This report is part of a series of research and analysis on how DC can build a tax system that embodies racial justice in both its design and the public investments it provides. Find the full series here.

Nearly a century of racist policies and practices such as racially restrictive covenants and lending discrimination have cemented racial disparities in homeownership and home values that are, in turn, drivers of DC’s extreme and persistent racial wealth gap. District lawmakers have begun efforts to address these racial disparities but to succeed, they must address property tax policies that concentrate wealth among the already wealthy while raising revenue for programs that can stabilize housing and create wealth building opportunities for Black residents.

DC’s single-rate property tax imposes the same rate on $300,000 homes as it does on multi-million-dollar homes. By taxing residential property more progressively, the District would help correct the racist harm of past policies in the tax system and raise tens of millions of dollars in revenue to support Black housing security and homeownership.

Summary

- The homeownership rate for Black households (35 percent) lags significantly behind the rate for white households (50 percent).

- Only 8.4 percent of homes purchased between 2016 and 2020 were affordable to the average first-time Black homebuyer, while 71.4 percent of homes were within reach of the average white first-time homebuyer.

- DC’s property tax system uses a single rate, meaning that an owner of a multi-million-dollar home pays the same property tax rate as someone who owns a $300,000 condo.

- The District can raise $57 million using a progressive marginal property tax structure that raises taxes on extremely high value homes, impacting tax bills for only 5 percent of homeowners.

- DC should use those resources to stabilize housing and create wealth building opportunities for Black residents.

Intentionally Racist Policy and Practice Created and Cemented Racial Disparities in Homeownership and Wealth

For almost a century, legislators on both the federal and local levels have incentivized and subsidized homeownership as the dominant method for individual wealth creation and access to the middle class. However, generations of racist policies and practices, including racially restrictive housing covenants, Jim Crow laws, redlining, and lending discrimination ensured those opportunities primarily went to white people and have contributed to an enormous and persistent racial wealth gap.[1],[2]

In 2021, the homeownership rate for white, non-Hispanic households in DC was 50 percent, compared to 35 percent for Black households.[3] Racial disparities in both income and intergenerational wealth means that Black DC residents are less likely to be able to afford a home in the District. An analysis by the Urban Institute found that only 8.4 percent of homes purchased between 2016 and 2020 were affordable to the average first-time Black homebuyer, while 71.4 percent of homes were within reach of the average white first-time homebuyer.[4]

Because homeownership is one of the main ways people build wealth, racial disparities in homeownership and home values contribute to the racial wealth gap. Recent estimates show that the median white wealth in the United States is between 6.9 to 10 times greater than the median wealth held by Black Americans.[5],[6] A 2016 study showed that, in the DC area, white households have 81 times the wealth of Black households.[7]

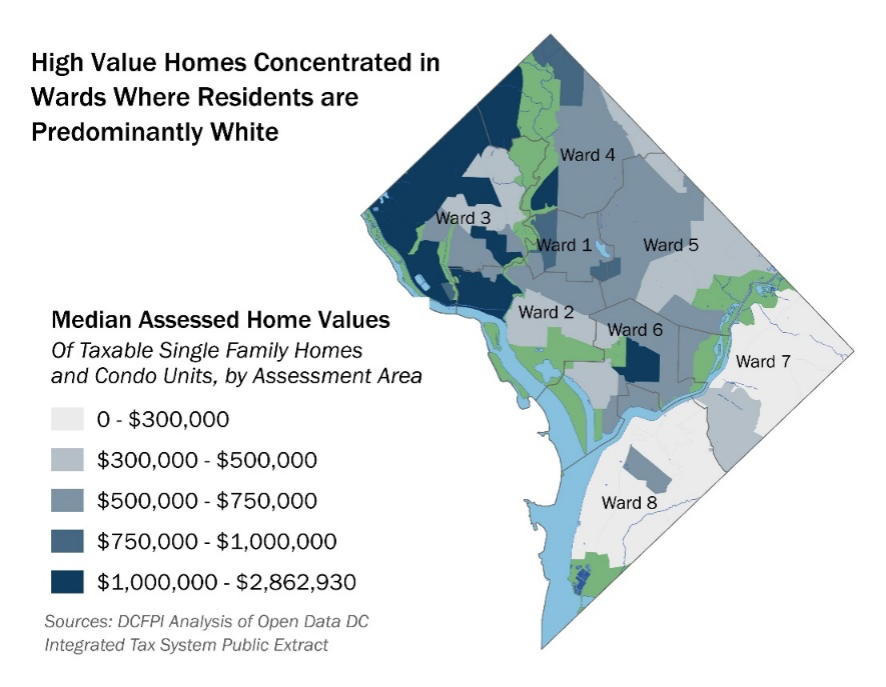

Of course, addressing racialized wealth disparity goes beyond raising the Black homeownership rate. As Dr. Dorothy Brown describes in The Whiteness of Wealth, homeownership in America “is rigged and has been from the beginning.”[8] As Brown explains, even when Black Americans are able to become homeowners, they frequently face a myriad of barriers that prevent them from benefiting from the wealth accumulation and financial security of homeownership that white Americans have enjoyed for generations. Take, for example, the racial gap in the market appreciation of home values: white homeowner preferences for white neighborhoods suppress the market value of houses in racially diverse or predominantly Black neighborhoods while simultaneously pushing up the value of houses in all-white neighborhoods.[9] This phenomenon plays out in DC where median home values are more than three times higher in predominantly white Wards 2 and 3 than they are in predominately Black Wards 7 and 8. Likewise, the home value of the typical Black homeowner is about two-thirds the home value of the typical white homeowner. [10] Other challenges to wealth building through homeownership for Black residents, as laid out by Mayor Bowser’s Black Homeownership Strikeforce, include too few quality affordable homes, limited financing, and the preservation of Black homeownership. [11]

DC’s Racist History Shaped Racially Disparate Homeownership and Home Values

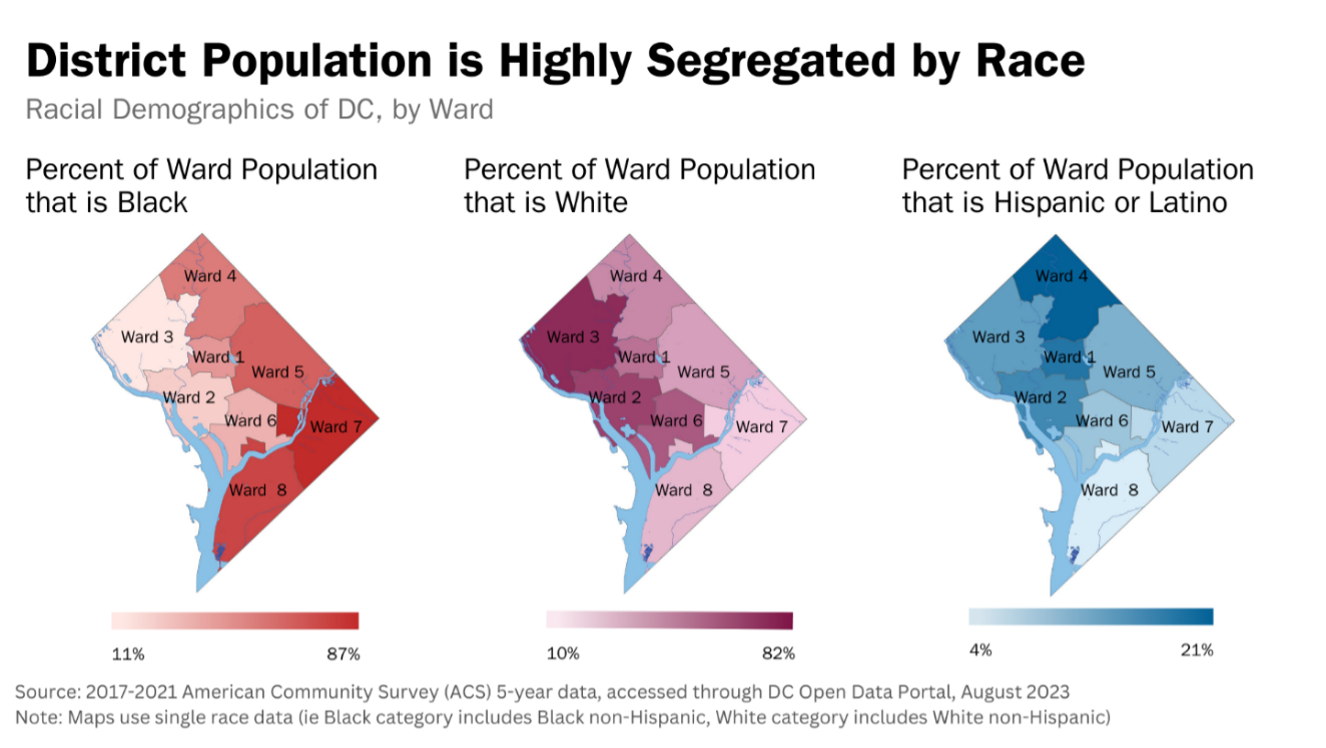

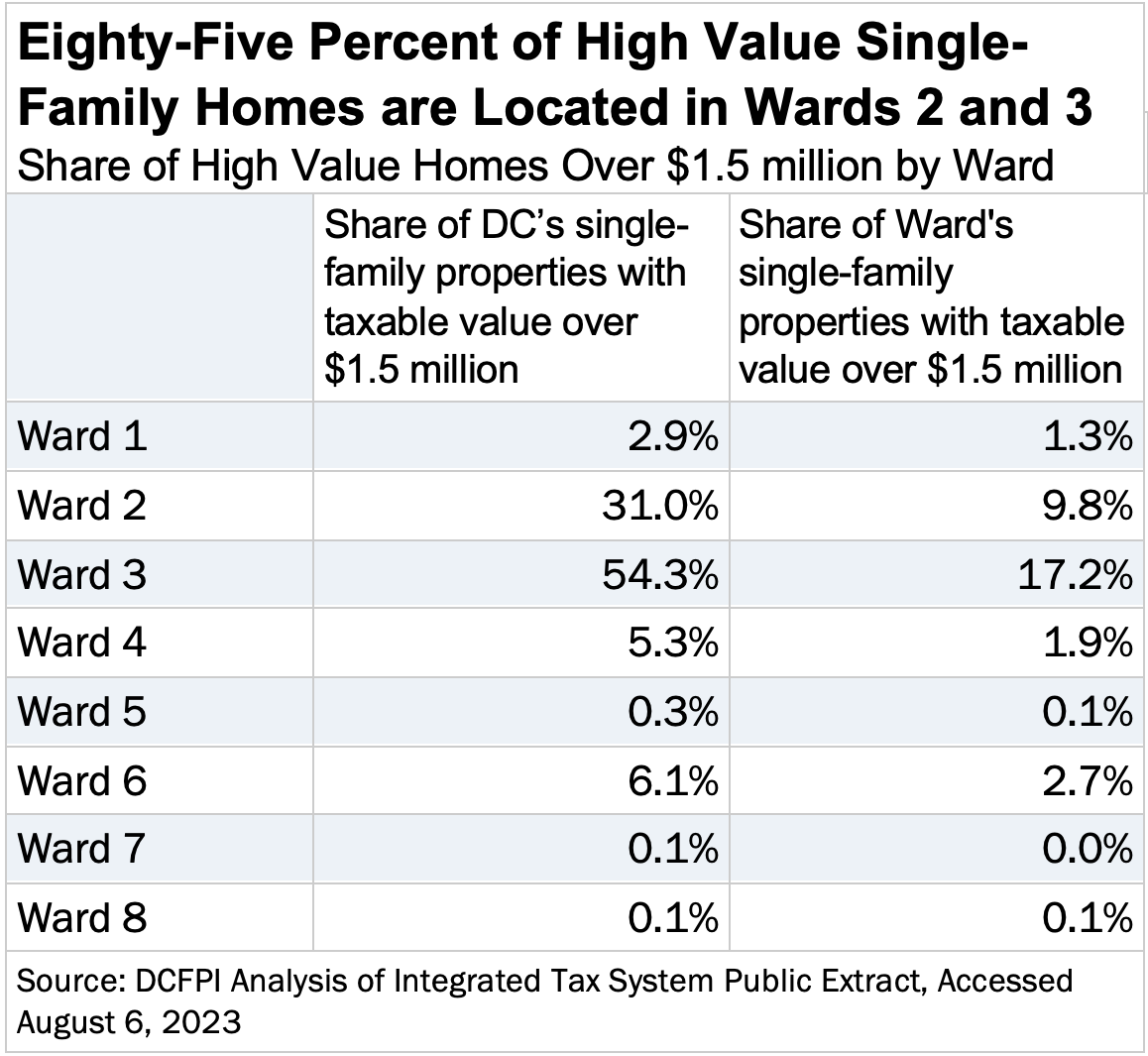

The legacy of DC’s racist housing policies, consistent with policies nationwide, is apparent in today’s starkly divided housing landscape. Black Washingtonians largely continue to live in highly segregated neighborhoods (Figure 1), many with limited access to basic amenities such as grocery stores. Meanwhile, 85 percent of very high value single-family homes – or those valued over $1.5 million – are located in Wards 2 or 3, where respectively, 75 and 82 percent of residents are white (Figure 2).

During the first half of the 20th century, racially restrictive housing covenants defined where Black Washingtonians could live. Both developers and organized white residents systematically barred Black and other residents of color from entire blocks and neighborhoods.[12] The federal government further institutionalized racial segregation by, for example, making race a criterion for insuring mortgages and barring Black households from qualifying for mortgages from mainstream banks.[13]

By artificially enhancing the value of areas where only white people lived, covenants incentivized the redevelopment of Black land into white-only neighborhoods while disincentivizing investment in areas where most Black DC residents lived. For example, white community members in 1920s Chevy Chase worked with the National Capital Park and Planning Commission to use eminent domain to seize land from a neighboring community of Black families for a new whites-only school and recreation center.[14],[15]. As private “revitalization” efforts made neighborhoods such as Chevy Chase, Georgetown, and Foggy Bottom whiter and more expensive, Black residents were restricted to areas where they already predominated. The few neighborhoods where Black residents could go grew increasingly crowded and increasingly poor as Southern migrants arrived.[16]

White households that owned homes with covenants in amenity-rich neighborhoods were able to pass that value on to future generations, and that intergenerational wealth for white residents came at the direct expense of Black residents.[17] In addition, because Black residents have been excluded through policy and practice from the full benefits of homeownership for so many decades, during which there were major booms in the housing market, the compounding effect has been self-perpetuating gaps in white-Black home values and white-Black homeownership rates. These gaps result in white families consistently benefitting significantly more from homeownership than Black families and contributes to the further concentration of wealth among predominantly white residents.[18]

A property tax system that is racially and economically just must help address these historic harms. First and foremost, that means it must be progressive, requiring the wealthiest people to pay a higher proportion of their income in taxes than those with fewer or no assets. Currently, the District taxes all residential properties, regardless of value, at the same rate of $0.85 per $100 of taxable assessed value. The regressive effect of this single-rate structure is offset somewhat by deductions and credits for people with low incomes and other populations, but still results in lower income households paying a greater share of their income in property taxes (either directly or passed through to rent) than higher income households.[19]

A racially equitable property tax would also help facilitate greater homeownership and wealth building opportunities for Black and non-Black people of color who have historically been shut out or forcibly removed from areas of the District with the highest residential property values, best schools, and richest amenities.

How DC Taxes Residential Property

Assessed Value: The Real Property Tax Administration of the Office of Tax and Revenue assesses each property in the District and assigns it an “assessed value” based on a range of characteristics, including size, age, condition of the building, among other things. The assessed value should be similar to what the home’s sale price would be, though actual sale prices can differ significantly from the assessed value due to demand, interest rates, and other neighborhood factors.

Taxable Assessed Value (or Taxable Value): While property assessment is the starting point for a property owner’s tax liability, many homeowners do not pay taxes on the full assessed value of their homes. DC’s homestead deduction, for example, permits property owners who live in their home to subtract a certain amount – $84,000 in 2023 – from the full assessed value of their home. The property tax rate of $0.85 per $100 is applied to that reduced amount.[20] The District also has several other income-based programs that reduce property taxes for seniors, homeowners with disabilities, and veterans, and homeowners with very low incomes.

Methodology

DCFPI conducted revenue analysis on all single-family properties, which includes detached single-family houses, row homes, and individual condo units. The analysis also included residential conversions, which are formerly single-family properties that have been converted into multiple units (e.g., a row house with a separate basement unit). The analysis uses a progressive marginal rate structure and excludes properties that receive any property tax deduction or credit based on income or for seniors, people living with disabilities, or veterans; property taxes for these groups would not change under this proposal.

The analysis also excluded co-op buildings and multi-family rental properties. DCFPI chose not to include multi-family rental properties in this analysis because of concern that significant increases in costs for multi-family rental properties would adversely affect housing affordability on a large scale.

DCFPI selected the $1.5 million threshold for property tax rate increases for two primary reasons. First, the number of homes begins to decline rapidly after the $1 million mark and the $1.5 million threshold allowed for a clean cut-off of 5 percent of single-family homeowners. Second, $1.5 million is higher than the average single family home value of $1.1 million, as reported by the Office of the Chief Financial Officer for fiscal year (FY) 2022, and it is about 2 to 2.5 times the median home value according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.[21] This leaves a substantial “cushion” for homeowners in rapidly rising housing markets within the District, whose incomes may not match the increased values of their homes.

The District Should Advance Racial Equity and Raise Revenue Through A Progressive Marginal Property Tax

One way the District can pursue racial equity in housing, homeownership, and the tax system is by introducing marginal progressivity into its residential property tax. Doing so will not only create a more equitable distribution of tax responsibility, but also raise revenue for the District. Making even small adjustments to the tax rate for extremely high value properties could raise tens of millions of dollars in revenue that can be used to bolster programs that help close DC’s racial wealth and homeownership gap.

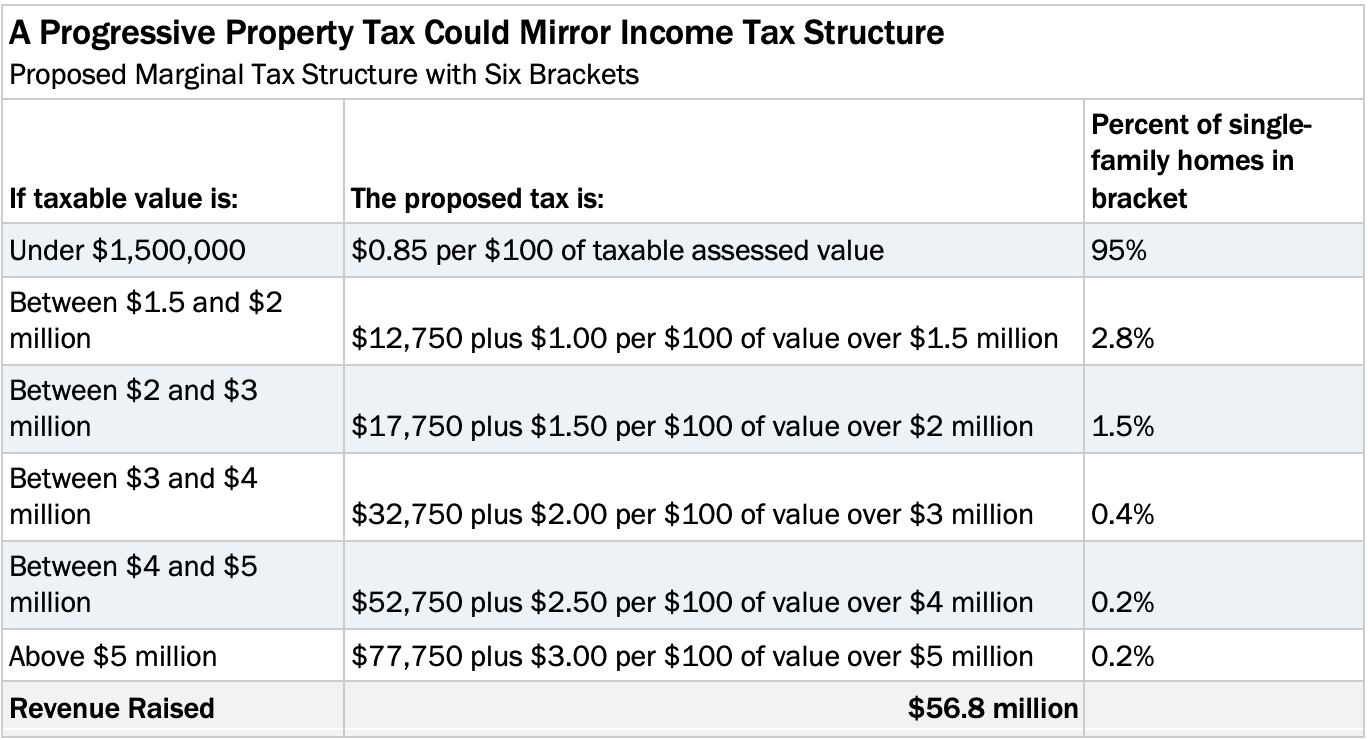

The District already uses a marginal rate structure to tax income and could model its property tax system based on that structure. A truly progressive property tax structure would split District properties into value brackets, each with a progressively higher marginal rate.[22] The Office of Tax and Revenue could break DC’s taxable real estate properties into six value brackets, similar to our income tax structure, as detailed in Table 1.

None of these tax policy proposals would raise taxes for the 95 percent of homeowners whose homes have a taxable value of less than $1.5 million. Homes valued at $1.5 million or less after subtraction of the homestead deduction would continue to be taxed at the same rate of $0.85 per $100 of taxable value. Also excluded are any homes valued above the $1.5 million where the homeowner received a homestead-based deduction or credit, which means that property taxes for veterans, seniors with low incomes, or homeowners with disabilities would not increase under these proposals.

Homes with a taxable value of $1.5 million to $2 million would pay just $0.15 more, or $1.00 per $100 of taxable assessed value. For each subsequent bracket, the marginal rate would increase by $0.50 per $100 of taxable assessed value. This proposal would yield $56.8 million in additional revenue for the District through higher taxes on just 5 percent of homeowners. The District could index the $1.5 million threshold to home price appreciation, pegging it to the 95th percentile of homes. This would ensure that as property values rise in future years, the higher rates in a marginal rate structure would continue to apply only to the top 5 percent of homes.

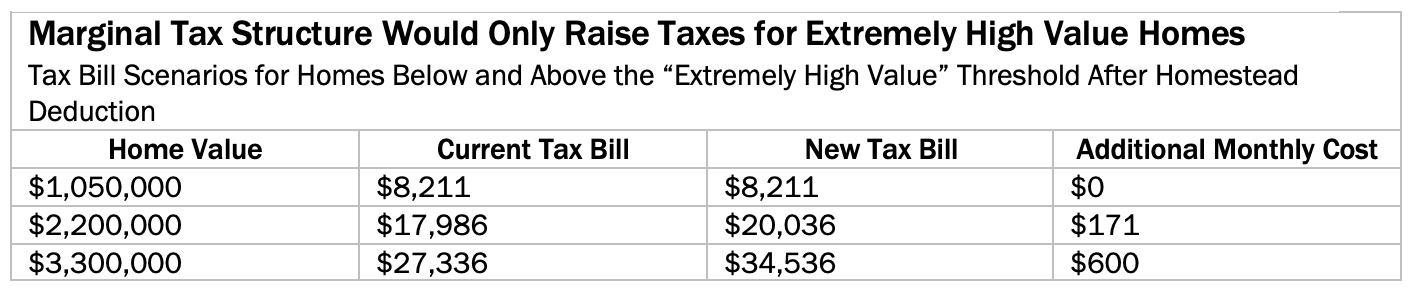

This structure reflects the reality of DC’s housing market. In some well-off neighborhoods where home prices have soared, homeowners who may not otherwise be particularly wealthy or high income can find themselves living in homes assessed at $1 million or even more as a result of years of rising housing assessments. This proposed structure keeps their property taxes unchanged or, at somewhat higher taxable values, keeps the tax increases to a moderate level. The proposed marginal rate structure would increase property taxes by less than one-tenth of one percent of home value or just $171 per month for owners of a home with a taxable value of $2.2 million (Table 2). For an owner of a $3.3 million home, annual property taxes would rise by about two-tenths of one percent, or $600 per month.

These increases are unlikely to affect the finances of residents who can afford to buy and maintain multi-million-dollar homes. For example, a person buying a $3 million home today would likely need $600,000 or more in cash for a down payment, which would require very high income and likely other property or assets to draw on. Indeed, the rough rule of thumb that a new home should not cost more than three times of a household’s income would suggest that a purchaser of a $3 million home have income of about $1 million.[23] For the vast majority of homeowners with homes valued over $1.5 million – over 85 percent, in fact –those homes are located in Wards 2 and 3 where incomes in the District are the highest (Table 3). At the same time, DC also has hundreds of “trophy homes,” those valued at $5 million or above, that are a function of tremendous wealth and whose owners can clearly afford a substantial tax increase that allows for raising revenue to dedicate to making housing more affordable and homeownership more accessible for others.

Neighboring Counties Have Higher Residential Property Tax Rates than the District

Like DC, Fairfax County, Arlington County, and Silver Spring tax residential properties at the same rate regardless of assessed value.[24] However, the residential property tax rates in those jurisdictions are higher than DC’s rate. The District would raise $735 million more in property tax revenue if it levied Silver Spring, Maryland’s rate of $1.285 per $100 on all properties, or $34 million if it mirrored that rate on single-family homes valued over $1.5 million .

Likewise, DC would raise $450 million more from all residential properties or $18.4 million from high value homes if it used Fairfax County’s rate of $1.095 per $100 of assessed value.[25] The District would bring in $327 million on all residences or $11.9 million from high value homes at Arlington County’s rate of $1.013 per $100 of assessed value.[26]

The District Should Direct Additional Revenue Toward Housing Security and Wealth-Building Programs

Additional revenue generated from a more progressive property tax structure should be dedicated to programs that close the racialized homeownership gap or improve housing stability for residents with low incomes. The District could use this additional revenue to expand Schedule H – DC’s property tax benefit program for residents with low incomes. DC could vastly improve the effectiveness of the program in two ways: first by removing the cap on the credit amount in order to ensure that amount actually increases with need, and secondly, by allowing for incremental income thresholds that ensure eligible households don’t see large shifts in property taxes owed due to increases in their incomes. The current cap and thresholds keep this program from being a more robust support for longtime DC homeowners who have low incomes and struggle to hold onto their family home as an asset due to rising home values and property taxes.[27]

The District could also use the additional revenue to increase down payment assistance. DC’s Black Homeownership Strikeforce identified the Home Purchase Assistance Program (HPAP) as the District’s main tool for tackling the racial homeownership gap.[28] In FY 2022, 74 percent of recipients of HPAP borrowers were Black and 61 percent identified as female.

In FY 2023, the District more than doubled the maximum loan amount to $202,000 in an effort to expand homeownership opportunities for HPAP program participants amidst high housing prices.[29] However, the budget did not expand funds for the program, leaving it with insufficient funding to meet demand. HPAP recipients continue to face challenges such as high interest rates and high competition for very few homes available for purchase.[30],[31] With additional revenue raised through a progressive property tax, the District could more than double the current HPAP budget, which received $26 to help meet the substantial demand for home purchase assistance.

[1] Richard Rothstein, “The Color of Law,” Liveright Publishing Corporation: New York, 2017.

[2] Emily Moss, Kriston McIntosh, Wendey Edelberg, and Kristen Broady, “The Black-white Wealth Gap Left Black Households More Vulnerable,” Brookings, December 8, 2020.

[3] See “Black Homeownership Strikeforce, Final Report.” Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development, October 2022.

[4] See “Black Homeownership Strikeforce, Final Report.” Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development, October 2022.

[5] Rashawn Ray, Andre Perry, David Harshbarger, Samantha Elizondo, Alexandra Gibbons, “Homeownership, Racial Segregation, and Policy Solutions to Racial Wealth Equity,” Brookings, September 1, 2021.

[6] Emily Moss, Kriston McIntosh, Wendey Edelberg, and Kristen Broady, “The Black-white Wealth Gap Left Black Households More Vulnerable,” Brookings, December 8, 2020.

[7] Kilolo Kijakazi, Rachel Marie Brooks Atkins, Mark Paul, Anne Price, Darrick Hamilton, William A. Darity Jr. November 2016, The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital, Urban Institute.

[8] Dorothy Brown, “The Whiteness of Wealth,” Crown: New York, 2021, 94.

[9] Ibid, p82.

[10] See “Black Homeownership Strikeforce, Final Report.”

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Legal Challenges to Racially Restrictive Covenants,” Prologue DC.

[13] “How the Federal Housing Administration Shaped DC,” Prologue DC.

[14] “Black Families Once Owned Part of Lafayette Park,” Historic Chevy Chase DC, Accessed on October 6, 2022,.

[15] Neil Flanagan, “You Should Know About George Pointer,” Washington City Paper, July 19, 2018,

[16] Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital (The University of North Carolina Press, 2017), pg.259.

[17] Sarah Jane Schoenfeld, Op-Ed: Reparative Justice for DC: Why Reparations are Due and How, Medium.com.

[18] Dorothy Brown, “The Whiteness of Wealth,” Crown: New York, 2021, 94.

[19] See “District of Columbia: Who Pays? 6th Edition,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, October 17, 2018.

[20] The amount of the exemption changes annually to account for cost-of-living adjustments. See “D.C. Tax Facts,” 2023; and “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022.

[21] See “Economic and Revenue Trend Reports, August 2023,” Office of the Chief Financial Officer and “Zillow Home Value Index (ZHVI) for All Homes Including Single-Family Residences, Condos, and CO-OPs in the District of Columbia,” Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, October 2023.

[22] DCFPI conducted analysis on all single-family properties, including row homes, individual condo units, detached single family houses, etc. The analysis also included residential conversions, which are formerly single-family properties that have been converted into multiple units (e.g., a row house with a separate basement unit). The analysis excluded co-op buildings and multi-family rental properties. DCFPI chose not to include multi-family rental properties in this analysis because of the concern that significant increases in costs for multi-family rental properties would adversely affect affordability on a large scale.

[23] See Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, “How Much Mortgage Can I Afford?”

[24] Within the same geographic area.

[25] See “Real Estate Assessments & Taxes,” Fairfax County, VA.

[26] See “Tax Rates,” Arlington, VA.

[27] See analysis by Adam Langley of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy in his presentation to the DC Tax Revision Commission, “Strengthening Property Tax Relief in DC,” June 20, 2023.

[28] See “Black Homeownership Strikeforce, Final Report.”

[29] Melissa Lang, “DC to Provide Up to $200K to First-Time Home Buyers in Hot Market,” Washington Post, August 22, 2022.

[30] See “Performance Oversight Responses.” Department of Housing and Community Development, February 10, 2023.

[31] Michael Bryce Sadler, “D.C. home buyers’ assistance program is out of funds, officials say,” Washington Post, July 1, 2023.