[3]

- The education budget has failed to grow in pace with rising personnel costs in two of the last three fiscal years.

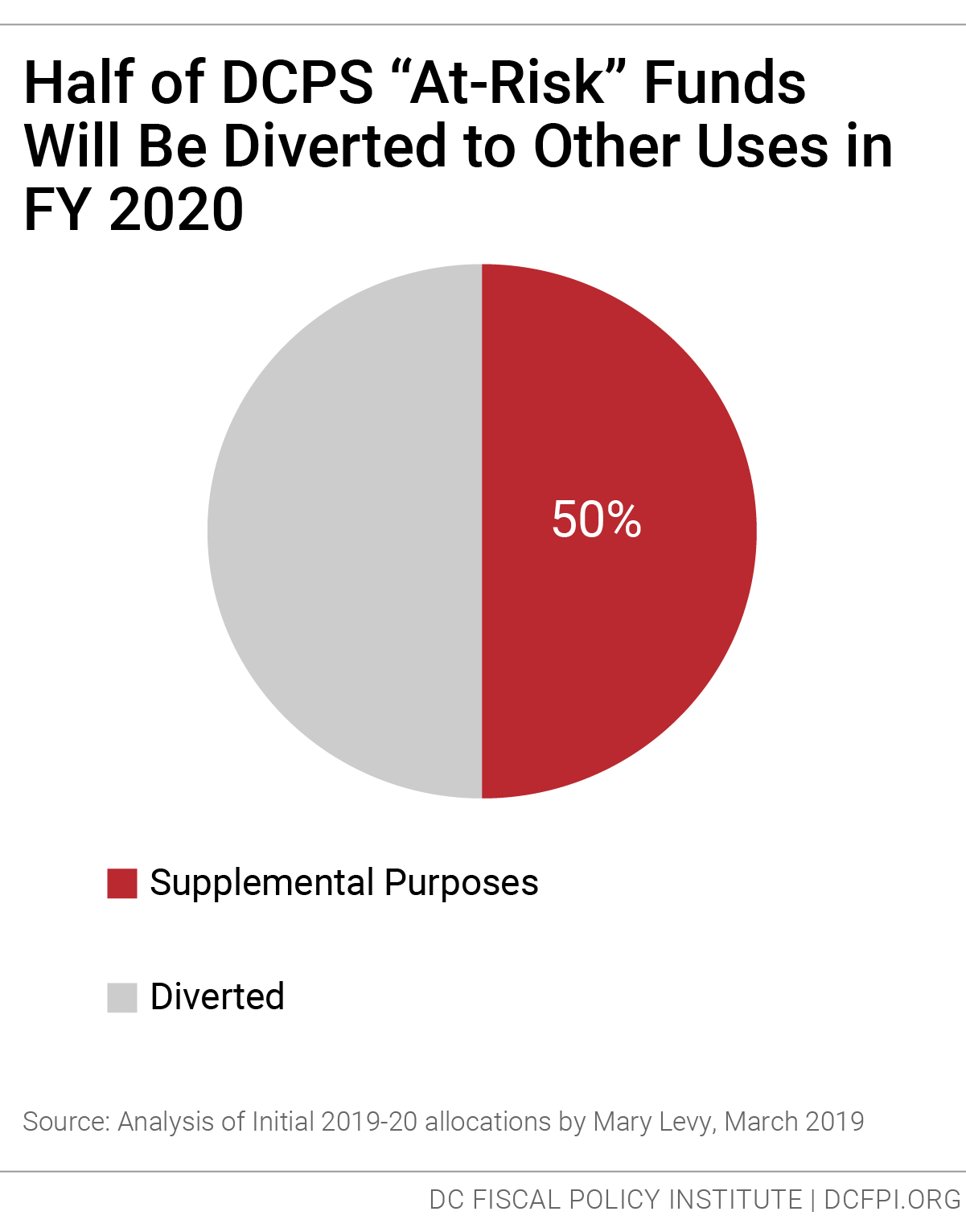

- District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) cannot fully fund its staffing model without supplanting funds intended for students who are considered “at-risk” of academic failure.[4],[5]

- Many schools in Wards 7 and 8 are facing budget cuts of five percent or more this year, a violation of DC Code.[6],[7]

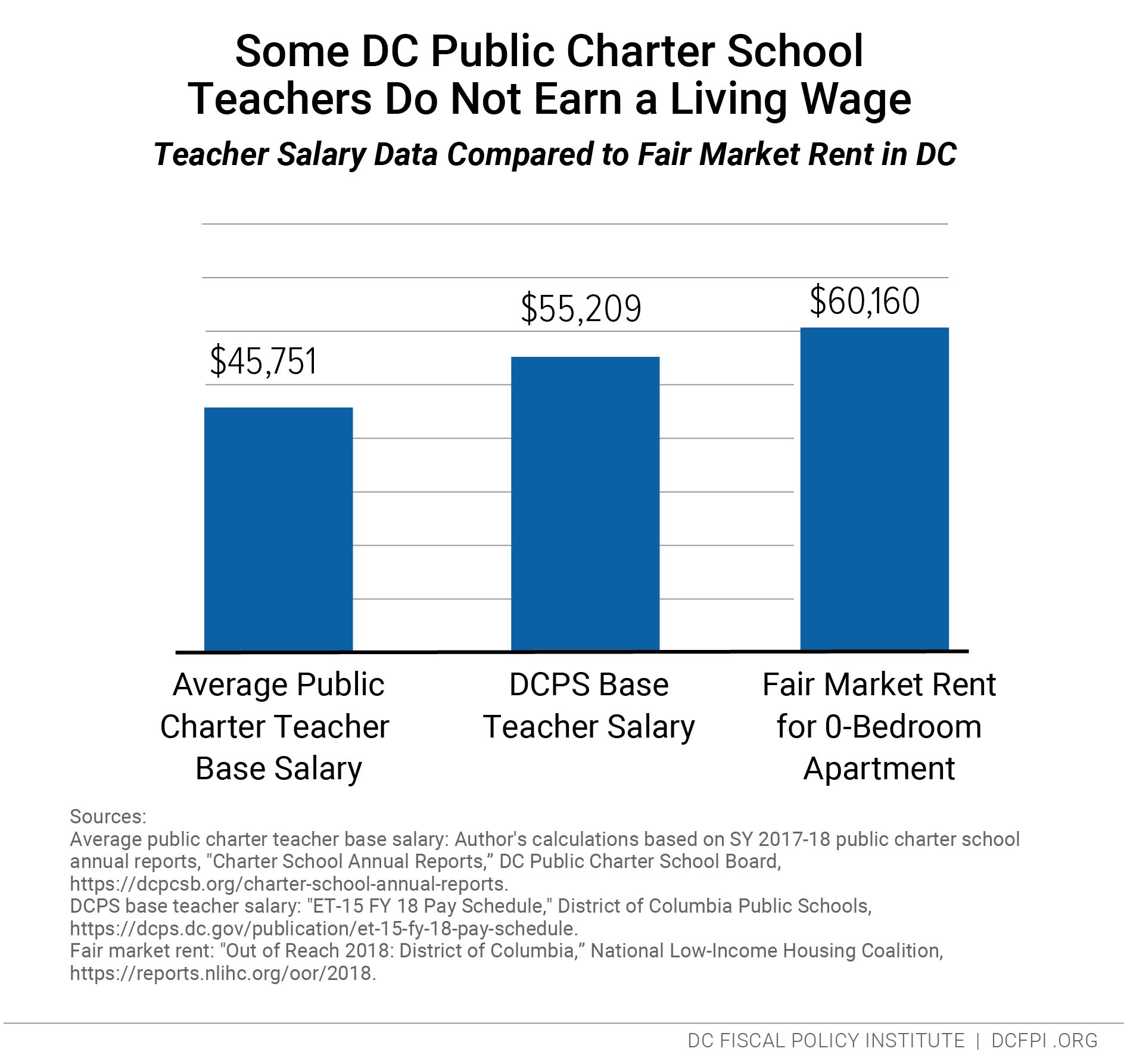

- Some public charter school teachers are not paid a living wage.[8]

- The District has not updated the Adequacy Study in over five years and has not taken yearly steps to estimate the true cost of education in the city.

Policymakers can, and should, build a better budget. The Mayor, the Deputy Mayor for Education (DME), DC Council, and DCPS have a role to play in securing an adequate education budget and distributing funds equitably.

In the short-term:

- The Mayor should tie the annual Uniform Per-Student Funding Formula (UPSFF) percent increases to rising personnel costs and inflation.

- The Mayor and DC Council should commit to a plan to close the seven percent gap between current funding and the recommendations of the Adequacy Study over the next two fiscal years, or by fiscal year (FY) 2022.

- The city should provide stabilization funds to DCPS schools with declining enrollment to maintain each school’s base funds at 95 percent of the previous year’s base funds.

- DCPS should establish internal controls to ensure at-risk funding is supplemental to each school’s base funding.

- The DC Council should amend the School Reform Act to establish a minimum living wage salary for public charter school teachers.

In the long-term:

- The Mayor and DC Council should ensure that UPSFF funding is equal to or greater than the outdated Adequacy Study recommendation adjusted for inflation plus any contractual increases to teacher compensation. When adjusting for inflation, policymakers should use the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation measure to project increased costs for non-personnel expenses and the Employment Cost Index (ECI) inflation measure to project increased costs for personnel expenses.

- The DME should reexamine the cost of providing an adequate public education every five years.

- DCPS should implement a staffing model, with fidelity, that ensures equitable programming at small and declining enrollment schools.

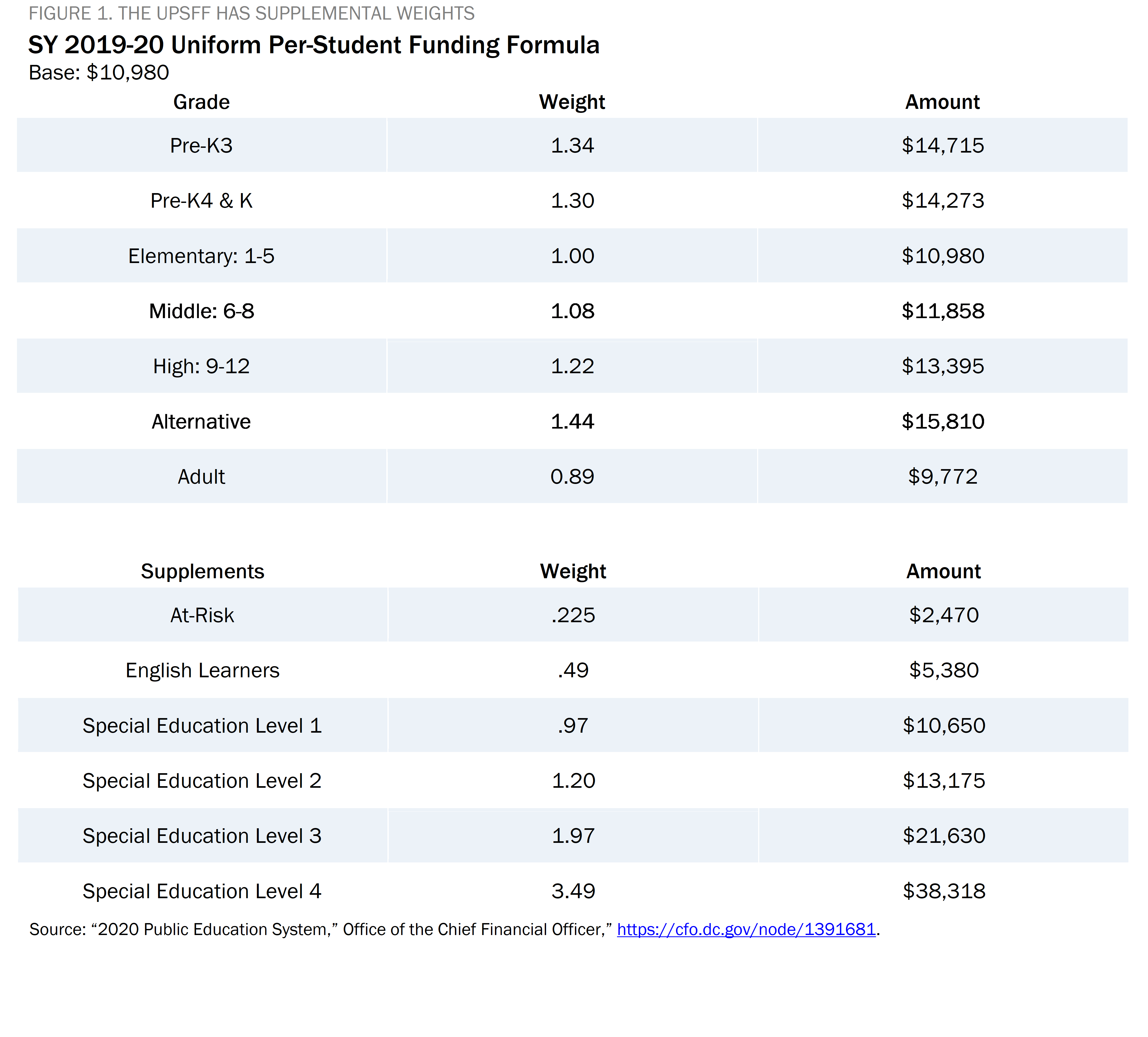

Background: School Budgets are Built on a Formula

The District allocates local revenue to DC public and public charter schools through the UPSFF. The formula starts with a foundation amount per student (or base). The foundation for school year (SY) 2019-20 is $10,980—with adjustments by grade level. The UPSFF for a three-year old prekindergarten student, for example, is 34 percent above the base foundation, reflecting the higher cost of smaller class sizes for DC’s youngest students. The UPSFF also has supplemental weights to reflect the added costs of serving students in special education, students considered “at-risk” of academic failure, and English Learners (Figure 1).[9],[10]

Total local funding for DCPS and each charter school Local Education Agency (LEA) is determined by multiplying the foundation level by the number of students by grade and multiplying the supplemental weights by the number of students in those groups. This means that getting the UPSFF right each year plays a critical role in supporting an adequate school budget.

Total local funding for DCPS and each charter school Local Education Agency (LEA) is determined by multiplying the foundation level by the number of students by grade and multiplying the supplemental weights by the number of students in those groups. This means that getting the UPSFF right each year plays a critical role in supporting an adequate school budget.

DC education officials, the Office of the Chief Financial Officer, the Mayor, DC Council, and local education experts designed the UPSFF in 1996. The group priced out a basket of goods to determine a foundation per-pupil cost of an adequate education (Figure 2).

While the costs associated with each of these expenses rises each year, the city does not recalculate the UPSFF each year based on updated prices for these factors. Instead, the Mayor proposes a percentage increase in the UPSFF using a variety of factors, including expected education cost increases and enrollment projections, but also non-education factors like the city’s expected revenues and spending priorities in other parts of the city’s budget.[11] Sometimes the Council further increases the UPSFF during the budget process. If District lawmakers don’t raise sufficient revenue or allocate adequate funds to cover rising education costs, LEAs must make difficult decisions to balance their budgets, such as hiring fewer staff, reducing programmatic offerings, or increasing class sizes.

While local funding makes up the vast majority of DC’s education operating budget, schools also receive federal funding, private funding, services, and personnel from other DC government agencies. For example, the DC Department of Transportation employs school crossing guards and the DC Department of Health provides nurses to some DC schools.[12], [13]

There are Several Key Cost Drivers for the Formula

The education budget makes up 28 percent of the District’s Local Fund budget in FY 2020, the largest single item.[18] Examining and accurately projecting the education budget’s key cost drivers are essential to adequately funding the District’s educational needs. Beyond cost increases due to enrollment changes, the budget should incorporate annual increases to the UPSFF driven by inflation, personnel (the most influential cost driver), and staffing model costs. In DC’s bifurcated public school system, both sectors have a unique set of cost drivers.

Inflation

Due to natural changes in the economy, costs grow over time, and it’s imperative the education budget keeps up. The standard measure of inflation that policymakers typically use to estimate inflationary increases to the District’s budget needs, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), measures changes in prices for a “market basket” of goods and services that reflect average consumption by the U.S. urban population as a whole. The Employment Cost Index (ECI), is a specific measure of changes in costs for compensating workers through wages and fringe benefits, such as health premiums and pensions.[19] ECI tends to grow faster than CPI in part because personnel expenses include health care costs, which are rising far faster than the cost of the market basket of goods.

Wages and benefits make up a significant share of education spending. This means that the largest share of the education budget is rising faster than standard inflation. Annual adjustments to the UPSFF should take into account that personnel costs grow with the ECI, while non-personnel costs grow with the CPI.

Personnel Costs in DCPS

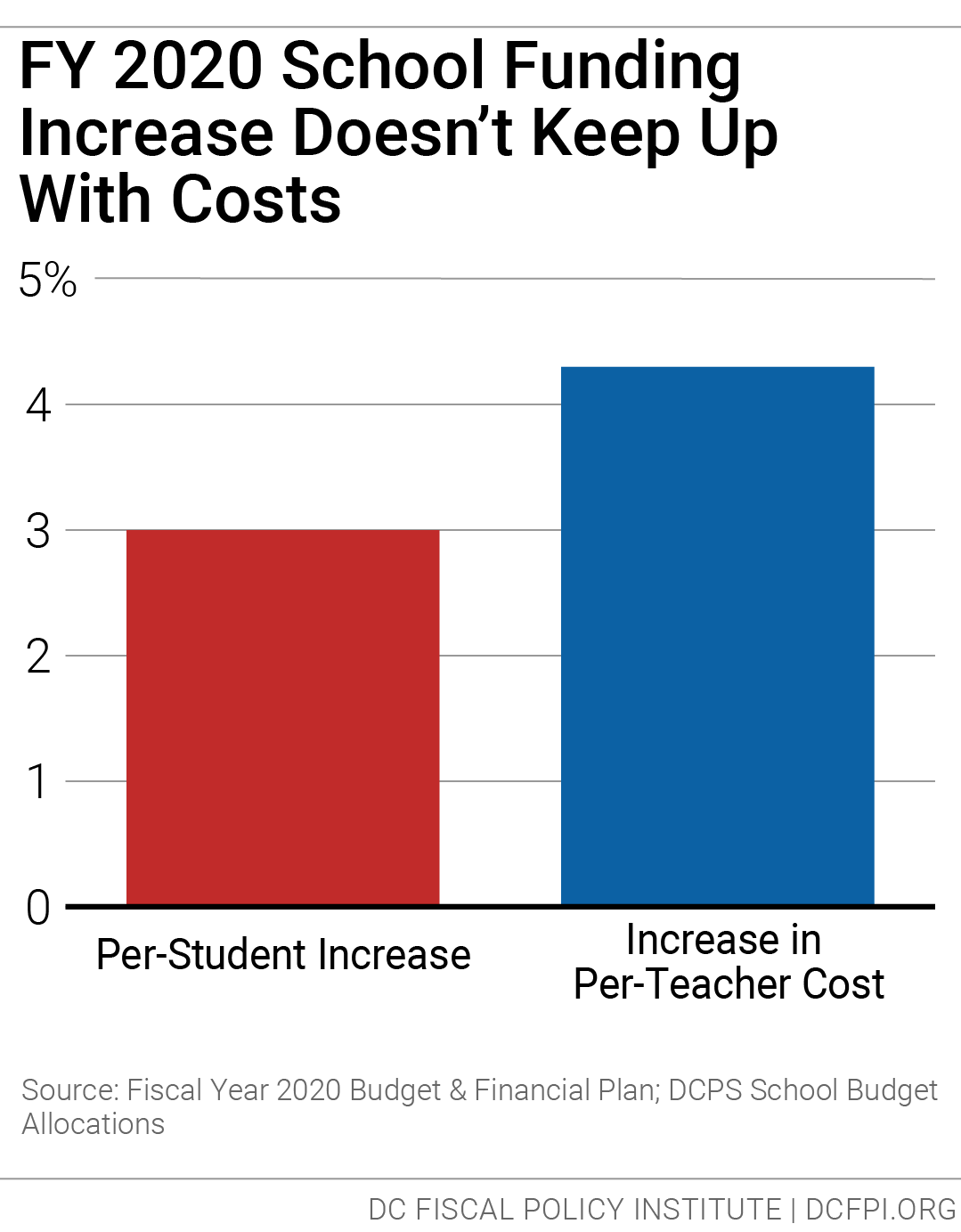

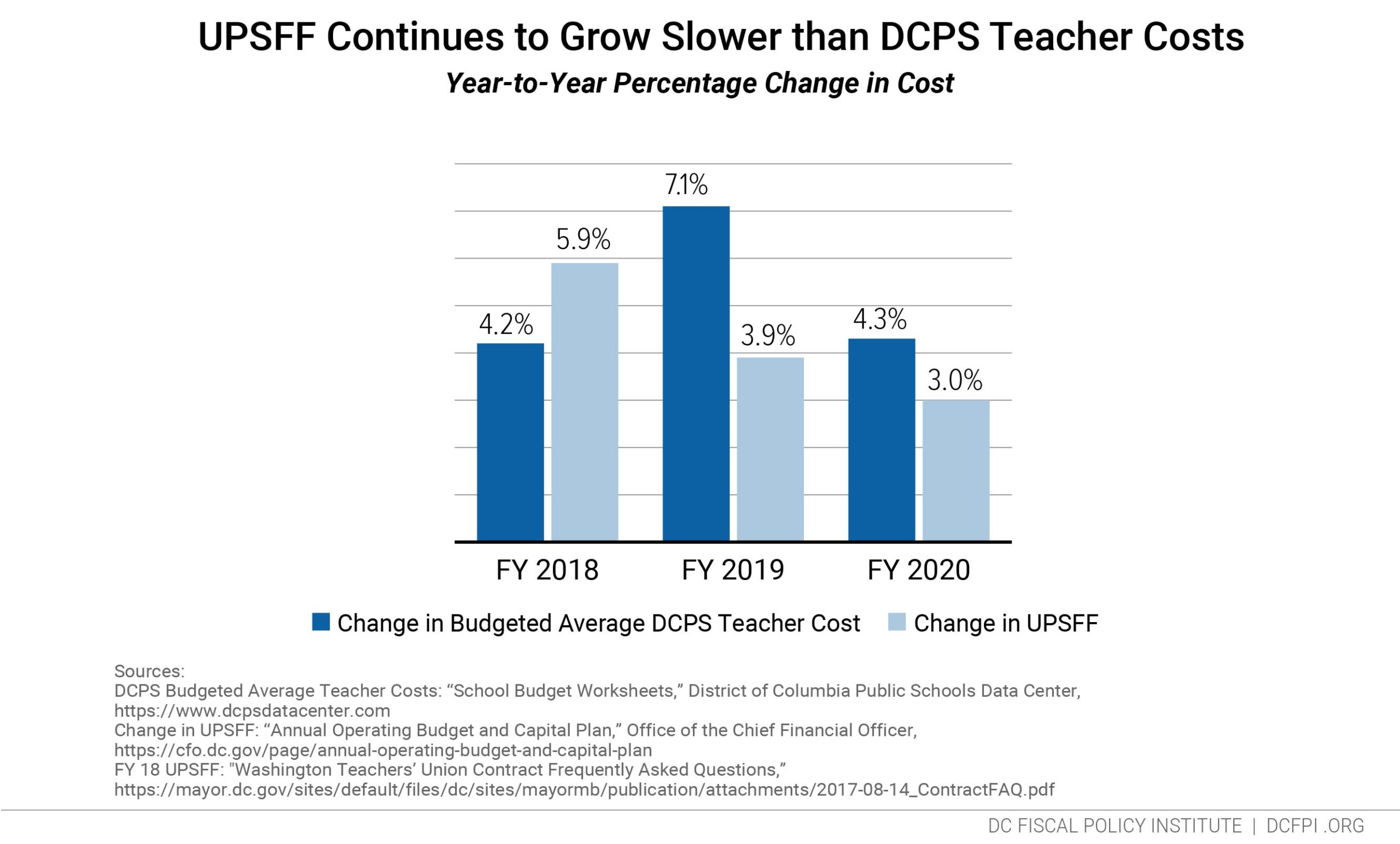

Factors that drive growth in DCPS personnel costs include inflation, contractual obligations with the Washington Teachers Union (WTU), and performance bonuses. In FY 2020, DCPS personnel costs are projected to rise by 4.3 percent while lawmakers only increased the UPSFF by 3 percent (Figure 3). This is the second time in three years that the UPSFF increase failed to keep up with rising teacher expenses (Figure 4).

When the UPSFF grows slower than personnel costs, schools face budget cuts. In recent years, these cuts disproportionally affected schools in low-income, Black neighborhoods.[20]

These figures actually understate the gap between recent funding increases and rising DCPS personnel costs. Greater retention of highly effective staff resulted in increased personnel expenses in SY 2018-19, because DCPS pays its teachers relative to their years of experience and awards annual $25,000 bonuses for effectiveness.[21] As a result, DCPS faced a $25 million budget shortfall. The school system instituted a hiring freeze at its central office and curtailed employee travel, but the Mayor still had to reprogram $10 million from other city agencies to balance the DCPS FY 2019 budget.[22] We should celebrate teacher retention and make the investments needed to keep effective teachers in the profession.

Going forward, budget officials should reevaluate the methods used to project personnel costs to help avoid future funding gaps. Rising personnel costs due to inflation, retention, and performance bonuses should inform the UPSFF on the front end, so the city does not have to scramble to balance its budget at the end of the fiscal year.

DCPS Staffing Model and Stabilization Law

It is more costly to educate students in small and declining enrollment schools than large schools because small schools cannot take advantage of some economies of scale that reduce the per-student costs of educational resources.[23] DCPS implemented the CSM in SY 2008-09 to ensure that every school, regardless of size, has certain resources needed for the school to operate, such as a librarian and an instructional coach. Students who are zoned to attend small or declining by-right neighborhood schools should have access to equitable and robust academic programming; the Mayor and DC Council should consider the commitment to programmatic equity at small DCPS schools as a cost driver for DCPS.

The law requires DCPS to provide stabilization funds to schools with declining enrollment to maintain each school’s budget at 95 percent of the previous year’s amount.[24] (DCPS did not follow this law in SY 2019-20, as described below.) However, stabilization is currently a flawed safeguard for school budget equity. Schools with an increased population of English Learners, students with disabilities, or students who are at-risk appear to have larger budgets due to supplementary UPSFF dollars. In order to implement stabilization meaningfully, DCPS should ensure no school loses five percent or more of its current funding from one year to the next using base funds only.

Public charter schools are not subject to stabilization laws. In recognition of DCPS’s unique obligation to operate by-right schools in all neighborhoods, DCPS should have access to stabilization funds outside of the UPSFF.

Personnel Costs in DC Public Charter Schools

Public charter LEAs have exclusive control over setting salaries, and the vast majority of teachers lack union protections. LEAs can choose how they invest their resources: some schools pay higher salaries and some invest in innovative programming, while others prioritize small class sizes or co-teaching.

The city’s education budget should not only keep up with inflation but also be sufficient to pay all public school teachers a living wage that supports professional growth. Yet, an inadequate UPSFF and the lack of labor protections mean that some charter school teachers do not make a living wage.[25] The average base pay for public charter school teachers—currently $45,751—is $15,000 below the $60,160 income needed just to afford a zero- bedroom apartment in DC in 2018 (Figure 5).

The District should amend the School Reform Act to require the charter sector to pay their school teachers a minimum salary that is tied to fair market rent for at least a zero-bedroom apartment, so that their salaries are sufficient to cover their basic needs.

School Funding Increases in DC Have Been Uneven and Damaging

Current Funding is Below Expert Recommendations

In 2013, the DME released a rigorous analysis of the costs of providing an educational program to support all students in meeting academic standards. The Adequacy Study took into consideration best practices for class sizes, staffing, teaching supports, and support for students with special needs.[26] The study recommended a base per-student funding level of $10,557, or $11,840 when adjusted for standard CPI inflation. The current FY 2020 base per-student allotment is $10,980—about $860, or seven percent—below the recommended level (Figure 6). This means that on a system-level, the base UPSFF falls short of what’s needed to provide a high-quality education by at least $80 million dollars.[27] Since FY 2014, DC students have lost out on over $740 million dollars that would have been included in the education budget if it kept up with the base recommendations of the Adequacy Study.[28]

This gap is even larger when increases in DCPS teacher costs are considered. In FY 2020, the average DCPS teacher costs about 20 percent more than it did in FY 2014, in part because of the 2016 negotiated contract that guarantees higher wages for teachers.[29] This compares with an inflation growth rate of 10 percent since FY 2014. Since personnel costs have grown faster than standard inflation, the seven percent adequacy gap is a low-end estimate of how DC’s education budget is inadequate. A more accurate estimate would both account for the higher compensation costs due contractual teacher salaries, but also growing costs in recurring personnel expenses using ECI and non-personnel expenses using CPI.

The Consequences of Inadequacy Harm Students and Teachers

Under an inadequate budget, DCPS is not complying with two budgeting laws intended to protect students who are at-risk or attend small or declining enrollment schools. First, several schools are a facing budget cuts of five percent or more, a violation of DC law. Second, DCPS is misusing about half of its at-risk funds to cover staffing that should be guaranteed by the CSM. In the public charter sector, some public charter school teachers do not earn a living wage. Until DC’s education budget is adequate, both school systems will continue to make inequitable decisions about teacher salaries, staffing models, and budget laws meant to provide additional funding to students who need it most.

Budget Cuts in Low-Income Neighborhoods

Inadequacy in the education budget has a disproportionate impact on students who attend schools in low-income, primarily Black neighborhoods. From FY 2019 to FY 2020, 19 schools faced budget cuts of five percent or higher, a violation of DC law.[30] Fifteen of the 19 schools are located in Ward 7 and 8, which have the highest percentages of child poverty in the District.[31] These budget cuts compound the systematic socioeconomic disadvantages east of the Anacostia River, particularly concentrated poverty, that are erecting hurdles to the community’s ability to access opportunity. Until DC has an adequate education budget, DCPS should prioritize stabilization funding so schools do not face further declining enrollment.

DCPS is Misusing At-Risk Funding

DCPS is misusing about half of the money meant for students considered at-risk of academic failure to make up for underfunding in the base formula (Figure 7). Students who are at-risk receive an additional allocation of $2,471 in FY 2020. DC Council requires DCPS to allocate at least 90 percent of at-risk funding towards school-level budgets at the schools where at-risk students are enrolled. DCPS’s at-risk funds must be supplemental to each school’s gross budget and not supplant any UPSFF, federal, or other funds to which the school is otherwise entitled.[32]

Yet, the Office of the DC Auditor found that DCPS misspends its at-risk funds to fund staffing positions at schools with at-risk students—positions that other schools receive under their base funding—rather than use the funds to supplement services.[33] The education budget should be adequate so DCPS can protect declining enrollment schools and allocate at-risk funds to at-risk students as intended by law.

In the public charter sector, LEAs are not held to the same “supplement, not supplant” laws for at-risk funds. Since most LEAs have few schools, at-risk funds in the charter sector largely follow the student, although each LEA has discretion over how to use the funds.

Unequal Philanthropic Support is Exacerbating School Inequities

An underfunded UPSFF leads schools to turn to philanthropy and parent organizations, leading to inequitable funding. The highest-performing DCPS and public charter schools spent more per-student than they received through the UPSFF, according to the Adequacy Study. The weighted per-pupil average with private funding in high-performing schools in SY 2011–12 was 23 percent higher than the per-pupil allocation without private funding.[34]

Today, DCPS students who attend by-right schools in wealthier neighborhoods are more likely to benefit from increased school funding through parent organizations. Some schools fundraise for full-time employees and extracurriculars that are out of reach for public school students as a whole through the UPSFF. These extra dollars are likely giving these children an academic edge, further exacerbating school inequities.

In the charter sector, the three-year average philanthropic grants and contributions per-pupil from FY 2016 to FY 2018 was $941, which ranges from $0 to $16,272 per student.[35]

In a public school system, public funding should be adequate and equitable so students in both sectors and in every neighborhood attend schools with sufficient resources and staffing.

Conclusion and Recommendations

DC’s education budget lacks the intentionality needed to fix systemic inequities. Yet, DC is a prosperous city and can take intentional steps to provide all students with an adequately funded education. The recommendations of this paper are common-sense reforms the Mayor, DC Council, DME, and DCPS can implement to get the education budget back on track.

In the short term:

- The Mayor should tie the annual UPSFF percent increases to rising personnel costs and inflation. At a minimum, the UPSFF should keep up with inflation and personnel costs. The current disconnect between rising costs and annual increases to the UPSFF leads to forced budget cuts that disproportionally impact low-income students attending by-right neighborhood schools in primarily Black neighborhoods.

- The Mayor and DC Council should commit to a plan to close the seven percent gap between current funding and the recommendations of the Adequacy Study over the next two fiscal years. The 2013 Adequacy Study is the first and only methodologically rigorous analysis of the costs of providing an adequate education for all DC students. Until this study is updated, the Mayor and DC Council should commit to a two-year plan to close the seven percent adequacy funding gap over the next two fiscal years.

- The city should create a special stabilization fund to ensure no DCPS school loses more than five percent of its previous year’s budget. Stabilization is required by law to protect DCPS students who attend by-right neighborhood schools with declining enrollment. In recognition of DCPS’s unique obligation to operate by-right schools in all neighborhoods, DCPS should have access to stabilization funds outside of the UPSFF. DCPS should calculate annual budget losses using only base funds, not the supplemental funds that are meant to provide additional targeted assistance to students who are at-risk, English Learners, or students with disabilities.

- DCPS should ensure at-risk funding is supplemental to each school’s base funding. By law, DCPS’ at-risk funding should not supplant other funding. DCPS should reform their school allocation method to ensure schools with higher percentages of at-risk students are not losing base funding they are entitled to under the CSM.

- DC Council should amend the School Reform Act to establish a minimum living-wage salary for public charter school teachers. All teachers should earn a living wage needed to live and afford basic needs in DC. Since public charter LEAs have exclusive control over personnel, legislation is needed to guarantee that public charter teachers earn a minimum salary that is at least equal to what is needed to afford a zero-bedroom apartment, per the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s fair market rent estimates.

In the long term:

- The Mayor and DC Council should ensure that UPSFF funding is equal to or greater than the Adequacy Study recommendation adjusted for inflation plus any contractual increases to teacher compensation. Policymakers should use the CPI inflation measure to project increased costs for non-personnel expenses and the ECI inflation measure to project increased costs for personnel expenses.

- The DME should reexamine the cost of providing an adequate education every five years. An updated adequacy study is needed to update the WTU salary scale and underlying best-practice research of the 2013 study.

- DCPS should implement a staffing model, with fidelity, that ensures equitable programming at small and declining enrollment schools. DCPS is in the process of reforming the CSM. The new model should retain the commitment to provide robust educational programming at all neighborhood by-right schools.

[1] Perry Stein, “D.C. charter schools experience first enrollment drop since 1996,” The Washington Post, October 22, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/dc-charter-schools-experience-first-enrollment-decline-since-1996/2019/10/22/95d691f6-f4da-11e9-a285-882a8e386a96_story.html.

[2] The Finance Project, Augenblick, Palich and Associates, “Cost of Student Achievement: Report of the DC Education Adequacy Study,” District of Columbia Deputy Mayor for Education, December 20, 2013, https://dme.dc.gov/page/dc-education-adequacy-study.

[3] Author’s calculation based on base UPSFF adequacy gap based on adjusted for inflation by year and the annual audited public school enrollment for SY 2013-14 through SY 2018-19 and preliminary SY 2019-20 enrollment.

[4] At-risk is defined as students who are homeless, in the DC foster care system, quality for TANF or SNAP, or high school students that are one year or more older than then expected age for their grade.

[5] Erin Roth and Will Perkins, “D.C. Schools Shortchange At-Risk Students,” June 26, 2019, Office of the District of Columbia Auditor, http://dcauditor.org/report/d-c-schools-shortchange-at-risk-students/.

[6] Ed Lazere, “Reversing School Budget Cuts in Ward 7 and 8 Should Be a Top Priority,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, April 29, 2019, https://www.dcfpi.org/all/reversing-school-budget-cuts-in-wards-7-and-8-should-be-a-top-priority/.

[7] DCPS Budget, D.C. Code §38-2907.01(2).

[8] Alyssa Noth, “Salary Transparency is Essential Step Towards Ensuring All Students Have an Effective Teacher” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, October, 9, 2019, https://www.dcfpi.org/all/salary-transparency-is-essential-step-towards-ensuring-all-students-have-an-effective-teacher/.

[9] “District of Columbia Public Schools,” FY20 Approved Budget and Operating Plan, Office of the Chief Financial Officer, Government of the District of Columbia, July 25, 2019. https://cfo.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ocfo/publication/attachments/ga_dcps_chapter_2020j.pdf

[10] An English Learner (EL) student is defined as a linguistically and culturally diverse (LCD) student who has an overall English Language Proficiency (ELP) level of 1-4 on the ACCESS for ELLs 2.0™ test administered each year.

[11] Letter from Deputy Mayor for Education Paul Kihn to DC Council Chairman Mendelson on Behalf of Mayor Muriel Bowser, “FY 2020 UPSFF Foundation Level Algorithm,” Office of the State Superintendent of Education, January 9, 2019, https://osse.dc.gov/publication/fy-2020-upsff-foundation-level-algorithm.

[12] “School Crossing Guard Program,” District Department of Transportation, https://ddot.dc.gov/page/school-crossing-guard-program.

[13] “School Health Services Program,” DC Health, https://dchealth.dc.gov/service/school-health-services-program.

[14]“Learn the Process & Analyze the Data,” District of Columbia Public Schools, https://www.dcpsdatacenter.com/budget_process.html.

[15] “Enrollment Audit Data,” Office of the State Superintendent of Education,” https://osse.dc.gov/enrollment.

[16] “Waitlist Data,” DC Public Charter School Board, April 16, 2019, https://dcpcsb.org/waitlist-data.

[17] “FY19 DCPS Comprehensive Staffing Model – HS,” District of Columbia Public Schools, October 22, 2018, https://dcps.dc.gov/publication/fy19-dcps-comprehensive-staffing-model-hs.

[18] Government of the District of Columbia, “FY 2020 Approved Budget and Financial Plan: A Fair Shot,” July 25, 2019, https://cfo.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ocfo/publication/attachments/DC_OCFO_Budget_Vol_1_0.pdf.

[19] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Cost Trends,” United States Department of Labor, https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ect/escalator.htm.

[20] Ed Lazere, “What’s in The Proposed Fiscal Year 2020 Budget for PK-12 Education?” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, April 3, 2019, https://www.dcfpi.org/all/whats-in-the-proposed-fiscal-year-2020-budget-for-prek-12-education/.

[21] “Compensation and Benefits for Teachers,” District of Columbia Public Schools, https://dcps.dc.gov/page/compensation-and-benefits-teachers.

[22] Perry Stein, “D.C. Public Schools Will Plug Budget Hole with Boost from Mayor’s Office,” September 27, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/dc-public-schools-will-plug-budget-hole-with-boost-from-Mayors-office/2019/09/27/fd1e138a-d990-11e9-a688-303693fb4b0b_story.html.

[23] The Finance Project, Augenblick, Palich and Associates.

[24] DCPS Budget, D.C. Code §38-2907.01(2).

[25] Alyssa Noth.

[26] The Finance Project, Augenblick, Palich and Associates.

[27] Author’s calculation based on approved base UPSFF for FY20 and initial enrollment projections for SY 2019-20.

[28] Author’s calculation is based on the base UPSFF adequacy gap adjusted for inflation in FY 2020 dollars multiplied by the annual audited public school enrollment for SY 2013-14 through SY 2018-19 and preliminary SY 2019-20 enrollment, excluding students the public school system serves students outside of the UPSFF. For years in which the number of students outside of the UPSFF was unknown, the author assumed the share was equivalent to the average share of non-UPSFF students from fiscal years FY 2017 through FY 2019.

[29] Author’s calculations based on DCPS per-teacher budgeted costs in Adequacy Study versus DCPS per-teacher budgeted costs for FY20.

[30] Ed Lazere, “What’s in the Approved Fiscal Year 2020 Budget for PreK-12 Education?” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, October 25, 2019, https://www.dcfpi.org/all/whats-in-the-approved-fiscal-year-2020-budget-for-prek-12-education/. DC Fiscal Policy Institute will update this toolkit when more data is available.

[31] “Child poverty by ward in the District of Columbia,” The Annie E. Casey Foundation Kids Count Data Center, https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/6748-child-poverty-by-ward#detailed/21/1856,1858-1859/false/870,573,869,36,868,867,133,11/any/13834.

[32] DCPS Budget, DC Code §38-2907.01(3).

[33] Erin Roth and Will Perkins.

[34] The Finance Project and Augenblick, Palaich and Associates.

[35] “Fiscal Year 2018 Financial Analysis Report,” DC Public Charter School Board, https://dcpcsb.egnyte.com/dl/qDfQOo8sSC/.