The DC budget is much more than numbers. It determines how the money we all pay together through taxes and fees are spent and reflects our priorities and values. While the DC budget exists to meet the needs of all residents and businesses, it is especially important to DC residents who are struggling to make ends meet. Because of a long history of racist policies and practices, DC’s Black and brown residents experience more job discrimination, inadequate access to health care, and a lack of affordable housing. Using the budget to prevent evictions, adequately fund all public schools, and get health care and cash to those who need it are just a few ways lawmakers can transform DC into a more equitable community where everyone can live well.

Through tax and spending choices, DC can invest in the public services that help our communities thrive, reduce longstanding racial and economic inequities, and build a strong foundation for the future. Together, we have the power to overcome the challenges the District faces and put our shared values into action.

This guide breaks down the process of how DC creates its budget, including how to read budget documents and where in the process residents can influence the decisions of elected officials. Words in bold are defined in the glossary at the end of the guide.

Table of Contents

- How the District Spends Its Money

- Where the District’s Money Comes From

- How the Budget is Created

- How to Read Budget Documents

- Other Budget Resources

- Glossary

How the District Spends Its Money

Every service DC provides, from trash collection to child care subsidies, appears in the budget every year and lawmakers add new services sometimes.

DC’s budget is divided into two parts:

- The operating budget allocates resources to run the city government day-to-day, paying for things such as the salaries of police officers and librarians, electricity and phone bills for government agencies, and health expenses for residents in the District’s health programs.

- The capital budget supports the costs associated with building and maintaining infrastructure such as roads and schools. Most of the time, when officials speak about the budget, they are talking about the operating budget. This guide also focuses primarily on the operating budget.

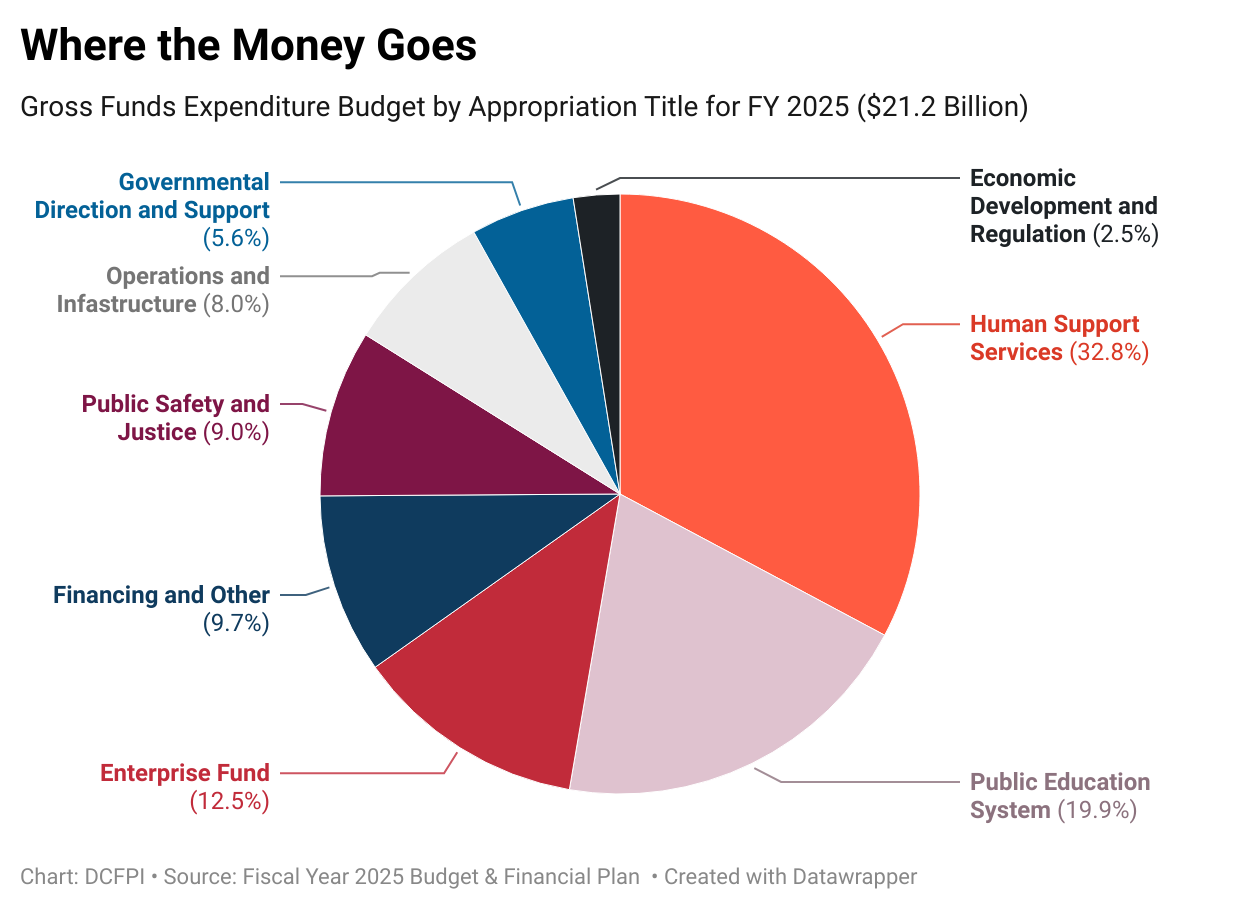

The biggest share of the operating budget goes to human support services, as it does in most other states’ budgets (Figure 1). This part of the budget provides programs that keep residents safe and healthy. The majority of the spending goes to health care programs that serve more than one-third of DC residents. Other services target youth, veterans, and the elderly.

The next biggest share of the operating budget goes to early education and public education, including the District’s traditional public schools and its public charter schools, as well as private school tuition for students who have special education needs that the public schools are not able to meet. The DC Public Library system is also included in this category.

Public safety and justice spending includes the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) and the Fire and Emergency Medical Services Department. The MPD regularly spends more than its approved budget, mostly because of personnel overtime. In 2022, DC Council passed the Budget and Staffing Transparency Amendment, requiring MPD to regularly publish staffing and budget data to increase transparency and public accountability.

Other spending categories, or appropriation titles, include:

- The Enterprise Fund, where the District deposits taxes and fees collected for special purposes.

- Financing, which includes debt service payments on major capital projects and other types of borrowing as well as DC government employees’ retirement.

- Operations and Infrastructure, which includes trash collection and transportation.

- Government Direction and Support, which includes many of the agencies that help manage, run, and support the general operations of the government, including the Office of the Mayor, the DC Council, CFO, and the Office of the Chief Technology Officer.

- Economic Development, which provides funding for affordable housing and workforce development through agencies including the Department of Housing and Community Development and the Department of Employment Services.

Where the District’s Money Comes From

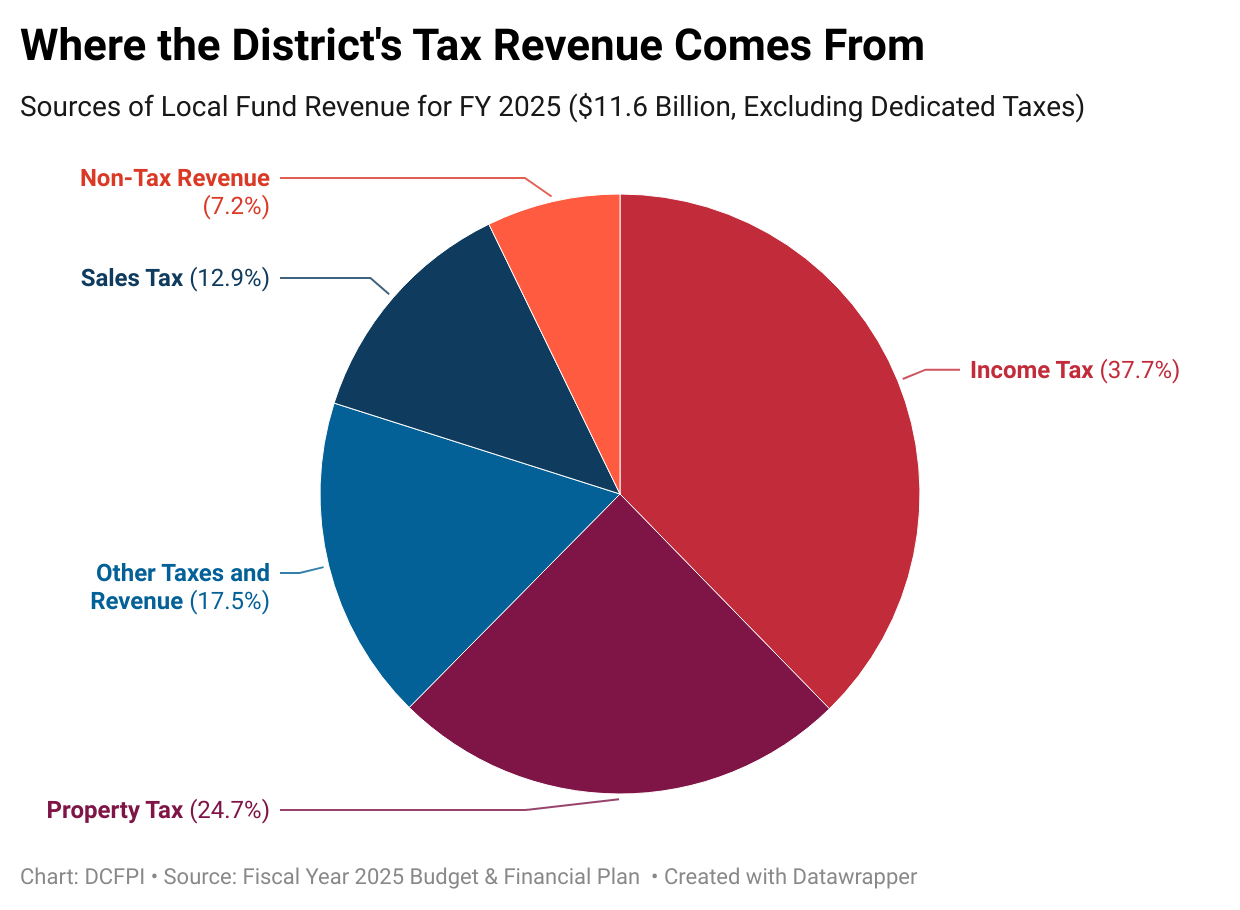

The largest sources of DC’s revenue are local taxes and federal funds (Figure 2). The three largest sources of local tax revenue are property, individual income, and sales and use taxes. Some taxes, known as dedicated taxes, can only be spent on specific activities. For example, all parking sales taxes are dedicated to the District’s annual funding responsibility for Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA). Enterprise funds include some dedicated taxes and user fees for quasi-government agencies such as DC Water and the Housing Finance agency.

Grants from the federal government account for about a quarter of DC’s revenue. DC receives many of the same grants that other states and cities receive, including cost sharing for Medicaid and the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program.

Without Statehood, DC is Denied Full Control Over its Budget

Because the District is not a state or located within one, it is in charge of many programs that a state would normally administer for its largest cities. These programs include Medicaid, unemployment insurance, and more. And while DC has more responsibilities than many cities, it has less autonomy over its budget and other laws than states do.

Every law passed by DC Council and signed by the mayor can be modified or rejected by Congress. After DC leaders approve the budget, Congress has 30 days to reject and change it. After that period, DC has the authority to spend its local funds as outlined in its budget. Congress also mandates a DC budget not only for the upcoming fiscal year, but for four years out through the financial plan.

Congress regularly interferes with how DC gets and spends its money. For example, in 2014, District voters approved a ballot initiative to legalize possession of a small amount of cannabis. But an annual congressional budget rider prohibits DC from spending money to regulate and eliminate penalties associated with possessing, using, or distributing recreational cannabis. It also means that the District is unable to tax recreational cannabis sales, thereby denying DC revenue that might be invested in Black and brown communities harmed by the racist War on Drugs.

How the Budget is Created

The mayor and DC Council decide how to allocate the District’s resources through the budget, with input from advocates and residents about what is important to them.

The mayor and DC Council decide how to allocate the District’s resources through the budget, with input from advocates and residents about what is important to them.

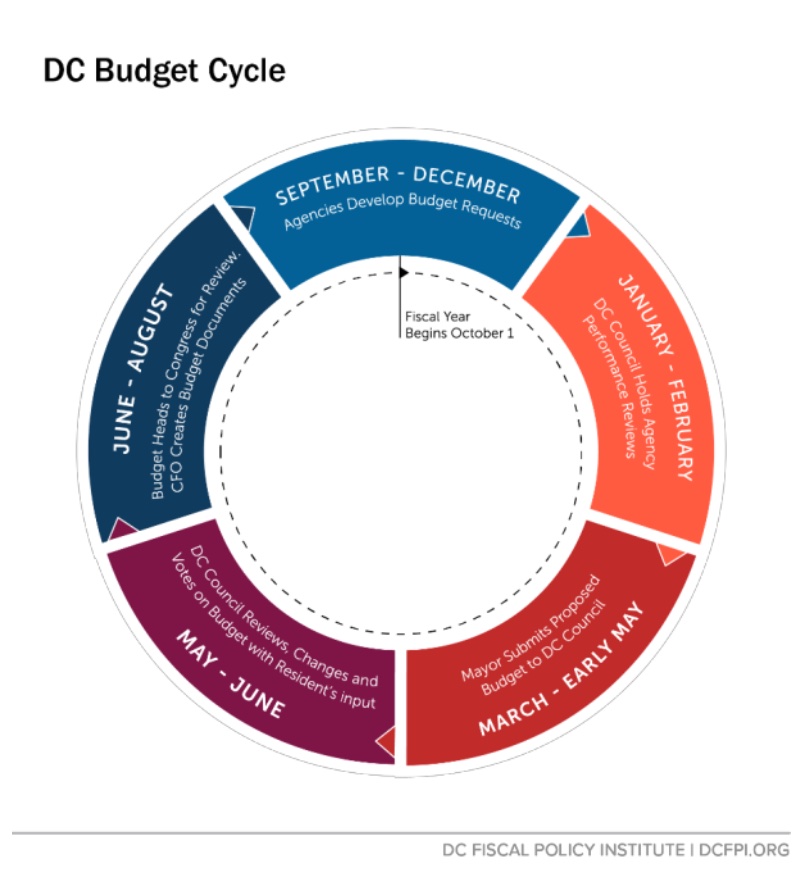

The DC budget operates in what’s known as a fiscal year (FY) that begins October 1 and ends September 30—the same fiscal year followed by the federal government. Most states, including Maryland and Virginia, begin their fiscal years on July 1. Each October, as the fiscal year is starting, DC officials begin planning for next year’s budget.

This is a process that includes agency budget requests, agency performance hearings, a proposed budget from the mayor, review, changes, and voting by the DC Council, and final approval by the US Congress. At the end of the budget formation process, the DC Chief Financial Officer (CFO) produces budget documents for each agency that help the agencies execute the new budget.

By law, the budget must be balanced, with expenditures at or below revenues (which can include, but is not limited to, revenue generated through taxes and fees and dollars pulled from savings). The DC Council can vote to change the mayor’s proposal—in terms of spending levels, revenue policy, and other policies included in the proposal. While the Council can cut spending in one area and allocate those savings in another area or raise revenue through taxes or other means to expand programs and services, the Council rules typically limit its committees’ spending targets to match those in the mayor’s proposal. This often leads to an outcome where Council adopts the majority of the mayor’s budget as proposed, and one where Council approves transformative investments outside of the committee process in the Committee of the Whole (similar to the full body of a state legislature).

There may be changes to the budget during the fiscal year for several reasons, including if the mayor uses their authority to repurposes small pots of funding, lawmakers tap the reserves to meet urgent needs, or if revenues are falling below expectations, for example. Every three months, the CFO forecasts how much revenue the District is projected to collect during the financial plan, and the mayor and Council may need to adjust spending throughout that time to stay in balance with the amount of money DC collects. A budget surplus can happen when 1) revenue collections are higher than expected, 2) spending is lower than expected, or 3) both. A budget gap occurs when revenue is less than expenditures.

A Closer Look at the Budget Process

September – December: Agencies Develop Budget Requests

CFO’s Role: The CFO calculates how much it will cost the District to maintain the current level of services and obligations, which is known as the Current Services Funding Level (CSFL). The CFO publishes the CSFL early in the fall and it serves as the starting point for virtually all agency budget requests.

Agency’s Role: Agencies provide the CFO with information needed to calculate the CSFL and, taking into consideration the mayor’s District-wide strategic plan, formulate their budget requests and submit them to the Office of Budget and Planning in December.

Mayor’s Role: The mayor’s office, through the Office of the City Administrator, gives each agency a spending target for local funds, which the agency’s operating budget request cannot exceed. This target number is often set below the current budget to encourage agencies to look for savings. Agencies develop budget requests that meet those targets but are also allowed to submit requests for targeted service enhancements or new initiatives.

January – March: DC Council Holds Agency Performance Hearings

CFO’s Role: In February, the CFO issues a revenue forecast, one of four issued during the year to project expected revenue collections for the current year and upcoming four years. When the mayor submits her local fund budget, she cannot propose expenditures that are greater than the CFO’s February revenue forecast unless she puts forward a proposal to raise revenue, such as through a tax or fee increase.

Mayor’s Role: The mayor’s budget review teams meet with each agency to review their budget requests. In particular, the mayor considers enhancements she will include, in alignment with projected revenues.. Budget adjustments can include policies to increase revenue, such as additional taxes or fees, or cuts and enhancements to spending.

DC Council’s Role: While the mayor is preparing a budget proposal, the DC Council starts holding performance oversight hearings on the performance of each agency, to review the agency’s operations and effectiveness in implementing its budget over the last year. The DC Council is divided into a number of committees, which have oversight over a set of related agencies. The Committee on Transportation and the Environment, for example, reviews the budgets of more than a dozen agencies, including the Department of Public Works, Department of Transportation, and the Department of Motor Vehicles.

Agency’s Role: The head of the agency is required to discuss the agency’s performance and expenditures in the past fiscal year and answer oversight questions from Councilmembers. Before each performance oversight hearing, each Council committee submits a detailed set of questions to the agencies they oversee. Those questions and the answers are posted on the DC Council website. You can contact the Council’s Office of the Budget Director, or the committee clerk for any committee of interest, if you need help finding these documents.

Residents’ Role: Residents are encouraged to testify at performance oversight hearings on how you see dollars being spent and make recommendations for improving how an agency operates and provides services. For example, if your neighborhood library has stopped purchasing new books, the oversight hearing is an opportunity to ask why. Residents can also suggest questions for the Council committee members to ask agency officials at the performance oversight hearing. You should contact a committee in January if you have questions that you would like them to submit to the agencies. DC Council committees, their chairperson and members, and the agencies they oversee can be found on the DC Council website by clicking “The Council,” then “Committees.”

March — Early May: Mayor Submits Proposed Budget to DC Council

Mayor’s Role: The mayor submits a proposed budget to the DC Council in mid- to late March, though she releases individual school budgets a month earlier, in February. Many of the mayor’s key budget decisions—whether to cut funds, increase funds, cut taxes, or raise taxes—are finalized in the few weeks before the budget is submitted. The mayor submits two proposed budgets for the upcoming fiscal year: the operating budget and a capital budget. She also submits a supplemental budget proposing mid-year changes for the current fiscal year.

DC Council’s Role: After the mayor’s budget is released, each Council committee holds budget oversight hearings on the portion of the budget the committee oversees where agency officials and the public are invited to testify. For example, the Committee on Housing holds hearings on the budget for the DC Housing Authority, Office of the Tenant Advocate, and the Department of Human Services, among others. As in the case in the performance oversight hearings held earlier in the year, each Council committee submits a detailed set of questions to each agency they oversee prior to the budget oversight hearings. Those questions and the answers are posted in the Budget Oversight page on the DC Council’s website. If you need help finding these documents you can contact the office of the DC Council’s Office of the Budget Director, or the committee clerk for any committee of interest. After the budget oversight hearings, each DC Council committee meets to markup the portion of the budget they oversee. The markup is the process through which the committees make changes to the mayor’s budget. While the committees can shift funds from one program to another or from one agency to another within their oversight area, under typical Council rules, they cannot propose spending more than the total amount in the mayor’s proposed budget for the agencies overseen by that committee, unless they receive a transfer of funds from another committee.

Residents’ Role: DC residents and advocates play an important role in shaping the DC Council’s budget decisions on how to alter the mayor’s budget request by testifying at budget oversight hearings about portions of the budget they like or do not like. Residents also meet with Councilmembers to encourage funding increases for programs that are important to them. You can contact Councilmembers individually, by calling or sending emails. You may also want to join a coalition that advocates on your issue.

May — June: Budget Gets Voted on and Sent to Congress

DC Council’s Role: In May, the entire DC Council votes on the Local Budget Act, the Federal Portion Budget Request Act, and the Budget Support Act. To do that, the entire Council meets to reconcile actions taken at the Committee level and to deal with any outstanding issues. Like all DC legislation, the budget has a second vote, or “second reading.” The second votes—on the Local Budget Act and the Budget Support Act—are held in late May or early June, and the final budget then is submitted to the US Congress for a 30-day review. The Council holds only one vote on the Federal Portion Budget Request Act, which Congress then incorporates into the federal budget.

Resident’s Role: DC residents and community leaders should continue to advocate for their budget priorities throughout the Council’s voting process. These last-minute efforts can make a big difference in the final budget.

DC’s Three Budget Laws

The Local Budget Act (LBA) sets the budget for each DC government agency and program. The LBA is limited in detail; it does not show program-by-program funding for each agency. That information is provided in companion budget documents.

The Budget Support Act (BSA) covers any budget changes that require a change in law, such as a tax change or a change in eligibility for a specific program. Sometimes initiatives that are not strictly related to the budget are placed in the BSA.

The Federal Portion Budget Request Act includes funds appropriated for the District for specific purposes, such as the federally operated DC court system.

How to Read Budget Documents

A general guideline for examining budgets is to see how they have changed from year to year. Look for big spikes and big declines. And ask, did costs jump or fall in one area? Why? When you compare budgets from year to year, make sure that you compare “apples to apples,” or similar categories of spending. Sometimes, for example, the general fund amount may change from year to year, but gross funds might remain the same because of an increase or decrease in federal dollars.

Let’s say you regularly use your neighborhood library and want to understand how much DC invests in the library system. What do you do? First, there are certain questions to find answers to: 1) What is the library system’s budget? 2) Did it get cut last year or did it increase? 3) How does the library system spend the money it receives?

These questions can be answered by looking at the library budget published on the Office of the Chief Financial Officer’s (OCFO) website. If you are looking for an answer between March and June, you’ll find information on the mayor’s proposed budget for the upcoming year, in addition to information on the current-year budget and last year’s. About a month after the budget is approved in June, the documents will reflect the final budget as approved by the DC Council for the fiscal year.

The OCFO provides budget documents for every DC agency. These are the city departments identified by the service provided: Department of Transportation, Fire and Emergency Medical Services, Department of Housing and Community Development, etc.

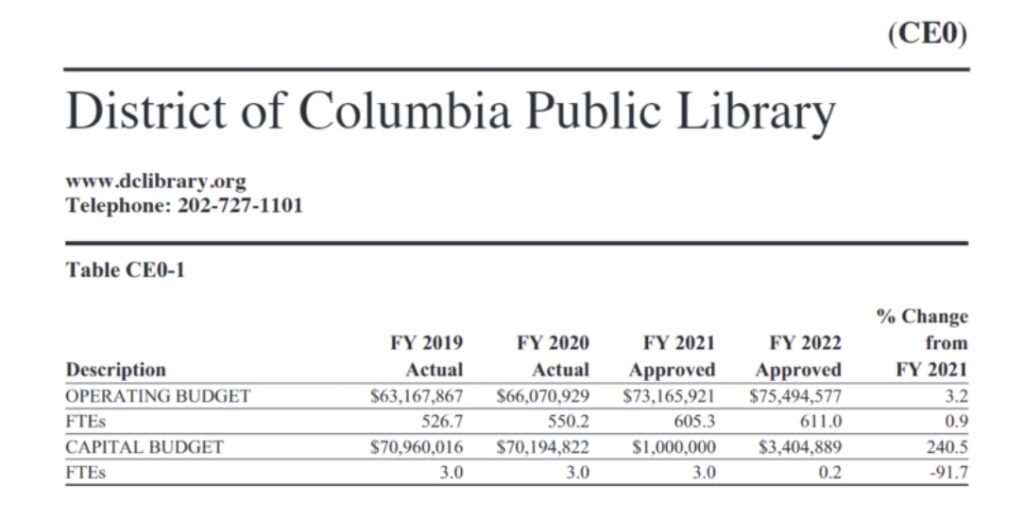

Let’s take a closer look at the agency budget chapter for the DC Public Library, using the Approved FY 2022 budget as an example. It is found under the Public Education System appropriation title. There are several key tables that show up in the budget chapter for every agency to help explain the agency’s funding trends. The title of each table also includes a three-letter code for the agency. The code for the DC Public Library is “CE0.” When you find the library chapter, you will see this table, CE0-1. What does it tell you?

The table shows the previous two years’ actual spending by the agency, and the number of workers at the agency (full-time equivalents, or FTEs). It also shows:

- The current year budget and FTEs (FY 2022 Approved); and,

- The percentage change in dollars and FTEs between the current year and next year.

FY 2020 reflects the actual dollars spent on the library system, based on the city’s annual audit of its books. FY 2021 denotes spending that has been approved, but not the actual spending number, which became available about a year later once the mayor released her proposed budget for FY 2023.

You see that the city spent $66.1 million on libraries in FY 2020. Approved funding increased by $7.1 million for FY 2021, to $73.2 million. For FY 2022, library funding increased 3.2 percent, to $77.5 million. These numbers have not been adjusted for inflation. As a library advocate, you might be curious as to why the additional money was allocated. Before answering that question, it’s helpful to know where the additional money comes from in the first place.

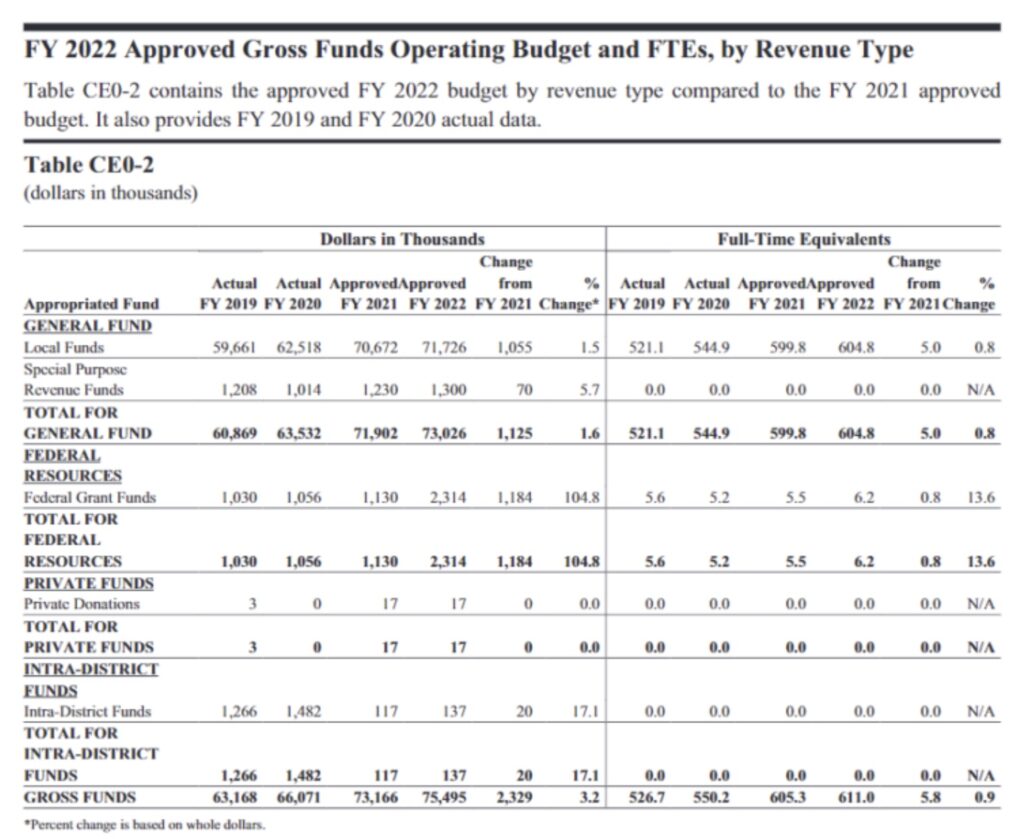

Table CE0-2 shows the sources of library funding, including the possible streams of revenue: local, special purpose, federal, private, and Intra-District funds. For the DC public library system, a majority of funding comes from local tax dollars, which you can see by looking at the Total General Fund line. Total general fund support was $63.5 million in FY 2020, and federal funding was $1.1 million. Note that the mixture of funds varies from agency to agency. Federal dollars are more available for certain programs in human services, for example, than for public works.

How does all this library funding get spent? Table CE0-2 also shows how many full-time equivalent positions (FTEs) in the Library System are funded by various revenue sources. Table CE0-2 shows, for example, that 544.9 positions were funded with general fund dollars in FY 2020. FTEs include librarians and other staff.

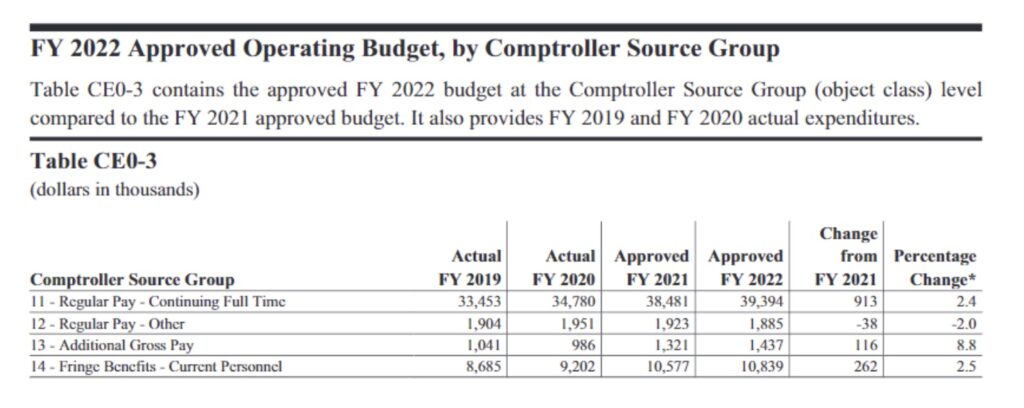

The next chart, Table CE0-3, details spending by personal services and nonpersonal services. Personal services include associated with employees. Nonpersonal services include the costs of office supplies, rent (if the agency rents space), contracts for services, etc.

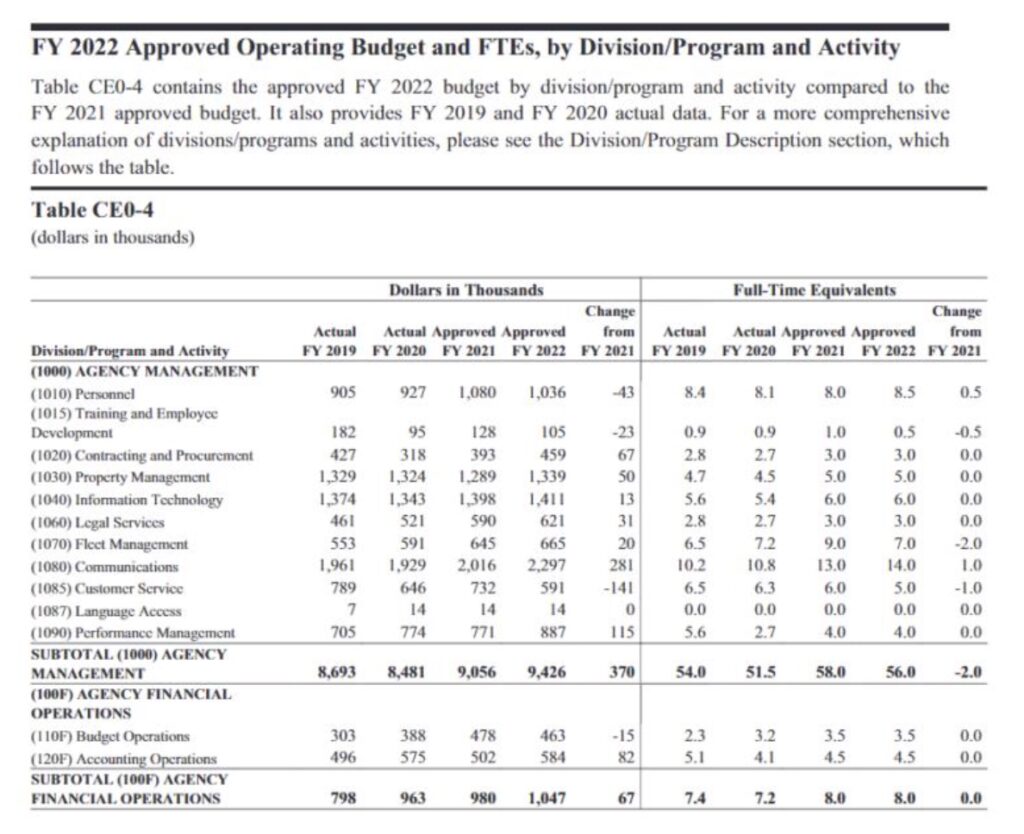

Next, table CE0-4 examines the agency by what is known as the program and activity level. These are the detailed line items that show how the library’s budget is spent.

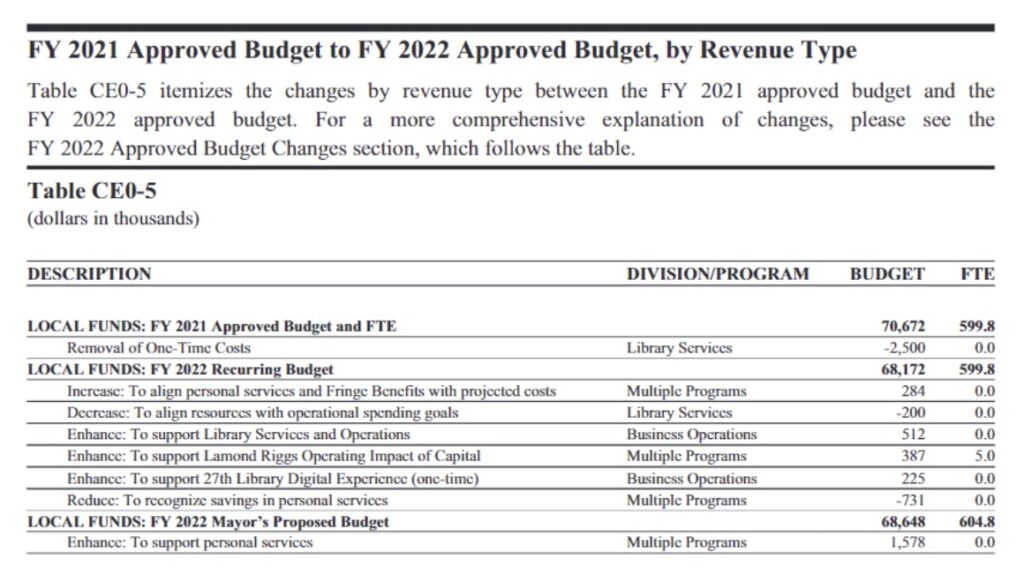

Now say you want to know whether any new neighborhood libraries will open. That question is answered in Table CE0-5 and the accompanying narrative, Agency Budget Submission. This section describes the major changes proposed in the budget. Sometimes the explanations are very clear, and sometimes they’re not. If you have questions, you might consider making a call or sending an email to the DC Council committee that has oversight over a particular agency.

At the end of the agency budget documents are various performance measurements that seek to assess how well the agency is delivering services. They also contain general facts about the agency, such as how many books were circulated in the library system that year. The performance information for some agencies is better than for others. Pushing for better measures is an important role that residents can play.

Other Budget Resources

DC’s Budget & Financial Plan

The OCFO’s budget page contains links to the current budget, the current services funding level baseline budget, and an archive of prior year budgets dating back to FY 2007.

www.cfo.dc.gov/budget

Quarterly Revenue Forecast

Four times a year, in February, June, September, and December, the OCFO issues a revenue forecast for the current fiscal year and next four fiscal years. The February revenue forecast sets the groundwork for the mayor’s proposed budget.

www.cfo.dc.gov/page/quarterly-revenue-estimates

Budget and Performance Oversight Resources

The DC Council website posts the questions posed by each Council Committee to agencies as part of the performance and budget oversight hearings, as well as the agencies’ answers.

https://dccouncil.gov/budget-oversight-2023/

Committee Reports

Each DC Council Committee prepares a report on their agency budgets. The reports are available online on the Council’s website.

https://www.dccouncilbudget.com/fiscal-year-budgets

CFO Info Interactive Dashboard

The CFO Info page is an interactive web-based budget and expenditures dashboard. In addition to viewing each agency’s budget in depth, users can filter by fund and expense type.

http://cfoinfo.dc.gov/

DC Council Committee Staff

Get to know them and don’t be afraid to ask them questions and use their resources.

www.dccouncil.us/committees

Glossary

Agency: Division of city government in charge of service delivery, such as Department of Public Works.

Appropriation titles: The seven clusters in which DC agencies are grouped together based on their general function.

Current Services Funding Level (CSFL): Amount of funding needed to maintain current services.

Dedicated tax: A tax whose revenue is directed for a specific purpose.

Financial plan: Budget for the city’s current fiscal year and three years beyond. The four-year financial plan is mandated by Congress.

Full-time equivalent (FTE): One or more employment positions in which the combined work is equal to one full-time year-round worker (40 hours and 52 weeks).

Gross funds: Combines all the sources of funding, including the General Fund, federal funds, and any private dollars.

Intra-District funds: An accounting mechanism to track payments for services provided by one District agency on behalf of another District agency.

Markup: Changes to legislation or the mayor’s budget proposal made by a DC Council Committee.

Nonpersonal services: In an agency budget, includes costs not associated with employees, such as contracts for services, office supplies, and rent.

Revenue: The annual income or receipts of the District from all sources, including taxes, fees, grants, and investments.

Surplus: A budget surplus occurs when revenue exceeds what the government spends. DC law requires that any budget surplus automatically goes to the Housing Production Trust Fund and the Pay-As-You-Go Capital account, after replenishing the District’s four reserve accounts.

[1] All FY 2022 budget figures in this appendix are from Fiscal Year 2022 Budget & Financial Plan. See https://dcgov.app.box.com/s/5sz8y3wequcgtxqjfxsquqam8bpivy5m