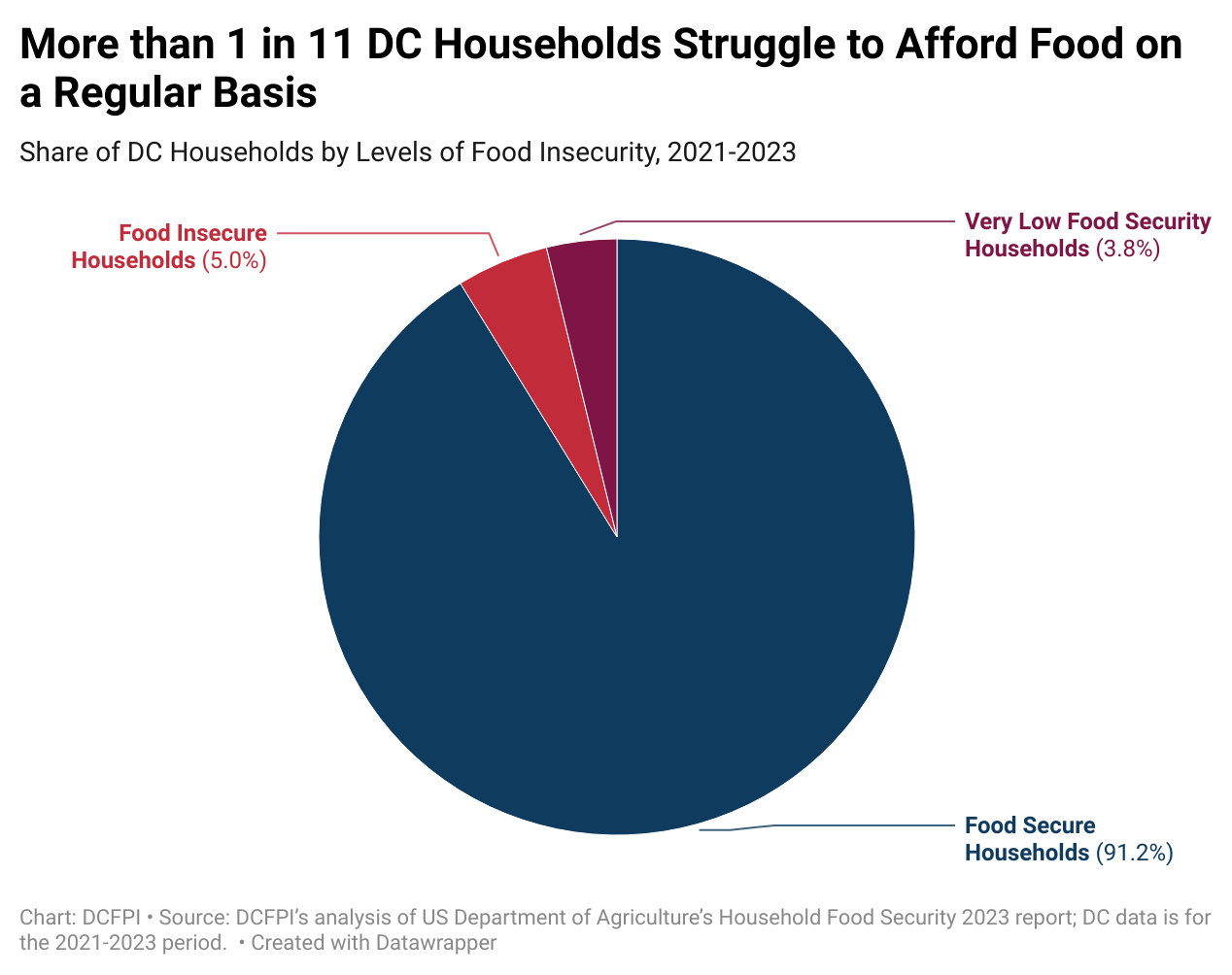

The Thanksgiving holiday is a good reminder that DC’s economic recovery is continuing to elude many families who struggle to afford the basics, including food and housing. More than 30,000 District households—or 8.8 percent—didn’t have enough nutritious food to eat on a regular basis between 2021 and 2023, on average, due to limited funds and access to food, according to a recent United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) report. Rising food prices, low incomes, and expiring pandemic aid are making it difficult to afford food in DC. High rates of food insecurity shows that DC lawmakers should protect and improve upon policies that help families afford a healthy diet.

A home faces food insecurity if its members don’t have access to enough healthy and nutritious food to support an active and healthy lifestyle. Some households face extreme levels of food hardship to the point where they skip meals due to a lack of resources, and they are considered to have “very low” food security. In DC, of the households who experienced food insecurity during the 2021-2023 period, 3.8 percent of them faced very low food security (Figure 1). While DC’s food insecurity rate was lower than the national average during this period, DC’s rate has not statistically improved in any three-year period looking back to before the pandemic began. This bucks national trends where there has been a rise in food hardship.

DC’s food security rates may be holding steady despite an uneven economic recovery and faring better compared to other states due to a combination of greater DC investments in economic security programs during the pandemic, administrative efforts to make it easier for residents to maintain food supports, and an increasing minimum wage.

USDA does not present state-level data by race, but nationally, Black, Latino, and Native American households experienced rates of food insecurity at least twice as high as white and Asian households in 2023. Food insecurity rates in DC and by race reflect structural barriers rooted in systemic racism, government-endorsed discrimination, and wealth and income inequities, all of which make it harder for many Black and brown residents to afford and access nutritious food.

DC families living with strapped budgets—who are disproportionately Black and brown—must make difficult choices, including trade-offs between the quality and amounts of food they purchase and other necessities like housing, health care, and child care. Since last September, food prices increased by 3 percent in the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria area and median rent prices jumped 12 percent (the highest jump among the country’s largest metropolitan areas). These increases are occurring as DC’s progress against poverty is stalling and as pandemic food supports have expired. The combined effects of these trends may show up in UDSA’s food insecurity rates in next year’s report.

Lack of food access for low to moderate income households is also shaped by place and where food markets and grocery stores are located. For example, of the 49 full-service grocery stores in DC, just two are located in Ward 7 and one is located in Ward 8, which are predominately Black and of low-income. For comparison, Ward 3—a predominately wealthy and white ward—has 11 full-service grocery stores. The Council has attempted to boost food access through the expansion of the Supermarket Tax Exemption Act of 2000, which provides a tax break for grocers operating in food deserts but has failed to adequately spur full-service grocery store construction in food-insecure neighborhoods. The Council also passed a temporary measure to increase Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits to DC residents, but the expansion expired in September 2024.

The DC Council should restore the SNAP increase and deepen efforts to bring more food options to Wards 7 and 8 to better ensure that all residents have enough food on their plate year-round.