Educators are the foundation of DC’s early learning system, shaping the most formative years of infants’ and toddlers’ mental, emotional, and social development. Paying early childhood educators livable salaries is one step needed to boost teacher satisfaction, retention, and quality care, thereby improving DC’s early learning system.[1] Nearly 4,000 early childhood educators, most of whom are long underpaid Black and brown women, have received supplemental wage increases since the launch of the District’s Pay Equity Fund (PEF) in 2022, and over 1,000 educators and their families have been covered by the PEF health care program, HealthCare4ChildCare (HC4CC).

As DC local fund revenue growth slows, lawmakers must protect the PEF from another funding raid and anticipate the natural growth in cost that accompanies its successful implementation and outcomes in future years. While fiscal year (FY) 2024 funding is enough for what is required in the law and for those who are currently eligible—thanks to prior year carryover dollars—additional funding will be needed in future years as teacher salaries rise, more early educators qualify for higher salary levels due to higher credentials, and administrative costs increase. Program improvements that would enhance equity also would increase costs, if adopted.

The DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI) estimates that natural growth in costs to the program will be:

- $6.9 million alone for a projected 3 percent adjustment to minimum salaries in the PEF to account for anticipated Washington Teacher Union (WTU) contract negotiations.

- Or, up to $21.8 million for the projected salary adjustment plus the cost for higher award payments to providers as more early childhood educators attain new credentials to comply with DC law and qualify for higher minimum salaries, assuming DC sees a sizeable increase in credential attainment.[2]

- And, $561,000 for additional administrative costs that the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) may need to run the program under these combined cost pressures.

- Some of the higher cost could be offset with recurring revenue that is already in the financial plan for FY 2025 (when backing out the one-time $12.3 million supplement in FY 2024), and any of the remaining $7.3 million in carryover dollars from FY 2023 that may be available at the end of FY 2024.

Lawmakers should also prepare for increases in future years to account for growing costs, such as improving the funding formula and as even more educators gain the credentials required under law. Additionally, if lawmakers pursue a fully equitable system and choose to adopt the full salary scale that rewards educators’ experience as intended by the PEF and Birth-to-Three for All DC Act, the additional cost would grow to $33.6 million in FY 2025, when also accounting for the anticipated 3 percent adjustment and credential increase. It is critical to protect the current budget for the PEF while keeping up with natural cost growth to ensure that all participating educators receive the salaries they deserve and to achieve pay parity with DC Public School (DCPS) teachers.

The Pay Equity Fund Repairs Racist Harm Embedded in the Early Education System

In 2018, the District passed the Birth-to-Three for All DC Act (Birth-to-Three Act), which is designed to ensure that every child, beginning from birth, receives an equitable and high-quality education, particularly in the years before they turn three, when they can enter DC’s universal pre-k program. A core component of the law is pay parity for early educators, defined as compensation equivalent to the average base salary and fringe benefits of an elementary school teacher employed by DCPS with the equivalent role, credentials, and experience.[3]

To achieve the vision set by the Birth-to-Three Act, DC Council approved a modest income tax increase on the District’s highest income residents in 2021, in part to finance substantial pay increases for approximately 4,000 early educators primarily caring for infants and toddlers through the creation of the PEF.[4] The compensation program disrupts the pervasive and centuries-long undervaluing of caregiving that has, due to structural racism and sexism, disproportionately harmed Black and brown women.

Although the work of teaching and caring for young children is highly skilled and complex, early education is one of the most underpaid sectors in the District. The historical undervaluing of the early education workforce has deep roots in white supremacist ideology and sexism.[5] Low pay is also a result of decades of government underinvestment and a market-based system that operates on tight margins, due to a large dependence on parent fees and high fixed costs associated with low child-to-teacher ratios.[6] Educators in DC with a bachelor’s degree take a 33 percent pay penalty if they choose to work with young children, rather than older children in elementary schools.[7] And this disparity is especially harmful to Black and brown educators, as they are more likely to work with infants and toddlers than white educators nationally.[8]

The Current Design of the PEF Needs Improvement

The PEF seeks to close the compensation gap between early childhood educators and elementary school educators through payments to child development facilities (CDFs) to increase salaries and the new HC4CC program that offers no- and low-cost health care coverage to CDFs. Policymakers established an Early Childhood Educator Task Force (the Task Force) comprised of early childhood education stakeholders, including providers, educators, advocates, and policy experts, to submit recommendations on the design of the compensation program to the mayor and the DC Council. In FY 2023, OSSE disbursed over $41.5 million in supplemental payments directly to early childhood educators through the PEF.[9] Beginning December 2023, the PEF provided payments to CDFs who in turn are paying teachers directly.

While most of the parameters of OSSE’s formula for PEF payments to CDFs are aligned with recommendations from the Task Force, the formula is pegged to entry-level salaries rather than the full salary scale. The result is that it fails to reward experience and thereby undermines one of the Task Force’s main recommendations.[10] To retain staff and reward them for the value they bring to the early education system, the formula’s design needs improvement.

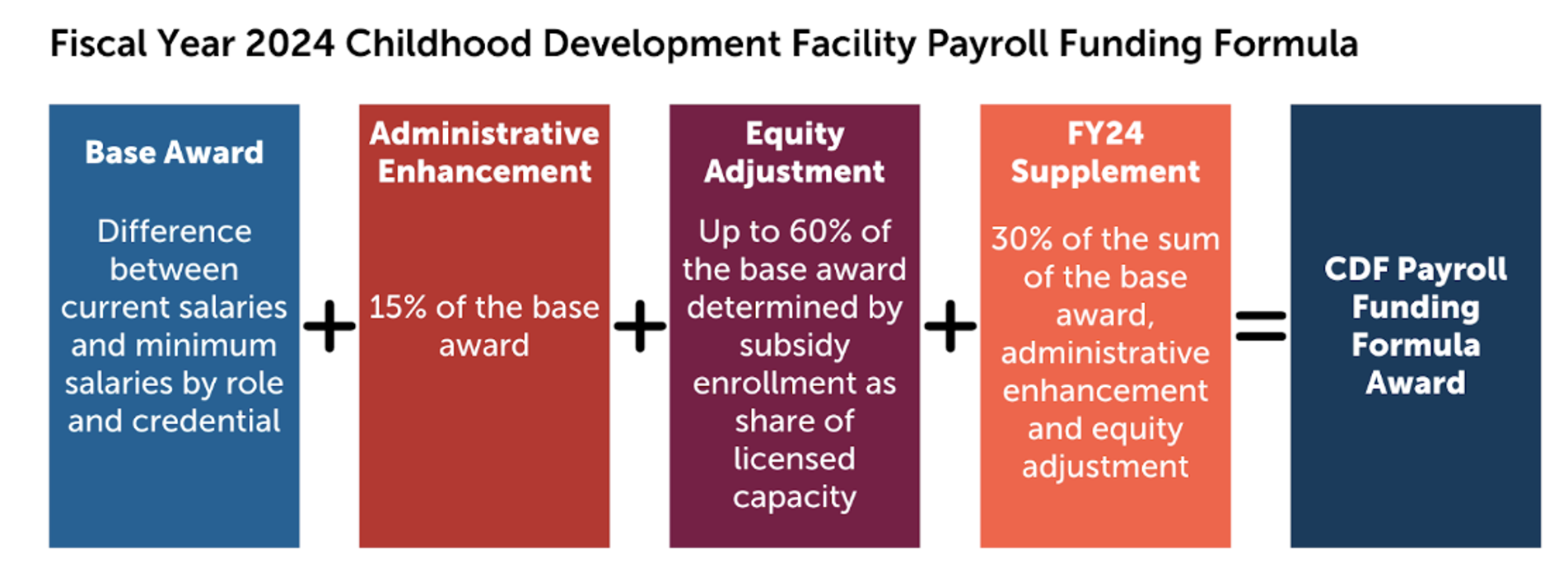

CDFs and homes that are OSSE-licensed must opt into the program to receive a payroll award, which is comprised of three parts:

- A base award—the difference between current salaries and OSSE-required minimum salaries by role and credential per full-time educator;[11]

- An administrative enhancement (15 percent of the base award to help cover the cost of implementation); and,

- An equity adjustment—up to 60 percent of the base award determined by child care subsidy enrollment as share of the center or home’s licensed capacity.

The equity adjustment is an important component of the formula because it is an added benefit to facilities that serve families with low incomes who use public vouchers to pay all or most of their child care fees. For FY 2024, OSSE estimates the total cost of the PEF at $74.7 million, assuming 100 percent of CDF participation in the payroll component. This is above the approved budget of $69.5 million, but OSSE is using carryover funding to bridge the gap.[12]

This amount also includes a one-time 30 percent supplement to awards to help facilities meet the minimum salary requirements of the program in FY 2024 (Figure 1).

OSSE is offering the temporary 30 percent increase because without it, some CDFs would receive awards that fall short of what’s needed to meet the minimum salary requirements, which would leave them unable to afford participation in the program. This is a result of a flaw in the design that sets the base award as the difference between average current salaries, by role and credential, and the minimum OSSE-required salaries. For providers with a higher share of teachers with below average current salaries, their base award could be too small for them to fully meet the program requirements without the supplemental support. A better method would set the base award as the difference between the median of current salaries or the minimum wage and the minimum OSSE-required salaries to align the award amounts more closely to the reality of how much educators are currently being paid.[13] OSSE also created a waiver for the CDFs that will be unable to meet requirements even with the supplemental support.[14]

The minimum required salaries also reflect the very bottom of the DCPS salary scale for elementary school teachers, which limits the ability of participating CDFs to pay eligible educators based on experience, as intended by the Birth-to-Three Act and recommended by the Task Force. Failing to permanently fix the design of the award formula (and eventually adopt the full salary scale versus just minimum salaries) could result in unnecessarily limiting pay for educators and disincentivizing longevity in the field. If DC retains fewer experienced educators, it could reduce the quality learning for young children.[15]

Success of the Early Educator Compensation Program Grows its Cost in Future Years

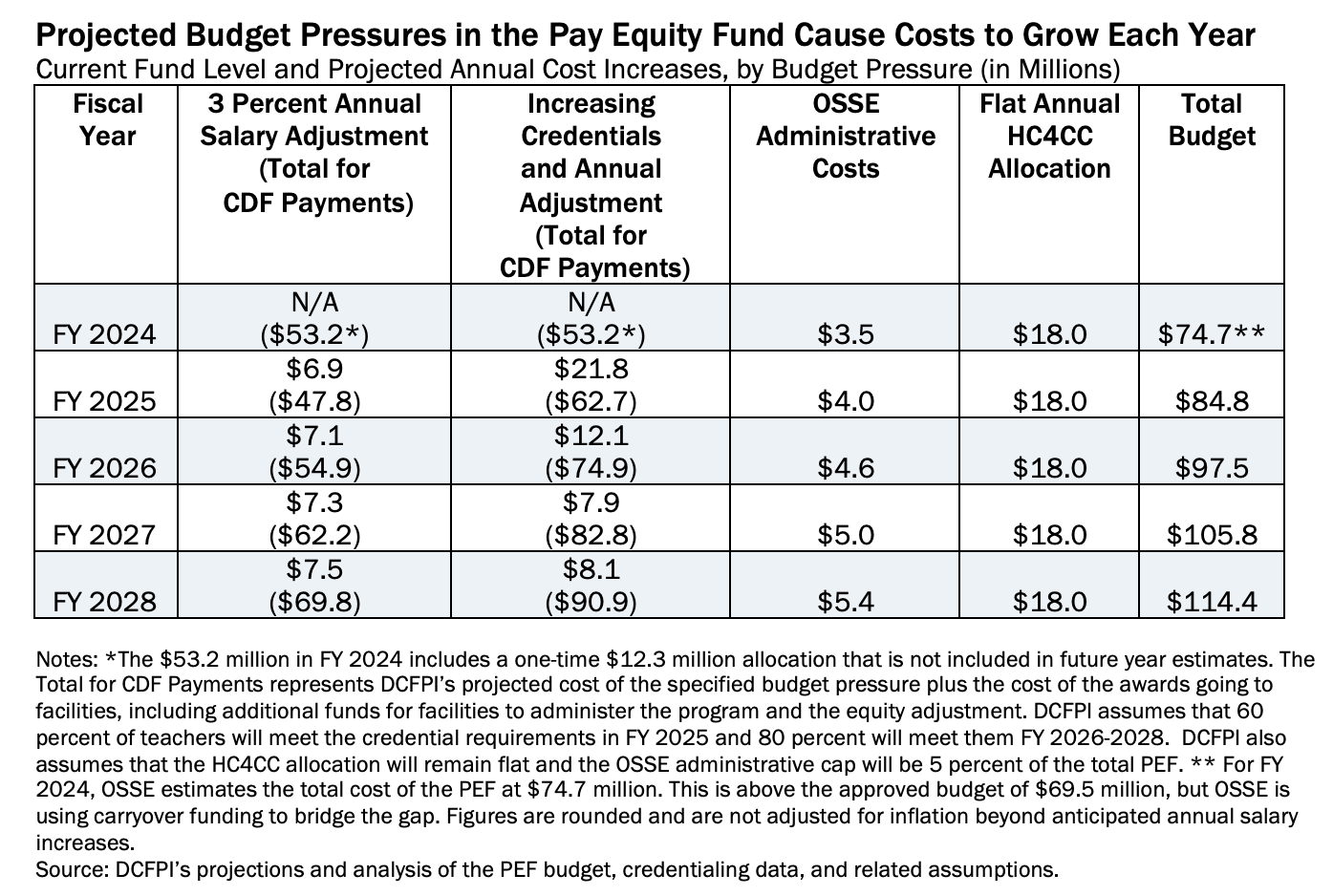

In the first quarter of FY 2024, 85 percent of providers opted to participate in the PEF—and, importantly, over two-thirds of those providers offer subsidy-eligible slots to children in families with low and moderate incomes. While total funds in the PEF (recurring and carryover dollars) are currently adequate to cover program costs in FY 2024, additional funding will be necessary as carryover dollars are used up. In addition, lawmakers should anticipate annual increases to the cost of the program due to its most promising features. For example, costs will rise as early educators’ salaries line up with DCPS teacher salary increases, more educators attain higher credentialing and become eligible for higher minimum salaries, and administrative costs that are set as a share of total cost go up. Table 1 details the current FY 2024 PEF program costs and the amount of funding DC lawmakers need to invest in the PEF for FY 2025 through FY 2028, if it were to keep up with projected rising costs of the program.

To project future costs resulting from intended program growth, DCFPI took a phased-in approach:[16]

- The total cost for FY 2025 is based on the current CDF payroll funding formula but without the temporary 30 percent increase to base awards that is only available in FY 2024, plus a projected 3 percent adjustment to minimum salaries to account for anticipated WTU contract negotiations. This cost also assumes that 60 percent of educators will meet the credentialing requirements in FY 2025, up from 40 percent in FY 2024, as discussed later in this report.

- The total costs for FY 2026 through FY 2028 are calculated the same as FY 2025 except they assume 80 percent of educators meet the credential requirements.

- The total for each year also assumes continuation of the $18 million allocation for HC4CC and administrative costs that are capped at the maximum-allowed level of 5 percent of the total PEF appropriation.

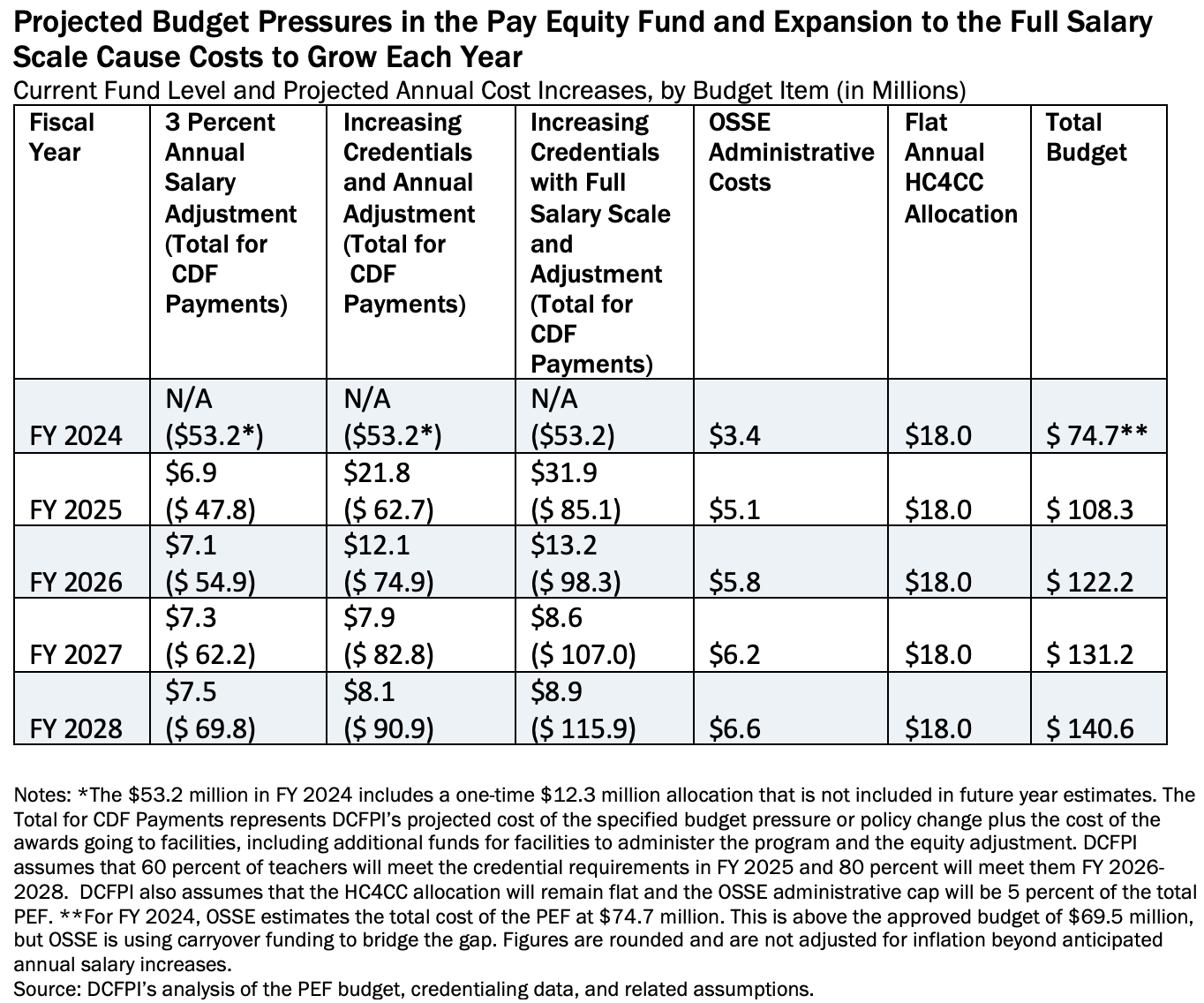

These are the natural cost pressures associated with maintenance of the program. To implement the PEF in a manner fully in line with the Task Force recommendations—namely adoption of a full salary scale based on credentials and years of experience–future costs would be higher. Table 2 presents the current FY 2024 PEF program budget, and the amount of funding DC lawmakers need to invest in FY 2025 through FY 2028 if it were to keep up with projected rising costs of the program, and adoption of a full salary scale in FY 2025.[17]

Potential Additional Costs Not Included in Projections

There are other factors that may cause the annual program cost to increase as well. Demand for child care is likely to increase as child care subsidy eligibility expands and as more workers return to working in offices instead of at home. However, DC is seeing a decline in birth rates that may offset any increase in demand.[18] If demand for child care increases, supply will likely increase as well, requiring more early educators to enter the field. As the number of early educators increases, the total cost of the PEF will increase.

There may also be future changes to the program that would drive higher costs. The equity adjustment, intended to award CDFs that serve families who are eligible for child care subsidy, is currently just over 3 percent of the overall annual cost of the PEF, even with the increase of the award amount going to those facilities. Policymakers need to adopt further improvements to increase the benefit of the equity adjustment to encourage more providers to serve families with low incomes who currently have limited child care options. Future iterations of the PEF may—and should—include funding for salary increases for CDF directors. As educator pay increases annually, some educators will start to make more than their directors, which could negatively impact interest in and retention of leadership—a critical quality both in terms of pedagogy and facility operations in early childhood education.

Participation in the PEF requires significant data sharing between OSSE and CDFs on educator salaries and credential levels. As OSSE collects more data during FY 2024 implementation, OSSE can be more precise in how it distributes PEF funds to ensure all CDFs can meet the mandated salary requirements.

Early Educators Should Receive Annual Salary Adjustments in Line with DCPS Teachers

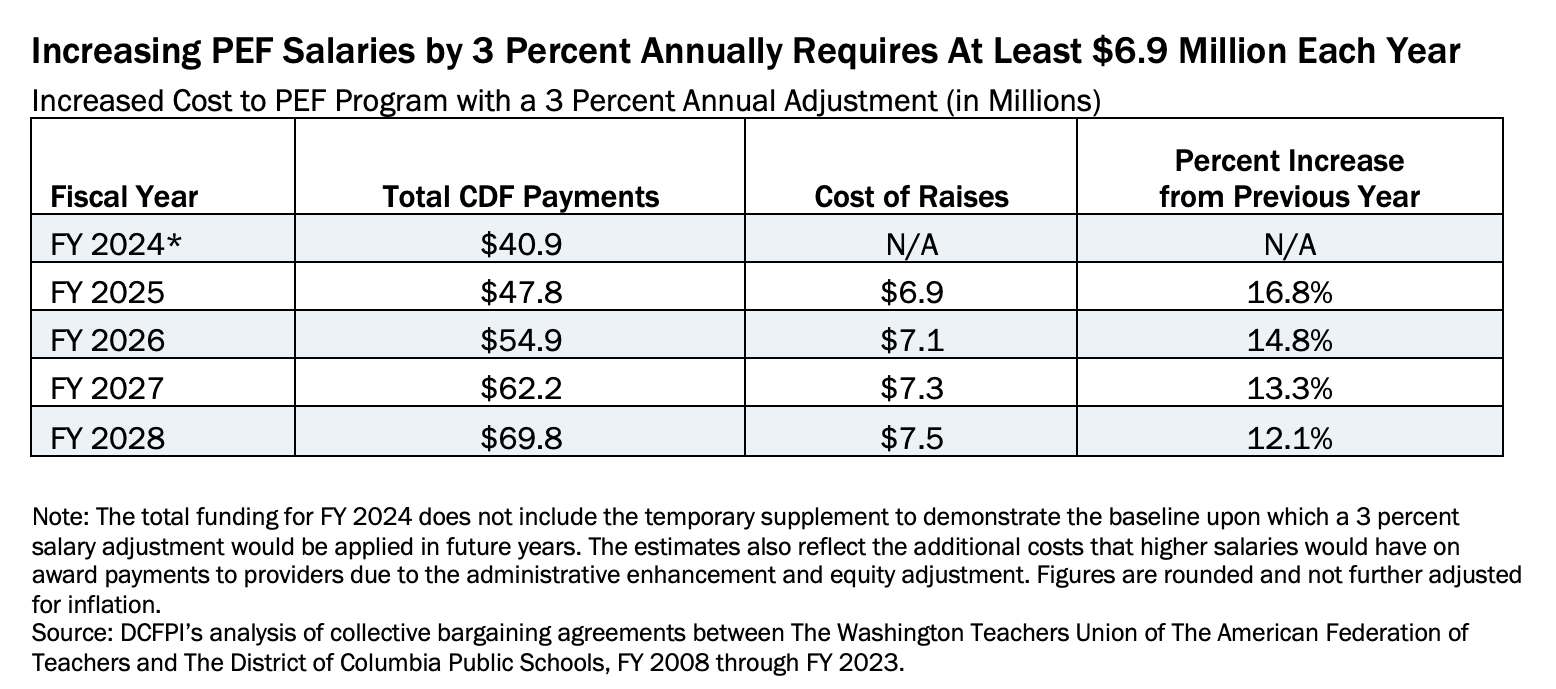

One of the largest natural cost pressures in the PEF, and a key step in achieving pay parity is the annual salary adjustment needed to keep early educator pay in line with the annual salary increases that DCPS teachers receive as a result of WTU negotiations.

Every several years, WTU negotiates annual salary adjustments for public school teachers to ensure that salaries keep up with increasing inflation and cost of living. In the previous three contracts negotiated by the WTU, the average annual adjustment for each contract period was 4 percent from FY 2008 to FY 2012, 3 percent from FY 2017 to FY 2019, and 3 percent from FY 2020 to FY 2023. There was no contract from FY 2013 to FY 2016, and WTU is still negotiating the contract for FY 2024.[19] DCFPI analysis assumes the PEF will require a 3 percent annual adjustment to early educator salaries, which is just above the overall average adjustment rate (2.74 percent) across FY 2008 to FY 2023. By statute, annual salary increases cannot exceed 3 percent.[20]

For the current workforce, a 3 percent annual salary increase for early educators would require an additional $6.9 million to $7.5 million increase in funding annually through FY 2028 (Table 3). To isolate the cost of a salary increase, DCFPI bases its estimates on the most current credential levels held by early educators, rather than projected increased levels. The total cost for FY 2024 includes the temporary 30 percent award supplement. Because this supplement is not expected in future years, it is excluded from the FY 2024 baseline, upon which a 3 percent salary adjustment would apply. (However, the District should permanently increase award amounts in a way that ensures all CDFs can participate in the program.)

As Early Educators Earn Higher Credentials, Compensation Program Costs Increase

Another factor that by design increases the cost of the PEF over time is a 2016 child care licensing regulation, which increases the minimum education requirements for early childhood educators and directors of CDFs. As of December 2023, the District requires that lead teachers, home caregivers, and expanded home caregivers have an associate degree or higher, and that assistant teachers and associate home caregivers have a Child Development associate degree or higher.[21] As more early educators earn higher credentials, the minimum salaries for which they’re eligible under the PEF increase, as does the cost of the program. Facilities that employ educators who do not meet the required credentials are subject to licensing deficiencies and may be subject to enforcement actions. However, OSSE currently allows educators working on an associate or bachelor’s degree to stay in their positions for up to four years while they complete their programs; educators working on a CDA have a two-year extension to earn their degree.[22]

Most recent data shows that about 40 percent of early educators, overall, are currently meeting the credential requirements for their role, with home-based educators experiencing higher rates of degree attainment than their center-based peers.[23] Because the licensing regulation went into effect in December 2023, and because the PEF is unprecedented in the nation, there is limited reliable data available to predict how quickly early educators will attain the required credentials. On the one hand, the licensing deficiencies system is an incentive for providers to hire and retain qualified staff, and the significant salary increase that the PEF offers is another powerful incentive for early educators to attain their credentials.[24] On the other, barriers to higher education and other factors—such as family obligations outside of work—may slow educators’ ability to gain the required credentials.

The experience of CDF directors offers limited evidence. In December 2022, OSSE began requiring directors to have a minimum of a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education. Prior to the requirement going into effect, about 82 percent of center directors met this requirement. Throughout 2023, the percentage has stayed around 86 to 87 percent, according to OSSE.[25] It is reasonable to believe that teachers and teacher assistants will attain the required credentials at faster rates because those credentials likely take less time to obtain and because there is the benefit of significantly higher salaries.

Given these factors, DCFPI assumes educators will meet the requirements about twice as fast as directors, rising to 60 percent over the next two fiscal years (or by the end of FY 2025), especially as competition for these roles increase due to increasing salaries and benefits. For FY 2026 and future years, DCFPI assumes that 80 percent of educators will meet the requirements and that percentage will hold steady year to year. DCFPI assumes that, at most, only 80 percent of early educators at any given time will meet the new credential requirements in the upcoming financial plan because of potential delays in attainment and new educators entering the field.[26]

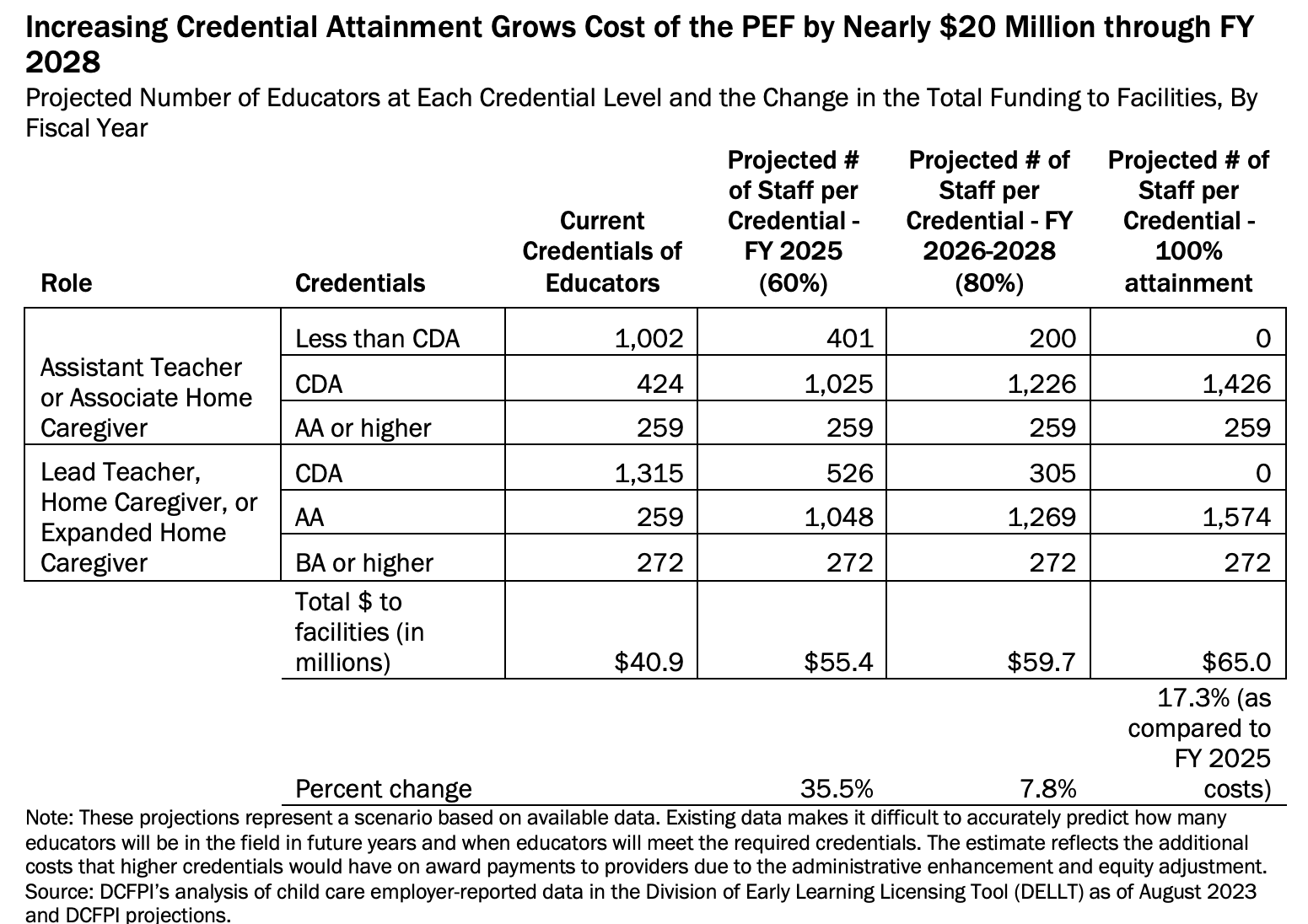

The projected increases in credentialing would raise the cost of the PEF program by $14.5 million, or 35.5 percent in FY 2025 (Table 4). In FY 2026, the cost of the PEF program increases by $4.3 million (7.8 percent), from the previous year, with the estimate staying flat through FY 2028 as attainment levels remain at 80 percent.[27]

Educators who did not fully meet the licensing requirements by December 2023 may qualify for a waiver if they can 1) demonstrate immediate economic impact or hardship that made immediate compliance with the requirement impractical, 2) if the educator is meeting or exceeding the intent of the credential requirement, and 3) if the health and welfare of staff and children are not jeopardized.[28] Additionally, center directors, expanded home caregivers, and teachers who have continuously served in the same or comparable role since December 2006 or earlier, without a significant gap in service, may qualify for a ten-year continuous service waiver. To receive the 10 years of continuous service waiver, a center director, expanded home caregiver, or teacher must show that they had ten years of continuous service as of December 2016 when the licensing regulations were published.[29]

Rising Program Costs Could Also Increase Administrative Costs

The PEF law allows OSSE to dedicate up to 5 percent of the annual fund towards program administrative costs. As awards for facilities increase, the cost to administer the program may also increase. These administrative costs may include additional personnel costs, expenses related to distributing awards to CDFs, costs related to providing technical assistance to CDFs, and costs of conducting outreach to early educators and facilities to support the implementation of the PEF.[30]

The District Should Maintain Current Budget for Educator Health Coverage Given Projected Increase in Utilization and Cost

Health insurance is a critical component of PEF compensation. The PEF law allows OSSE to use “excess funding” available after CDF payments to pay for a health care program called HealthCare4ChildCare (HC4CC), which makes free or low-cost health care coverage available to child care workers who live in the District and non-District child care workers whose employers purchase coverage through the DC Health Benefit Exchange (DCHBX).

In FY 2023, OSSE allocated $18 million in PEF funds for HC4CC. The DCHBX operates HC4CC with the goal of getting every early educator the best health coverage option for their needs, whether it is through Medicaid or DCHBX. As of October 1, 2023, HC4CC provides health care coverage to 1,021 individuals (employees and dependents) across 168 facilities, and 50 employers are able to offer health insurance to their staff for the first time ever.[31] To increase the number of people covered as the program gets up off the ground, DCHBX awards non-PEF funded grants to trusted community organizations to educate CDFs about HC4CC and encourage employers and employees to enroll.

To further incentivize enrollment for plan year 2024, the HC4CC premium discount is based on the lowest cost Gold Standard plan, which has lower cost sharing than the Silver plan that DCHBX offered in 2023. Additionally, for the 2024 plan year, employers will have the option to cover both DC residents and non-residents in their group plan, which was only possible in 2023 for employers that already offered group coverage to their employees and was a barrier to entry for some CDFs.[32] (Coverage extends to resident workers’ spouses and dependents but does not for non-resident workers’ spouses and dependents.)

As DCHBX implements these improvements and outreach continues, more facilities are likely to utilize HC4CC, especially as the child care industry recovers and enrollment and staffing levels increase, therefore increasing HC4CC expenditures. The cost of health care increases annually, which will also drive up HC4CC expenditures over time. The current $18 million allocation for HC4CC is adequate to absorb these growing costs, and it’s important to maintain this level in the PEF budget to ensure that this benefit remains available to all early educators. After the implementation of the PEF in quarter one of FY 2024 and Medicaid redeterminations in spring 2024, DC will have more accurate data on utilization rates and a better understanding of why early educators may not be accessing this resource, as well as the cost to implement HC4CC over time.

Spending pressures in the salary program could put HC4CC at risk, given the PEF statute gives priority to funding salaries through the “excess funding” provision in the law.[33] If cost pressures balloon without an increase in revenues, there’s a risk that thousands of educators could lose access to HC4CC subsidies. It is crucial for DC lawmakers to plan for PEF cost pressures to protect what OSSE and DCHBX is building.

True Pay Parity Would Reward Experience and Be Worth the Cost

DCPS pays teachers on a salary scale that accounts for credentialing and years of experience.[34] While the PEF uses the same salary scale, the law only requires CDFs to pay minimum (i.e., entry-level) salaries on that scale regardless of educators’ experience, keeping the program from reaching true pay parity with DCPS. As educators increase their years of experience in the field, they should see an increase to their salary, not just when they increase their credential levels, as the program is currently designed. Implementing a full salary scale based on credentials and years of experience will increase the total cost of the PEF.[35]

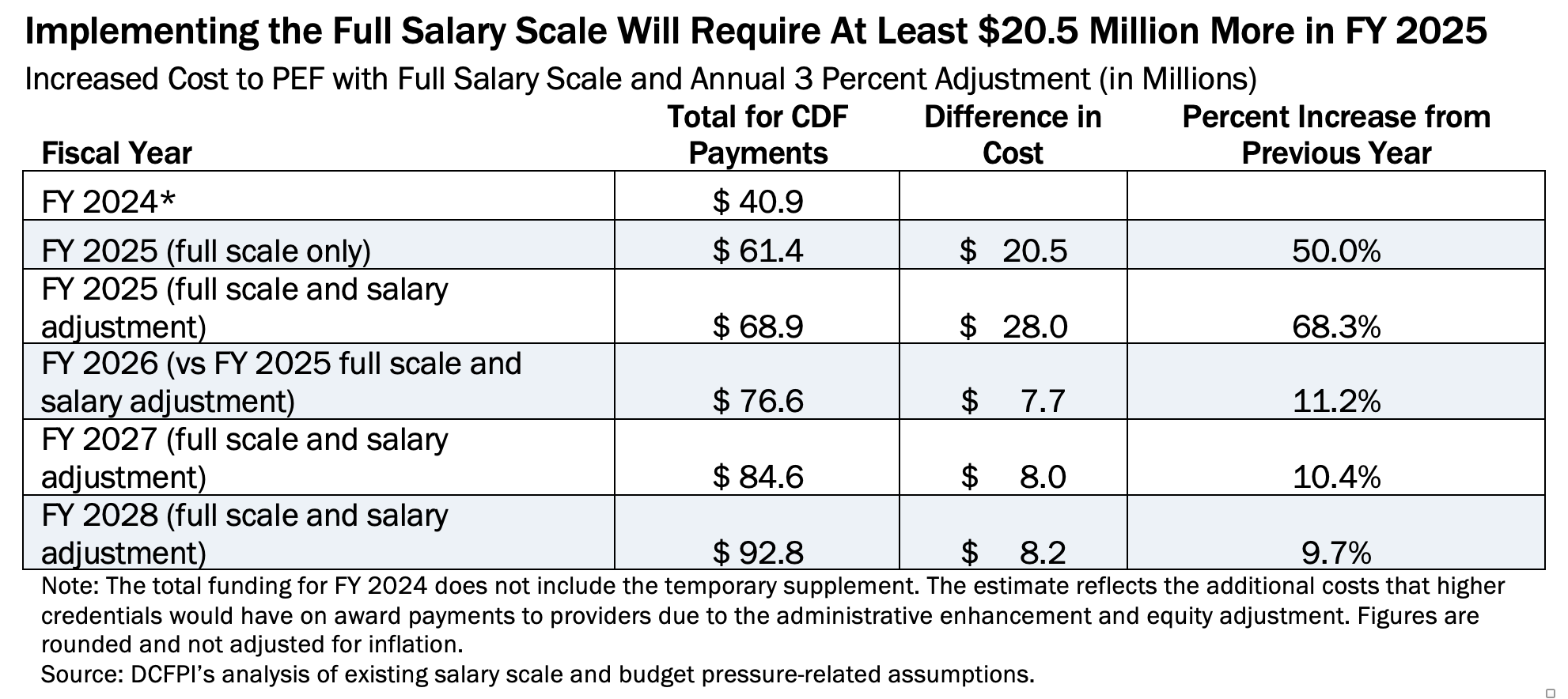

To determine the total annual cost of the PEF if the full salary scale were implemented, DCFPI used the middle of the salary scale as a proxy for the average salary and based the award on the difference between current average salaries and the average (midpoint) of the salary scale per position and credential. To capture the cost of paying educators based on experience, our analysis uses the midpoint (Step 5) to align with the Task Force’s methodology. Currently, the PEF only requires CDFs to increase educator salaries to Step 1 of the salary scale, representing the absolute minimum level of experience.[36] Table 5 shows how the total funding going to CDFs increases if OSSE were to implement a full salary scale in FY 2025 and a full salary scale and 3 percent annual adjustment in FY 2025 through FY 2028.

To fully achieve pay parity with DCPS teachers, the PEF formula should use both the full salary scale and update award levels each time the WTU negotiates a new scale and DCPS implements those changes. If OSSE implements the full salary scale in FY 2025 without the 3 percent annual adjustment, it would cost an additional $20.5 million, or a 50 percent increase, than the total amount paid to facilities in FY 2024 budget (without the one-time supplement and assuming the number of educators per credential level remains the same). If OSSE implements both the full salary scale and the 3 percent adjustment in FY 2025, it would cost about $28 million more than the total to facilities in FY 2024. The total cost for the following years in Table 5 reflects annual increases ranging between $7.7 million to $8.2 million, or the amount to keep up with annual salary increases once a full scale is adopted in FY 2025.

The purpose of the PEF is to bolster wages for early childhood educators to achieve pay parity with DCPS educators. To accomplish this, lawmakers should increase funding levels for the PEF to include an annual 3 percent salary adjustment, keep up with increasing credential attainments, and implement a salary scale based on credential level and years of experience. These changes are costly, but necessary to achieve the promise that lawmakers made in the Birth-to-Three Act.

[1] Rob Grunewald, Ryan Nunn, and Vanessa Palmer, Examining Teacher Turnover in Early Care and Education, April 2022.

[2] The estimates in the first two bullets reflect the additional costs that higher salaries and credentials will have on award payments to providers (due to the administrative enhancement and equity adjustment).

[3] DC Law 22-179: Birth-to-Three for All DC Amendment Act of 2018.

[4] Tazra Mitchell, New Local and Federal Revenue Help Advance Tax and Racial Justice and Helps Residents Thrive, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, November 2021.

[5] For more discussion, see: Danielle Hamer and Tazra Mitchell, DC Makes Bold Progress on Fair Pay for Early Educators, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, August 2022

[6] Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, Early Childhood Workforce Index 2020: Early Educator Pay & Economic Insecurity Across the States, 2020.

[7] Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, Early Childhood Workforce Index, State Profiles: District of Columbia, 2020.

[8] Lea J.E. Austin, Bethany Edwards, and Marcy Whitebook, Racial Wage Gaps in Early Education Employments, Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley, 2019.

[9] Division of Early Learning Newsletter, October 2023.

[10] Final Report of the Early Childhood Educator Equitable Compensation Task Force, Submitted to the Mayor and Council of the District of Columbia, March 23, 2022.

[11] DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Fiscal Year 2024 Minimum Salaries and Salary Schedule for Early Childhood Educators, 2023.

[12] DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Child Development Facility (CDF) Payroll Funding Formula September 2023 Update, 2023. See Table 2 on page 8.

[13] OSSE’s determination of average current salaries of early educators was informed by the 2022 DC Child Care Provider Survey and the 2023 Cost Modeling Analysis.

[14] DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Waiver Policy for Fiscal Year 2024 (FY24) Early Childhood Educator Pay Equity Fund, October 2023.

[15] Under 3 DC Coalition, FY25 Budget Letter to Mayor Bowser, October 6, 2023.

[16] It is possible that funds will be available to be carried over into FY 2025, as they were for FY 2024. Annual costs could be higher than DCFPI’s projections if OSSE extends the temporary award supplement beyond FY 2024. And costs would be lower if the CDF participation rate doesn’t reach 100 percent by the end of the fiscal year, the WTU contracts fall below the historical 3 percent average, and/or if teachers don’t achieve credential attainment at the levels DCFPI assumes in its projections. As the cost of each budget pressure builds on top of one another, the interactions of those pressures impact the estimates for the total CDF payments. It is not possible to add the isolated costs of individual changes to arrive at a total cost for the combined changes.

[17] Similar caveats to DCFPI’s projections apply to this estimate as those listed for Table 1. If 100 percent of educators meet the required credentials FY 2028 rather than 80 percent, it would cost the program an additional $6.8 million.

[18] Executive Office of the Mayor, Mayor Bowser Expands Access to Affordable High-Quality Child Care for DC Families, March 2023.

[19] DCFPI analysis of DCPS and WTU Collective Bargaining Agreements, SY 2008-2012, SY 2017-2019, and SY 2020-2023.

[20] Introduced by Chairman Mendelson at the request of the Mayor, “Fiscal Year 2020 Budget Support Act of 2019,” L23-0016, September 11, 2019.

[21] DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Early Childhood Educator Minimum Education Requirements January 2023, accessed September 2023.

[22] On December 20, 2023, State Superintendent Dr. Christina Grant signed a Notice of Emergency and Proposed Rulemaking (NEPRM) for the Licensing of Child Development Facilities, which proposes revisions to the current licensing regulations (5A DCMR Chapter 1). This change allows a teacher with a current Child Development Associate (CDA) credential, or comparable state-awarded certificate approved by OSSE, to be employed as a teacher provided that the teacher is enrolled in an associate or more advanced degree program and earns a degree within four years of their initial date of hire as a teacher in a child development center. OSSE may extend this deadline to six years if a teacher maintains continuous enrollment in a degree program or experiences a hardship interfering with studies (§ 165.1(e) and §165.2). The Notice also allows an assistant teacher to be employed as an assistant teacher provided that they earn a CDA credential, or its equivalent, within two years of their initial date of hire as an assistant teacher in a child development center (§ 166.1(d)). OSSE, Child Development Facilities Licensing Emergency and Proposed Rulemaking, Effective December 20, 2023.

[23] DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Early Childhood Educator Minimum Education Requirements, October 2023.

[24] For assistant teachers or associate home caregivers, the PEF awards individuals up to $7,000 more per year when they attain a CDA (the minimum requirement for these roles). For lead teachers, home caregivers, and expanded home caregivers, the PEF awards individuals up to $9,500 more per year when they attain an Associate Degree (the minimum requirement for these roles). OSSE, Child Development Facility (CDF) Payroll Funding Formula, September 2023 Update.

[25] DCFPI analysis of OSSE Quarterly Reports on the numbers and percentage of current early childhood educators in each role who have achieved the minimum education credential for their position as reported by employers in the Division of Early Learning Licensing Tool (DELLT), accessed January 2024.

[26] This assumption is also supported by OSSE data on the credential attainment of center directors. As of December 2022, center directors are required to have a minimum of a Bachelor’s degree in early childhood education. Prior to the requirement going into effect, about 82 percent of center directors met this requirement. OSSE has published quarterly reports on credential attainment throughout 2023 that show that credential attainment among center directors has stayed around 86 to 87 percent since the December 2022 deadline.

[27] While unlikely, if all educators meet the required credentials in FY 2026, the PEF program cost will increase by $9.6 million, or 17.3 percent, from the previous year. Under a scenario in which credentials are attained at a slower rate, the costs associated with increasing attainment would be lower than these projections.

[28] DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Education Requirements for the Early Childhood Workforce: Resources and Supports, accessed September 2023.

[29] DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Child Development Staff Education Requirements Frequently Asked Questions for Child Development Facility Leaders,March 2023.

[30] DC Law 24-492, Fiscal Year 2023 Budget Support Act, page 55.

[31] Mila Kofman, HealthCare4ChildCare Advisory Council Virtual Meeting slide deck, DC Health Benefit Exchange Authority, October 19, 2023.

[32] Mila Kofman, HealthCare4ChildCare Advisory Council Virtual Meeting slide deck, DC Health Benefit Exchange Authority, October 19, 2023.

[33] DC Law 24-492, Fiscal Year 2023 Budget Support Act, page 54.

[34] District of Columbia Public Schools, Washington Teachers’ Union Pay Scales, 2023.

[35] The Task Force developed and recommended a salary scale based on the DCPS teacher salary schedule effective October 9, 2022 (OSSE, Fiscal Year 2024 Minimum Salaries and Salary Schedule for Early Childhood Educators). The Pay Equity Fund Establishment Act required that this salary schedule be updated annually (Code of the District of Columbia, § 4–410.02. Payments to child development facilities. | D.C. Law Library (dccouncil.gov)).

[36] OSSE developed a 16-step salary scale based on the DCPS salary schedule that facilities can use to pay educators based on both education level and years of experience. Step 1 represents the absolute minimum level of education and experience and Step 16 represents the highest level of education and experience. The Taskforce uses Step 5 as an average salary point, so this analysis takes Step 5 as an average.