DC’s Chief Financial Officer (CFO) Glen Lee overstepped his authority by forcing the mayor to replenish reserves more quickly than what DC law requires, blowing a $253.6 million hole in her forthcoming budget. This will force cuts in essential services in a budget that already is expected to include deep cuts to address a $900 million gap. Lee’s choice to go beyond the law will have real-world impacts, such as a potential steep cut in the mayor’s budget for pay for early education teachers and aides, a low-paid and mostly Black and brown workforce, insiders report. This clear case of overreach—lawmakers set the budget, not the CFO—is denying Mayor Bowser an opportunity to meet the needs of DC’s most underserved communities and residents in a particularly tight budget year.

Lee’s claim that replenishing DC’s reserves by fiscal year 2025 is necessary to shape a “financially sound” budget is weak. Today, DC’s reserves are over $1.5 billion and are at nearly 85 percent of maximum capacity. In addition, fiscal policy analysts such as bond rating agencies don’t expect jurisdictions to increase reserves when budgets are out of balance, as is the case today in many cities and states. The reserve in question is replenished when DC has budget surpluses, a common-sense approach. Lee’s position is also shortsighted because it ignores the economic harms that come from cutting public investments in critical government services, such as affordable, quality child care or public transportation.

The mayor and DC Council should hold their ground and clarify in their budget proposals, specifically through the Budget Support Act, that they have the authority to replenish the reserves using future budget surpluses. In turn, the CFO should stop holding the budget process hostage and drop his refusal to certify the budget based on this policy alone. Lawmakers should also pair this strategy with efforts to tax DC’s outsized wealth to meet the moment and pass an equitable budget.

A Shorter Repayment Timeline Hurts Us All, Puts Equity At Risk

Every dollar that DC must use to replenish the reserve earlier than what is legally required is one lawmakers don’t have to help residents afford rent and put food on the table. Prudent fiscal policy is to replenish reserves only when finances are strong. Yet, the February forecast bleakly demonstrated that DC’s revenues are growing too slowly to keep up with the costs of providing current investments, not to mention growing needs, according to DCFPI’s analysis. This coincides with a reported $900 million in budget pressures that lawmakers must also address in the upcoming budget, in part due to expiring federal pandemic aid, a transit budget deficit, and anticipated updates to collective bargaining agreements.

The Pay Equity Fund (PEF) appears to be the program most at risk of being cut to accommodate the CFO’s demands, according to Washington City Paper. The PEF, which launched in 2022, has boosted pay for more than 4,000 early educators and financed affordable health insurance for over 1,000 of these workers’ families. This program is disrupting the pervasive and centuries-long undervaluing of caregiving that has, due to structural racism and sexism, disproportionately harmed Black and brown women. Lawmakers already cut the program in the current budget, and the fund itself is also facing its own growing budget pressures and wouldn’t be able to absorb further cuts without harming educators.

DC’s Reserves Are Already Mostly Full and Poorly Designed for Hard Economic Times

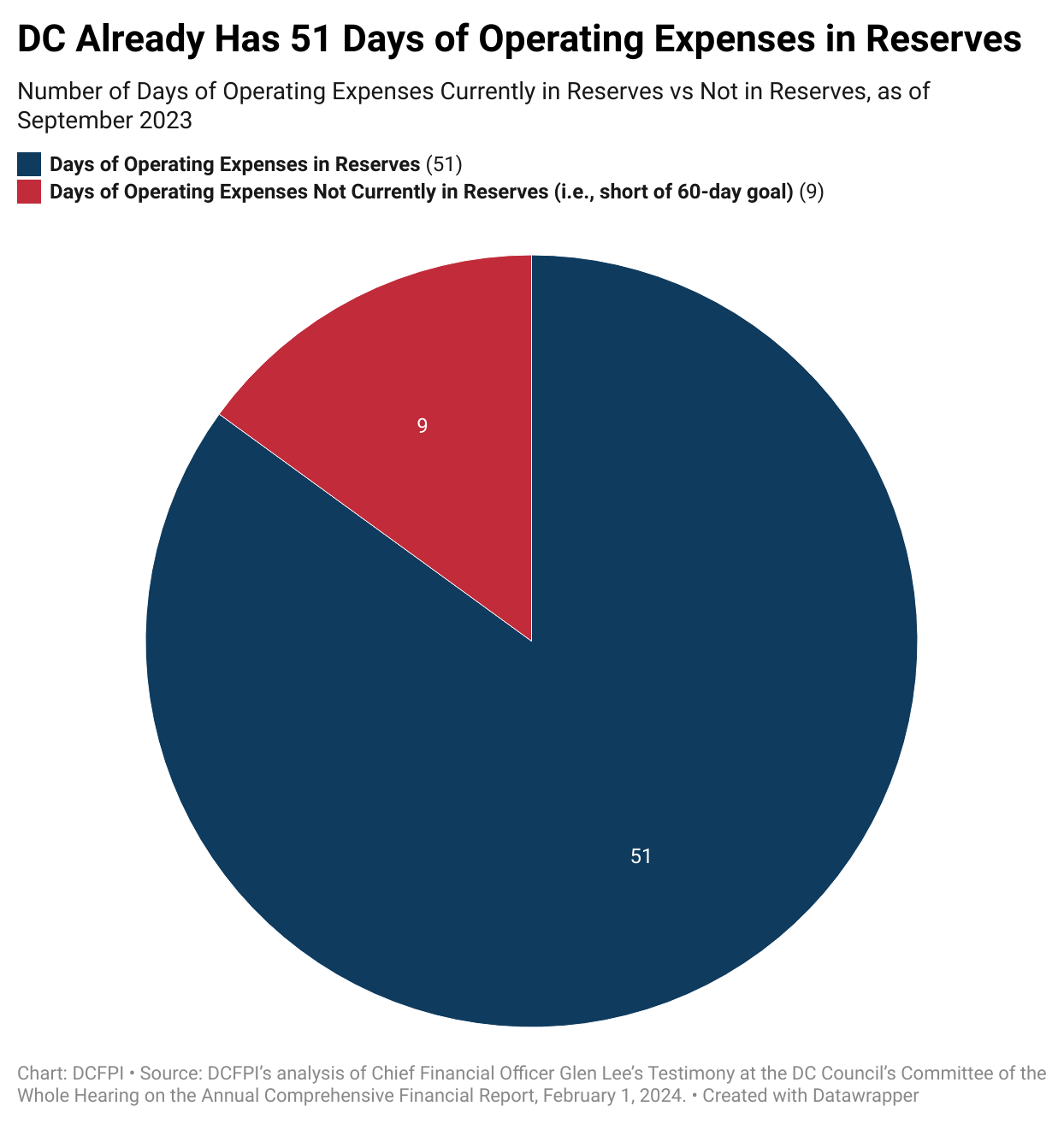

The dispute between the CFO and lawmakers centers primarily on a largely tapped Fiscal Stabilization Reserve Fund (FSRF), one of DC’s four reserves, which are aimed at managing cash-flow needs and weathering economic downturns. The FSRF has the lowest funding of the four, reflecting the fact that it is the only reserve that works as a flexible rainy day fund. The other reserves are overly restrictive. But looking at the four reserves together—the best way to assess the health of our financial cushion— DC is currently meeting 85 percent of its savings goal, or 51 of 60 days of operating expenses in reserve (Figure 1). The 60-day standard is from the Government Finance Officers Association and is intended to encourage states and cities to build up reserves that can be drawn down when needed. DC, in fact, has more days of reserves on hand than the 2023 median for the 50 states, which was 46 days.

Lawmakers wisely leveraged the FRSF in the fiscal year (FY) 2021 budget with a plan to repay it with future surpluses and other revenue over four years, which the then-CFO certified as fiscally sound. Lee is now refusing to follow the law and this precedent as lawmakers seek to replenish the FRSF after using it in the FY 2024 budget. He is demanding that lawmakers speed up the timeline for refilling the FRSF, even though there wasn’t a large enough end-of-year FY 2023 surplus to fully replenish the reserve.

There’s No Proof that Following the Law Will Hurt DC’s Bond Rating

The CFO expressed fear that creditors will downgrade the District’s bond rating if lawmakers don’t quickly rebuild its reserves to 60 days, according to news reports, but that is an overly cautious take. Building up rainy day reserves—and using them during hard times—is indeed smart financial management, because it helps limit budget cuts or tax increases when the economy is weak. This is what lawmakers are doing, and with reserves funded at 85 percent of full capacity and no plans to reduce them, DC’s reserves management should not be viewed as anything but fiscally sound.

Moreover, cities and states that tap their reserves responsibly have been able to protect their bond rating: 40 states used rainy day reserves in the Great Recession, and 35 kept their bond ratings intact, for example, as DCFPI previously reported. DC already has the highest possible credit rating for all outstanding General Obligation Bonds, and it is unlikely that responsibility repaying the FSRF over the financial plan would have a long-term negative impact on DC’s ratings.