This report was supported by the research of Allan Freyer, Ph.D., of Peregrine Strategies.

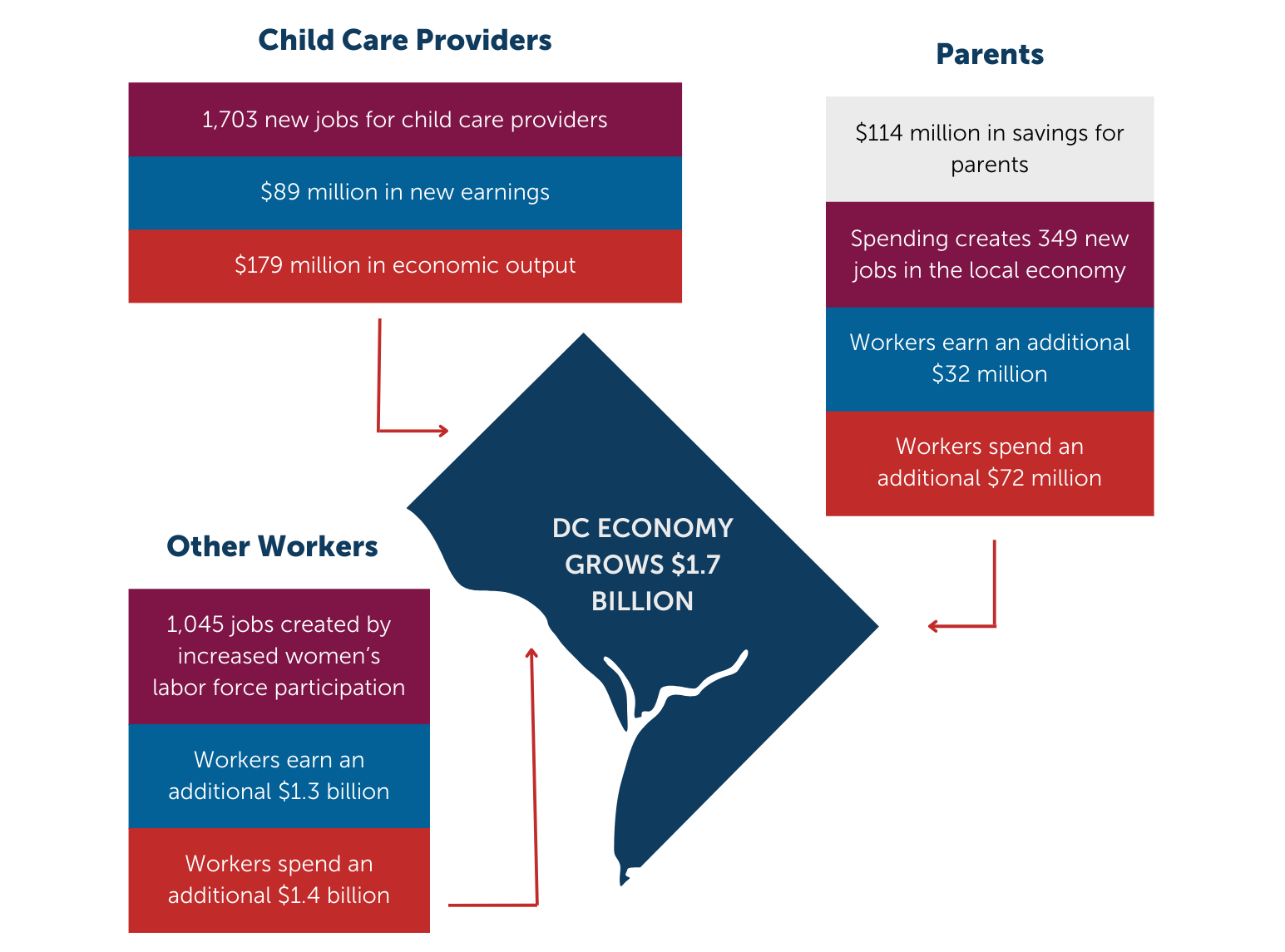

DC can grow its economy through expansion of affordable child care to all families. With additional investment in its child care subsidy program, DC can offset the high cost of child care and enable parents to go to work or school while their children engage in positive early learning experiences. Helping families pay for child care, regardless of income level, would significantly boost DC’s economy by removing barriers to women’s participation in the workforce, freeing up family budgets to purchase more necessities from District businesses, and increasing the money child care providers have to overcome tight margins, hire more staff, and improve their facilities.

DC recently expanded access to the subsidy program to more families, recognizing that investing in affordable, high-quality care can facilitate economic gains for Black and brown families, small and large businesses, and the DC economy as a whole. Increasing public funding for the DC child care subsidy program is also necessary to overcome centuries of underinvestment due to structural racism and sexism that causes child care providers to operate with less than they need and charge parents more than they can afford.[1] Currently, District residents who do not participate in the subsidy program spend, on average, 26 percent of their annual income on child care costs for one child. For the District’s lowest income residents, who due to systemic racism are disproportionately Black and brown, child care can cost up to 32 percent of their annual pay.[2]

Given that primary child rearing duties continue to predominantly fall on women, researchers have long found that the lack of affordable child care services outside the home holds back women from entering the labor force and keeping a steady job at family-sustaining wages.[3] In DC, the lack of child care for the youngest children (ages 0-3) costs families of these children an estimated $252 million per year in lost wages (or, on average, $8,100 per family with children ages 0-3). The same study finds that employers and DC’s budget also lose out; In DC, inadequate child care for the youngest children costs employers $79 million, in aggregate, in lost productivity and turnover. It also means an aggregate annual loss of $64 million in tax revenue.[4]

Programs that make it easier for District families to afford and access child care, including increased subsidies for child care services, play a key role in supporting women entering the workforce, supporting providers, and boosting workers’ paychecks—all of which would have significant and positive impacts on DC’s economy. In fact, the DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI) estimates the cost of increasing access to child care subsidies to all families is $139 million, annually. This would:

- Bring 12,572 additional children into DC’s subsidy program,

- Create 3,097 new jobs across the District,

- Add $1.4 billion to all DC workers’ paychecks, and

- Result in $1.7 billion in economic growth in the first year alone.

The existing child care subsidy program in the District is not perfect—there are barriers eligible parents face to receiving child care subsidies and barriers child care providers face to accepting subsidies in their programs. The findings in this report make it clear that there is an economic imperative to address these issues so that the District can reap the benefits of new jobs and economic growth that come with expanded access to affordable child care.

Affordable Child Care Allows Parents to Work and the Economy to Thrive

Child care subsidies play a critical role in improving the overall economy of the District and financial outcomes for DC residents by addressing a key barrier many parents face in fully participating in the labor market. In the absence of affordable child care, parents must choose between caring for their children at home and going to work to support their families—what Vice President Kamala Harris has called an impossible choice and a national emergency.[5] This “impossible choice” is not just a crisis for families–it presents a problem for workers, employers, and the economy as a whole.

Caregiving Responsibilities Disproportionately Keep Women from Work and Full Participation in the Economy

When child care is out of reach, the choice between caring for children at home and working often falls on women, who are more likely to be primary caregivers. This forces them to give up their jobs or significantly reduce their hours. Women take more time out of the workforce to care for their children and are twice as likely as men to work part-time, recent studies suggest.[6],[7] This occurred during the pandemic, when a quarter of US women quit their jobs due to the lack of child care.[8]

When women return to work after taking time away to care for their children, they can face additional disadvantages in wages and career opportunities. Sometimes called the “motherhood penalty,” women with children are often paid less, receive fewer benefits, and face employers less willing to hire them than similarly educated and experienced women who don’t have children.[9] One study found women earn 5 percent less for every child they have.[10] Given this penalty and the myriad of overlapping discriminatory employment practices, the National Women’s Law Center estimates that women in DC earn just 84 cents for every dollar earned by men.[11] Moreover, spending less time in the workforce ultimately reduces their ability to financially support their families and can lower their Social Security retirement benefits which are based on work and earnings history.[12]

Helping Families Afford Child Care Would Increase Labor Force Participation and Employment

Increasing child care subsidies benefits the economy in several important ways. First, greater subsidy funding increases the ability of parents—especially women—to afford and use paid child care services. Families take advantage of child care services when they are available and affordable. For example, a 10 percent increase in the federal Child and Dependent Care tax credit has been found to increase participation in child care services by as much as 5 percent among households nationwide with children 13 and younger.[13]

Child care subsidies also increase women’s labor force participation and employment by removing child care-related barriers to entering and fully participating in the workforce. In effect, child care subsidies open the door for women to enter the labor force, find a job, and remain employed over the long haul. For example, the US Department of Health and Human Services recently found that for every 10 percent increase in child care subsidies, women’s labor force participation rose by 0.47 percent.[14] And these women are more likely to stay employed when they have adequate child care. According to the US Census Bureau, 98 percent of married mothers receiving child care subsidies in a given year remained in the labor force four years later.[15]

Subsidies increase women’s labor force participation, employment, and hours worked for pay, which is why boosting subsidies translates into significant additional economic growth. For every 10 percent increase in women’s workforce participation, wages for both men and women rise 5 percent across the nation’s metro areas, a recent Harvard Business Review analysis suggests.[16] Ensuring that women are able to participate in the DC labor force at a similar rate to men would also create a significant boost to the District’s gross domestic product (GDP). For example, the Brookings Institute estimates that the United States’ GDP could be 5 percent higher if women participated in the workforce at the same rate as men.[17]

Increasing child care subsidies especially benefits Black and brown women living in DC. These women are more likely than white women to play both the role of primary caregiver and be responsible for the financial security of the family, largely because a disproportionate share of Black and Latina mothers are single parents due to systemic factors.[18],[19] At the same time, occupational segregation has pushed Black and brown women into jobs, particularly in retail and health service occupations, that are less likely to provide paid family leave or other caregiving supports that make it easier to quickly return to the workforce after the birth of children and stay there.[20],[21]

In addition, Black and brown women are also more likely to live in “child care deserts,” or neighborhoods where affordable child care is absent.[22] Twenty-seven percent of Black DC residents and 31 percent of Hispanic residents live in a DC child care desert, which are mostly concentrated in Wards 4, 5, 7, and 8, according to a recent analysis by the Center for American Progress.[23] This underscores the importance of growing the supply of affordable, high-quality child care in these communities by addressing the barriers child care owners face to offer subsidy-eligible seats in their facilities.

State expansions of early childhood care and education have a track record of expanding the workforce, including in DC. For example, a previous study of DC’s universal pre-K program showed District families participated at an extremely high rate—more than 70 percent of eligible 3-year-olds and 90 percent of eligible 4-year olds participated in the program.[24] The program led maternal labor force participation overall to increase by 10 percentage points from 2008 to 2016 and by more than 15 percent for families living in poverty.[25] In addition, the share of DC’s mothers with young children (ages 5 and younger) who were employed rose from 56 percent to 67 percent over the same period.[26] The success of universal pre-K in DC suggests that expanding access to child care subsidies for our youngest children could also have positive employment outcomes for mothers.

Affordable Child Care Would Increase Productivity, Decrease Hiring Costs for Employers, and Boost Revenue

Expanding access to quality affordable child care through greater subsidization would not only help women and families, but also have positive ripple effects for businesses and DC revenue. Under 3 DC recently estimated that having no child care, or insufficient child care, can cost individual families with children ages 0-3 up to $8,100 per year, including through lost wages from fewer hours worked, being fired, or voluntarily withdrawing from the labor market to take care of children. In aggregate, these families lose $252 million in wages each year—money that could be recouped with increased access to child care subsidies.

Businesses lose, in aggregate, $79 million annually because of employee turnover, lost productivity, lost business revenue, and hiring costs due to lack child care. Taken together, Under 3 DC estimated the lack of adequate affordable child care for infants and toddlers costs DC much-needed revenue—an estimated $64 million per year.[27] That means businesses and DC residents more broadly have much to gain from expanded access to affordable child care.

Expanding Child Care Subsidies Would Grow the District’s Economy by $1.7 Billion in the First Year

Expanding child care subsidies to all eligible children in DC, regardless of income, would have a significant and positive benefit on the District’s economy, including more jobs, higher wages, and more overall economic growth.

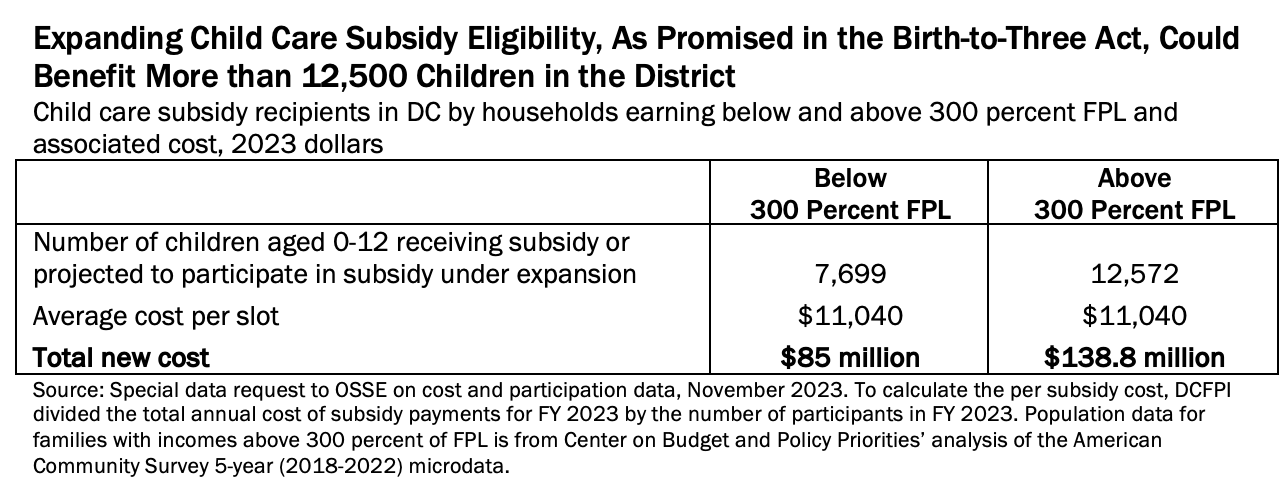

An estimated 12,572 District children whose families earn more than three times the federal poverty level (FPL)—the current income eligibility cap for entry into the subsidy program—would newly receive subsidies in the first year, almost doubling the number of total participants and increasing the annual program cost by $139 million (Table 1). This estimate is based on current participation rates by age group, which are far lower for preschool-aged children, for example, because of the availability of universal pre-K in the District, and due to access issues. (For the complete methodology, see Appendix I.)

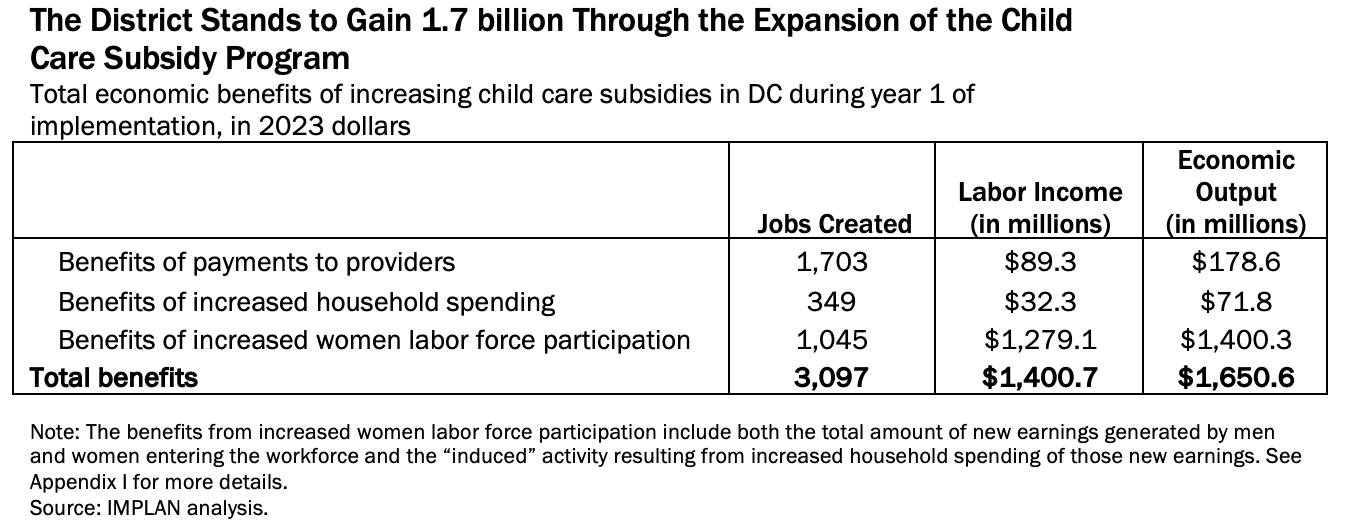

Once reaching DC families and providers, these additional subsidy dollars would generate significant new economic activity in the District. DCFPI measured this activity using IMPLAN, economic impact analysis software that analyzes the ripple effects of economic changes across multiple rounds of purchasing by businesses, their suppliers, and households (Appendix I). Assuming the supply is available to absorb the growth, these new subsidies would yield positive economic gains for DC residents in the first year, including:

- New jobs created in the child care sector due to increasing demand for child care and higher payments to providers,

- Freed up household spending that used to be poured into child care that could now be spent elsewhere, and

- Increased earnings among women who could now enter the workforce because they can afford child care (Table 2).

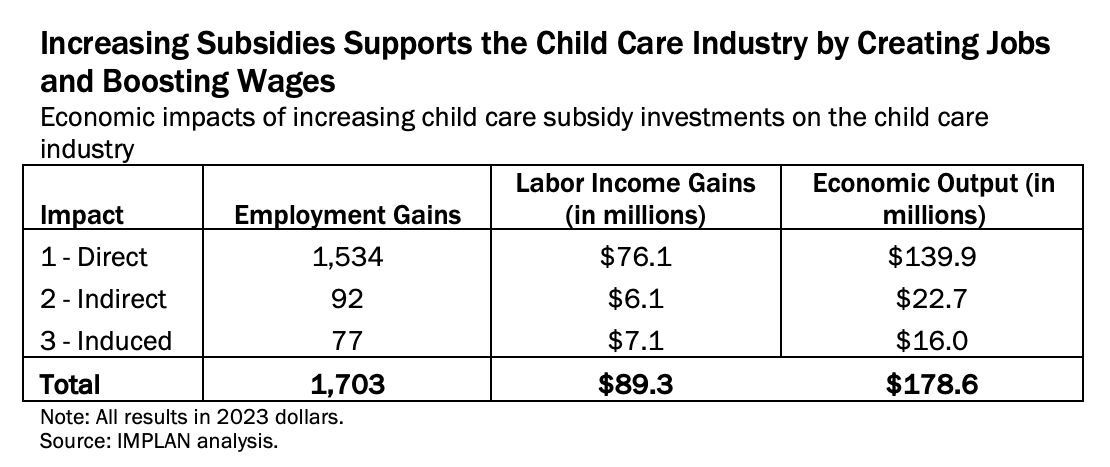

More Funding Going to Child Care Providers Means More Spending on Supplies and More Child Care Jobs

Subsidies also give an important boost to child care providers. Ripple effects from new payments to child care providers would generate 1,703 more jobs, $89.3 million in new labor income earned by District residents, and nearly $179 million in new economic output (GDP) (Table 2). These benefits are the result of $139 million in new child care subsidies flowing directly to providers in the form of reimbursements, based on the number of slots filled by the estimated 12,572 additional children entering the program for the first time because they are newly eligible. In turn, these child care providers spend this new money paying for staff and purchasing materials from suppliers—that is, dollars that end up generating new economic activity for businesses and families as they ripple across the District economy.

When Families Spend Less on Child Care, They Can Spend More on Everything Else

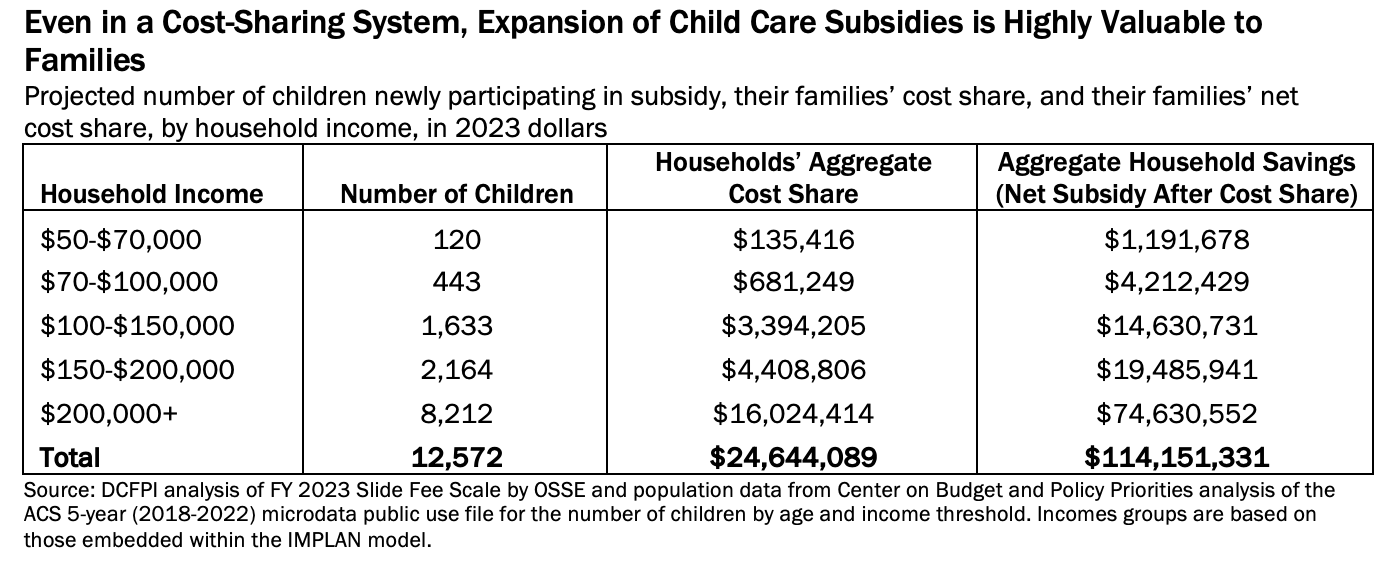

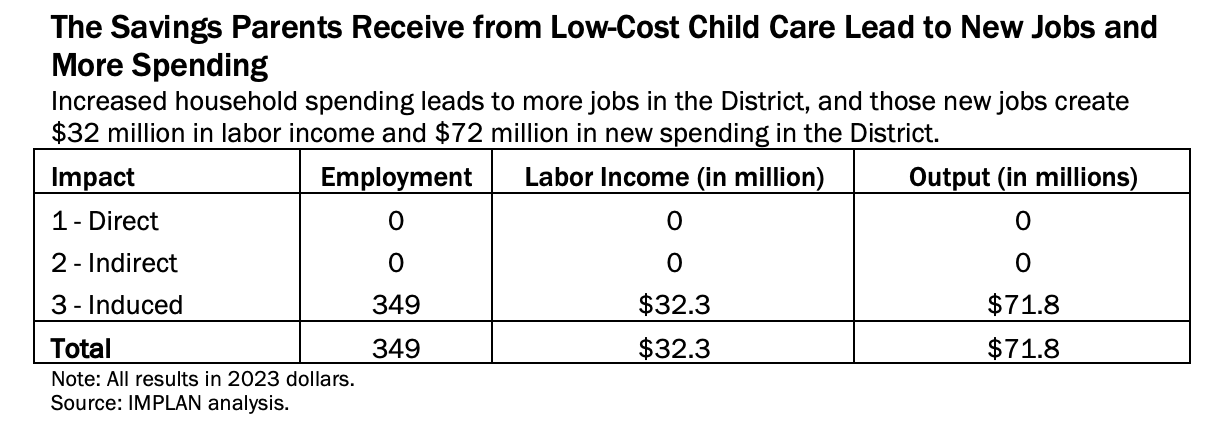

New child care subsidies mean families would have more money to spend. Access to child care subsidies would free up an additional $114 million in household budgets, allowing families to spend their income on other needs like groceries, housing, transportation, and purchasing other goods and services from DC businesses. This new spending would ripple across the DC economy and generate 349 new jobs, $32.3 million in new wages, and almost $72 million in new economic output.

Families across the income spectrum would benefit from increasing eligibility to households earning more than three times the FPL, but especially those with annual incomes above $100,000 (Table 3). To keep program costs down and ensure more equitable results, DC requires families to supplement the subsidy dollars their children receive by contributing to the overall costs charged by providers. The amount of this cost-share depends on family income, rising from $12.86 per day for full-time care paid by families earning between $50,000 and $70,000 every year to $26.82 per day for those families earning more than $100,000 per year in fiscal year (FY) 2023.[28] Added together across all income ranges, District families newly participating in the program would end up paying about $25 million out of their pockets for the cost-share and benefit from $114 million in net subsidies.

Affordable Child Care Allows Women to Work, Which is Good for Everybody

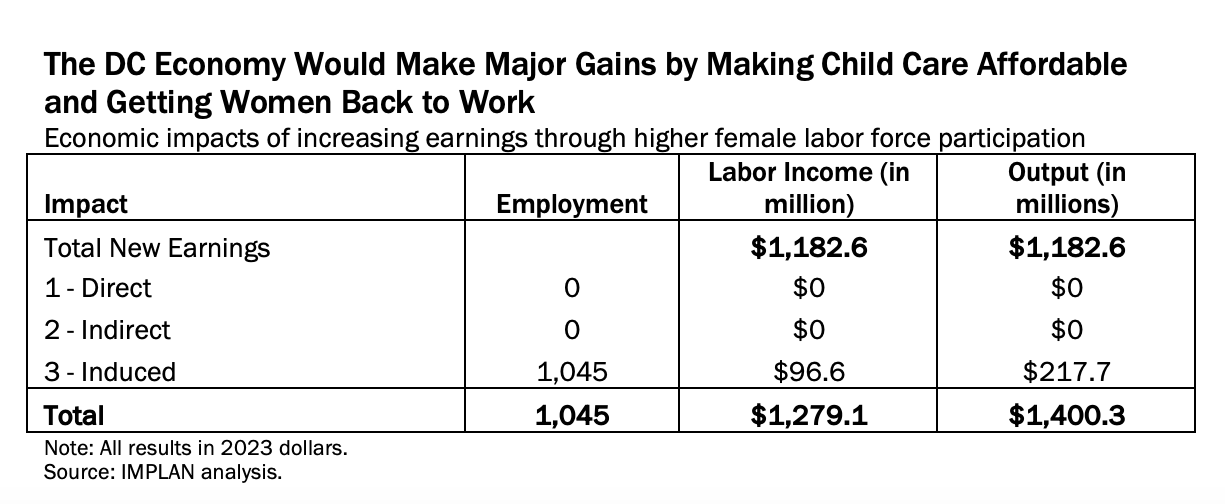

Child care subsidies grow women’s participation in the labor force and increase wages. Expanding eligibility for DC child care subsidies would significantly reduce child care-related barriers to work and bring an estimated 14,429 new women into the District’s labor force, increasing women’s labor force participation rate by 7.7 percent—a game-changing improvement to the local economy.

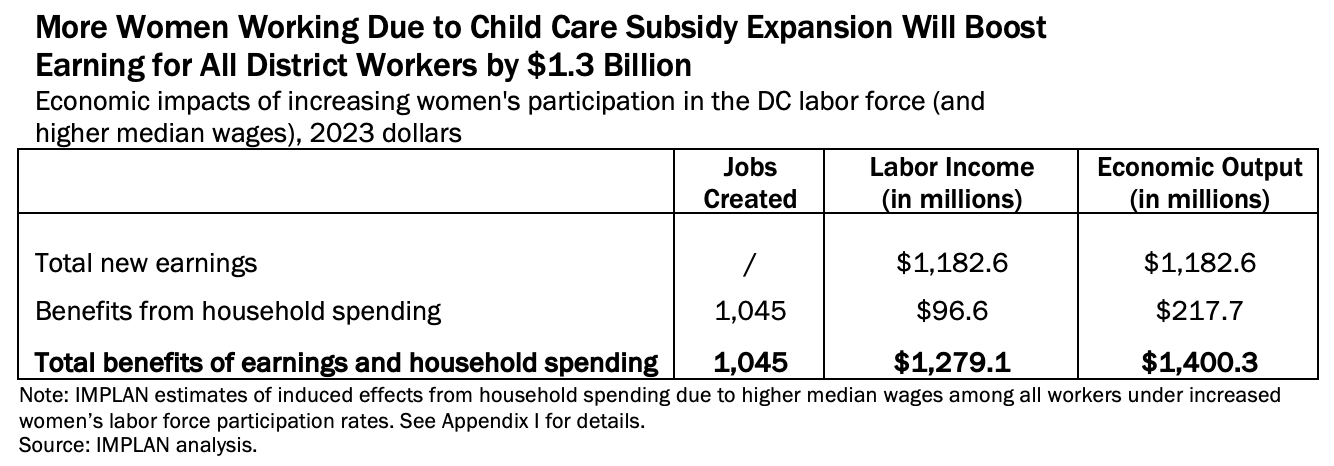

Based on previous research on the overall wage effects of increased female labor force participation (Appendix I), this increase for women in DC would translate into median paychecks rising by $2,857 annually for all 413,989 DC workers—a total of nearly $1.2 billion in new earnings flowing from workers’ pockets into the District economy. New household spending due to higher median paychecks would create 1,045 new jobs, almost $97 million in new labor income, and $217.7 million in new economic output. When added together, these labor force increases would yield a total of nearly $1.3 billion in new labor income and $1.4 billion in new economic output (Table 4).

Taking together the effects on child care providers, household spending, and increased women’s labor force participation, an increase in child care subsidies by $139 million would create a total of 3,097 jobs, boost earnings for District workers by $1.4 billion, and grow the overall size of the DC economy by $1.65 billion (Table 2).

Before Further Expanding the Child Care Subsidy Program, the District Needs to Improve Program Implementation and Access to Currently Eligible Families

DC’s child care subsidy program helps approximately 7,700 families with low and moderate incomes pay for the cost of child care.[29] The subsidy program is an avenue for predominately Black and brown parents—who have faced centuries of systemic oppression—to give their children a jumpstart on their education and to have a safe and supportive environment to place their children while they work or pursue an education.

In 2018, lawmakers passed the Birth-to-Three for All DC Act (Birth-to-Three), which set the vision for early care and education in the District and established a timeline for expanding child care subsidy to increasingly higher income families until all District families would be eligible in 2027.[30] DC lawmakers recently expanded eligibility for the program to families making up to 300 percent of the FPL, benefitting an estimated 2,200 additional children.[31]

Lawmakers were able to afford the expansion because fewer parents tapped into the program than what the District expected. The underutilization of child care subsidy stems from declining birth rates (i.e., lower demand) and an increasing mismatch between supply and demand for certain age groups and parts of the District.[32],[33] Before further expanding eligibility for the child care subsidy program to higher income families, the District should implement additional policy and practice improvements that solve current underutilization. Some of the causes of underutilization include:

- Demand-side issues such as difficulties accessing and completing an application for the subsidy, fulfilling eligibility requirements related to working or pursuing education, delays in the approval process, and a geographic mismatch between child care needs and availability. Many parents seek care for their children outside of traditional operating hours, bilingual services, or care for special needs. Finding a child care center or home that accepts subsidy and offers specialized services is especially challenging.[34]

- Supply-side issues such as long waits and significant paperwork required by providers to accept subsidy-eligible children, reimbursement rates that fall below the cost of providing high-quality care, and child care workforce shortages.[35]

The DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) and the Department of Human Services (DHS), which jointly administer the child care subsidy program, have taken steps to resolve some of these barriers within the last year. They have improved communication with District families to ensure that they know about the subsidy program and how to access it, created an online application process, and continue to work to streamline the approval process to reduce wait times from when a parent applies for subsidy and when they receive it.[36] OSSE and DHS should continue to monitor the effectiveness of these changes and implement further improvements to the application and approval process, especially as the District expands eligibility to higher income families. However, the forthcoming $10 million cut to the subsidy program in the FY 2025 budget may limit OSSE’s ability to invest in implementation improvements, threatening this progress.

Once a family has a child care voucher in hand, they must find a child care facility that accepts subsidy and meets their needs. At this point in the process, supply-side issues set in. A family’s preferred provider may not have an open seat for their child’s age group, offer evening hours when they need care, or participate in the subsidy program. Over the past five years, the District has experienced a decline in both the supply of and demand for child care, but gaps remain, particularly for “quality child care, for economically disadvantaged families, and for children who need specialized services such as nontraditional hours and bilingual settings,” according to a study by the Bainum Family Foundation.[37] Demand for subsidized infant and toddler seats is outpacing the supply by more than 3,000 seats.[38] That gap grows for families seeking care during nontraditional hours, bilingual services, and care for children with special needs. These supply-side issues require deeper research and better data to understand why utilization is declining while demand remains high, and the full scope of the barriers facing providers who want to offer subsidy seats.[39]

Expanding eligibility for DC’s child care subsidy would have major economic benefits for all District residents, as outlined in this report, but only if there is sufficient supply to meet the diverse needs of the children and families this program serves. Therefore, it is an economic imperative to address these issues so that the District can reap the benefits of new jobs and economic growth that come with expanded access to affordable child care.

There is an Economic Imperative to Increase Access to Affordable Child Care

The lack of affordable quality child care in the District is a crisis. Addressing this crisis with expanded access to child care subsidies would be a massive boon not just for families and children, but for the entire District economy. DC policymakers should address existing supply and demand issues and then increase child care subsidies to include those 12,572 children whose families earn more than three times the FPL and who DCFPI estimates would take up subsidy based on current enrollment rates. Taking these steps would support providers, free up family budgets, and bring thousands of women newly into the District’s labor force, all of which would create thousands of jobs, raise wages, and grow the economy by $1.7 billion dollars.

Appendix I: Methods

DCFPI commissioned Allan Freyer, the Principal of Peregrine Strategies, to conduct the economic analysis underpinning this report. Freyer used IMPLAN, the proprietary economic impact analysis software package, to estimate the various economic impacts of increasing child care subsidies to children whose families earn above 300 percent of the federal poverty level.

Study Area and Study Period

DCFPI conducted this study within DC. All results are reported for a single year, the first year child care subsidy expansions would go into effect.

Using IMPLAN to Estimate the Economic Impacts of New Child Care Subsidies

IMPLAN is an input-output modeling program that permits researchers to estimate the projected effects of an exogenous change in demand—such as an increase in child care subsidy dollars—in a specified geographic region, such as DC. The software analyzes the ripple effects of new spending across the study area, first by assessing the Direct Effects (the impacts of increased purchasing among an industry’s suppliers), Indirect Effects (the impacts of those suppliers spending more money), and Induced Effects (the impacts of households spending the additional income they earn thanks to the economic activity generated by the Direct and Indirect rounds of spending).

The software is typically used by economic developers looking to assess the impacts of new locations or tax changes. But it has also been used to model the impacts of minimum wage changes in other states and increased labor income resulting from greater female labor force participation in Alabama, and as a result, it is well suited to assessing a range of impacts resulting from increased child care subsidies, including those related to increased labor income and family spending.[40],[41]

Specifically, DCFPI used IMPLAN to estimate the impacts of increasing child care subsidies on the District economy in three different ways:

- Increased direct payments to providers.

- Increased household income freed up by the subsidies and spent on other goods and services.

- Increased earnings for all District workers resulting from increased female labor force participation.

DCFPI reports results from these IMPLAN analyses in three different categories—employment (the number of jobs created), labor income (the amount of new income earned by workers), and economic output (GDP).

Data Sources

In conducting this analysis, DCFPI relied on several different sources of data, including DC Child Care Subsidy Program data for FY 2023, US Bureau of Labor Statistics labor force participation data (2022), the American Community Survey’s (ACS) 1-year 2023 earnings estimates for DC working age residents, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of the ACS five-year (2018-2022) microdata public use file for the number of children by age and income threshold, and IMPLAN’s proprietary 2022 dataset.

Estimating the Number of New Children and How Much it Would Cost

To determine how much money would flow to providers and households, DCFPI first estimated the number of children whose families earn above 300 percent FPL who would participate in an expanded program. This involved a three-step process.

First, DCFPI used the ACS microdata to determine how many District children live in families above and below 300 percent FPL by age and income threshold, on average, during the 2018-2022 period. Due to small sample sizes, DCFPI inputted the number of children above 300 percent FPL aged 0-2, 3-5, and 6-12 for households earning based on their percentage of all District children. Using this method, DCFPI found that there were 55,214 DC families earning more than 300 percent FPL, on average, during the 2018-2022 period.

Second, DCFPI estimated the subsidy participation rate by income threshold for children living above 300 percent FPL. DCFPI started this step by calculating the percentage of children below 300 percent FPL actually receiving subsidies (e.g., the participation rate) for each age group (0-2, 3-5, and 6-12) using the subsidy data provided by the District.[42] In the absence of other evidence, DCFPI then assumed that children in each age group above 300 percent FPL would participate at the same rate as their counterparts below 300 percent FPL, regardless of income threshold. Based on this assumption, DCFPI next calculated the percentage of children above 300 percent FPL in each age group who would participate in the program and receive subsidies and then multiplied those percentages by the number of children in each age group within each income threshold. Participation rates vary by age group in large part due to the availability of universal pre-K in the District, which significantly reduces the number of 3-to-5-year-olds who would otherwise need a child care subsidy. Finally, DCFPI then summed together the number of participating children in each age group by their respective income thresholds, giving the total number of children above 300 percent FPL who DCFPI estimates would participate in the program and receive subsidies. Using this method, DCFPI estimated that 12,572 children in families earning above 300 percent FPL would receive child care subsidies.

Third, DCFPI estimated the dollar amount needed in new appropriations to provide subsidies to these children. To start, DCFPI calculated the average subsidy amount per child for existing participants (those below 300 percent FPL) using FY 2023 program data, which came to a total of $11,040 per child.[43] DCFPI then assumed that this per-child cost would remain the same for children above 300 percent FPL and multiplied this amount by the 12,572 new children entering the program. This yielded a total subsidy cost (and total appropriation) of $138,795,420.

Estimating the Economic Impact for Child Care Providers

In the first economic impact model, DCFPI used IMPLAN to measure the ripple effects of increased subsidies to child care providers in particular—the additional dollars child care centers would spend on staff, supplies, facilities, and other goods and services thanks to the new subsidies. Specifically, DCFPI ran the model as an Industry Impact Analysis Event, assigning the $138,795,420 in new subsidies to the Child Day Care Services industry (code 494). IMPLAN reported the following results (Table A1):

Estimating the Economic Impact for Family Household Spending

In the second economic impact model, DCFPI used IMPLAN to estimate the impacts of the new subsidies on household spending, recognizing that once families are able to spend less on child care, they’ll have more to spend on other goods and services in the DC economy. As seen in Table A2, DCFPI divided up the total subsidy amount by the number of new children/participants in each income threshold.

We then calculated the amount of the cost-share required by the District for each participant. The amount of this cost-share depends on family income, rising from $12.86 per day for full-time care paid by families earning $50,000-$70,000 every year to $26.82 per day for those families earning more than $100,000 per year.[44] Added together across all income ranges, District families newly participating in the program would end up paying about $25 million out of their pockets for the cost-share and benefit from $114 million in net subsidies. The amounts reported in the of Table 3 represent the total amount of subsidy flowing to families in each income threshold once the cost share is taken into account.

DCFPI then used the Net Subsidy values as the inputs for IMPLAN to run a household income and spending analysis. The software analyzed how households in each income threshold would spend these additional dollars across the DC economy, which resulted in the following impacts (Table A2):

Estimating the Economic Impact of Increased Female Labor Force Participation

In the final model, DCFPI estimated the impact of increasing child care subsidies on female labor force participation, and the resulting impact on DC’s economy. Because the software does not have a direct way to convert labor force participation into economic impact, DCFPI used a multi-step process to develop the input for the IMPLAN model. This involved converting subsidy increases into female labor force participation increases into District-wide earnings increases, which DCFPI used as the IMPLAN input for a Labor Income Impact Analysis.

For the first step, DCFPI calculated the impact of increased child care subsidies on the female labor force participation rate, using a 2016 national study released by the US Department of Health and Human Services that found that every 10 percent increase in child care subsidies contributed to a 0.47 percent increase in the female labor force participation rate across the country.[45] DCFPI applied this same logic to DC and found that increasing child care subsidies by $139 million would represent a 163 percent increase over the $85 million spent in 2023 and translate into a 7.7 percent increase in the District’s Female Labor Force Participation rate. This would result in 14,429 women entering the workforce in the first year of expanded subsidies.

Second, DCFPI estimated the impact of increased female labor force participation on earnings by District workers. A recent Harvard Business Review study found that for every 10 percent increase in the female labor force participation rate, median earnings for both women and men rose by 5 percent across the nation’s metro areas, in response to more women earning a paycheck and men’s pay rising to remain competitive.[46] As with the previous step, DCFPI applied this logic to the District and calculated that the 7.7 percent increase in female labor force participation would boost individual workers’ median earnings by $2,857 per year. Multiplied across all 413,989 DC workers who had earnings in 2022, this resulted in a total of $1.2 billion in new learned across the District economy.

Third, DCFPI used IMPLAN to model the impact of these $1.2 billion in new earnings as a Labor Income event to reflect the ripple effects of workers spending bigger paychecks across the DC economy. It is important to note that for labor income changes like these, the software only reports “Induced Effects,” which capture tail-end economic ripple effects of shifts in household spending resulting from the total change in earnings modeled (e.g., resulting from the earnings gain from greater labor force participation). But the goal was to estimate the total impact on DC’s economy, which also includes the original amount of the new labor income that would flow to the District if female labor force participation increased. Therefore, DCFPI combined both the Induced Effects and the new earnings when reporting results (Table A3).

Although it is unusual to combine original and induced effects in this way for labor income changes in particular, staff economists at IMPLAN advised that this would be appropriate in this case, since the economic change is not associated with a separate Industry event (increasing child care subsidies), and that the model should reflect the full range of an economic change that includes both new earnings (caused by greater participation in the labor force) and the induced effects (the ripple effects of the input) together. DCFPI’s results include the following:

[1] Christine Johnson-Staub, Equity Starts Early, The Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP), December 2017.

[2] United Way NCA, The Childcare Cost Burden for Low-Income Households Around the U.S., October 14, 2023.

[3] Women’s Foundation of Alabama, Clearing the Path: Galvanizing the Economic Impact of Women, 2022.

[4] Sara Watson, Under 3 DC, The High Cost of Unaffordable Child Care, March 2024.

[5] Kamala Harris, The exodus of women from the workforce is a national emergency (Opinion), The Washington Post, February 12, 2021.

[6] The Women’s Fund of Greater Birmingham, Clearing the Path: Strengthening Child Care, Strengthening Alabama, 2021.

[7] Jessamyn Schaller, Ph.D., The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap, American Association of University Women, 2021; Ariane Hegewisch, Marc Bendick, Barbara Gault, Heidi Hartman, Pathways to Equity – Narrowing the Wage Gap by Improving Women’s Access to Good Middle-Skill Jobs, Institute for Women’s Policy Research, March 2016.

[8] Sandra Bishop, Ph.D., $122 Billion: The Growing, Annual Cost of the Infant-Toddler Child Care Crisis, Ready Nation, February 2023.

[9] Jessamyn Schaller, Ph.D., The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap, American Association of University Women, 2021.

[10] Tamar Kricheli-Katz, Choice, Discrimination, and the Motherhood Penalty, Law & Society Review, September 2012, 46(3), 557–587.

[11]National Women’s Law Center, The Wage Gap, State by State, March 2024.

[12] John A. Turner, Emily S. Andrews, David Rajnes, Why Are Women More Pessimistic About Social Security’s Future Than Men?, Social Security Administration, Office of Retirement and Disability Policy, August 2023.

[13] Gabrielle Pepin, The Effects of Child Care Subsidies on Paid Child Care Participation and Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from the Child and Dependent Care Credit, W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, August 4, 2020.

[14] Kimberly Burgess, Nina Chien, Maria Enchautegui, The Effects of Child Care Subsidies on Maternal Labor Force Participation in the Unites States, ASPE Office of Human Services Policy, December 20, 2016.

[15] Benjamin Gurrentz, Child Care Subsidies Help Married Moms Continue Working, Bring Greater Pay Equity, United States Census Bureau, October 12, 2021.

[16] Amanda Weinstein, When More Women Join the Workforce, Wages Rise — Including for Men, Harvard Business Review, January 31, 2018.

[17] Janet Yell, The history of women’s work and wages and how it has created success for us all, The Brookings Institution, May 2020.

[18] Milia Fischer, Women of Color and the Gender Wage Gap, Center for American Progress, April 14, 2015.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Jessica Washington, One Paycheck Away From Losing Everything’: Why The Child Care Crisis Is Especially Hard for Black Mothers, The Fuller Project, August 25, 2021.

[21] Milia Fischer, Women of Color and the Gender Wage Gap, Center for American Progress, April 14, 2015.

[22] Cristina Novoa, How Child Care Disruptions Hurt Parents of Color the Most, Center for American Progress, June 29, 2020.

[23] Rashid Malik, Katie Hamm, Leila Schochet, Cristina Novoa, Simon Workman, Steven Jessen-Howard, America’s Child Care Deserts in 2018, Center for American Progress, December 6, 2018.

[24] Rashid Malik, The Effects of Universal Preschool in Washington, D.C.: Children’s Learning and Mothers’ Earnings, September 26, 2018. Center for American Progress.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Sara Watson, Under 3 DC, The High Cost of Unaffordable Child Care, March 2024.

[28] DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Fiscal Year 2023 (FY23) Slide Fee Scale, 2023.

[29] Utilization data from the DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, FY 2023.

[30] DC Law 22-179: Birth-to-Three for All DC Amendment Act of 2018.

[31] DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Mayor Bowser Expands Access to Affordable High-Quality Child Care for DC Families, March 2023.

[32] Sara Mead, Assistant Superintendent of Early Learning, Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Conversation with Under 3 DC Policy Group, January 2024.

[33] In 2023, there were 40,295 children in the District in families with incomes below 300 percent FPL, but only 7,699 children were served by child care subsidy, based on population data from CBPP and utilization data from the DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE).

[34] Robyn Russell, Nkechi Enwerem, and Zillah Jackson Wesley, Child Care for Young Parents: A Missing Key to Intergenerational Upward Mobility in the District, Howard University, DC Next, and DC Primary Care Association, September 2023.

[35] Audrey Kasselman, DC Action, Letter to OSSE: Recommendations for CCDF State Plan, May 2024.

[36] DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, OSSE Announces Expanded and Improved Access to Child Care Subsidies for DC Families, November 2023.

[37] Bainum Family Foundation, Assessing Child Care Access: Measuring Supply, Demand, Quality, and Shortages in the District of Columbia, page 11, January 2024.

[38] Ibid.

[39] DCFPI has forthcoming research to better understand the barriers child care owners have to offering subsidy seats.

[40] Minimum wage IMPLAN reports

[41] Women’s Foundation of Alabama, Clearing the Path: Galvanizing the Economic Impact of Women, 2022.

[42] Data provided by the Data, Assessment, and Research division of the Office of the State Superintendent of Education, January 2024.

[43] Cost and participation data received from the Office of the State Superintendent of Education, November 2023. To calculate the per subsidy cost, DCFPI divided the total annual cost of subsidy payments for FY23 by the number of participants in FY23.

[44] DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Fiscal Year 2023 (FY23) Slide Fee Scale, 2023.

[45] Kimberly Burgess, Nina Chien, Maria Enchautegui, The Effects of Child Care Subsidies on Maternal Labor Force Participation in the Unites States, ASPE Office of Human Services Policy, December 20, 2016.

[46] Amanda Weinstein, When More Women Join the Workforce, Wages Rise — Including for Men, Harvard Business Review. January 31, 2018