People of color—longtime Black residents, immigrant families, and others—built this city and shaped its culture, and continue to make significant contributions to the economy. Yet decades of systemic barriers have denied them full opportunity, particularly Black residents, blocking them from homeownership, job opportunities, quality education, and health care.

The impacts are still evident today: in our affordable housing challenges that almost entirely fall on people of color, income disparities, distressing educational differences, and health outcomes. DC’s prosperity is not reaching many lower-income, Black long-time residents, and the rising cost of living means that many cannot afford to stay here.

The DC budget is a powerful tool to right these wrongs. Budgets have the power to help us create a future where all students have the resources they need to succeed, where no resident has to choose between paying rent and other necessities, and where all residents have access to quality, affordable health care.

Examining the latest DC budget through a racial equity lens allows us to see the budget in a different way, highlighting missing pieces that may not be evident otherwise. This lens can tell us who is—and isn’t—benefitting from the District’s current investments and identifies some steps the District can take towards a more equitable DC.

Education Equity Requires Increased Resources

The DC public education system is riddled with racial inequities, from a long history of legal school segregation and unjust funding by race.

A key to addressing these historical inequities is to intentionally provide more financial resources for students attending schools in areas of the District that traditionally faced divestment. Yet the school funding formula, which appears to treat all schools equally but relies heavily on enrollment, is leading to cuts at these schools. Enrollment declines are primarily occurring in low-income communities of color—often due to the rise in DCPS magnet schools and public charter schools—which means those neighborhood schools routinely face resource cuts.

Under the proposed budget, a number of DCPS schools faced budget cuts, nearly all of them in Wards 7 and 8; the funding added by the Council is not enough to eliminate these cuts. Budget cuts lead to cuts in staffing or services that can then lead to further enrollment declines. This outcome shows that the seemingly neutral allocation system is contributing to inequity and should be reconsidered.

For years, the District has not abided by requirements to devote more funds for low-income students and others at-risk of falling behind. DC’s per-student funding formula provides more resources for students who are at risk of academic failure, but the funding is 40 percent below the recommended level. Beyond that, DCPS knowingly diverts half of the “at-risk” funding to pay for core classroom staff, so that it’s not available for supplemental services as intended. Students in DCPS who are considered “at-risk” are consistently shortchanged.

Future school funding decisions should be rooted in equity. Treating everyone the same—what some call equality—ignores the need to focus on communities facing the greatest barriers. The process DCPS uses to allocate funds among its schools should focus on need, not simply on enrollment, and should not lead to deep cuts in schools that are predominantly Black and low-income. The District also should fully support at-risk funds and stop the practice of diverting these resources, to ensure they are getting to the intended students.

Housing Equity Requires Investments that Prioritize At-Risk Residents

The impact of DC’s gentrification is falling hardest on residents of color—including displacement of 20,000 Black residents since 2000—and is the direct result of decades of compounding housing policies that have been as advantageous for white households as they have been detrimental to Black households. These include restrictive deed covenants that barred Black residents from owning land, “urban renewal” projects that displaced Black businesses and residents, and systemic housing discrimination that has undervalued homes in majority-Black neighborhoods. As recently as the early 2000s, Black and Latinx residents were two to three times more likely to receive subprime loans than white residents.

This history has shaped today’s realities. Not only are white households far more likely to own homes compared to Black and Latinx households, the typical home value for Black homeowners is only two-thirds of the home value for white homeowners. Further, nearly 90 percent of the 27,000 extremely low-income households that spend at least half their income on housing are households of color and primarily Black.

The District has the resources to make sweeping investments in DC’s many affordable housing programs that benefit families who need it most and have been excluded from the District’s increasing prosperity. An equitable budget is one that takes bold steps to increase funding for DC’s crucial affordable housing programs to help build new housing, preserve the little affordable housing that’s left, and help more residents pay rent.

Health Equity Requires Eliminating Health Care Access Barriers

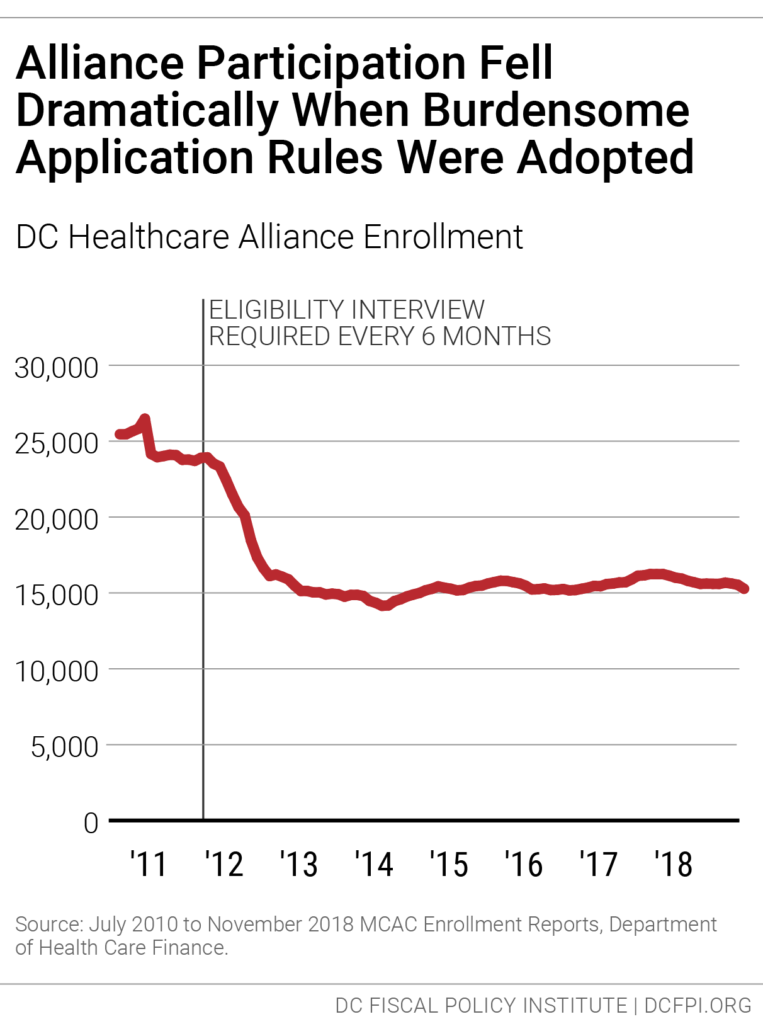

The DC Healthcare Alliance is a health care program that primarily serves immigrants. In 2011, DC implemented a new rule requiring participants to visit a DC social service center every six months to maintain their eligibility, rather than an annual recertification process that most DC benefit programs have. This is comparable to requiring all residents to visit the DMV in person every six months to keep a driver’s license. This stringent requirement led to a sharp drop in the number of residents getting health coverage through the Alliance.

The six-month recertification policy is a barrier imposed by the city that prevents individuals from accessing care. Because of the intensive recertification process, many Alliance participants face a lapse in coverage, meaning they have intermittent coverage and only return to the Alliance when they are in immediate need of medical care. The high rate of “churn” in the Alliance is a key reason the program’s cost to the city has increased sharply, even while people are losing coverage. The six-month recertification also contributes to long lines at DC’s social service centers, affecting all residents seeking assistance by creating backlogs and increasing the chance that applications aren’t processed.

The DC Council passed legislation to eliminate this unequal treatment in the Alliance and return to a 12-month recertification, but funding has not been provided to support the anticipated participation increase. The budget includes provisions to allow Alliance participants to renew their eligibility at a community health center, which will ease barriers on participants. However, truly budgeting for equity requires that the Council fully eliminate the six-month recertification requirement.

The DC Fiscal Policy Institute promotes budget and policy solutions to address DC’s economic and racial inequities and increase opportunities for residents to build a better future.