DC’s progress on alleviating child poverty stalled in 2023, according to the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS), and remains closely linked to race, place, and age due to systemic inequities stretching back before America’s founding. DC child poverty remained statistically unchanged at 17.1 percent between 2022 and 2023 and was disproportionately felt by Black children, older children, and those living East of the River, data over a longer period show. DC lawmakers should prioritize policies that ensure every child in DC has the chance to live to their fullest, including by protecting vital lifelines and deepening investments in policies such as DC’s Child Tax Credit (CTC).

Families living below the official poverty line, or about $25,250 a year for a family of three, struggle to afford the essentials—such as rent, nutritious meals, and enriching learning environments—particularly in a high-cost place like DC. Poverty, especially when it’s persistent, harms children long-term. For example, children experiencing poverty tend to be worse off in a range of ways, including being more likely to enter school behind their peers, scoring lower on achievement tests, working less and earning less as adults, and having worse health outcomes. This pattern is especially clear for the poorest and youngest children and those who remain in poverty during childhood. There is even greater harm when children growing up poor are also living in high-poverty areas where the cumulative harm of hardship is magnified.

Nearly 1 in 3 Black Children in DC Live in Poverty

A history of racist policy and practice and its ongoing effects has resulted in tens of thousands of Black DC children growing up in families experiencing economic hardship. Nearly 1 in 3 Black children in DC lived in poverty on average between 2019 and 2023, compared to just 1 in 100 white, non-Hispanic children. (These data come from the American Community Survey’s 5-year estimates; even with five years of pooled data, small sample sizes for Latinx, Asian, and American Indian children were too small to report reliable estimates.)

Child Poverty is High East of the River

Child poverty is closely linked to place in DC and is heavily concentrated East of the River, which has suffered from systemic racism and economic divestment for decades. Wards 7 and 8 are predominately Black and had child poverty rates over 30 percent, on average, between 2019 and 2023. (Small sample sizes make other ward-level comparisons unreliable, even with five years of pooled data. However, based on other economic and demographic data, it is reasonable to assume that child poverty is lower in predominantly white and higher wealth areas such as Wards 2 and 3.) This data underscores that DC must do a better job of ensuring that all DC children can thrive regardless of ward.

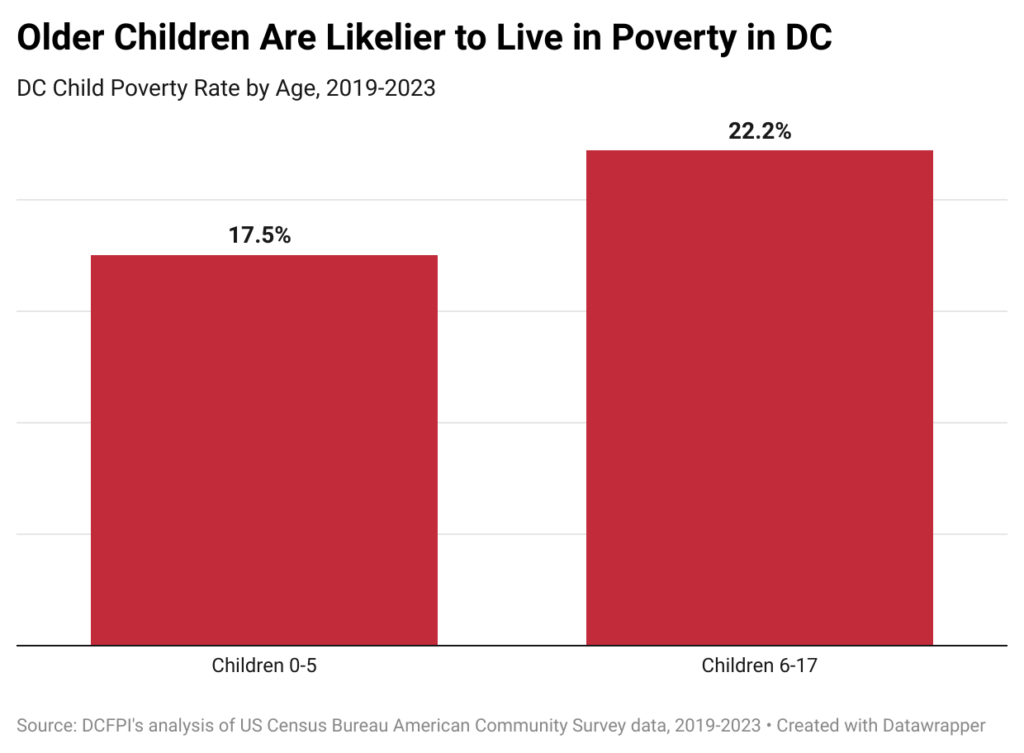

Older Children in DC are More Likely to Live in Poverty Than Children Ages 0-6

Child poverty also varies by age in DC, with older children likelier to live under the poverty line (Figure 1). This bucks national trends: typically, younger children experience poverty at a higher rate compared to older children in part because caregivers tend to earn less income when their children are younger. However, on average between 2019 and 2023, children aged 6 to 17 in the District experienced poverty at a rate of 22 percent, which is higher than the 17 percent rate for children under the age of 6. Compared to other states, the District is tied for 5th for the highest child poverty rate for children aged 6 to 17. DC’s public investment in early learning opportunities for young children like universal pre-k have been shown to improve the labor force participation of DC mothers and may be part of the reason that DC’s young child poverty rate doesn’t follow national trends.

DC Lawmakers Must Do More to Reduce Child Poverty, Set Children Up to Thrive

Getting cash and economic supports to families that have poverty-level and low incomes can make a long-lasting difference in children’s lives and how they fare as adults. DC has made large investments in families with children through the child care subsidy program, universal pre-kindergarten classrooms, cash pilots for single mothers, local food aid, and DC’s Earned Income Tax Credit and CTC—among many other targeted supports. The Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), an alternative poverty measure that accounts for public assistance and better captures living expenses like geographic-specific housing costs, shows that local and federal supports are lowering DC child poverty rates compared to the official poverty level close to three percentage points.

DC must do more to reduce poverty, particularly when federal lawmakers are poised to make deep cuts to critical income supports to families struggling to make ends meet. DC leaders must rise to the occasion by protecting the most vulnerable residents and fortifying local programs that build economic security. To take aim at child poverty, one item on their agenda should be to expand DC’s CTC to reach all children, including those aged 6 to 17 who are currently excluded, and to increase the maximum credit to at least $1,500 per child for families with the lowest incomes. A $1,500 per child credit would cover nearly three months of groceries and two months of rent for a single parent with two kids while also reducing child poverty relative to the SPM.