Everyone who wants to work should be able to find a job. While DC’s average unemployment of 4.6 percent in 2022 is down from 7.9 percent in 2020, the peak during the pandemic, the average unemployment rate masks extreme racial inequity.[1] A look at unemployment rates by race shows that Black workers in DC experience chronically higher levels of unemployment and are much more likely to be underemployed than white workers, and nearly half of unemployed Black workers experience it for long periods of time. These glaring racial disparities point to structural barriers to work for Black residents and call for focused policy interventions.

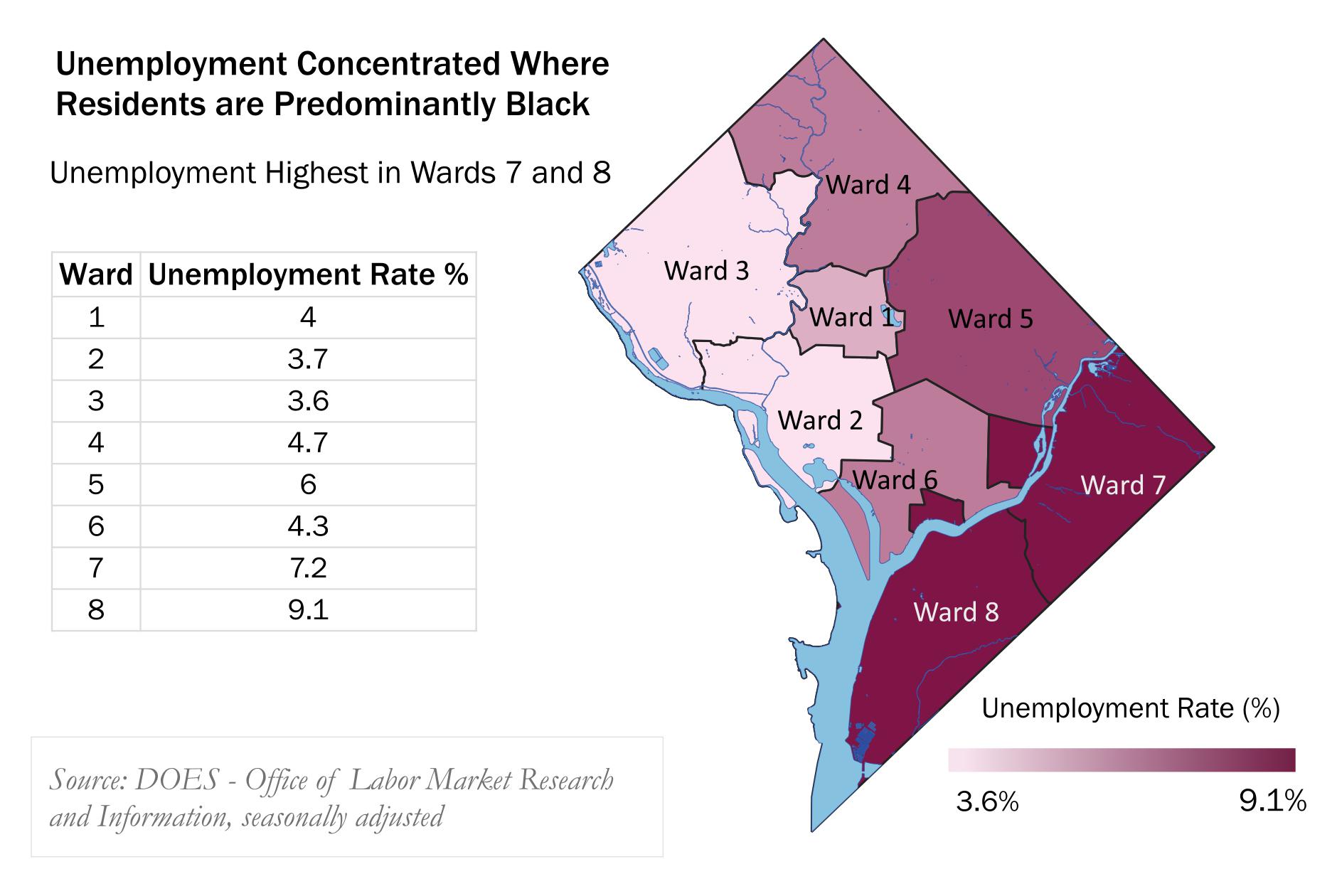

Black unemployment in DC is nearly 7 times higher than white unemployment and geographically concentrated. In 2022, average Black unemployment was 9.6 percent, compared to only 1.4 percent among DC’s white workers, a ratio of nearly 7 to 1, the worst in the nation. The District’s outsized Black-white unemployment gap cannot be attributed to differences in education or skills-training alone and reveals a deeply inequitable economy in which far too many Black residents are struggling to connect to work. Unemployment in DC is also geographically concentrated, following—and likely reinforcing—patterns of racial segregation. In May 2023, the unemployment rate in Wards 7 and 8 was 7.2 percent and 9.1 percent, respectively, Department of Employment Services (DOES) data show (Figure 1). By comparison, the unemployment rate in predominantly white Ward 3 was lowest at 3.6 percent.

Nearly half (47.7 percent) of all unemployed Black workers in 2022 were out of work for six months or more. (Sample sizes of white workers among the long-term unemployed are too small to report data.) Long-term unemployed workers are often stigmatized, making it harder to find employment, and research shows that long-term unemployment tends to result in lower future earnings, poorer health, and worse academic outcomes for the children of unemployed workers. Communities with a higher share of long-term unemployed workers may also experience higher rates of violence, resulting in ongoing trauma and harm.

Black workers are more than five times as likely to be underemployed than white workers (15 percent versus 2.7 percent). Underemployment measures the share of the labor force that is either unemployed, forced into part-time work because it is what is available, or “marginally attached” to the labor market, meaning people who want to and are available to work but have recently stopped job hunting for reasons including believing no jobs are available to them. These workers may face barriers to employment such as lack of child care or transportation, a chronic health condition, unstable housing, or having a criminal record. The proliferation of low-wage jobs that do not offer stable work hours or schedules may also contribute to underemployment.

Glaring inequities between Black and white workers are longstanding, across good and bad economic times. Between 2000 and 2022, annual average Black unemployment in DC never dipped below 8.3 percent and peaked at 19.4 percent in 2011. For white workers over that same period, the average unemployment rate is currently the lowest it’s been since at least 2000 at 1.4 percent and was never higher than 4.1 percent over that timeframe.

Recommendations for Supporting Black Workers

The District’s deep history of exploitation and discrimination against Black workers—including stolen labor when DC was a hub for slavery, restrictions of free Black workers to the lowest-paid jobs, federal government job discrimination through much of the 20th century, and exclusion of many Black workers from New Deal labor laws—led to present-day racial disparities in employment levels, occupations, wages, benefits, and opportunities to grow wealth. Transformative change is necessary to address the deep, longstanding structural issues that continue to harm Black workers. Policy solutions include:

- Continuing to provide economic supports for workers and families. To find and keep employment, workers need basic economic stability, which District leaders can support through food and housing assistance, cash supports, and the timely disbursement of Unemployment Insurance benefits. Emergency supports should be robustly funded while unemployment for Black workers and for workers in Wards 7 and 8 remains high. DC should also expand guaranteed income pilots into permanent programs and adopt a local Child Tax Credit not predicated on work. Providing people economic supports also increases worker power, by giving workers the economic cushion to leave an exploitative job or to say no to a job that doesn’t meet their needs and goals.

- Investing at scale in low-barrier employment and training programs. Earn-and-learn employment programs, such as transitional jobs, are a proven strategy for connecting jobseekers facing structural barriers to employment with immediate earned income, supportive services, and educational opportunities. DOES’ transitional jobs program is a good start, but only serves about 700 District residents each year. DC should also create a guaranteed jobs program that can facilitate meaningful connections to good jobs and circumvent racial bias and discrimination.

- Fully funding the Birth to Three Law and free buses. For many workers, child care and transportation are significant barriers to employment. Fully funding affordable child care for all families and investing in free public transportation are important steps for supporting workers.

- Funding and enforcing labor protections. The District has taken several steps to protect workers, including through paid family leave, paid sick leave, and the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights. However, more must be done to address ongoing barriers to employment. Black people continue to face discrimination in the labor market, including when it comes to hiring, salary, and job loss during economic downturns, as is documented by national research. Combatting racial discrimination in the labor market can include advancing policies to bolster organized labor and worker power, targeting enforcement toward lower-wage industries that are especially likely to violate existing laws, and ensuring employers are held accountable for workplace discrimination.

—

DCFPI’s research, analysis, and advocacy are made possible by our community of donors. By giving a gift today, you help sustain our work of advancing equitable policy, budget, and tax decisions.

[1] Except when otherwise cited, these and all other employment-related data come from an Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau.