Mayor Bowser has proposed an expansion to a 20-year property tax break for commercial developers to convert their office space into housing downtown—reducing the required share of units set aside for affordable housing, exempting them from prioritizing DC workers in hiring as is required of all developers receiving public subsidies of this magnitude, and waiving tenant rights when buildings are sold. The expansion locks in a 600 percent increase to the size of the abatement in 2028 and could cost DC nearly $1 billion over the course of 20 years. DC Council should reject the loosened affordable housing requirements and proposed exemptions from worker protections and tenant rights and add safeguards that ensure responsible use of public dollars.

The Mayor proposed, and the DC Council passed with amendments, the “Tax Abatements for Housing in Downtown Act of 2022” in the fiscal year (FY) 2023 budget, creating the Housing in Downtown (HID) Abatement. The mayor’s current proposal to expand the HID Abatement—before the program has been fully designed, launched, or proven to work—creates a different set of rules for developers converting downtown commercial property to residential units by exempting them from DC’s First Source and Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) laws.

DC’s First Source law requires businesses receiving public subsidies to give first consideration for jobs to DC residents. Initially intended as a way to facilitate tenant purchase of residential properties, TOPA has become a critical way for tenants to negotiate for their own housing stability when their building owner decides to sell the property. At hearings in front of the Committee on Business and Economic Development and Committee of the Whole, commercial developers argued that lenders won’t finance residential conversions or rebuilds with these requirements in place. Yet, evidence from the residential development market points to the contrary. Investment capital has poured into the District for decades, funding the recent build out of both Navy Yard and NoMa. All housing units in those developments were subject to TOPA. The mayor’s proposal sets a dangerous precedent for eliminating requirements for receiving public subsidies for a small and powerful interest group. When DC government intervenes in the housing market, it should be to protect the public interest and not the profits of developers.

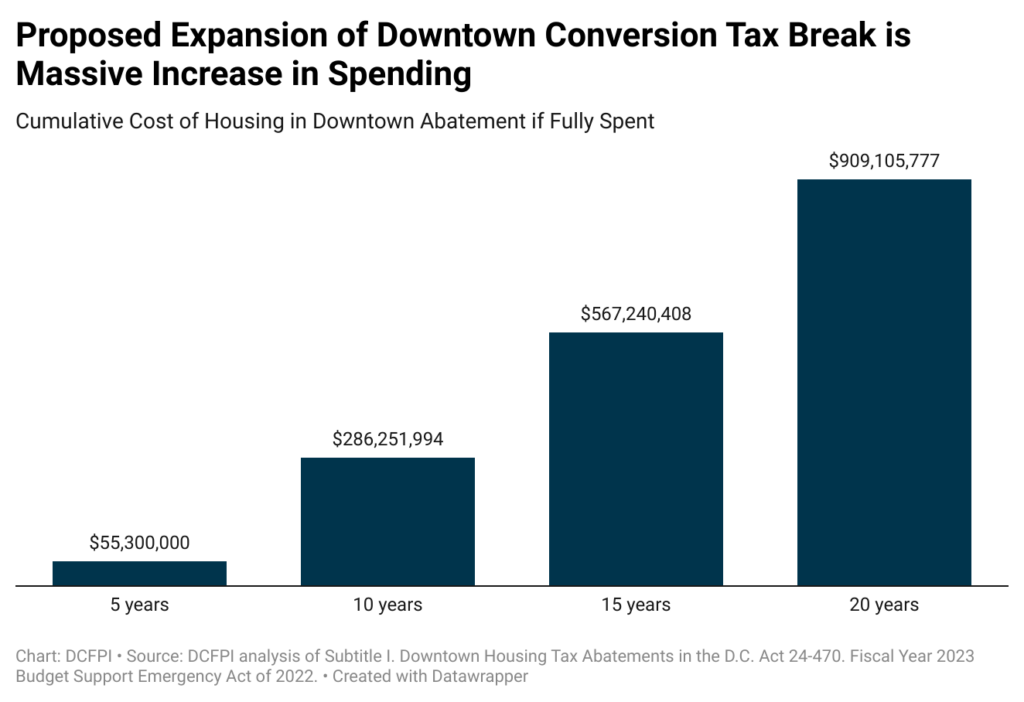

The mayor’s proposed expansion also increases the cap on the abatement by 600 percent in a year that falls outside the current four-year financial plan. This amounts to budget gimmick that locks in a high level of spending in a future year when we don’t yet know what the trade-offs would be. And cumulatively, it could cost DC nearly $1 billion 20 years from now. Research shows that tax abatements often go to companies that are already prepared to engage in the business activity the tax abatement is aimed at incentivizing, thereby wasting public funds. They are also often costly yet not highly correlated with unemployment or income levels, or with future economic growth. Many conversions have already happened without public subsidy. One analysis shows that DC led among cities in commercial to residential conversions between 2020 and 2021.

At the same time, the mayor has not demonstrated that building mostly market rate apartments will attract new residents to move to downtown DC. It takes more to create a thriving neighborhood, including access to amenities and public investment should focus on those that are broadly beneficial to residents. This could include free transit to downtown, subsidizing rents of micro businesses in buildings with major vacancies, adding parks and greenspaces, and hosting more events and festivals.

The property tax is one of DC’s largest revenue sources and most of the collections come from commercial, rather than residential, property. Yet, the mayor also has not demonstrated the revenue impact of shifting from commercial to residential property downtown. The former Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development reported to the Tax Revision Commission that they likely did not have analysis that “could get a positive FIS [fiscal impact statement] from the CFO’s [Chief Financial Officer’s] office…” He also notes that their in-house analysis assumes that brand new residents take up the new downtown units with no explanation of how or why this population growth would take place. That means that potential revenue recovery for DC counts on new income and sales taxpayers, a highly rosy assumption. No analysis has been shared to date offering the revenue impact of the conversions over the short, medium, or long-term and with evidence behind the assumptions.

DC Council should, at a minimum, reject the proposed costly increase to the abatement cap in FY 2028, and the elimination of key equity provisions like TOPA, First Source, and affordable housing requirements currently in place. Lawmakers should go further and add safeguards to any abatement program. That includes a so-called “clawback” provision that require developers to repay the District if they fail to comply with equity requirements or meet affordable housing targets. The program also should have an ending date. With a five-year sunset, the program would expire one year after the Office of the Chief Financial Officer publishes its next Tax Expenditure Report, which should document the effectiveness of the abatement at meeting its purported goals. The need for conversions is not permanent, neither should be the abatement. Council also should reduce the length of time that developers receive the abatement (20 years is too long) and phase down its value over time.

We all want a thriving downtown. But the Mayor’s proposal is tailor-made for developers—and it comes at the expense of DC residents and the District’s commitment to equity. At a time when the District has limited resources, our leaders should reject this costly giveaway and prioritize residents’ urgent needs in their spending decisions.