People of color—longtime Black residents, immigrant families, and others—have built this city, shaped its culture, and made significant contributions to the economy. At the same time, decades of systemic racism created barriers that blocked Black residents from homeownership, job opportunities, quality education, and health care, and are still evident today in our affordable housing challenges, income disparities, distressing educational differences, and health outcomes. As DC is changing, its prosperity is not reaching many lower-income, Black, long-time residents, and the rising cost of living means that many cannot afford to stay here.[1]

The budget presents an opportunity each year to work toward our shared responsibility to right these wrongs and shift the District further towards an equitable future. Budgets have the power to help us create a future where no resident has to choose between paying rent and other necessities; where all students, regardless of their family’s income and the part of the city they live in, have the resources they need to succeed; where public safety emphasizes prevention over criminalization; and where all residents have access to quality, affordable health care.

While the District has continued to make progress towards investments that help residents thrive, examining the proposed fiscal year (FY) 2020 budget through a racial equity lens allows us to see the budget in a different way, highlighting missing pieces that may not be evident otherwise. This lens can tell us who is—and isn’t—benefitting from the District’s current investments, and identifies some steps the District can take now, in the FY 2020 budget, towards a more equitable DC.

The District is already taking steps to improve racial equity through policymaking. This week, the DC Council is considering the Racial Equity Achieves Results Amendment Act (REAR Act), which would implement a tool to “[eliminate] disparities based on race,” add racial equity performance measures to agency performance plans, and require District employees to receive racial equity training, among other things.[2]

Addressing decades of systemic discrimination and barriers takes a lot of time and work. It is not done in just one budget cycle or through the passage of one bill. But the FY 2020 budget, as well as the REAR Act, provide opportunities to take meaningful steps towards addressing these historic and ongoing injustices.

Education Equity Demands Increased Resources in Communities that Have Faced Divestment

Due to a long history of legal school segregation and unjust funding by race—DC was part of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case—the DC public education system is riddled with racial inequities. Across DC Public Schools (DCPS) and public charter schools, over 80 percent of white students are considered college and career ready in English, compared to 32 percent of Latinx students and 25 percent of Black students.[3] The predominately white and affluent Wards 2 and 3 comprise only 8 percent of public school enrollment, yet are home to half of the top 10 most sought-after public schools in the DC lottery.[4], [5], [6] These schools are inaccessible to many Black families due to policies that led to residential segregation. As a result, nearly half of students enrolled in public schools live in Wards 7 and 8, which are predominantly Black.[7]

A key to addressing these historical inequities is to intentionally provide more financial resources for students attending schools in areas of the District that traditionally faced divestment. Yet the way that DCPS allocates funds among schools is leading to cuts at these schools. On the surface, the formula—which primarily relies on enrollment—appears to treat all schools equally. However, enrollment declines are primarily occurring in low-income communities of color—often due to the rise in DCPS magnet schools and public charter schools—which means those neighborhood schools routinely face resource cuts that can lose a bulk of their funding. Neighborhood schools are the foundation of our school system, since students aren’t guaranteed a spot in charters or magnets.

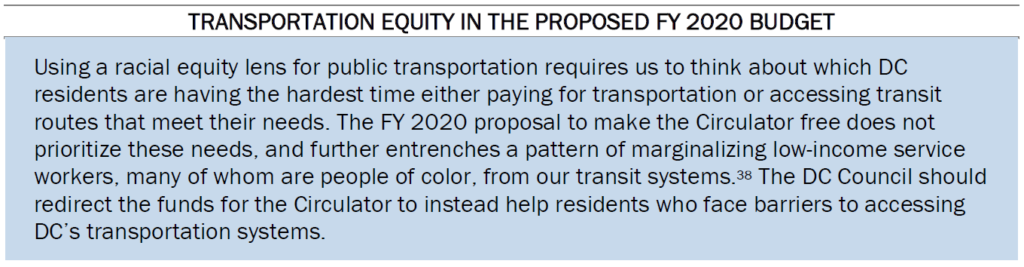

Next school year, 85 percent of the schools with proposed budget cuts of 5 percent or more are located in Ward 7 or 8 (Table 1). Budget cuts lead to cuts in staffing or services that can then lead to further enrollment declines. This outcome shows that the seemingly neutral allocation system is contributing to inequity and should be reconsidered.[8]

Furthermore, the District is not abiding by requirements to devote more funds for low-income students and others at-risk of falling behind. DC’s per-student funding formula (UPSFF) provides more resources for students who are at risk of academic failure,[9] but the funding is 40 percent below the recommended level.[10] Beyond that, DCPS knowingly diverts half of the “at-risk” funding to pay for core classroom staff, so that it’s not available for supplemental services as intended. Students in DCPS who are considered “at-risk” are consistently shortchanged.

Future school funding decisions should be rooted in equity. Treating everyone the same—what some call equality—ignores the need to focus on communities facing the greatest barriers. The process DCPS uses to allocate funds among its schools should focus on need, not simply on enrollment, and should not lead to deep cuts in schools that are predominantly Black and low-income. The District also should fully support at-risk funds and stop the practice of diverting these resources, to ensure they are getting to the intended students.

Health Equity Demands Eliminating Health Care Access Barriers Imposed on Immigrants

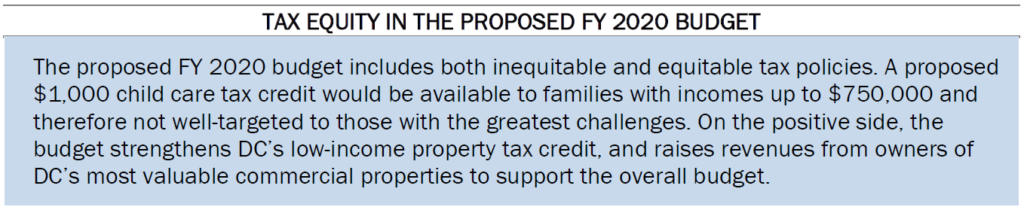

In 2011, DC implemented a new rule requiring participants to visit a DC social service center every six months to maintain their eligibility, rather than an annual recertification process that most DC benefit programs have.[11] This stringent requirement led to a sharp drop in the number of residents getting health coverage through the Alliance (Figure 1). This is comparable to requiring all residents to visit the DMV in person every six months to keep a driver’s license.

This six-month recertification policy is a barrier that prevents individuals from accessing care. Because of the intensive recertification process, many Alliance participants face a lapse in coverage, meaning they have intermittent coverage and only return to the Alliance when they are in immediate need of medical care. The high rate of “churn” in the Alliance is a key reason the program’s cost to the city has increased sharply, even while people are losing coverage. The six-month recertification also contributes to long lines at DC’s social service centers, affecting all residents seeking assistance by creating backlogs and increasing the chance that applications aren’t processed.

DC prides itself on being a sanctuary city that stands up for immigrants, but the continued support for a policy that targets immigrants and denies them access to health care shows that as a city we are not living up to those values.

The DC Council passed legislation to eliminate this unequal treatment in the Alliance and return to a 12-month recertification, but funding has not been provided to support the anticipated participation increase. The District should find the resources to implement these changes and ensure that all DC residents have access to health care, regardless of their immigration status.

Housing Equity Demands Investments that Prioritize Residents Most at Risk of Displacement

The inequalities we see today are the direct result of decades of compounding housing policies that have been as advantageous for white households as they have been detrimental to Black households. These include restrictive deed covenants that barred Black residents from owning land, “urban renewal” projects that displaced Black businesses and residents, and systemic housing discrimination that has undervalued homes in majority-Black neighborhoods.[13],[14] As recently as the early 2000s, Black and Latinx residents were two to three times more likely to receive subprime loans than white residents.[15]

This history has shaped today’s realities. Not only are white households far more likely to own homes compared to Black and Latinx households, the typical home value for Black homeowners is only two-thirds of the home value for white homeowners.[16] Further, nearly 90 percent of the 27,000 extremely low-income households that spend at least half their income on housing are households of color and primarily Black.[17]

The “Workforce Housing” program in the proposed FY 2020 budget would support development of housing for families earning between 60 and 120 percent of the area median income, or up to $140,000 for a family of four. Given that the Black median household income is approximately $42,000, the program will exclude most Black District residents. While Asian and Latinx households are more likely to benefit than Black households (with median household incomes respectively at $96,394 and $84,728), the program will primarily benefit white households whose median household income is far higher at $134,000.

The term “Workforce Housing” itself has classist implications about the type of work that counts as part of the “workforce.” The most common service-sector jobs—waiters/ waitresses, home health aides, cashiers etc.— pay between $20,000 and $40,000 and disproportionately are held by Black and Latinx residents.[18] The budget proposal shows a priority for a privileged group of workers and excludes other, less privileged workers (Figure 2).

In contrast to this “Workforce Housing” investment, the proposed budget provides no new assistance for the approximately 40,000 families on the DC Housing Authority waiting list, for tenant-based vouchers through the Local Rent Supplement Program (LRSP).

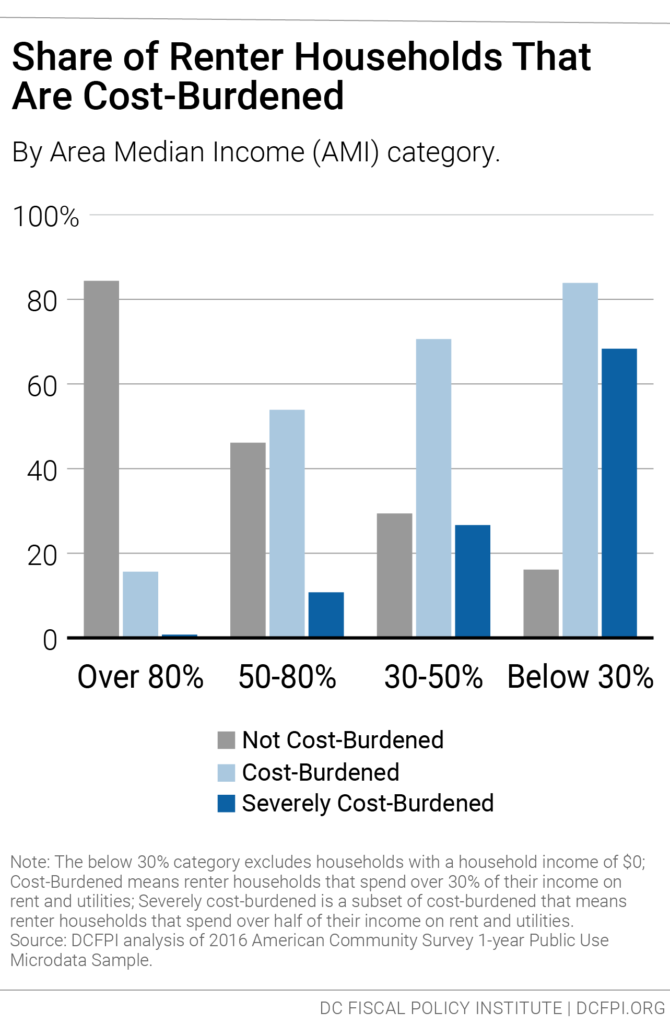

Renters in DC are almost twice as likely to be housing cost-burdened (meaning they pay 30 percent or more of their income on housing and utilities) than homeowners. Since households of color have been historically denied access to homeownership, DC’s exorbitant rents disproportionately impact communities of color. Increasing both the value and availability of tenant-based vouchers would allow low-income Black families to access high-opportunity neighborhoods throughout the District.

Additionally, the Mayor’s proposed budget did not include any funding for public housing repairs, despite the fact that public housing remains one of the few truly affordable and secure options for households experiencing deep poverty. In the District, about 7,300 families live in public housing developments managed by the DC Housing Authority.[19] DCHA has stated that given the housing stock’s severely distressed conditions, at least 2,500 units will have to be “repositioned” or outsourced to the private sector.

Past efforts to redevelop traditional public housing through HOPE VI and early New Communities Initiative efforts have resulted in the displacement of Black communities.[20],[21],[22] Choosing not to allocate funds for public housing repairs not only exacerbates the poor physical and environmental conditions at many DCHA properties, it also increases the likelihood that the District will resort to privatizing some public housing and jeopardize housing stability for countless public housing residents.

The District has the resources to make sweeping investments in LRSP and public housing that will benefit families who need it most and have been excluded from the District’s increasing prosperity. Councilmembers should choose this path as they continue to work on the FY 2020 budget.

Public Safety Equity Demands Investments to Community Approaches, Not More Policing

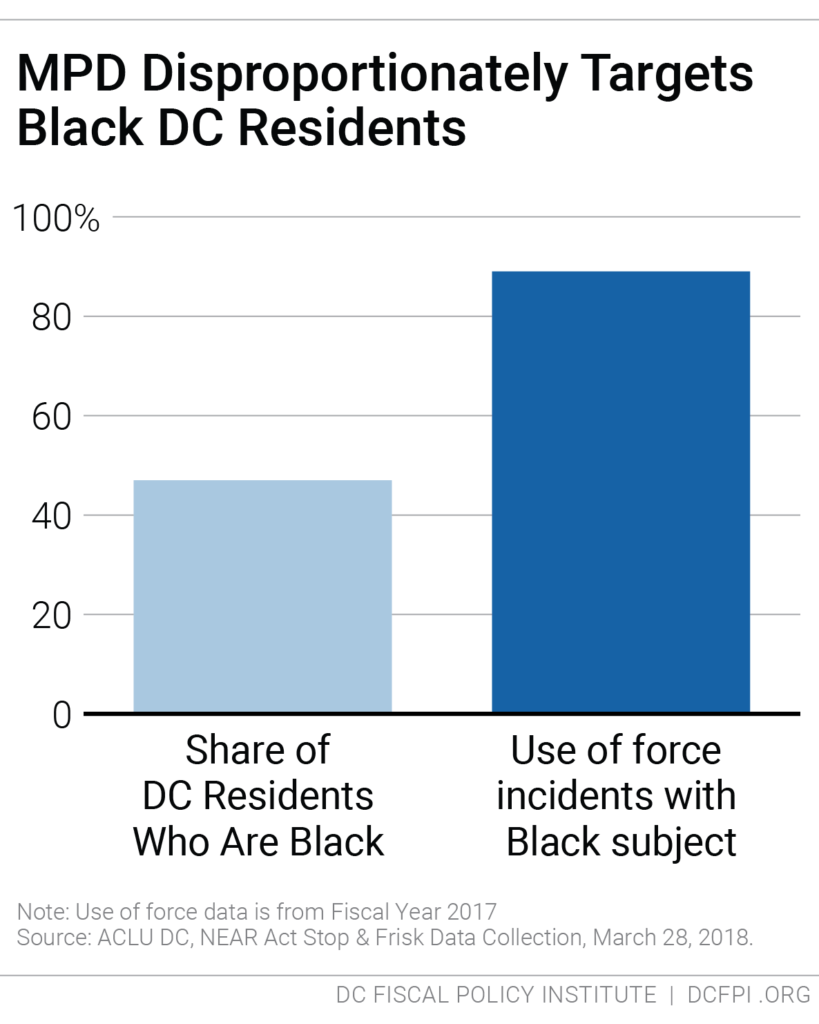

Black residents are criminalized at a significantly higher rate than other residents. Although they make up 47 percent of the DC population, roughly 80 percent of police stops,[23] 83 percent of all stop and frisks,[24] and 89 percent of reported use of force incidents involve a Black subject (Figure 3).[25] The status quo of solely relying on policing for public safety upholds longstanding patterns of criminalizing, incarcerating, and marginalizing Black residents and communities.

The Neighborhood Engagement Achieves Results Act (NEAR Act) takes a different approach to public safety, seeking to address the root causes of crime from a public health perspective by focusing on prevention, diversion, and treatment.[26] Key components of the NEAR Act include placing “violence interrupters”[27] in communities to build relationships and engage individuals at risk of being involved in violent crime;[28] similarly trained professionals at hospitals to engage community members after a traumatic event; mentorship and job training programs; and data collection on stop and frisk and use of force from DC’s police department, MPD.

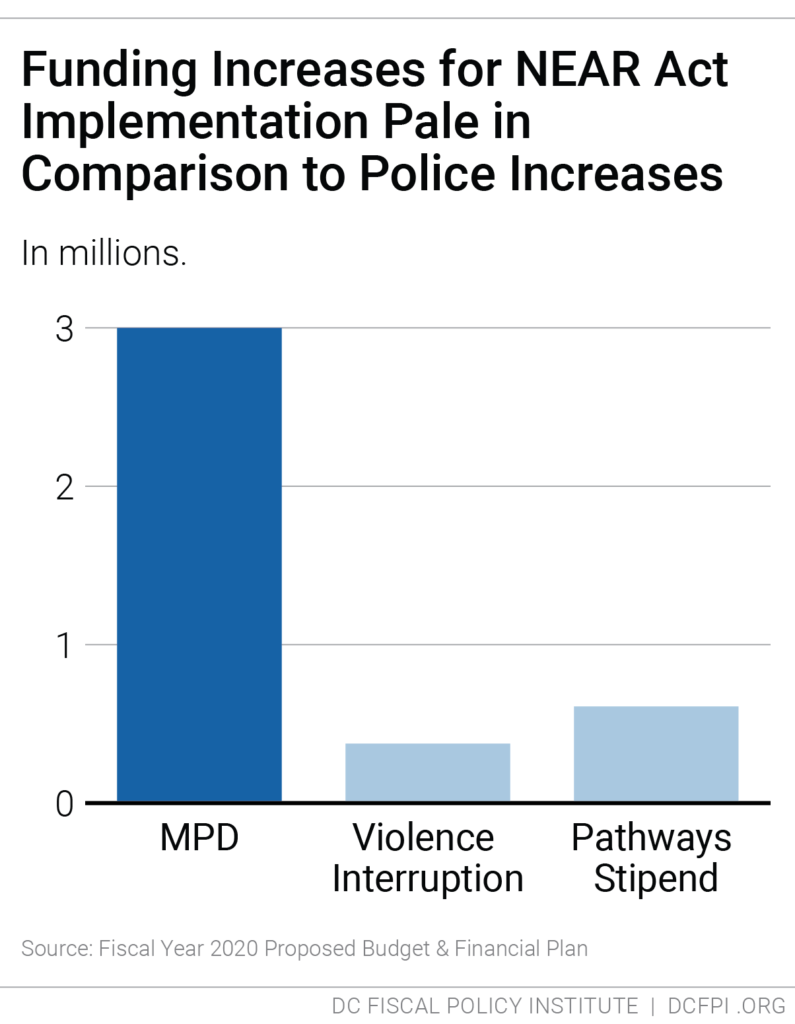

The Mayor’s proposed FY 2020 budget includes $3 million to add additional officers to MPD, on top of MPD’s existing annual $550 million budget.[29] This increase is part of an effort to bring the police force to 4,000 officers by 2021,[30] with additional funding increases expected in future years.[31] This reflects a long-standing belief that DC’s public safety depends on having a large police force—4,000 officers or more—despite the fact that DC is already among the most policed city in the U.S.[32] Meanwhile more police increases the likelihood that Black residents will have negative police interactions.

At the same time, the proposed budget makes only small increases towards further implementing the NEAR Act (Figure 4). This includes funds to increase the participant stipend through the Pathways program, which works to engage individuals at risk of crime involvement in mentorship and job opportunities ($610,000) and funds for seven additional violence interrupters and two additional case managers ($375,000).[33]

The Mayor’s budget also diverted revenue from sports betting—which under a law passed last year is intended to go towards violence interruption and investments in early childhood development—to DC’s general fund,[34] which removes a source of ongoing funding for these areas.

The proposed funding for components of the NEAR Act is far from meeting the need. While there are currently violence interrupters in 21 neighborhoods, many more communities need their services.

It’s also worth noting that MPD has failed to properly implement data collection on stop and frisk and use of force policies and practices, which are elements of the NEAR Act that have already been funded.[35] Viewed through a racial equity lens, this doubling down on a policing approach to public safety is particularly troubling, given that MPD is undermining elements of the NEAR Act. Before adding more officers, DC needs to closely examine how officers are being used now; however, this cannot happen without the necessary data collection.

Taking a racial equity approach to public safety in the FY 2020 budget means increasing funds for NEAR Act implementation and taking steps to increase police accountability and transparency. The District could redirect funds to increase MPD officers to instead fund more violence interrupters for communities that would benefit most from their presence. Simply re-directing these funds could add roughly 70 additional violence interrupters and case workers to DC communities that need them the most. Addressing the root causes of community violence also includes funding the building blocks that all people need to live healthy, successful lives—housing, schools, early childhood development, health care, and more.

Transportation Equity Demands Targeting Investments to Residents Who Current Systems Leave Behind

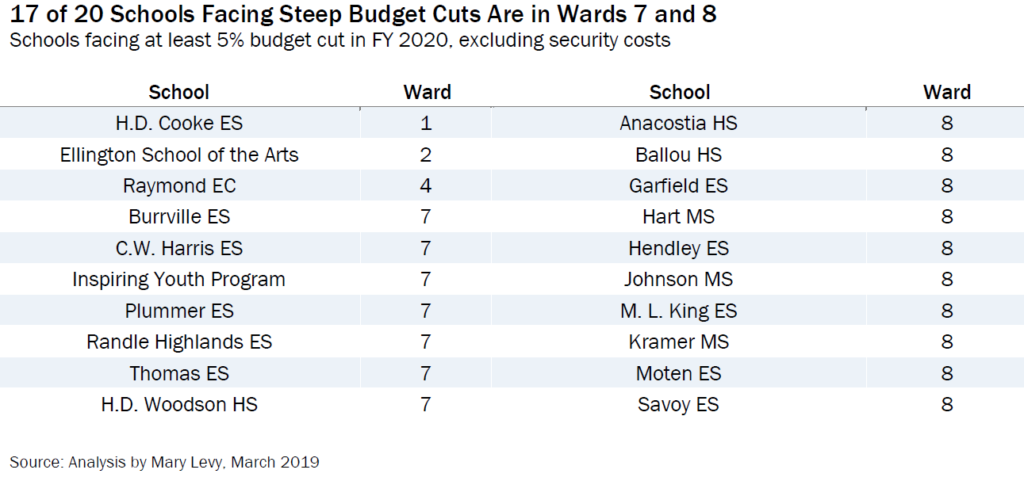

The combination of rising fares, limited operating hours, rising cost of living, and displacement increasingly creates barriers to accessing public transportation for residents with lower incomes in the District.[36] Furthermore, people with low incomes often have limited access to public transportation, because places with fewer transit options are often more affordable. Living further from public transportation means more time and money spent commuting to and from work.[37]

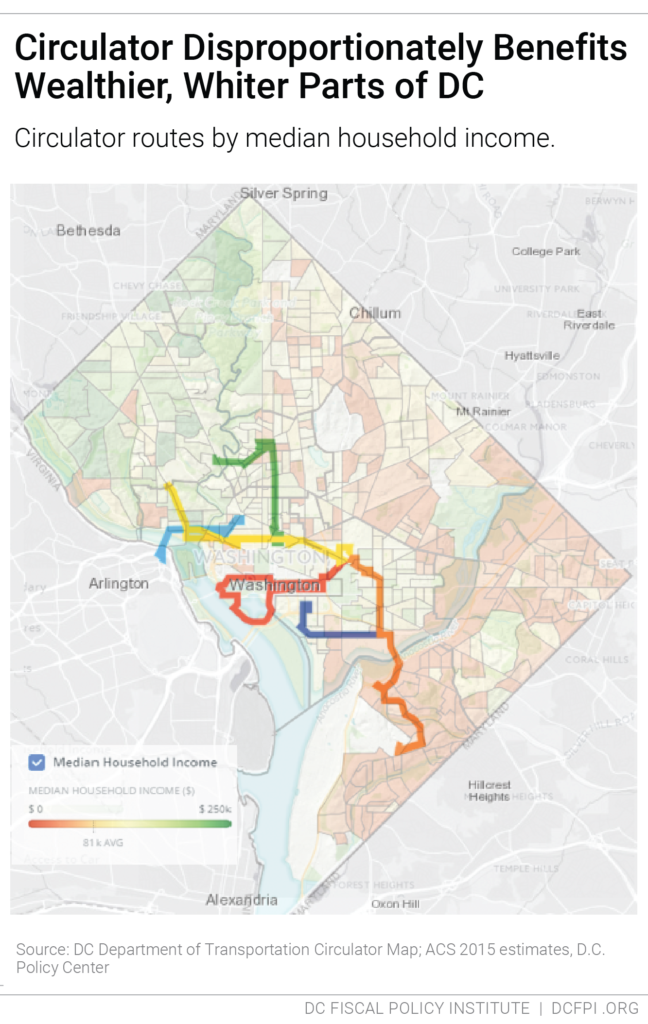

While the proposal to make the Circulator, DC’s standalone bus system, free of charge would help some residents in these circumstances, overall it prioritizes residents who are likely facing significantly fewer barriers to accessing transit in DC. Focusing on transportation equity means investing in the transit needs of lower-income residents with limited access to transportation.

The Circulator currently serves a relatively privileged group of DC residents that is whiter and wealthier than the District as a whole (Figure 5).[39] The median income of the Census tracts served is higher than the District’s median income. And the average Census tract served is 59 percent white while the District’s population is 41 percent white. Adding a route in Ward 7 will bring the average census tract served closer to the District’s overall population but the effect is likely small.[40]

Additionally, a 2019 report found that fast, reliable service is more important to low-income riders than lowering fares.[41]

The proposal to make the Circulator free should be rejected. If the District wants to subsidize fares for those most in need, it would do better to subsidize riders on Metrobus routes that serve lower income neighborhoods, or work to improve service in these communities.

Tax Equity Demands Smart Choices for a Fairer Tax Code

Creating a fairer tax system is one of the most effective tools District lawmakers have for improving racial equity. Tax policies have long been used to advantage affluent, predominantly white residents and have disparately harmed lower-income residents and communities of color.[42] For example, many states created limits on property taxes intended to protect white property owners.[43] Major provisions of the federal tax code, including taxing income from capital gains at lower rates than income from wages, and the home mortgage interest deduction, reinforce wealth inequities created by systemic racism. Recent federal tax cuts heavily favored higher-income households, who are disproportionately white.[44]

The tax code can be a powerful tool to promote racial equity.[45] This can be accomplished by designing taxes so that households with higher incomes pay a larger share of their income in taxes than lower-income households do. States can take steps such as strengthening their income taxes, better taxing wealth, and enacting or expanding tax credits for low-income families to create a fairer tax code. While the District has done a good job decreasing taxes for DC’s lowest-income residents, middle-income residents still pay a slightly larger share of their income than the top 1 percent. [46]

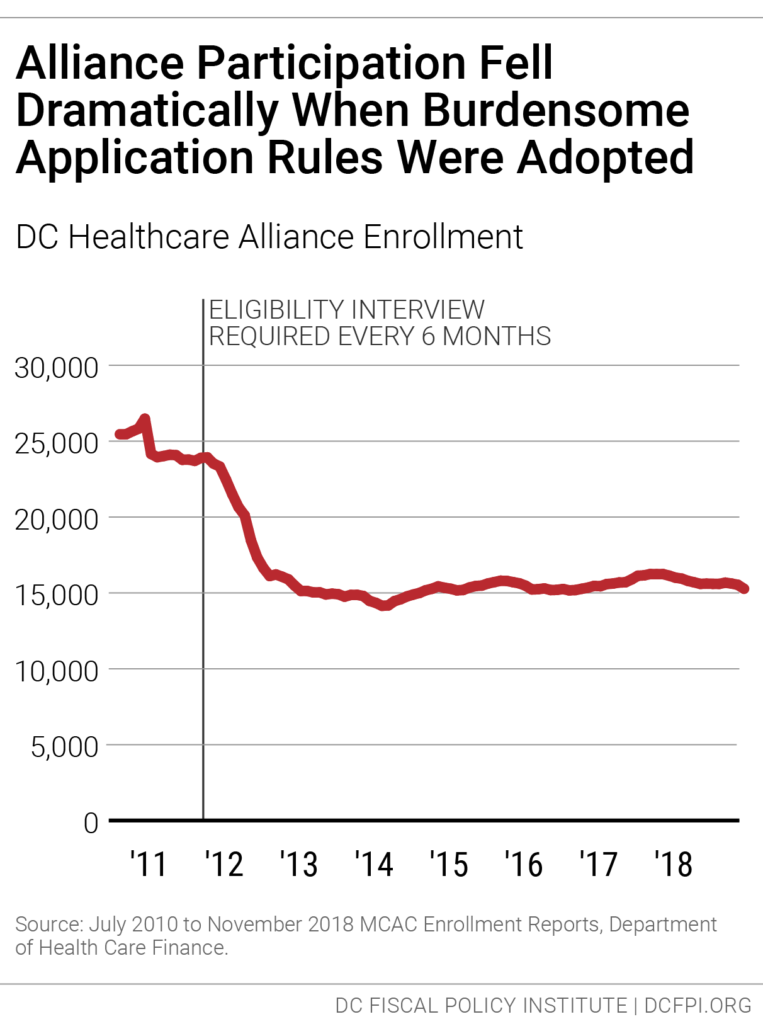

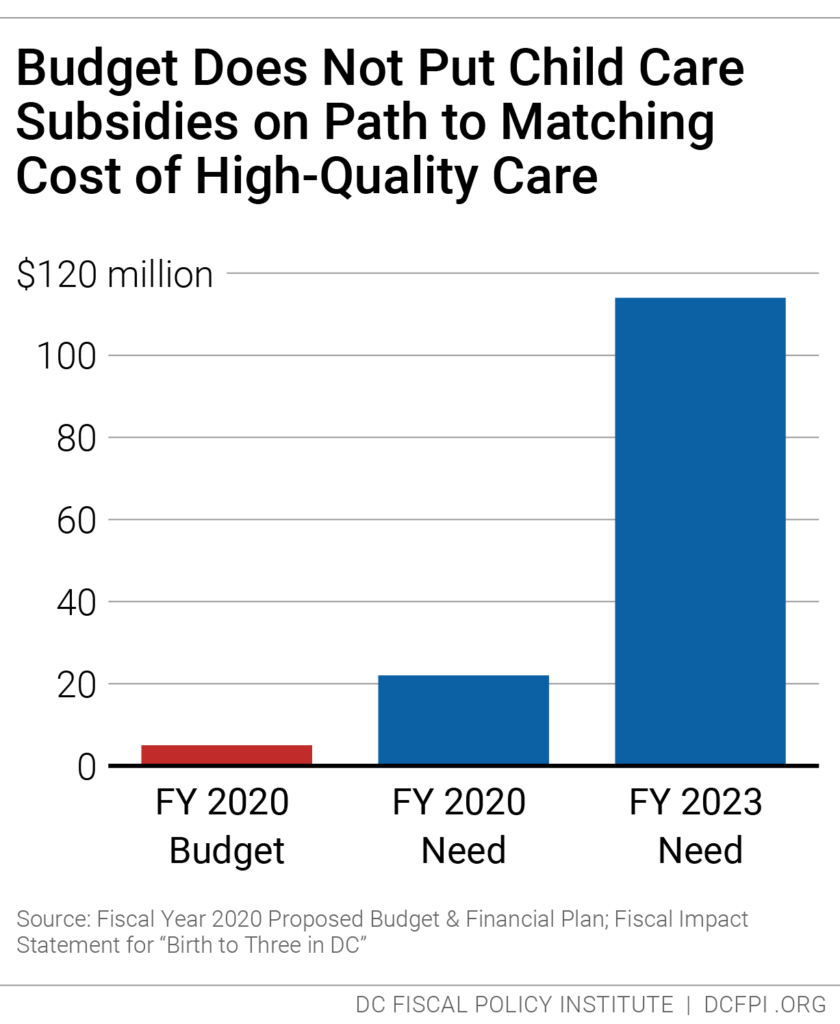

The proposed FY 2020 budget shows examples of both inequitable and equitable tax policies. The budget makes permanent a $1,000 tax credit for child care expenses that was included in the FY 2019 budget on a one-time basis. The subsidy’s maximum income eligibility of $750,000 means that the tax break is not well targeted to those with the greatest challenges affording child care. At the same time, the proposed budget provides just $5 million to improve the quality of child care for children in low-income families under the “Birth-to-Three for All DC” Act, far less than the $22 million needed (Figure 6). We must call into question tax cuts prioritizing white and affluent residents, while leaving residents of color on the backburner. The Council should eliminate the tax credit and invest those resources in the child care subsidy program. Child care affordability for moderate-income families should be addressed after investments to support the subsidy program have been made.

The tax proposals that promote equity include an increase in DC’s property tax credit for low- and moderate-income residents with high property tax burdens. The proposal for the “Keep DC Affordable” tax credit (formerly known as Schedule H) would increase the maximum income eligibility to $65,000 for non-seniors and $80,000 for seniors, up from $52,000 and $70,000, respectively. It also would increase the maximum credit amount to $1,200 from $1,025. This will help lower-income District residents, who disproportionately are residents of color, to keep up with the growing costs of rent or property taxes.

Additionally, Mayor Bowser’s budget proposal to raise revenues to support the overall budget through increased taxes on commercial properties would make the tax system more equitable. This would raise revenue from owners of DC’s most substantial commercial properties and fund services in the DC budget, which can promote equity and support residents who historically have been left on the backburner.

[1] Given DC’s history as a majority-Black city, this report primarily focuses on the systemic barriers imposed on Black residents and how the budget can advance opportunity for these residents.

[2] DC Council, B23-0833 Racial Equity Achieves Results Amendment Act of 2019

[3] These are scores in English Language Arts, from “DC’s 2018 PARCC Results,” Office of the State Superintendent of Education.

[4] DC Office of Planning, District of Columbia Census 2010 Demographic and Housing Profiles by Ward

[5] DC Economic Strategy, Household Income by Race and Ward, 2019.

[6] Jordan Fischer, “300 applications per seat? See which DC schools were the most sought-after in the 2019-2020 lottery,” WUSA9, April 4, 2019.

[7] Martin Austermuhle, “What You Need To Know About The D.C. School Lottery,” WAMU 88.5, March 28, 2019.

[8] According to an analysis by DCPS budget expert Mary Levy.

[9] DCPS defines students at-risk of academic failure as those who are in foster care, experiencing homelessness, are over age for their grade, or participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

[10] As recommended by a 2013 DC Education Adequacy Study commissioned by the DC government.

[11] Ed Lazere, No Way to Run a Healthcare Program: DC’s Access Barriers for Immigrants Contribute to Poor Outcomes and Higher Costs, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, March 17, 2019.

[12] Data USA, Washington, DC

[13] Prologue DC, Mapping Segregation in Washington, DC

[14] Christina Sturdivant Sani, Homes in Black Neighborhoods are Vastly Undervalued, Costing Black Homeowners Billions, Greater Greater Washington, December 20, 2018.

[15] Kilolo Kijakazi, Rachel Marie Brooks Atkins, Mark Paul, Anne E. Price, Darrick Hamilton, Willian A. Darity Jr, The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital, Urban Institute, November 2016.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Claire Zippel, Building the Foundation: A Blueprint for Creating Affordable Housing for DC’s Lowest-Income Residents, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, April 4, 2018.

[18] Cheryl Cort and Patrick McAnaney, Making Workforce Housing Work, Coalition for Smarter Growth, March 2019.

[19] Claire Zippel, DC’s Public Housing: An Important Resource at Risk, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, January 27, 2016.

[20] Popkin, et al. “A Decade of HOPE VI: Research Findings and Policy Challenges.” The Urban Institute and The Brookings Institution. May 2004.

[21] James Tracy. “HOPE VI Mixed-Income Housing Projects Displace Poor People.” Race, Poverty and the Environment.

[22] Mark Anderson. “How DC’s Plan to Save Low-Income Housing Went Wrong.” Washington City Paper, October 2014.

[23] ACLU DC, NEAR Act Stop & Frisk Data Collection, March 28, 2018.

[24] Stop Police Terror Project DC, Campaign to End Stop-and-Frisk in Washington DC

[25] ACLU DC, NEAR Act Stop & Frisk Data Collection, March 28, 2018.

[26] ACLU DC, The NEAR Act: An Evidence-Based Program to Promote Public Safety in the District, May 25, 2017; Brent J. Cohen, Implementing the NEAR Act to Reduce Violence in D.C., D.C. Policy Center, May 27, 2017.

[27] This is similar to, but separate from, the Cure the Streets program that is run by the Office of the Attorney General

[28] Peter Herman, “He used to sell drugs on D.C. streets. Now he’s paid to make them safer.” The Washington Post, December 14, 2018.

[29] Natacia Knapper, Statement on Behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union of the District of Columbia Before the DC council Committee on Judiciary and Public Safety, Budget Oversight Hearing on the Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement. April 11, 2019.

[30] Mike DeBonis, “How many more police officers does D.C. need? Depends on whom you ask.” The Washington Post, May 5, 2011.

[31] Government of the District of Columbia, Investing in Safety: New Investments for FY 2020

[32] Bill Meyers, “D.C. Is Teeming With Police Officers, So The Mystery May Be Why Crime Happens At All.” Washington City Paper, September 21, 2017; Governing, “Police Employment, Officers Per Capita Rates for U.S. Cities,” updated July 2, 2018.

[33] This $375,000 increase builds on last year’s $2.2 million investment for violence interruption through the Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement (ONSE)

[34] Martin Austermuhle, “Tax Revenue From D.C. Sports Betting Meant For Education, Violence Prevention May Go Elsewhere,” WAMU 88.5, March 25, 2019.

[35] Matt Cohen, “Judge to Order City to Start Collecting NEAR Act Stop-and-Frisk Data,” Washington City Paper, November 17, 2018; ACLU DC, NEAR Act Stop & Frisk Data Collection, March 28, 2018.

[36] Kery Murakami, “New figures shows decline in number of low-income workers who ride Metro” The Washington Post, December 18, 2018.

[37] Kery Murakami, “Data shows areas near Metro stations remain havens for the rich” The Washington Post, March 11, 2019.

[38] George Joseph, “Mapping Who Will be Hurt by D.C. Metro’s Late-Night Cuts” City Lab, December 22, 2016.

[39] DCFPI analysis of 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-year estimates.

[40] The DC Department of Transportation Director reported that the Ward 7 route will serve Eastern Market, Penn Branch, and Skyland Shopping Center. Committee on Transportation and the Environment Budget Oversight Hearing for the Department of Transportation. April 11, 2019. This analysis assumes that the route will connect Eastern Market to Penn Branch via Pennsylvania Avenue with stops along Pennsylvania Avenue.

[41] Transit Center, Should Transit Be Free? January 28, 2019.

[42] Misha Hill, Alan Essig, Meg Wiehe, Jenice Robinson, Steve Wamhoff, and Carl Davis, The Illusion of Race-Neutral Tax Policy, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, February 2019.

[43] Michael Leachman, Michael Mitchell, Nicholas Johnson, Erica Williams, Advancing Racial Equity with State Policy, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 15, 2018.

[44] Claire Zippel, Federal and DC Tax Changes Are A Windfall for DC Residents With Incomes Above $500,000, But A Mixed Bag for Those Below $50,000, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, May 7, 2018.

[45] Meg Wiehe, Emanuel Nieves, Jeremie Greer, and David Newville, Race, Wealth and Taxes: How the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Supercharges the Racial Wealth Divide, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and Prosperity Now, 2018.

[46] Meg Wiehe, Aidan Davis, Carl Davis, Matt Gardner, Lisa Christensen Gee, Dylan Grundman, Who Pays? Sixth Edition, October 2018.