Nick Johnson is a consultant to DC Fiscal Policy Institute and a senior fellow at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. He served as executive director of the DC Tax Revision Commission from 2022 to 2024.

Despite benefiting from DC’s publicly funded services including mass transit, roads, and public education, some businesses operating in the District do not contribute to the District’s shared resources through its primary business taxes. Because DC is not a state, certain businesses including major law firms, lobbyists, and consulting firms, are able to leverage a major federally-imposed loophole to avoid paying business tax. But a new, simple, broad-based value-added tax, called the Business Activity Tax (BAT), would make business taxation fairer and more racially equitable while raising significant revenue for the District. The revenue raised by the new tax could reduce other taxes paid by businesses, fill in the gaps of declining sources of revenue to fund programs that help grow an inclusive economy, or some combination of the two.

The District uniquely exempts from taxation many law firms, most of which are white-owned, and other professional services firms who are profiting immensely from doing business here. These businesses are set up as partnerships to pass their profits on to their owner(s), who then report it as income. The exemption results from a 1979 appeals court ruling that the federal Home Rule Act bars the District from taxing such businesses’ incomes if the owners live outside of the District, because doing so would be an impermissible tax on their personal incomes.[1] By contrast, other states can tax nonresident owners’ income if they choose to, and do so, as a matter of course.

A BAT would resolve this issue, and as envisioned in this report would:

- Complement existing franchise taxes, rather than adding to them or replacing them, so that it would affect only businesses that now pay little or no tax.

- Exempt the first $200,000 of economic activity from tax, benefiting the District’s small businesses.

- Broaden DC’s base of business taxation while leveling the playing field, compared with other options.

- Not create incentives for businesses to move out of the District, both because of how the tax is structured, and because lawmakers could use revenue from the tax to make the District more economically competitive.

- Make DC business taxes more racially equitable because most of the unpaid business taxes foregone due to loopholes are from well-heeled, white-owned businesses.

Revenues from the BAT would be substantial. A 2 percent BAT rate could raise $500 million in fiscal year (FY) 2026. Lawmakers could use these funds to replace declining revenue sources like commercial property in order to maintain or expand investments in residents, workers, and communities with low incomes for more broadly shared prosperity. Lawmakers could also use BAT revenue to replace or at least reduce the sales tax increase and/or the payroll tax increase that lawmakers enacted in the FY 2025 budget.

Contents

- DC is Denied the Ability Held by Other States and Major Cities to Tax Profitable Professional Services Firms

- DC’s Franchise Tax Loophole Also Enables Corporations to Minimize Taxable Income and Shield Profits from Taxation

- A Business Activity Tax Would Collect Revenue from Businesses that Pay Little or No Franchise Tax

- A Business Activity Tax Will Broaden DC’s Business Tax Base While Leveling the Playing Field Between Businesses

- A Business Activity Tax Would Have Minimal Impact on Business Location Decisions

- A Business Activity Tax is Allowable Under the Home Rule Act

- A Business Activity Tax Will Make DC Business Taxation Fairer and More Racially Equitable

- The New Hampshire Experience: Significant Revenue, Minimal Economic Disruption

A Business Activity Tax Would Improve the District’s Bottom Line and Help the Economy Thrive

- A Business Activity Tax Would Generate Significant Levels of Revenue

- Revenue Could Potentially Reduce or Replace the Tax Increases Enacted in the FY 2025 Budget

- BAT Revenue Can Replace Lost Revenue and Sustain Services

Appendix 1: Additional Examples of How the BAT Would Affect Entity-Level Business Taxes

DC’s Current Business Taxes Leave Loophole that Allow Some to Avoid Contributing to Shared Resources

Currently, DC’s main form of business taxation is the business franchise tax. It is the primary way that businesses directly contribute to the shared public resources that support the robust DC economy in which they operate. The District has both a:

- Corporate franchise tax, for businesses structured as corporations (including S corporations that are not subject to federal corporate income tax), and

- An unincorporated business (UB) franchise tax, for businesses structured as something other than a corporation, like a limited liability company, partnership, or a sole proprietorship.

That means that all kinds of businesses, from major multinational corporations to mom-and-pop stores, may owe franchise tax; DC calculates the tax at 8.25 percent of the business’s profits earned in the District.[2]

These franchise taxes are an important source of revenue for the District and help pay for public services that benefit businesses and their owners, employees, and customers. In 2024, franchise taxes provided $1.1 billion or about 9.5 percent of general revenues, an amount greater than the local-funds expenditures for any DC agency or department outside of the school system.[3]

But not every prosperous business pays DC’s franchise tax. Major categories of DC businesses pay little or no franchise tax while reaping significant benefits from public services in the District. These include professional services firms and corporations that have profits but little taxable income.

DC is Denied the Ability Held by Other States and Major Cities to Tax Profitable Professional Services Firms

The District’s UB franchise tax applies to many small and large businesses, from child care facilities to consulting firms to landlords. But it does not apply to some of the District’s most profitable unincorporated businesses: law firms, lobbying agencies, accounting firms, and the like, if they are organized as partnerships. Thanks to this federal limitation, about one-third of mid-sized and large DC businesses with gross receipts over $5 million are exempt from the UB franchise tax.

The reason is rooted in the federal 1973 Home Rule Act. This law gave the District the power to levy taxes, including income taxes, but it barred the District from taxing the “personal income” of nonresidents.[4] The main purpose of this provision was to shield suburban commuters from the DC income tax, and the consequence has been to deprive the District of much-needed income tax revenue to invest in people, communities, and the economy that so many outside of DC benefit from.

In 1980, a divided federal appeals court—overruling the decision of a trial judge—ruled that the ban on taxing nonresidents’ incomes doesn’t just apply to wages. In Bishop v. District of Columbia, the court ruled that the ban also applies to the profits earned by many businesses that—because they are legally structured as partnerships—are passed through to partner-owners, such as law firms and accounting partnerships, if their owners don’t live in the District. The reason, said the court, is that those profits flow through to those nonresident owners as personal income.[5] As a result, lawmakers changed the District’s UB franchise tax to exempt professional services partnerships, although it applies to other types of unincorporated businesses.

Such businesses are not automatically exempt from the DC Ballpark Fee—a sliding-scale levy on businesses whose DC gross receipts exceed $5 million. The Office of Revenue Analysis reports that of the 2,577 businesses who were subject to the ballpark fee in 2020, 827 (or 32 percent) filed neither corporate nor UB franchise tax returns, likely because they were exempt under the Bishop ruling.[6] Given the large presence in DC of unincorporated professional partnerships like law firms, lobbyists, and consultants, this represents a significant gap in the DC tax base.

Other states and major cities do not experience this problem. They collect taxes from law firms, accounting agencies, and other kinds of businesses that are operating within their boundaries regardless of where the partners live. For example, Maryland and Virginia collect tax from law firms whose partners live all over the country—including those living in the District. (The partners can claim a credit for those taxes against the taxes where they live, so they are not double-taxed.)

It’s worth emphasizing that, on net, the benefits of this federally imposed loophole accrue entirely to nonresidents—that is, to people who live in Maryland, Virginia, or another state. DC residents do not benefit from this loophole because they must pay individual income tax on partnership earnings.[7] (If they did pay the franchise tax, they’d be entitled to exempt their partnership earnings from the income tax.)

DC’s Franchise Tax Loophole Also Enables Corporations to Minimize Taxable Income and Shield Profits from Taxation

The corporate franchise tax is nominally a tax on profitable corporations, but not all profitable corporations pay it. That’s because the corporate franchise tax is calculated based on the same limited definition of net income that the federal government uses for the federal corporate income tax, which allows for tax avoidance. While taxable net income as defined by the federal tax code is conceptually similar to profit—i.e., revenue minus expenses—in reality it is not the same. National studies show that many corporations that have significant profits report little or no taxable net income. One study identified 23 Fortune 500 companies that reported profits to their shareholders in every year from 2018 to 2022 but paid zero federal corporate income taxes in any of those years, and another 109 major corporations that paid zero federal corporate income taxes in at least one of those years.[8]

Many of those major corporations that don’t pay federal corporate taxes do business in the District. Since the District mostly follows federal law when it comes to calculating tax, it’s likely that they pay about as big a share of their profits in DC taxes as they pay in federal taxes—not very much, if anything. There are not publicly available data that would allow confirmation on whether those or other profitable corporations paid DC’s corporate franchise tax, but data from the Office of Tax and Revenue shows that some of the same provisions that allow profitable corporations to avoid federal taxation also allows them to avoid DC taxes. For example, federal tax law that the District also follows allows corporations to write off the costs of investments in equipment more quickly than the equipment wears out and loses value; the DC Tax Expenditure report estimates that the District loses millions of dollars in revenue each year due to this accelerated depreciation and expensing.[9]

A Business Activity Tax Would Ensure Businesses Pay Their Fair Share of Taxes and Expand DC’s Tax Base

The District should ensure that all or most DC businesses pay their fair share and contribute to the cost of providing public services by enacting a Business Activity Tax (BAT)—a simple, low-rate “value-added tax” on the economic activity of businesses in the District. A value-added tax or VAT is a tax assessed on the value added in each production stage of a good or service. Such taxes are widely used around the world; many economists favor them because they tax a wide range of economic activity, unlike the narrower franchise tax focused on profits, while avoiding taxing the same transaction twice.

The DC Tax Revision Commission, which develops recommendations for changes to DC’s tax system, considered a BAT during its appointment from 2022 and 2024. The version of a BAT considered by the Commission has considerable merit, for several reasons:

- The tax would mostly affect businesses that are not already paying franchise tax, including the professional services partnerships that the federal government now prevents the District from taxing.

- Small businesses—those with less than $200,000 in revenues—would be exempt.

- A much lower rate would be applied to business activity than the current 8.25 percent franchise tax rate, while still raising significant revenue, in part because of the broadened number of businesses paying the tax (the broadened base).

- A BAT is consistent with the Home Rule Act.

- There is evidence from other states that the tax can raise significant revenue with minimal economic effects.

- A BAT is preferable to other forms of business taxation, like a gross receipts tax or the recently expanded payroll tax, as explained below.

A Business Activity Tax Would Collect Revenue from Businesses that Pay Little or No Franchise Tax

Under a BAT, total business activity would be defined as the difference between a business’s annual gross receipts (all money from all sources) and what it pays to other businesses. Only the amount of activity above a threshold amount would be subject to tax, which DCFPI proposes be set at $200,000 initially, as recommended by the DC Tax Revision Commission. That threshold should be adjusted annually for inflation each year thereafter, as done in New Hampshire (described more fully below). This would exempt the smallest businesses from the tax entirely, and it would reduce taxable activity for all other businesses. Multiplying the resulting amount by a tax rate would determine the amount of tax.

The formula would be:

Tax liability = (Gross receipts minus purchases, rent, royalties, and capital investments minus $200,000) times the tax rate.

Since the goal of a BAT is to collect revenue from businesses that are currently paying little or no franchise tax, the BAT should be allowed as a dollar-for-dollar credit against the corporate franchise tax, the UB tax, or the individual income tax. That means that businesses that already pay significant DC franchise tax would not experience a tax increase. Businesses could also claim the BAT as a federal tax deduction because it is a business expense.

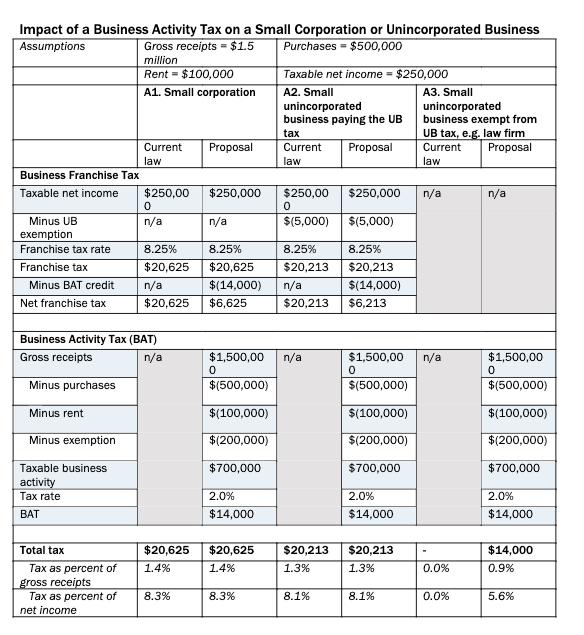

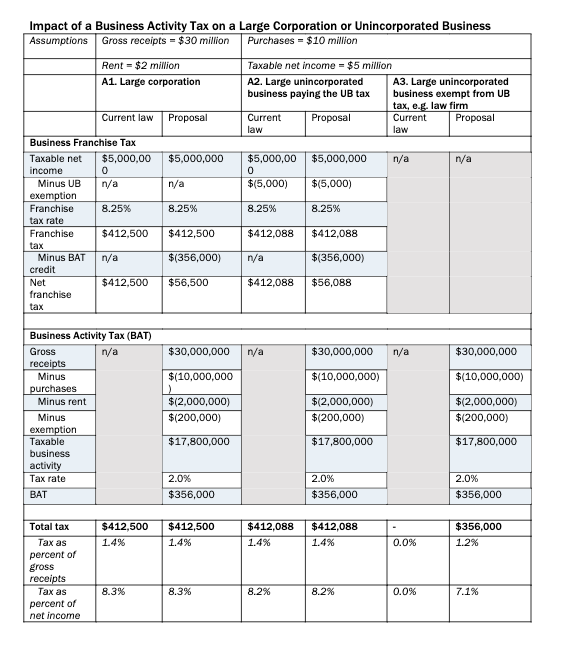

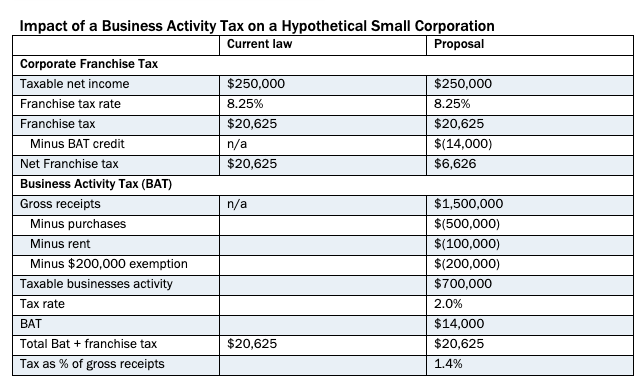

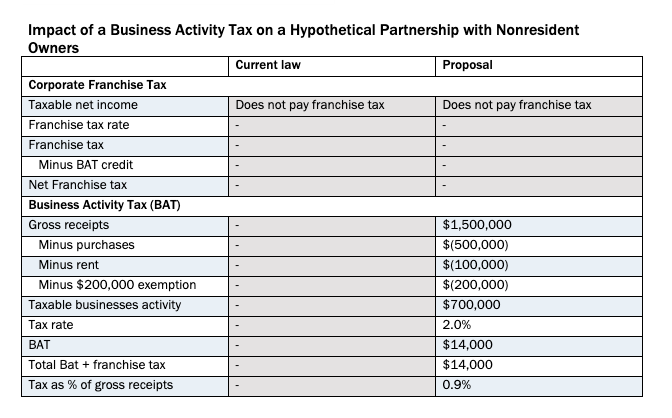

Table 1 provides an example of how a 2 percent BAT might affect a hypothetical small corporation with $1.5 million in gross receipts and $250,000 in net income. Under current law, the corporation pays a $20,625 franchise tax on its income. Under the BAT, the corporation pays a $14,000 BAT on its business activity but can claim that as a dollar-for-dollar credit against its franchise tax, resulting in no change to its tax liability.

Table 2 shows why a BAT increases the fairness in the system: a professional services business with exactly the same levels of gross receipts and net income as the business described in Table 1, structured as a partnership instead of as a corporation, pays no franchise tax at all under current law when its owners live outside of the District. A BAT would not fully equalize the two businesses, but it would reduce the differential by more than half. (Appendix 1 shows additional examples of how the BAT would affect entity-level business taxes.) Table 2 shows why a BAT increases the fairness in the system: a professional services business with exactly the same levels of gross receipts and net income as the business described in Table 1, structured as a partnership instead of as a corporation, pays no franchise tax at all under current law when its owners live outside of the District. A BAT would not fully equalize the two businesses, but it would reduce the differential by more than half. (Appendix 1 shows additional examples of how the BAT would affect entity-level business taxes.)

A Business Activity Tax Will Broaden DC’s Business Tax Base While Leveling the Playing Field Between Businesses

In the fiscal year (FY) 2025 budget, the District took a different approach to expanding what businesses pay to the District by increasing the rate of the DC payroll tax to bolster general fund revenue.[10] The payroll tax has broad reach like the BAT in that nearly every DC private-sector employer, large or small, for-profit or nonprofit, pays the tax. But rather than ensure that all firms with business in the District pay their fair share of taxes, the payroll tax applies the same to those that currently do and don’t pay the business franchise tax (or whose owners pay income taxes) to the District.

In fact, there are several important differences between the two taxes. One is that the payroll tax, unlike the proposed BAT, cannot be claimed as a credit against the corporate or UB franchise tax. Another difference is that, for a multistate business, payroll tax liability is based on where employees’ work is located, while BAT liability is based on where business’ sales are delivered through a calculation already used in DC known as the “single sales factor” formula. And the BAT proposed in this report exempts $200,000 in gross receipts from the tax (leaving some small businesses owing zero BAT) while the payroll tax is applied to the first dollar of wages paid even for the smallest enterprise.

Some states or localities broaden their business tax base with a gross receipts tax. Virginia suburbs, like several other states, do this. Gross receipts taxes, unlike the BAT, do not allow subtractions for purchases. Economists generally prefer value-added taxes over gross receipts taxes because they are economically neutral. That is, they treat similar economic activity similarly, without favoring particular organizational structures.[11] Economic neutrality reduces the incentive for businesses to waste resources by rearranging their affairs to minimize tax liability. For example, if a business buys a service (say, tech support) from a local vendor, gross receipts tax is paid on the transaction, but if the business handles the service in-house, it avoids the tax. Business organizations also have expressed opposition to gross receipts taxes. In a June 2024 letter to the Tax Revision Commission, the DC Chamber of Commerce drew a distinction between the proposed BAT—for which it offered qualified support—and gross receipts taxes that are common in other states. The Chamber of Commerce wrote:

“The New Hampshire Business Enterprise Tax […] offers benefits that may be particularly well-suited to the District. It is notably less problematic than far more complex and economically disruptive gross receipts taxes such as the Ohio commercial activities tax, the Texas margin tax, the Nevada commerce tax, and the Washington State business and occupation tax.”[12]

A Business Activity Tax Would Have Minimal Impact on Business Location Decisions

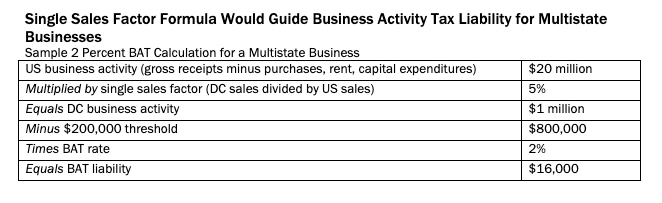

A BAT would apply to a business’s economic activity associated with the District—not to its payroll or property in the District. The distinction is subtle but important. For a business operating across multiple states, as many do, the portion of their economic activity subject to the District’s tax would not be based on how many DC employees they have or how much DC property the business has. Rather, multistate entities would determine their DC tax liability using the same single sales factor formula that is now used to determine income and franchise tax liability. Under this rule, a multistate firm’s DC taxable activity is calculated by dividing its DC sales by its nationwide sales and multiplying the result by its nationwide activity (or tax base, which means profit in the case of the corporate franchise tax and value-added in the case of a BAT.)

For example, if a multistate business attributed 5 percent of its US-based sales in DC, and had $20 million in national business activity, then it would have $1 million in taxable DC business activity. With a BAT rate of 2 percent on DC business activity in excess of $200,000, the business would pay $16,000 (Table 3).

Moreover, even a business that, for whatever reason, chooses to relocate its physical presence out of the District might not see an impact on their BAT liability. Depending on the choice of an apportionment rule, a professional services business that moves out of the District could still be subject to a BAT if it still has DC clients. BAT liability under a single sales factor rule would typically reflect where a firm’s clients are located and not where the provider of the services is physically located. Specifically, for sales of professional services or other services, a DC sale is generally one where the service is delivered to a DC address. So, moving out of the District would not be an effective strategy for minimizing taxation.

And this doesn’t account for the ways that the revenue from a BAT could be used to make DC more attractive to businesses through investments like state-of-the-art mass transit, well-maintained roads and infrastructure, and a stronger early education and school system. More broadly, business taxation generally does not drive firm location decisions. Businesses must weigh rental expenses, workers’ commuting costs, proximity to clients, and a host of other factors. Compared with those factors, the BAT’s low rate means that it is highly unlikely that it would spark businesses to relocate. Evidence from the implementation of other taxes in DC, such as the Ballpark Fee and analogous taxes in other states, bear this out.

A Business Activity Tax is Allowable Under the Home Rule Act

If the BAT was an income tax, as the franchise tax is, imposing it on professional partnerships’ incomes for non-resident partners would run afoul of the Bishop ruling. But the BAT is different. In a memo submitted to the Tax Revision Commission, Professor Peter Enrich of Northeastern University Law School, a noted expert in the field of state and local tax policy, explained why the courts are unlikely to extend the Bishop prohibition to the BAT:

“The BAT … is not in any sense a tax on the net income of either the business or its owners. Thus, a court following the analysis in the Bishop case would have little ground for finding a similar limitation on the reach of the BAT. A tax on a business’s overall economic activity is very different from a tax on the business’s profits. A value-added tax like the BAT takes as its tax base the total value of a business’s participation in the economy; the question of whether the business makes a profit, or of how large or small that profit may be, has no bearing on this measurement of economic activity. The BAT imposes a tax based on what the business actually does, rather than on what gain its partners or owners derive from that activity. This is particularly evident in the subtraction method’s calculation of the tax base, which starts with the gross proceeds of the business as a first measure of business activity, and then subtracts those aspects of the business’s costs that represent economic activity (value -added) already attributed to the business’s suppliers. Net income plays no part in this calculation.

“In short, the BAT will be a tax on the economic activity of the business, rather than a tax on the profits of its owners. It would take a surprising extension of the Bishop court’s interpretation of the Home Rule Act’s prohibition to bring the BAT within the prohibition’s scope. Thus, a major virtue of the BAT is that it will offer the District a business tax that is far more uniform, far more equitable, and far broader in its reach than the current business tax system.”

Source: Peter Enrich, “Memo to the DC Tax Revision Commission on the Proposal for a Value-added Based Business Activity Tax,” January 1, 2024, pages 2-3.

A Business Activity Tax Will Make DC Business Taxation Fairer and More Racially Equitable

A robust, fair system of business taxation is crucial for the overall resilience and equity of the tax system. As the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development points out, the District is an “economic engine” for the region and provides entrepreneurial opportunities for many people who live in the metropolitan area.[13] In the case of the professional service firms operating in DC that do not pay DC’s primary business taxes, many of them are profitable because of what the District uniquely offers them—access to the federal government. DC’s infrastructure, public transportation, highly educated workforce, institutions of education, and robust amenities and nightlife all support their success in attracting and retaining workers and running successful operations.

A BAT would ensure that those firms also contribute to the success of DC’s economy by broadening DC’s tax base, which improves resilience to downturns and economic shifts and shocks (e.g., remote work) and spreads the business responsibility for supporting DC’s public investments. Right now, DC residents who run businesses here bear a disproportionate responsibility for DC’s business contributions to revenue, even as the services and amenities are enjoyed by a much broader set of business owners.

The BAT can also improve the racial equity of DC’s tax system. There are far fewer Black-owned businesses in DC, relative to the overall population of Black residents, than white-owned businesses. Black-owned businesses also tend to be smaller.[14] In particular, DC has very few Black-owned law firms; in the District, 3.9 percent of the partners at major law firms are Black and 2.6 percent are Latinx.[15] That means that currently, the majority of the unpaid business taxes foregone due to the federally imposed loophole are from white-owned businesses. It also means that much of the revenue from the BAT would come from white-owned businesses with owners that thrive off the District’s economy but live in neighboring suburbs or multistate businesses not owned by District or metro area residents at all. If the revenue from the BAT were used broadly to help all locally-owned businesses and the broader community thrive, the net effect would be positive for racial equity in the District.

The New Hampshire Experience: Significant Revenue, Minimal Economic Disruption

A BAT is not a new concept in the District, nor would it be unique. The 1998 Tax Revision Commission proposed a value-added tax but did not adopt it, Michigan had a similar tax in the past, and many countries have value-added taxes.

The closest analogue to the BAT proposed in this paper is in New Hampshire, where it is known as a Business Enterprise Tax (BET). A rate of 0.55 percent is assessed on taxable enterprise value, which is the sum of all compensation paid or accrued, interest paid or accrued, and dividends paid by the business enterprise. The Tax Revision Commission conducted a series of interviews with New Hampshire elected officials, tax administrators, and outside experts and found:

- The New Hampshire BET is largely uncontroversial, with widespread bipartisan support. There is no evidence it has affected business location decisions.

- The New Hampshire BET is a simple tax, and because of the way it’s structured, there are few incentives to play games with it through avoidance. When violations do occur, they are typically the result of honest mistakes or good-faith ignorance about the tax because it is unique. For taxpayers, the BET is easy to comply with. All the elements are drawn from federal tax forms that businesses already fill out.

- The New Hampshire BET is a stable and effective way to raise revenue, and it captures a larger economic base than the state’s corporate income tax. In a state with annual private-sector Gross Domestic Product of $100 billion, the BET’s base is about $40 billion. (For comparison, private-sector GDP in the District is $120 billion.[16]) The base has grown more slowly than the corporate income tax, but it is less susceptible to year-over-year swings.[17]

A Business Activity Tax Would Improve the District’s Bottom Line and Help the Economy Thrive

A BAT is a promising revenue source at a time when the District’s economy appears to be changing. These revenues could help sustain public services at a time when landlords and tenants in downtown office buildings are paying less in tax, and/or they could be used to replace revenue from the new payroll tax, or the sales tax increase, which will hit low- and moderate-income residents hardest.

A Business Activity Tax Would Generate Significant Levels of Revenue

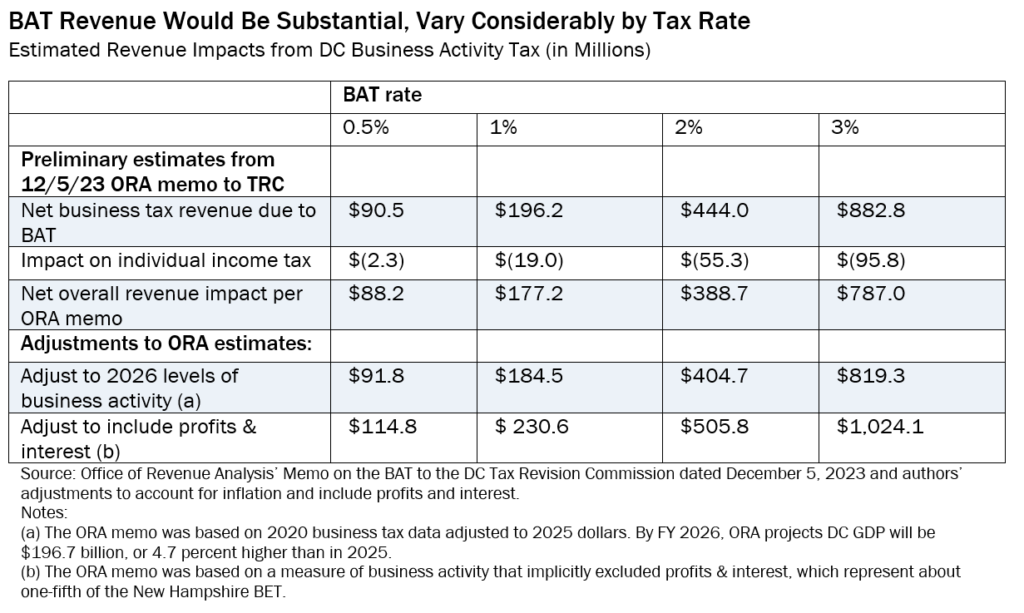

Even at low rates of taxation, a BAT would raise significant revenues. The Office of Revenue Analysis (ORA) prepared preliminary revenue estimates for the Tax Revision Commission in 2023 that indicated that a 0.5 percent BAT, as described in this report, would raise at least $177 million annually, a 2.0 percent BAT could raise at least $389 million, and a 3.0 percent BAT could raise $787 million in FY 2025 dollars. These estimates are net of the tax credits that would be available to businesses who pay the BAT.

For several reasons, it is likely that these estimates are on the conservative side. For one thing, they are based on 2020 business tax data, unadjusted for inflation and economic growth that has occurred since then. Moreover, for reasons of data availability, ORA based its estimates on only the portion of business activity that is documented through a business’s payroll and other compensation. In effect, the ORA estimate likely understates the real level of revenue that would be produced because it does not account for profits and interest.

Table 4 shows ORA’s preliminary revenue estimates calculated in 2023, which were based on 2020 data focusing on payroll and compensation. The table suggests adjustments to account for six years of inflation and economic growth and to reflect that the actual tax base, including profits and interest, is likely to be about one-quarter greater than the tax based used in the ORA estimates.

But even with those adjustments, as with any new tax, the exact scale of a BAT’s revenue production is uncertain. So, the District will need to budget this new revenue with great caution, at least initially. To address this revenue uncertainty, the District could begin with a zero-percent tax in the initial year, requiring taxpayers to complete the calculations but not actually pay the tax until better revenue estimates can be made.

Revenue Could Potentially Reduce or Replace the Tax Increases Enacted in the FY 2025 Budget

The District could use a portion of the revenue from a BAT to replace or reduce some of the revenue increases enacted in the FY 2025 budget. Two major tax increases may be worth reconsidering or scaling back.

One is the immediate increase in the Universal Paid Leave tax from 0.26 percent to 0.75 percent of payroll, paid by all non-government employers. The 0.26 percent tax was slightly more than enough to cover the projected costs associated with the Paid Family Leave program in FY 2025; the $322 million in annual new revenue from the tax increase will go into the general fund, transforming the tax from a social insurance fee to a general business and nonprofits tax with 80 percent of that coming from for-profit businesses.[18] This newly transformed tax resembles the BAT in some ways. It is broad-based, and its initial incidence is on employers (including partnerships and nonprofits who don’t pay the franchise tax). But the payroll tax is not as well structured as the BAT. It lacks the BAT’s $200,000 exemption, it’s not creditable against franchise tax, and it is more specifically tied to the DC-based workforce rather than business activity.

Reducing the payroll tax for businesses at the same time as a BAT is implemented would mean that some businesses would actually get a tax cut from the legislation. Consider the corporation profiled in Table 1. Not only would that business be unaffected, on net, by the BAT but if it has DC workers, then it has payroll tax liability—and that liability would decline.

Another potential tax change to finance with a BAT is to scale back the scheduled increase in the general sales tax from 6 percent to 6.5 percent effective October 1, 2025, and to 7 percent effective October 1, 2026. This increase is expected to generate $112 million annually for the general fund when fully implemented in 2027.[19] A disproportionate share of this tax would be paid by middle- and low-income households; the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy estimates that sales taxes cost middle- and low-income families more than ten times as much, relative to their incomes, as they cost high-income households.[20] DC’s brick-and-mortar retailers also could be affected, as consumers could save a bit of money by shopping in Maryland or Virginia.

DC Leaders Could Consider Maintaining a Higher Payroll Tax for Nonprofits to Ensure They Contribute to the District’s Shared Resources

Were the District to use the BAT to scale back the payroll tax, it may wish to consider doing so only for for-profit employers who will be subject to the BAT. Nonprofit organizations—not subject to the BAT—are a different story. Like for-profit businesses, nonprofit organizations rely on the services provided by the District, as do their employees (whether DC residents or not). They enjoy a wide array of tax breaks that are not contingent on the benefits they provide to DC residents.

These exemptions have a big impact, because DC nonprofits each year represent roughly 20 percent of the DC economy. Nonprofits including universities, hospitals, professional associations, and others annually save roughly $260 million from real property tax exemptions and $184 million in sales and personal property tax exemptions, according to the DC Tax Expenditure Report. Many of these exemptions were enacted prior to Home Rule, when the federal government—not DC residents—determined who should or shouldn’t pay DC taxes.

There is a reasonable policy argument that nonprofits, like for-profit entities, should pay tax that reflects the privilege of operating in the District. Many of DC’s nonprofits are national in focus, meaning that DC residents are effectively subsidizing charitable activity that overwhelmingly benefits the rest of the country. And while nonprofits, by definition, do not earn a profit, there are a few that are clearly quite prosperous, with very large money-making endowments, highly compensated employees, and a well-off clientele. Since they won’t be paying for the BAT, they should continue to pay the payroll tax.

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), nonprofit organizations account for about 20 percent of DC private-sector wages, so leaving the 0.75 percent payroll tax in place for those organizations might be expected to preserve roughly $65 million of the $322 million in tax revenue generated by the payroll tax increase. Alternatively, reducing the rate to 0.62 percent where it was initially set at the start of the paid leave program would preserve roughly $54 million of the increase on nonprofits.

Source for nonprofit wage data: BLS, “2022 Annual Averages; Private Nonprofit Establishment Data at 2-digit, 3-digit, and 4-digit NAICS Industry,” August 2024.

BAT Revenue Can Replace Lost Revenue and Sustain Services

The District projects that in coming years, total revenue including the newly enacted tax increases, will fail to keep pace with economic growth. One reason is that downtown commercial real estate, although still a major source of property tax revenue for the District, appears to be declining in value, so the landlords and tenants in those buildings are likely to pay less tax.

In 2015, the real estate taxes paid by the owners of the 572 most valuable buildings—those valued at over $10 million in 2020—represented over 15 percent of DC total tax revenues; by 2023, those same buildings’ property taxes provided less than 11 percent of taxes, equivalent to a loss of $440 million. If property values, and hence assessments, continue to decline, the loss will be still greater.[21] Other revenue sources, like the personal property tax on business equipment, are also declining. The net result is that local revenues in FY 2028 are projected to be lower, relative to personal income, than they were in FY 2024—even with a higher sales tax and payroll tax in place.[22]

Meanwhile, federal aid is declining as pandemic-era fiscal relief ends; this could be exacerbated if the Trump administration succeeds in enacting deep spending cuts. And the need and demand for public services in the District is unlikely to decrease. Furthermore, a BAT could help to expand much-needed investments. For example, this tax paid by a broader set of businesses could help to fully fund the Birth-to-Three law that would make child care affordable to all families in DC, which would in turn be a boon to DC’s businesses and economy.[23]

Declining tax revenues are not keeping pace with the District’s growing economy, which threatens to undermine the strong foundation of public services that the District has established over the last two decades. For locally raised revenues in the coming four years to be consistent with the average level of revenues over the last 23 years as a share of the economy—the District would need an additional $1.8 billion in annual revenue by 2028. [24] BAT revenue would help fill that gap.

Appendix 1: Additional Examples of How the BAT Would Affect Entity-Level Business Taxes

- DC is not allowed to tax any income earned by non-residents. For more discussion, see: Erica Williams and Nikki Metzgar, “The Hight Cost of Denying Statehood to the District of Columbia,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, January 19, 2023.

- Statutory authority for these taxes is in the Code of the District of Columbia, Title 47, Chapter 18, Subchapters VII and VIII. Tax forms and booklets for the corporate franchise tax (D-20) and unincorporated franchise tax (D-30) may be found on the Office of Tax and Revenue website.

- Government of the District of Columbia, “FY 2025 Approved Budget and Financial Plan: Volume 1 Executive Summary,” July 30, 2024, Table 4A-1.

- Section 602(5), District Of Columbia Home Rule Act, Public Law 93-198, approved December 24, 1973.

- Bishop v. District of Columbia, 401 A.2d 955 (1979) and 411 A.2d 997 (1980). See also Charles Butler, Bishop v. District of Columbia: Taxation of Unincorporated Professionals’ Net Income Violates Home Rule, Catholic University Law Review, Summer 1980.

- Create Business Activity Tax (BAT), unpublished memo from Office of Revenue Analysis to DC Tax Revision Commission, undated.

- The franchise tax rate is a flat 8.25 percent and a large share of individual income taxpayers are in the 8.5 percent bracket (income range from $60,000 to $250,000), so for many there is a rough equivalence between the franchise tax and the income tax, but high- and low-income taxpayers may be better off under one tax or the other.

- Matthew Gardner, Steve Wamhoff, and Spandan Marasini, “Corporate Tax Avoidance in the First Five Years of the Trump Tax Law,” February 2024.

- Office of Revenue Analysis, “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” September 2024.

- Lawmakers originally adopted this tax to pay for paid leave for DC workers and, unlike federal payroll taxes, only employers pay the tax.

- For example, see Alan D. Viard, “Addressing the Long-Term Fiscal Imbalance with a Value-Added Tax,” Statement before the House Committee on Ways and Means Subcommittee on Tax, American Enterprise Institute, December 2023.

- Angela DeFranco, “Memo to Anthony Williams, Chairman, DC Tax Revision Commission,” DC Chamber of Commerce, June 27, 2024, page 1.

- Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development’s home page, available at https://dmped.dc.gov/page/sectors, accessed January 10, 2025.

- Council Office of Racial Equity, “DC Racial Equity Profile for Economic Outcomes,” January 2021.

- National Association for Law Placement, Report on Diversity in U.S. Law Firms, January 2024, Table 12.

- US Bureau of Economic Analysis, “SAGDP2N Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by State,” accessed Sunday, January 12, 2025.

- DC Tax Revision Commission, “New Hampshire Briefings: Understanding the New Hampshire Business Enterprise Tax,” May 2024.

- Office of the Chief Financial Officer, “Revised Fiscal Impact Statement – “Fiscal Year 2025 Budget Support Act of 2024,” June 25, 2024 page 39

- Office of the Chief Financial Officer, “Revised Fiscal Impact Statement – “Fiscal Year 2025 Budget Support Act of 2024,” page 83.

- Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “District of Columbia: Who Pays? 7th Edition,” December 2022.

- Daniel Muhammad, “The Increasing Levels of Vacant Office Space: The Achilles’ Heel of DC’s Office Market,” Office of Revenue Analysis, July 2024.

- In 2024, local fund revenues equaled 14.0 percent of DC personal income; by 2028, that will decline to 13.1 percent. Source: DCFPI calculations from the DC Chief Financial Officer September 2024 Revenue Estimates.

- Anne Gunderson, “Expanding Child Care Subsidies Would Boost the District’s Economy,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, July 17, 2024.

- Updated, unpublished analysis of quarterly personal income data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and projections for Local Fund revenue and economic data from “December 2024 Revenue Estimates for FY 2025 – FY 2028,” based on methodology in Erica Williams, “DC Must Grow Revenue and Spending to Pursue More Transformative Change,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute May 2024.