This report is supported by a grant from the William S. Abell Foundation.

DC residents returning from incarceration often come home to homelessness, which means that the District’s efforts to reduce homelessness must include doing more to help returning citizens find stable housing. Nearly three of five DC individuals experiencing homelessness—57 percent—have been incarcerated, according to a 2019 assessment, and 55 percent reported that incarceration had caused their homelessness. This means that almost one-third of individuals who experience homelessness in DC connect that to their incarceration.

Returning citizens[1] typically have low incomes and face the same housing challenges as other District residents with low incomes, but they also face many unique challenges. Returning citizens experience mental health problems at higher rates than other residents. Being separated from family and community while incarcerated leads to weaker bonds with loved ones and means many don’t have anyone they can stay with upon release. Most returning citizens are released from prison without any savings and without a job, and as a result they lack funds for housing application fees, security deposits, and rent. They also face high rates of discrimination in the housing market, even though this discrimination is illegal.

Research has consistently found, and agencies serving the District’s returning citizens agree, that securing housing is the most important need and biggest challenge for them. “Housing is the most critical step to successful reintegration because it establishes stability for other needs to be met such as employment, substance abuse, and mental health treatment.”[2] When basic needs like housing aren’t met, “individuals are at greater risk of returning to crime and being reincarcerated.”[3] A New York City study found that those who enter a homeless shelter upon release were seven times more likely to abscond from parole than those who had housing.[4]

This report makes recommendations for improving housing and other services to reduce homelessness among returning citizens.[5] It reflects research but also direct input from returning citizens through three focus groups with returning citizens held in late 2018 and early 2019. Each focus group was coordinated with a non-profit organization who invited their clients to attend. Most of the problems and solutions outlined here were inspired by what was shared in these focus groups. Some were suggested by service providers and government officials who directly work with returning citizens.

The housing and shelter recommendations include:

- Creating a new program to connect returning citizens with family or friends and offering financial assistance and services to support these living arrangements.

- Creating and expanding medium-term housing options, in recognition that the first years following incarceration are especially important and that the risk of recidivism is highest in this period. A joint Transitional Housing (TH)-Rapid ReHousing (RRH) program could provide individualized services and financial support for at least three years. DC Flex, a new four-year program that helps bridge the gap between a person’s income and rent, could be expanded to enroll returning citizens.

- Prioritizing returning citizens with high service needs and high likelihood of recidivism for Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH), DC’s program for residents facing chronic homelessness.

- Creating shelter beds especially for returning citizens with services to meet their unique needs.

Beyond housing, the other recommendations are:

- Strengthening mental health services by ensuring mental health providers are part of discharge planning and that services are available for all who need them.

- Helping individuals find and keep employment.

- Preparing individuals for return by connecting them to friends and family and DC service providers while still incarcerated. The days and months following release are key to success, so these connections need to be available immediately.

Finally, the District needs a strategic plan to tackle homelessness among returning citizens that includes a needs assessment and that assigns roles and responsibilities to the many government agencies involved in reentry. There are numerous federal and local agencies that play some role in DC’s criminal justice system, with no clear responsibilities for addressing the housing needs of returning citizens.

While it would be an expensive undertaking, taking full control of our criminal justice system would make it easier to solve many of the problems outlined in this paper. DC would create its own courts, prison, halfway houses, and parole system. DC would control prison and halfway house programming to ensure that each inmate has access to mental health services, education, employment, and housing location assistance.

Helping Returning Citizens Integrate is a Matter of Racial Justice

Returning citizens from Bureau of Prison facilities are overwhelmingly Black and male. In 2015, nearly 95 percent were Black and nearly 96 percent were male.[6] This reflects racial discrimination and disparities in police interactions, arrest, and sentencing. “Black and White Americans encounter the police at different rates and for different reasons, and they are treated differently during these encounters,”[7] according to the Sentencing Project, both because of formal policies and the choices made by police officers. Officers are more likely to stop Black drivers and, once stopped, more likely to search them as well. “Stop and frisk” policies, in which officers search individuals for contraband, are often implemented in Black neighborhoods against Black residents. As a result, people of color are also more likely to be arrested than whites.

Additionally, people of color are more “likely to be charged more harshly than whites; once charged, they are more likely to be convicted; and once convicted, they are more likely to face stiff sentences – all after accounting for relevant legal differences such as crime severity and criminal history.”[8] For example, white people engage in drug offenses at a higher rate than Black people nationally, but Black people are incarcerated for these offenses at a rate that is ten times greater.[9] This has large implications for DC’s returning citizens as the largest group of DC’s returning citizens have a drug offense.[10]

This report recommends steps that the District should take to help returning citizens, starting with housing and homeless services. All of the focus group participants cited housing as an urgent concern. Most were in temporary situations, such as transitional housing or a halfway house, and had little idea of where they could live once these stays were over.

Why Returning Citizens Experience High Rates of Homelessness

There are three key factors that contribute to and complicate homelessness among people leaving prison, according to the Vera Institute:

- Many returning citizens face the same challenges that lead to homelessness among the general population;

- Returning citizens face unique barriers to housing associated with their criminal justice system involvement; and

- There is a lack of ownership of the problem among government agencies and community organizations.[17]

Many Returning Citizens Face the Same Challenges that Lead to Homelessness Among the General Population

Returning citizens share many characteristics with households who struggle to afford housing or experience homelessness. About a third of returning citizens lack a high school degree.[18] Fair Market Rent (FMR) for a one-bedroom apartment in the District is $1,561.[19] To afford this rent, a worker earning minimum wage would have to work 91 hours per week.[20] As a result, many DC residents cannot afford to move into their own housing, and those in their own housing are at great risk of being evicted and experiencing housing instability or homelessness.

Returning citizens have higher rates of mental health issues than the general population. 30 percent of individuals released to Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA) supervision in 2018 reported a mental health need.[21] CSOSA serves individuals who have been released on parole, probation, or supervised community release following incarceration. And people with mental illness entering supervision from prison were more likely to lack stable housing.[22] This is consistent with the fact that mental illness is a contributing factor to homelessness. A national study found that at least 25 percent of people experiencing homelessness have a serious mental illness compared to just 4.2 percent of the general population.[23]

Additionally, it is likely many returning citizens with mental health needs do not receive adequate services while incarcerated. The BOP classifies just 3 percent of its inmates as having a mental illness serious enough to require regular treatment.[24] This is much lower than the 20 to 30 percent who receive regular treatment in the state prison system and suggests that BOP underestimates the extent of this need.[25] The BOP has not allocated the necessary funding to serve all those with critical needs.[26]

Returning Citizens Face Unique Barriers to Housing Associated with Their Criminal Justice System Involvement

In many ways, DC’s returning citizens face special challenges to securing housing.

- Imprisonment far from home: DC residents are sent to federal prisons that are far away, making it difficult to maintain relationships with family or friends they could stay with upon return.

- Low incomes and savings: Very few, if any returning citizens have funds for security deposits and first month’s rent. Only some individuals are allowed to work during incarceration, and those that do only earn between 12 cents and $1.15 per hour.[27] This means they are likely to not have any savings when released. [28] And most returning citizens do not have employment lined up before their release, leading to time without any wages.[29] Once employed, after controlling for other factors, incarceration is associated with an income loss of between 10 to 30 percent.[30] Finally federal benefits are discontinued during incarceration and cannot be reapplied for until release, meaning returning citizens go months without benefits.[31]

- Discrimination: Despite protections against housing discrimination, staff who work with returning citizens in DC report that clients regularly are discriminated against when they apply for housing.[32]

Focus group participants overwhelmingly reported that returning citizens have specific needs and benefit from specialized services and being in the company of other returning citizens. Most described incarceration and reentry as particular challenges, different from experiencing homelessness or housing instability more generally. A 38-year-old female participant living in Jubilee’s program reported that she had women in the program she could share ideas with, as well as a case manager. She described it as being “just a lot of support,” and pointed out that this was something that she had never experienced before.

A Lack of Ownership of the Problem Among Government Agencies and Community Organizations

The Vera Institute finds that “providing housing assistance to people leaving prison does not fall easily within the purview of criminal justice, homeless services, or housing development agencies.”[33] DC’s unique criminal justice system makes this even more complicated as the District has limited influence on federal agencies. There are also numerous local agencies that have responsibility for some part of the problem or serve part of the population. And different agencies have different levels of expertise as it relates to helping returning citizens or helping individuals experiencing homelessness. (See Appendix 2 for agency descriptions.)

For returning citizens with behavioral health needs, it is even more complicated. The BOP, CSOSA, Department of Behavioral Health (DBH) and Core Service Agencies, nonprofit behavioral health providers who contract with the District, have overlapping transition planning duties, including planning for housing.[34] Different agencies provide these services “in different cases for different reasons.[35] DBH has agreed that there should be “increased coordination” among agencies and private partners as these consumers face additional barriers that make obtaining stable housing “more challenging.”[36]

Recent Positive Developments

Some recent efforts in the District hold promise for helping returning citizens meet their housing needs.

The Criminal Justice Coordinating Council is writing a research brief on housing and homelessness needs for justice-involved individuals. This is an opportunity for relevant stakeholders to come together to discuss the needs of returning citizens and to collect data on their housing situation. This report should look to the Interagency Council on Homelessness Strategic Plan, Homeward DC, for information on modeling the need, current programming, and the intersections of various agencies.

DHS has just launched Project Reconnect, a new Diversion and Rapid Exit program for unaccompanied homeless adults that gives priority to returning citizens. Diversion aims to assist residents in avoiding shelter if possible while Rapid Exit assists those already in shelter with leaving quickly.[37] Recognizing that the days immediately after release are high stress and high risk for reoffending, returning citizens will be eligible immediately upon accessing homeless services.

Finally, DC’s READY Center expanded to those returning from the BOP. The READY (Resources to Empower and Develop You) Center is a one-stop shop where returning citizens can access vital documents, housing, employment, healthcare, and educational services. The READY Center is a collaboration between the Mayor’s Office on Returning Citizen Affairs (MORCA), Department of Corrections (DOC), Department of Behavioral Health (DBH), Department of Human Services (DHS), Department of Employment Services (DOES), Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), and community-based organizations.[38] Originally the READY Center was limited to citizens returning from Department of Corrections facilities, but has recently been expanded to include citizens returning from BOP facilities.[39]

Policy Recommendations

Reducing homelessness among returning citizens would help one of DC’s most vulnerable populations at their most vulnerable moments. It would make an important contribution to reducing DC’s shockingly high rate of homelessness, and it would help ensure that returning citizens can reintegrate in their community successfully.

Create a Strategic Plan and Needs Assessment on Housing Issues Facing Returning Citizens

The two existing collaborative efforts—the Interagency Council on Homelessness (ICH) and the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council’s (CJCC) Reentry Steering Committee—should convene a working group to tackle the issue of homelessness among returning citizens, with participation from all key stakeholders, including returning citizen, advocates, and nonprofit providers. Given the number of agencies involved and the overlap of missions, it will be critical to map out roles and responsibilities.

- Perform a needs assessment and create a strategic plan. The working group should develop a needs assessment and strategic plan to identify all housing and shelter services that specifically serve returning citizens and all funding streams. As discussed above, housing is especially crucial in helping returning citizens who have mental health conditions follow their treatment plans so the needs of this population should be an explicit focus in the plan. The plan should align with the ICH’s Homeward DC plan to end long-term homelessness. Finally, it should set targets with timelines for filling unmet needs and estimates of the costs of these targets.

- Moving forward, the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council should be responsible for coordinating ongoing efforts, bringing stakeholders together, updating need estimates, and monitoring progress. The CJCC’s Reentry Steering Committee is already tasked with developing an “action plan for reentry that provides strategies for connecting returning citizens with housing” and other services.[40] This Committee should add members from the Interagency Council on Homelessness and the Department of Human Services to bring needed homelessness expertise to the group.

Strengthen Housing and Homeless Services

Connecting returning citizens with housing should be the top priority. Otherwise individuals end up staying in large low barrier shelters where case management services are very limited.

Implement housing evaluations. Every person should have a housing evaluation at least three months prior to their release date. Some may be able to move back to the housing they had prior to incarceration without any assistance. Others may need assistance accessing the subsidized housing programs they lived in prior to incarceration or identifying someone they could live with upon release. Still others may have no options other than the homeless services system, and they should be offered the homelessness assessment that identifies the person’s housing-related service needs. If the person will likely be matched quickly to housing, the assessor should help the person gather documents they will need to enter the program such as birth certificate or photo ID.

The Housing Evaluation should be performed by staff with knowledge of the parole/probation systems, the homeless services system, and DC Housing Authority programs. The staff should also have experience with housing mediation like that done in the family Homeless Prevention Program (HPP) and Project Reconnect, the new singles diversion/rapid exit program.

Create a program to facilitate stays with family and friends. In fiscal year (FY) 2019, there was approximately one housing slot for every ten individuals experiencing homelessness, meaning many individuals spend years in shelters or on the streets.[41] While staying with family or friends is not always an option for returning citizens, there are steps the District can take to assist families who are willing and able to do so. The District should identify potential hosts, choosing hosts and locations that will not threaten a person’s sobriety (if applicable) or increase the likelihood of reoffending.[42] Hosts should be asked to make a commitment of at least three months. The program should offer financial assistance to the host, such as paying utility bills or providing grocery gift cards, as well as ongoing mediation to address family conflicts, particularly in the early months. Such conflicts can increase drug use and subsequent criminal activity,[43] while mediation has been shown to significantly reduce recidivism.[44] Host support groups should also be created. These groups would offer hosts an opportunity to learn from each other and make connections with others who are trying to support returning citizens.

Reconnecting with subsidized housing. Some returning citizens lived in DC Housing Authority (DCHA), Department of Human Services (DHS), or Department of Behavioral Health (DBH) subsidized housing prior to incarceration. The housing evaluation should explore whether the person can return to that housing, and then help with anything to facilitate that, such as getting an ID or getting their name added to the lease. This is critical because many returning citizens incorrectly believe their record makes them ineligible for public housing and housing voucher programs.[45] Additionally, DHS, DBH, and DCHA should look at their current requirements and see if any of them can be dropped or reduced so that more people can return to their subsidized housing.

Create medium-term housing options. Recidivism declines dramatically after three years, and recidivism is extremely low after five years of arrest-free behavior.[46] The District should create medium-term housing options that can last at least three years for returning citizens who are at high risk of recidivism. The CSOSA Auto Screener, a tool to empirically assess each person’s likelihood of future criminal behavior[47] should be part of the evaluation for allocating medium-term housing.

A promising option is a joint Transitional Housing-Rapid ReHousing (TH-RRH) program. The TH component would provide support services to meet the unique needs of returning citizens, in a communal housing setting. Because many people face struggles exiting from transitional housing to managing housing completely on their own—with many experiencing homeless,[48] DC should create a Rapid ReHousing program for some returning citizens leaving transitional housing. RRH provides a time-limited subsidy and services tied to the resident’s needs and stabilize the resident in housing that they can remain in after the subsidy and services end.

Another promising option, for returning citizens who work but need help paying rent, is the DC Flex program. This program, currently in a pilot phase, provides $7,200 a year for four years to cover rental costs, helping participants bridge the gap between their income and rental costs. If the District moves to expand DC Flex, it could create a component for returning citizens.

Expand Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) and consider prioritizing returning citizens for existing slots. PSH combines non-time limited affordable housing with intensive services for those who need it. Yet the number of slots falls short of the need so the District sets preferences for admission to the program. Returning citizens with high needs and high likelihood of recidivism should receive a preference.

Most PSH is tenant-based, meaning individuals receive subsidies to rent apartments in the community. Given the desire that most focus group respondents had to live in community with other returning citizens, the District should create PSH buildings dedicated to this population.

Dedicate shelter space specifically for returning citizens. Even with expanded services, some returning citizens will end up experiencing homelessness. Given the importance of services following release from incarceration, the District should set aside dedicated shelter space for returning citizens. These programs would ensure each new resident is met immediately by a case manager whatever the time of arrival, have low case manager to client ratios, employ staff who are specially trained in working with returning citizens, and have substance abuse and mental health treatment on site. These programs should be focused on exit planning from day one in the program. Exit planning should include housing navigators to help residents find housing, and roommate(s) if needed.

Non-Housing Services: Strengthen Mental Health Services

Housing is especially crucial for the many returning citizens who have mental health conditions. Department of Behavioral Health staff report “that people are more likely to stray from their treatment plans if they do not have stable housing.”[49] Additionally, homelessness can be a traumatic event that can exacerbate a person’s mental illness.[50] And homelessness among people with mental illness leads to more contact with the criminal justice system as well as higher rates of criminal victimization.[51] Thus, housing is considered an “evidence-based practice” in the treatment of mental health conditions.[52]

Yet as noted in this report, access to mental health services for returning citizens is limited and should be expanded.

- A DBH liaison at CSOSA receives a list of consumers who are scheduled for release in the next 120 days. They receive 35 to 50 referrals a month but are only able to prioritize 20 for connection with a Core Service Agency (CSA).[53] Additionally returning citizens have been waitlisted for services. The District should ensure all referrals are connected to a CSA and that there are not waitlists for services.

- Currently, returning citizens often are assigned to a provider haphazardly. There is no evaluation to determine which CSA would best meet the individual’s needs. And returning citizens are often assigned to CSAs that are difficult for them to get to. Instead each client’s needs should be examined, including logistical challenges, and clients should be matched based on these needs.[54]

- Under a new DBH policy, CSAs are only reimbursed for eight hours of services before release unless they complete a burdensome process to be reimbursed for more hours. This is not sufficient time to support a consumer in securing employment, housing, or disability and other benefits, leading to individuals being released before these supports are in place. DBH has not produced data to support the restriction in hours. DBH should follow the Council for Court Excellence’s (CCE’s) recommendations and produce a study on discharge service to better understand the true costs. In the meantime, DBH should eliminate the current limit.

Prepare People for Return

Steps should be taken while people are still incarcerated that would greatly increase the likelihood that they will have a successful transition.

The District should help incarcerated persons maintain relationships. Promoting family engagement while a person is incarcerated is one of the most effective best practices for reducing the risk of recidivism and increasing the likelihood that a returning citizen will receive help with housing needs.[55] Yet research finds that “visitation and phone calls are less common for individuals housed far away and with longer sentences, because of long traveling distances and the high costs of collect calls from prison.”[56] The District should offer video visitation when possible and pay for phone calls. Additionally, the District should support and supplement the current work of community groups that currently lead bus trips to five facilities.[57]

Let people serve the end of their sentences at the DC Jail. The BOP has allowed a small number of returning citizens to serve the last few months of their sentence at the DC Jail so they can connect with family, friends, and local service providers.[58] The District should offer this to all appropriate returning citizens.[59] The planning for a new jail should incorporate this function.

Connect returning citizens with local mental health, employment, and housing service providers before discharge. Focus group participants who had connected with service providers while incarcerated reported much less anxiety upon release, particularly those who had contact with a housing provider. Yet it is difficult for local service providers to connect with residents in BOP facilities because of distance and the number of facilities.[60] The District should explore ways to connect incarcerated individuals to service providers such as through video conferencing or paying for providers to travel to facilities.

Meet Returning Citizens at the prison gate if possible. Correctional workers report that retuning citizens experience “gate fever,” “anxiety and irritability at the time of release.”[61] When asked what would have been helpful in obtaining housing, 69 percent of those who had experienced homelessness stated having a prison counselor at “the moment of release.”[62] These needs and feelings are likely to be heightened for District residents housed in distant locations and who have had fewer interactions with friends and family. The District should help family, friends, or local service provider staff meet the returning citizen at prison gate. If not possible, the District could ensure someone at least can meet the returning citizen’s bus.

Encourage improvements to halfway houses. About 50 percent of returning citizens transition from a BOP facility to supervision under CSOSA through a BOP-contracted Residential Reentry Center, commonly known as halfway house. Hope Village is the current men’s halfway house and Fairview is the women’s halfway house. Unfortunately, the District has little influence on the halfway houses because they are BOP-funded.

All of the male focus group participants and all but one of the female focus group participants said that halfway house staff were generally not helpful, and none of them reported receiving help in securing housing. A MORCA staff member concurs with these reports, saying that “after [their stay] they are pretty much on their own.”[63] Additionally, DC’s Corrections Information Council has criticized Hope Village for its treatment of residents.[64] And the Council for Court Excellence, (CCE) asked the BOP not to renew Hope Village’s contract because of the poor quality of services, including housing assistance.[65]

The BOP awarded the men’s contract to a new provider, CORE DC, but Hope Village is appealing this contract decision. In the interim, its contract has been extended.[66]

Additionally, the District should encourage that the halfway houses be exit-focused, working from day one to identify possible housing options upon release, provide quality services, and partner with local nonprofits so that residents can maintain services upon release.

Employment

Making specific recommendations around how to help returning citizens get and keep employment is beyond the scope of this paper, but we recommend employment strategies be part of the needs assessment and strategic plan. The Workforce Investment and Opportunity Act (WIOA), the largest source of federal funding for workforce development efforts, requires that jurisdictions create programming that specifically meet the needs of returning citizens and those experiencing homelessness.[67] One initial step is to ensure that returning citizens are connected with these programs.

Take Full Control of Our Criminal Justice System

While it would be an expensive undertaking, taking full control of our criminal justice system would make it easier to solve many of the problems outlined in this paper. DC would create their own courts, prison, halfway houses, and parole system. The District would control prison and halfway house programming to ensure that each inmate has access to mental health services, education, employment, and housing location assistance. Both the prison and the halfway houses could partner with nonprofit organizations to provide some or all of these services, so inmates would have continuity of services and supports upon release. The prison and the halfway houses would be located in DC so families and friends could more easily visit. The prison could also coordinate release dates with openings in housing slots, creating a more seamless transition. And every person could be met at the gate upon release either by a family member/friend or by a counselor, ensuring they receive critical support in the anxious first moments after release.

Appendix 1

For this report we conducted three focus groups in winter 2018-2019. Focus groups, as a method, provide insights into how people think and provide a deeper understanding of the phenomena being studied. Our focus groups were intended to gain firsthand accounts from returning citizens.

Each focus group was coordinated with a non-profit organization that serves returning citizens. The non-profits were University Legal Services, Jubilee Housing, and Thrive DC. The groups varied in size from four individuals to over twenty participants. The groups were composed of both men and women. Their incarceration period and location varied as did their date of release from incarceration, some having been released just weeks prior. While the conversation flowed to a number of different topics, the following are the general questions that were posed to the groups:

Please tell us what name you’d like to use (a fake name is okay) and when you exited prison and/or a halfway house.

How long was your most recent period of incarceration?

Can you list the states where you were incarcerated in order, starting where you were first incarcerated?

Were you able to keep in touch with family and friends while incarcerated? If so, how did you communicate? What helped you keep in touch? What made it hard?

Were you able to stay with family or friends when you first came home? Why or why not?

Did you think about getting housing during your last three months of prison? Did anyone talk to you about it? If you went to a halfway house, did anyone there help you find or apply for housing?

Can you list the places you’ve stayed in order, starting from when you were released? And can you name the program if it was part of one? Do you think the programs were good? What made them good or bad?

How did you access these programs or know about them?

Were you denied from any programs? Were you told the reason why?

How long did you stay?

Were you terminated for any reason?

Did you feel these programs helped you have stable housing or otherwise helped you?

What kinds of help did you need but not receive?

Would a financial stipend to your family or friends allow you to live with them? Or afford your own housing? How much do you think it would need to be?

What are some possible ways the prisons, organizations, government or community can help returning citizens avoid homelessness?

Each focus group lasted approximately an hour and a half. The participants were given a gift card for their participation. The conversations from these focus groups greatly helped to inform this report.

Appendix 2

The following government agencies are responsible for homeless services and services for incarcerated people and returning citizens.

The Interagency Council on Homelessness is a local body comprised of government agencies, service providers, advocates and residents who have experienced homelessness. It informs and guides strategies and policies for meeting the needs of residents who are homeless or at imminent risk of becoming homeless. The only criminal justice government member is the Department of Corrections, which manages the DC Jail and the Correctional Detention Facility (CDF). This means that there is no government representative that represents the needs of those returning from BOP facilities.

The Department of Human Services (DHS) is the local agency that manages District-funded homeless services, including shelters, transitional housing programs, and affordable housing programs dedicated to serving homeless residents.

The Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) is a local agency that promotes the production of affordable housing, primarily through making loans and grants.

The DC Housing Authority (DCHA) is responsible for managing public housing and housing voucher programs. When vouchers have been allocated in the budget process to the Mayor’s Office on Returning Citizen Affairs (MORCA), DCHA has administered the vouchers while MORCA has chosen the recipients.

The Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA) is a federal agency that is responsible for supervised release, meaning that staff monitor the returning citizen in the community. Their mission is to reduce reoffending and keep the community safe. About 79 percent of returning citizens from the BOP are released to CSOSA supervision. CSOSA can only serve those who are released to its supervision. CSOSA is responsible for investigating a returning citizen’s home release plan and may disapprove a release plan if they feel it is inappropriate, for example if the individual plans to move in with a family member who has been convicted of a crime. One of CSOSA’s strategic goals is to “promote successful reintegration into society by linking offenders with preventive interventions to address identified behavioral health, employment and/or housing needs,”[68] but reports that “finding housing for returning offenders is one of the most difficult parts of the job.”[69]

Dually established by the DC Council and the US Congress to facilitate collaboration among local and federal partners, the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council (CJCC) is “dedicated to continually improving the administration of criminal justice” by serving as “the forum for identifying issues and their solutions, proposing actions, and facilitating cooperation that will improve public safety and the related criminal and juvenile justice services.”[70]

CJCC has an Adult Reentry Steering Committee that is tasked with developing and supporting “the implementation of a comprehensive, data-driven, District-wide three-year action plan for reentry that provides strategies for connecting returning citizens with housing” and other services.[71] Neither the Department of Human Services (DHS) nor the Interagency Council on Homelessness (ICH) are members of the Committee. The DC Housing Authority is a member, but the DC Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) is not.

The Office of Victim Services and Justice Grants (OVSJG) is a local agency that funds community-based and District agency services for victims of crime and justice-involved individuals and “coordinates efforts to provide a continuum of care for incarcerated and returning citizens.”[72] OVSJG is the State-Administering Agency (SAA) for the District, responsible for the direction of systemic criminal justice planning, coordination, management, and technical assistance. It also provides grants for reentry services and funds technical assistance to promote collaboration among reentry service providers.[73]

Finally, OVSJG funds the Reentry Action Network, a “coalition comprised of nonprofit organizations that provide direct services to returning citizens,” including housing. [74] One of their goals is to “identify gaps in services and work with government agencies to develop new services and policies.”[75]

The Mayor’s Office on Returning Citizen Affairs (MORCA) was created through local legislation to “coordinate and monitor service delivery to ex-offenders … and make recommendations to the Mayor to promote the general welfare, empowerment, and reintegration of ex-offenders in the areas of…housing” and other needs.[76] As part of their Strategic Plan, they aim to strengthen their ability to connect returning citizens to housing because clients reported this as a critical need.[77] They plan to do this through creating partnerships with housing agencies and landlords. In order to do this, they reported the need to hire a housing specialist and funding for this position was included in the FY 2020 budget.[78] It is too early to tell if one housing specialist is sufficient to meet the needs. When housing vouchers have been dedicated to returning citizens during the annual budget process, MORCA has identified the individuals to receive them.

The federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) is responsible for the correctional facilities that house individuals who are convicted of a felony and receive sentences of more than one year. It also manages the contracts of DC’s two halfway houses.

The DC Department of Corrections (DOC) “ensures public safety” and is responsible for the DC Jail, which confines pretrial individuals and those whose sentences are less than one year. Some people who are incarcerated in a BOP facility are given a chance for resentencing and move to the DC Jail. Additionally DOC is the lead partner in the READY Center.

The Department of Behavioral Health (DBH) is tasked with linking returning citizens to Core Service Agencies (CSAs), community mental health services providers.[79] These CSAs are tasked with developing a discharge plan that addresses housing and other needs. Additionally one of DBH’s strategic objectives is to “maximize housing resources and target the most vulnerable District residents with serious behavioral health challenges who are homeless, returning from institutions, or moving to more independent living to prevent and minimize homelessness.”[80] DBH administers its own housing programs to meet this objective, but the need far outweighs the available slots.

[1] Following the practice of our partner the Council for Court Excellence, DCFPI uses the phrase ‘returning citizen’ to “describe the people around whom this report centers because it is the preferred terminology in the District, as expressed by the community of people who have been directly affected by involvement with the justice system….It is a term of art chosen to express people’s desire to be fully included in the life of their community—to work, go to school, vote, serve on juries, raise their children and contribute taxes. Also, the term “returning citizen,” as used throughout this report, does not exclude people who are not U.S. citizens.” See “Beyond Second Chances: Returning Citizens’ Re-entry Struggles and Successes in the District of Columbia,” Council for Court Excellence, revised December 2016, p. v, http://www.courtexcellence.org/uploads/File/BSC-FINAL-web.pdf

[2] Maya S. Kearney, M.A.A, “Ethnographic Assessment of the DC Mayor’s Office on Returning Citizen Affairs,” The Cultural Systems Analysis Group, University of Maryland, revised 2015, p. 17.

[3] Kearney, p. 14.

[4] Marta Nelson, Perry Deess, and Charlotte Allen, “The First Month Out: Post Incarceration Experiences in New York City,” Vera Institute of Justice, revised September 1999, https://www.vera.org/downloads/Publications/the-first-month-out-post-incarceration-experiences-in-new-york-city/legacy_downloads/first_month_out.pdf

[5] This paper is limited to examining the needs of returning citizens over the age of 18 who are not immediately looking to reunite with children. This is because the District has different homeless services systems for minors, families, and individuals.

[6] Ellen McCann, Ph.D., “Ten-Year Estimate of Justice-Involved Individuals in the District of Columbia,” Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, revised September 2018, http://www.jrsa.org/pubs/sac-digest/vol-29/dc-est-just-involved.pdf

[7] Nazgol Ghandnoosh, Ph.D., “Black Lives Matter: Eliminating Racial Inequity in the Criminal Justice System,” The Sentencing Project, revised 2015, https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/black-lives-matter-eliminating-racial-inequity-in-the-criminal-justice-system/ p. 6.

[8] Ghandnoosh, p.11.

[9] “Race and Criminal Justice,” American Civil Liberties Union, https://www.aclu.org/issues/racial-justice/race-and-criminal-justice

[10] McCann.

[11] “Beyond Second Chances: Returning Citizens’ Re-entry Struggles and Successes in the District of Columbia,” Council for Court Excellence, revised December 2016, p. v, http://www.courtexcellence.org/uploads/File/BSC-FINAL-web.pdf

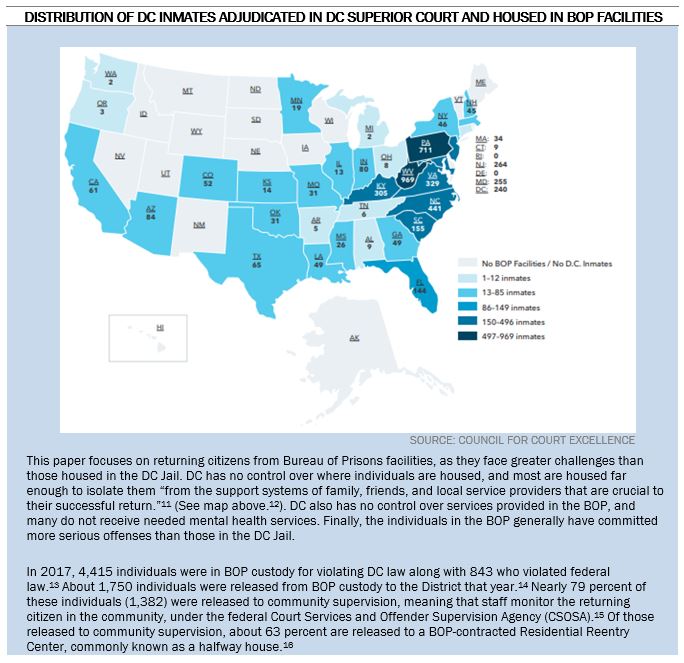

[12]“Beyond Second Chances: Returning Citizens’ Re-entry Struggles and Successes in the District of Columbia.” [13] McCann.

[14] McCann.

[15] McCann.

[16] “Beyond Second Chances: Returning Citizens’ Re-entry Struggles and Successes in the District of Columbia.”

[17] Nina Rodriguez and Brenner Brown, “Preventing Homelessness Among People Leaving Prison,” The Vera Institute of Justice, revised December 2003, https://www.vera.org/downloads/Publications/preventing-homelessness-among-people-leaving-prison/legacy_downloads/IIB_Homelessness.pdf

[18] Data from CSOSA, which serves about half of individuals returning from the BOP. The Council for Court Excellence reports that “while people under CSOSA supervision do not represent the entire returning population, the data shed light on the challenges returning citizens are likely to face,” from“Beyond Second Chances: Returning Citizens’ Re-entry Struggles and Successes in the District of Columbia.”

[19] Andrew Aurand, Ph.D., MSW, Dan Emmanuel, MSW, et al., “Out of Reach: the High Cost of Housing,” National Low Income Housing Coalition, revised 2018, https://reports.nlihc.org/sites/default/files/oor/OOR_2018.pdf

[20] Aurand, Emmanuel, et al.

[21] This includes all individuals who were assigned to CSOSA custody including those who did not go to a BOP facility but were instead given probation.

[22] “Beyond Second Chances: Returning Citizens’ Re-entry Struggles and Successes in the District of Columbia.”

[23] “Homelessness and Mental Illness: A Challenge to Our Society,” Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, revised November 18, 2018, https://www.bbrfoundation.org/blog/homelessness-and-mental-illness-challenge-our-society

[24] Christie Thompson and Taylor Elizabeth Eldridge, “Treatment Denied: The Mental Health Crisis in Federal Prisons,” revised November 21, 2018, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2018/11/21/treatment-denied-the-mental-health-crisis-in-federal-prisons

[25] Thompson and Eldridge.

[26] Thompson and Eldridge.

[27] Wendy Sawyer, “How much do incarcerated people earn in each state?” Prison Policy Initiative, revised April 10, 2017, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/wage_policies.html

[28] “Beyond Second Chances.”

[29] “Beyond Second Chances.”

[30] Stephen Metraux, PhD, Caterina Roman, PhD, and Richard Cho, MCP, “Incarceration and Homelessness,” revised March 2017, https://www.huduser.gov/portal//publications/pdf/p9.pdf

[31] Metraux, Roman, and Cho.

[32] Conversation with MORCA staff, May 2019.

[33] Rodriguez and Brown, p. 3.

[34] Benjamin Moser, Emily Tatro, et al., “Improving Mental Health Services and Outcomes for All: The D.C. Department of Behavioral Health and the Justice System,” Office of the District of Columbia Auditor, revised 2018, http://zd4l62ki6k620lqb52h9ldm1.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/DBH.Report.2.26.18.pdf

[35] Moser, Tatro, et al., p. 73.

[36] Moser, Tatro, et al., p. 119.

[37] Bill Kuennen and Dominique Vinson “FY 19/20 Project Reconnect: Diversion/Rapid Exit Pre-Application Conference” Department of Human Services, revised October 12, 2018.

[38] “Mayor Bowser Launches the READY Center, Connecting Retuning Citizens To Housing, Employment, and Other Critical Programs,” Office of the Mayor, revised February 12, 2019, https://mayor.dc.gov/release/mayor-bowser-launches-ready-center-connecting-returning-citizens-housing-employment-and

[39] “Mayor Bowser Expands READY Center Services to Retuning Citizens from the Federal Bureau of Prisons,” Office of the Mayor, revised April 12, 2019, https://mayor.dc.gov/release/mayor-bowser-expands-ready-center-services-returning-citizens-federal-bureau-prisons

[40] “CJCC Strategic Priorities and Associated Committees and Workgroups,” Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, https://cjcc.dc.gov/page/cjcc-strategic-priorities-and-associated-committees

[41] Morgan Baskin, “By Some Metrics, the Number of People Facing Housing Instability in D.C. Continues to Grow,” Washington City Paper, June 5, 2019, https://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/news/housing-complex/article/21071867/by-some-metrics-the-number-of-people-facing-housing-instability-in-dc-continues-to-grow

[42] If the returning citizen will be released on a parole, their parole officer should join the assessment to ensure that the host meets parole requirements. For example, a returning citizen may not be allowed to return to a spouse who took part in their criminal activities or to a home that is already hosting someone on parole.

[43] Shawn M. Flower, Ph.D., “Final Report: District of Columbia Custodial Population Study: Seeking Alignment between Evidence Based Practices and Jail Based Reentry Services,” The Moss Group, Inc., revised September 2017,

[44] Flower.

[45] Katharine H. Bradley, R.B. Michael Oliver et al., “No Place Like Home: Housing and the Ex-prisoner,” Community Resources for Justice, revised November 2001, https://www.cjinstitute.org/assets/sites/2/2001/05/54_No_Place_Like_Home.pdf

[46] Joan Petersilia, “Hard time: ex-offenders returning home after prison,” Corrections Today, April 1, 2005.

[47] “Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency for the District of Columbia: Strategic Plan for Fiscal Years 2018-2022,” https://www.csosa.gov/wp-content/uploads/bsk-pdf-manager/2019/02/CSOSA-Strategic-Plan-FY2018-2022.pdf

[48] “Homeward DC: District of Columbia Interagency Council on Homelessness Strategic Plan 2015-2020,” https://ich.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ich/page_content/attachments/ICH-StratPlan2.7-Web.pdf p. 27.

[49] Moser, Tatro, et al., p. 80.

[50] “Homelessness and Mental Illness: A Challenge to Our Society.”

[51] “Homelessness and Mental Illness: A Challenge to Our Society.”

[52] Moser, Tatro, et al., p. 83.

[53] Moser, Tatro, et al.

[54] Moser, Tatro, et al.

[55] Metraux, Roman, and Cho; Jeremy Travis, Amy L. Soloman, and Michelle Waul, “From Prison to Home: The Dimensions and Consequences of Prisoner Reentry,” Urban Institute, revised June 2001, http://research.urban.org/UploadedPDF/from_prison_to_home.pdf

[56] Kearney, p. 16.

[57] “Using this book,” Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency for the District of Columbia, www.csosa.gov/wp-content/uploads/bsk-pdf-manager/2018/03/families_first.pdf

[58] “Beyond Second Chances: Returning Citizens’ Re-entry Struggles and Successes in the District of Columbia.”

[59] Some individuals cannot be housed at the Jail because it lacks the appropriate level of security and supervision.

[60] Kearney.

[61] Travis, Soloman, and Waul.

[62] Bradley, Oliver et al., p.7.

[63] Kearney, p. 19.

[64] “Memo RE: RFP-200-1270-ES for Residential Reentry Center and Home Confinement Services,” DC Corrections Information Council, revised September 7, 2016, https://cic.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/cic/page_content

/attachments/CIC%20letter%20to%20BOP%20re%20RRC%20RFP%209%208%2016.pdf

[65] “Beyond Second Chances: Returning Citizens’ Re-entry Struggles and Successes in the District of Columbia.”

[66] The contract with CORE DC is also at risk as they lost the lease on the DC building they intended to use. They are currently petitioning to be given more time to find a new building. If Hope Village or CORE DC do not prevail, DC’s retuning citizens will be sent to halfway houses as far away as Wilmington, Delaware; Norfolk, Virginia; and Baltimore, Maryland. This distance will make it more difficult for residents to maintain relationships and find employment in DC. It also means that people will have to recertify for DC’s public benefits and services upon release from the halfway house, meaning residents will likely have a gap in benefits. If this occurs, the Mayor and Council should try to work with the BOP to see if they would be willing to issue a new request for proposals or consider using a District-funded halfway house.

[67] “The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act: What Corrections and Reentry Agencies Need to Know,” The National Reentry Resource Center, revised May 2017, https://csgjusticecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/6.13.17_WIOA_What-Corrections-and-Reentry-Agencies-Need-to-Know.pdf