Updated on August 22, 2022 to reflect the changes OSSE made to the attestation requirement of the application process for pay supplements.

Every child deserves a strong start and a high-quality education, beginning at birth. Paying educators livable salaries is one step needed to boost teacher satisfaction, retention, and quality care, thereby improving DC’s early learning system. The DC Council recognized this and approved a modest income tax increase on the District’s highest income residents in part to finance substantial pay increases for approximately 3,000 early educators primarily caring for infants and toddlers through the creation of the Pay Equity Fund (PEF). The compensation program will disrupt the pervasive and centuries-long undervaluing of caregiving that has, due to structural racism and sexism, disproportionately harmed Black and brown women.

Educators are the foundation of DC’s early learning system, shaping the most formative years of infants and toddlers mental, emotional, and social development. Despite their important role, skills, and experience, early educators are currently paid a median annual wage of $36,337, just above minimum wage for full-time work.[1] The compensation program will bring early educators’ minimum salaries on par with DC Public School (DCPS) teachers’ minimum salaries and in line with their skills and credentials. DC’s Office of the State Superintendent (OSSE) will disburse the pay increases in two phases, beginning with two rounds of supplemental payments worth up to $14,000 each starting in late summer 2022, followed by a salary increase beginning October 2023. This ensures that the income boost reaches educators’ pockets this year, while DC officials have time to finish designing and implementing the permanent compensation program.

Policymakers also established an Early Childhood Educator Task Force comprised of early childhood education stakeholders, including providers, educators, advocates, and policy experts, to submit recommendations on the design of the compensation program to the Mayor and the DC Council.[2] This summer, the DC Council incorporated some of the Task Force’s recommendations into the fiscal year (FY) 2023 budget while giving OSSE some discretion to design and implement programmatic components. If well implemented, the compensation program will improve the economic security of early educators, 75 percent of whom are Black and brown women, increasing gender and racial equity, and likely boosting early education outcomes for infants and toddlers in the District.[3] In order to ensure a racially equitable program design and implementation process from start to finish, OSSE and lawmakers should:

- Adopt a Just Application Process. The application for the pay supplements includes a requirement that early educators “attest” to their understanding that OSSE wants them to stay in their job through December after receipt of the first pay supplement, which is intended to compensate them for work they have largely already done in FY 2022. This approach is likely to cause confusion.

- Protect and strengthen the District’s subsidy program. OSSE should give greater weight to subsidy participation in the equity adjustment to better protect access to high-quality care for families with low incomes. District leaders should monitor the effect that the compensation program has on providers’ participation in the subsidy program, if any, and adjust the equity adjustment as needed to strengthen and protect subsidies for children from families with low incomes.

- Aim for full parity. To fulfill the promise made in the Birth-to-Three for All DC Act (See below), the FY 2024 roll-out of the compensation program should, at minimum, include a comparable salary scale to DCPS teachers and health care benefits. District leaders should then work towards incorporating the remaining fringe benefits into the program and create minimum salaries for all early care staff, including the administrators, food service workers, and program directors left out of the program.

- Listen to community input. OSSE should establish a dedicated, accessible, regular forum for stakeholder engagement regarding the design and implementation of compensation program, as recommended by the Task Force. This would better ensure educators, parents, and providers can influence the design of the permanent program.

Early Educator Pay is a Racial Justice Issue

Higher pay is a key element of repairing the racist harm embedded in the child care and early education system. Although the work of teaching and caring for young children is highly skilled and complex, early education is one of the most underpaid sectors in the District. The historical undervaluing of the early education workforce has deep roots in white supremacist ideology and sexism.

American laws forced enslaved Black women to raise white children, and thereafter paid domestic service became seen widely as a gender-appropriate role for freed Black women and later brown and immigrant women.[4] Prior to and after emancipation, DC enacted legal restrictions that exploited Black workers through forced unpaid and underpaid labor, such as Black Codes. These codes played a key role in largely limiting Black women to domestic service and ensuring Black labor was cheap.[5] Some of America’s Black Codes mandated Black people to sign labor contracts or else face jail and be hired out to white landowners.[6]

Institutions also geared educational opportunities towards domestic service work for Black women.[7] By 1900, about 90 percent of Black women workers in the District worked in domestic service.[8] The New Deal era cemented the exploitation of Black and brown women’s labor as federal lawmakers repeatedly left domestic workers—such as nannies and farm laborers—out of the laws that provided legal protections and benefits to other categories of workers, including the Social Security Act. Occupational segregation has persisted over decades, and regardless of education, skill, or experience, participation in highly feminized work—where Black and brown women have been overrepresented—comes with a wage penalty.[9]

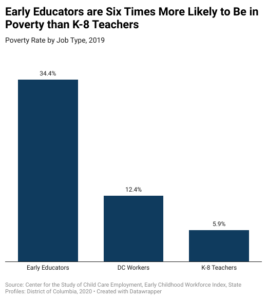

Low pay is also a result of decades of government underinvestment and a market-based system that operates on tight margins, due to a large dependence on parent fees and high fixed costs associated with low child-to-teacher ratios.[10] This situation is especially dire for infant and toddler care, where costs are the highest in the sector. Educators in DC with a bachelor’s degree take a 33 percent pay penalty if they choose to work with young children, rather than older children in elementary schools.[11] And this disparity is especially harmful to Black and brown educators, as they are more likely to work with infants and toddlers than white educators nationally.[12] And, at a rate of 34.4 percent, early educators in DC are nearly six times more likely to be in poverty than K-8 teachers (Figure 1).[13]

Low wages also make it harder for child care providers to attract workers with deep knowledge and experience in early childhood development, and it fuels high turnover and teacher shortages.[14] Early educators’ financial insecurity often leads to stress and anxiety, which can have adverse effects on the young children in their care.[15] On the other hand, higher wages for educators are correlated with better-quality education for young children. Wages are the most important predictor of quality among the adult work environment variables assessed, even after controlling for teacher education, training, and experience, according to a rigorous, multi-state study.[16] Children growing up in families with low incomes particularly benefit from high-quality early care and education programs. These programs can alleviate the disadvantages of poverty that disproportionately harm Black and brown children—such as stressors that stifle cognitive development—and increase the odds of entering school ready to learn.[17]

By raising teacher pay and setting salary minimums, DC invests in Black and brown women and children and repairs some of the harm of past policies and continued occupational segregation. The change also will help increase the supply of child care by creating more attractive working conditions and better position DC to provide quality care for all children who need it.

Pay Supplements Will Boost Early Educators’ Economic Security

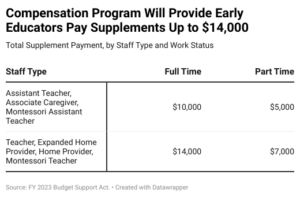

In phase one of the District’s early education compensation program, OSSE will distribute two pay supplements ranging from $5,000 to $14,000 each to early educators, depending on position type and full-time status, who work in classrooms up to age five in both center and home-based settings (Table 1). Teachers, assistant teachers, and home providers and caregivers employed by licensed child development facilities (CDFs) are eligible for the payments. They must directly apply for the supplements with OSSE’s third-party distributor AidKit. The compensation program will not reach all early learning staff, such as administrators, program directors, and food services staff.

Lawmakers first approved funding for pay supplements in the FY 2022 budget last year. OSSE will disburse the first supplement in one payment beginning in late summer 2022 to compensate workers for their labor during FY 2022, from October 2021 to September 2022.[18] OSSE is expected to soon release a schedule for the second supplement for FY 2023 for work performed October 2022 to September 2023.

The pay supplements will boost educator’s economic security. For full-time early educators earning the median wage of $36,337, $10,000 and $14,000 supplemental payments will increase wages by almost 30 percent and 40 percent, respectively. That equates to approximately $800 to $1,170, respectively, per month. And, $1,170 could cover approximately 70 percent of rental costs for a modest two-bedroom apartment in DC.[19]

One potential complication of the pay supplement remains to be fully addressed. Due to woefully low wages, some early educators access public benefit programs to help meet basic needs and provide for their children.[20] The extra income from the pay supplements could cause some workers who are currently receiving public assistance to see reduced benefits or be cut off from supports. To address these “benefit cliffs,” the DC Council’s budget bars public officials from counting the pay supplement towards income eligibility limits for locally-funded assistance programs.[21] The law also excludes the supplements from DC’s definition of gross income, meaning the pay supplement will not be subject to DC income taxes either.[22]

However, the pay supplement may affect eligibility and assistance levels for federally-funded public benefits, such as SNAP food assistance and Medicaid, under which recurring payments would be considered regular income. OSSE will disburse the first supplement in one payment in order to protect early educators’ from losing public assistance programs in the immediate term. It is likely, however, that OSSE will pay the second supplement in multiple payments over the course of FY 2023. It is crucial for OSSE and DC government leaders to resource outreach and technical support for early learning professionals in navigating potential disruptions to public benefits they may experience, as the Task Force recommended in its final report.[23]

Pay Supplement Application Process Could Limit Reach and Cause Confusion

In early drafts of the application for the initial pay supplement, and informational materials online, OSSE included a requirement that early educators self-certify their intention to stay in the early learning field at a licensed CDF until the end of December 2022.[24] That is three months after the end of the 2022 fiscal year (October 2021 – September 2022), which is the period that the funding for the first pay supplement is meant to cover. Refusal to self-certify disqualifies educators from accessing the funds, even though the law does not require educators to stay in the field. In days leading up to the program launch, OSSE relaxed the attestation to require educators to acknowledge that OSSE’s intent is for individuals to work through December, rather attesting that the individuals will indeed stay through December. OSSE’s approach will cause confusion about what is legally required, and it could deter some educators from applying for the pay supplement and/or making the best employment choices for their households.

While the required commitment is for just three months beyond the period covered by the supplement, it begs the question of how early educators will be treated in the permanent compensation program. Black women have endured centuries of forced or coerced labor in America, due to white supremacist beliefs of Black women’s inferiority, inherent laziness, or need for paternalistic rules to compel them to work. These beliefs have shaped policies and practices throughout this country’s history. A primary example is the TANF cash assistance program. TANF coerces women’s labor by imposing various sanctions and punishments around cash supports for not meeting specific work requirements, even if work is not best for families and their children at that time.[25] Lawmakers leveraged centuries-old racist stereotypes of Black women as undeserving of public assistance—such as the false narrative of indulgent “welfare queens”—to make harsh restrictions to cash and other supports more palatable to white Americans.[26] To great success, states use these punishments and unfair application processes to reduce TANF’s reach,[27] particularly in states with high concentrations of Black families.[28]

“Higher pay is a key element of repairing the racist harm embedded in the child care and early education system.”

OSSE’s required self-certification is meant to assure that early educators won’t leave after accepting the payment, but that payment covers work largely already performed and, beyond anecdotes, no evidence has been presented that supports the fear that workers will exit the field after receiving payment. To the contrary, these early educators are set to see substantial permanent pay raises next year, giving them a great incentive to stay on the job and in their field of work. This required attestation is unnecessary and unfair to ask of an undervalued, undercompensated workforce, three quarters of which is comprised of Black and brown women who have historically faced various forms of coerced labor.[29] The intent of the pay supplements is to reward educators for work they have already completed, not to compel them to remain in their field. OSSE should strip this “attestation” question from the application process and refrain from including such unfair and racially biased requirements in the permanent compensation program.

Long-Term Compensation Program Provides for Higher Salary Floors

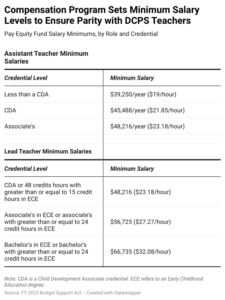

In phase two of the District’s early education compensation program, OSSE will distribute operating funding to CDFs, which will directly provide early educators’ pay raises beginning October 2023. In the FY 2023 budget, the DC Council adopted some of the Task Force’s recommendations for this component of the compensation program, including specific minimum salary levels differentiated by role and credentials that participating CDFs must pay (Table 2). These salary minimums put early educators’ minimum pay on par with DCPS teachers’ minimum pay, as envisioned by the Birth to Three for All DC Act. OSSE is required to update the minimums each year so that it maintains parity with teachers’ pay and for inflation (up to 3 percent), as funding allows.[30]

The compensation program is available to early educators in qualifying positions, like teachers and assistant teachers, who work in classrooms up to age five in both center and home-based settings. The minimum salaries will range from $39,250 for an assistant teacher with less than a Child Development Associate (CDA) credential to $66,735 for a teacher with a bachelor’s degree or higher. That highest minimum salary for teachers is nearly double the current median wage for educators, illustrating how lifechanging this program will be for those who educate young children.

This model provides stability to educators who will be able to rely on increased wages and programs that will be able to plan their budgets sustainably to meet wage expectations and ensure program quality.

By next March, the FY 2023 budget directs OSSE to create a payroll formula—informed by salary minimums, average workforce experience, and an equity adjustment—to disburse the compensation funding to participating CDFs.[31] CDFs must apply for these operating funds and meet the eligibility requirements that OSSE mandates, including entering into a contract and agreeing to pay the minimum salaries. The budget also directs OSSE to create a recommended salary scale that goes beyond minimum salaries to include pay bands or steps that reflect salary increases based on experience or time-in-position. The law does not mandate CDFs to pay beyond the minimums, but the salary scale would offer them information on what pay parity looks like with more experienced teachers. This design accounts for the reality that CDFs, unlike the uniform DCPS system, act as individual businesses and set their own salaries and policies on teacher titles and duties.

Equity Adjustment Should Incentivize Participation in the Subsidy Program

All licensed providers are eligible for the compensation program, but they are not all on equal financial footing due to widely varying tuition revenues and differences in quality ratings and business models, such as being in a center or home-based setting. The FY 2023 budget directs OSSE to develop an “equity adjustment” in the payroll formula to direct more funds to CDFs serving families and communities with fewer economic resources.[32] Providers predominantly serving families whose ability to pay is lower or those operating at a smaller scale need more funding to offer pay parity and high-quality care because they face ongoing and historic inequities that force them to operate on tighter margins and cause supply shortages.

For example, providers serving communities facing residential segregation and concentrated levels of poverty —particularly Black and brown families in Wards 7 and 8—rely more on support from the District’s child care subsidy program.[33] Families with low incomes are eligible for vouchers that they can use at licensed providers, but the reimbursement rates providers receive from OSSE have historically been insufficient to cover the cost of everything that goes into providing high-quality care.[34] This includes fair pay for a skilled workforce, rent on valuable ground floor levels, licensing requirements, utility bills, nutritious food, supplies like diapers and toys, and more. Because providers can only charge what families can afford, they cannot rely on parent fees in their economically segregated areas to pull them above water or contribute more to higher pay for educators.

Boosting the supply of child care for children in families with low incomes is also crucial, given about three in ten of them lived in child care deserts before the pandemic, or areas without enough licensed providers.[35] The pandemic caused 41 facilities in DC to permanently close,[36] and point-in-time data on the subsidy utilization rate in infant and toddler programs (or the number of children using subsidies compared to the number of licensed slots) has plummeted, particularly in areas with higher needs for affordable child care.[37]

If well-designed, the equity adjustment can be a reparative measure to offset this historic harm, better support providers operating on tight margins, and to increase the supply of high-quality slots for DC’s most vulnerable children. The Task Force suggested that part of the adjustment be based on the share of enrolled children using child care subsidies within a CDF, given the critical support they offer families with low incomes. Giving more value to subsidy participation in the adjustment would incentivize more providers to enroll in the subsidy program and/or serve more eligible students. For a provider that can recoup the full cost of care through parent tuition and base compensation funding alone, there is less of an incentive to participate in the subsidy program, further limiting choice for families struggling to make ends meet. This is in part due to the extra steps involved in the subsidy program aimed at ensuring high-quality care for children with low incomes and other logistics—such as requirements for the provider approval process, payment policies on attendance, and payment amounts.

Protecting and strengthening the subsidy program is critical to any racially just early education system. Expanding access to reliable, high-quality services through sustained investments will offer parents struggling on low incomes the support they need to work and gain greater economic security for their families. OSSE should follow the Task Force’s recommendation to give higher weight to providers participating in the subsidy program, and they should test the adjustment against real scenarios and refine it over time to ensure the program is meeting its intended equity goals.

Health Care Benefits Are Yet to be Guaranteed

The Birth-to-Three Act’s vision and mandate for compensation is broader than pay increases. It includes fringe benefits that DCPS teachers receive, such as health care, paid time off, and retirement. Whereas DCPS provides health care and other benefits directly and uniformly to teachers, some early education providers cannot afford to provide these benefits to their employees. To move towards this vision, the DC Council put into the FY 2023 budget the option for OSSE to partner with DC Health Benefit Exchange and use any excess PEF funds (i.e., money available after the pay increases) to subsidize health care benefits to early educators.

While it is promising that the DC Council established health benefits as an allowable use in the PEF, excess funding is not guaranteed. Health insurance is essential to improving physical and mental health outcomes, and it reduces the chance that a family will face severe financial hardship when a medical emergency hits. Currently, early educators access health care in a variety of ways, including employer-provided insurance, Medicaid, or subsidized insurance through the marketplace. It is also likely that some early educators don’t have health insurance because they can’t afford it.

Some workers could be worse off if their wage increase fails to outstrip any associated increase in health care coverage cost. Higher costs could be a result of losing Medicaid eligibility or facing a higher premium through employer-sponsored insurance or through the marketplace. The minimum salary levels for all assistant teachers ($39,500) and lead teachers ($48,200) are higher than the Medicaid income threshold for single workers without children ($27,000) and single workers with one child ($37,700); other workers could also lose eligibility depending on their family size and credentials.

OSSE should work with the DC Health Benefit Exchange to collect information on health insurance needs among early educators and explore ways to address any threat to their coverage, such as providing early educators a subsidy they can use to afford health care through the District’s subsidized marketplace. As they develop a strategy for providing health insurance benefits, OSSE should keep lawmakers informed of whether excess PEF funding is adequate to cover health program costs.

OSSE Should Listen to Community Input

Policy processes that incorporate the key stakeholders, such as early educators, communities of color, providers, and parents can better position the District to build a racially just compensation program. OSSE should establish a dedicated, accessible, regular forum for intentional stakeholder engagement regarding the design and implementation of the long-term compensation program, as recommended by the Task Force. This would better ensure key stakeholders, including those who have been historically excluded from of the decision-making process, can influence the design of the permanent program—including the equity adjustment, full salary scale at parity, health care plan, and potential expansion of the program to other CDF workers such as directors and food service staff. These stakeholders and their experiences should also help refine the program’s design as needed, down the road.

This report is supported by grants from Children’s Equity Fund; the Greater Washington Workforce Development Collaborative, a project of the Greater Washington Community Foundation; Washington Area Women’s Foundation’s Early Care and Education Funders Collaborative; EARN Worker-Centered Priorities for an Equitable Recovery Fund, a project of EPI and the Economic Analysis and Research Network (EARN); and others.

[1] Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2021 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates for District of Columbia.

[2] Final Report of the Early Childhood Educator Equitable Compensation Task Force, Submitted to the Mayor and Council of the District of Columbia, March 23, 2022.

[3] Due to data limitations, this study did not include preschool teachers working in elementary schools in its analysis. See Table 8. Julia Isaacs et. al, “Early Childhood Educator Compensation in the Washington Region,” the Urban Institute, April 2018.

[4] Julie Vogtman, Undervaluled: A Brief History of Women’s Care Work and Child Care Policy in the United States, National Women’s Law Center, 2017.

[5] Doni Crawford and Kamolika Das, Black Workers Matter: How the District’s History of Exploitation and Discrimination Continues to Harm Black Workers, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, 2020.

[6] Nadra Kareem Nittle, How the Black Codes Limited African American Progress After the Civil War, History Stories, 2021.

[7] Julie Vogtman (2017). For the original research, see: Claudia Goldin, Female Labor Force Participation: The Origin of Black and White Differences, 1870 and 1880, 37 J. econ. Hist. 87 (1977)

[8] Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital (The University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

[9] Julie Vogtman (2017).

[10] Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, Early Childhood Workforce Index 2020: Early Educator Pay & Economic Insecurity Across the States, 2020.

[11] Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, Early Childhood Workforce Index, State Profiles: District of Columbia, 2020.

[12] Lea J.E. Austin, Bethany Edwards, and Marcy Whitebook, Racial Wage Gaps in Early Education Employments, Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley, 2019.

[13] Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, Early Childhood Workforce Index, State Profiles: District of Columbia, 2020.

[14] Julia Isaacs et. al (2018).

[15] Deborah Phillips, Lea J.E. Austin, and Marcy Whitebook, The Early Care and Education Workforce, The Future of Children Journal, 26 (2): 139–58. And, Kashen, Julie, Halley Potter, and Andrew Stettner, Quality Jobs, Quality Child Care: The Case for a Well-Paid, Diverse Early Education Workforce, New York: Century Foundation, 2016.

[16] For a summary of the original report, see: Marcy Whitebook et.al, Worthy Work, STILL Unlivable Wages: The Early Childhood Workforce 25 Years after the National Child Care Staffing Study, Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, 2014, page 3. For the original report, see: Marcy Whitebook et. al, Who Cares? Child Care Teachers and the Quality of Care in America. Final Report, National Child Care Staffing Study, Child Care Employment Project, 1989.

[17] Judy Berman, Soumya Bhat, and Amer Rieke, “Solid Footing: Reinforcing the Early Care and Education Economy for Infants and Toddlers in DC,” DC Appleseed and DC Fiscal Policy Institute, 2016.

[18] The application process only requires early educators to be employed in an eligible position on or before May 16, but lawmakers approved funding for PEF to begin in September 2021, when the 2022 fiscal year began. See, Office of State Superintendent, Policy: Child Care Staff Eligibility and Payment Amounts for Early Childhood Educator Pay Equity Fund, May 16, 2022.

[19] Family Budget Calculator, Economic Policy Institute, 2022. Housing costs in the calculator are based on the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s fair market rents, which represent rental costs (shelter rent plus utilities) at the 40th percentile in a given area for privately owned, structurally safe, and sanitary rental housing of a modest nature with suitable amenities. The calculator uses two-bedroom apartments for families with one or two children.

[20] Julia Isaacs et. al, “Early Childhood Educator Compensation in the Washington Region,” the Urban Institute, April 2018.

[21] The local programs include DC HealthCare Alliance, educational scholarships funded through local dollars, the Home Purchase Assistance Program, housing subsidy vouchers, the Grandparent Caregiver Program, the Close Relative Caregiver Program, and other District benefit programs including Strong Families, Strong Futures.

[22] Some educators live in Maryland and Virginia but work in DC’s early education system. Because the Home Rule Act prohibits DC from levying income taxes on non-DC residents, early educators living in MD and VA pay income taxes where they live. Their pay supplements will be subject to state income taxes under current law.

[23] Final Report of the Early Childhood Educator Equitable Compensation Task Force, Submitted to the Mayor and Council of the District of Columbia, March 23, 2022, page 46.

[24] Office of State Superintendent, Policy: Child Care Staff Eligibility and Payment Amounts for Early Childhood Educator Pay Equity Fund, May 16, 2022.

[25] Ife Floyd et. al, TANF Policies Reflect Racist Legacy of Cash Assistance: Reimagined Program Should Center Black Mothers, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 2021.

[26] Martin Gilens, “Racial Attitudes and Opposition to Welfare,” Journal of Politics, Vol. 57, No. 11, November 1995; Martin Gilens, “’Race Coding’ and White Opposition to Welfare,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 90, No. 3, September 1996; and, Martin Gilens, Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, and the Politics of Antipoverty Policy, University of Chicago Press, 1999.

[27] Tazra Mitchell and LaDonna Pavetti, Life After TANF in Kansas: For Most, Unsteady Work and Earnings Below Half the Poverty Line, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 2018.

[28] Ife Floyd et. al, TANF Policies Reflect Racist Legacy of Cash Assistance: Reimagined Program Should Center Black Mothers, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 2021.

[29] Julia Isaacs et. al (2018).

[30] It DCPS teacher pay growth outpaces inflation, that would disrupt parity in pay with early educators’ salaries absent a policy change from lawmakers to eliminate the gap.

[31] These payments are supplemental to child care subsidy payments.

[32] The FY 2023 budget requires OSSE to develop a formula that accounts for “valid and reliable indicators of child, family, or community economic disadvantage and resources,” to ensure compensation funds are well-targeted. The FY 2023 Budget Support Act, Engrossed Version, page 111.

[33] Pre-pandemic, nearly all licensed infant and toddler slots in Wards 7 and 8 were used by children receiving subsidies, and over half of the children in licensed childcare in Wards 1, 4, and 5 are receiving subsidies. Office of State Superintendent of Education, FY19 Performance Oversight Questions, Attachment Q16, 2020.

[34] See, for example: Office of State Superintendent of Education, Modeling the Cost of Child Care in the District of Columbia, October 31, 2018. On page 5, the report concludes that, “In most cases, a provider’s estimated cost of delivering early care and education services exceeded the revenue generally available to provide care at different levels of quality.”

[35] A child care desert is any census tract with more than 50 children under age 5 that contains either no child care providers or so few options that there are more than three times as many children as licensed child care slots. Center for American Progress, Child Care Deserts Interactive, 2018.

[36] Data is through February 2022. Office of State Superintendent of Education, Responses to Fiscal Year 2021 Performance Oversight Questions, Attachment Q55, February 2022.

[37] Ibid; and, Office of State Superintendent of Education, FY19 Performance Oversight Questions, Attachment Q16, 2020.