Chairperson Mendelson, members of the committee, and committee staff, thank you for the opportunity to testify. My name is Erika Roberson, and I am a Policy Analyst at the DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI). DCFPI is a non-profit organization that shapes racially-just tax, budget, and policy decisions by centering Black and brown communities in our research and analysis, community partnerships, and advocacy efforts to advance an antiracist, equitable future.

Today, I would like to discuss DCFPI’s preliminary analysis of the fiscal year (FY) 2025 initial school budgets for DC Public Schools (DCPS). DCFPI is grateful to the mayor for increasing most public schools’ budgets and bolstering the amount of dollars for students “at-risk of academic failure.” Even with these increases, schools will face constrained budgets next school year due to higher labor costs, high inflation, and the loss of crucial federal pandemic funding—likely forcing some schools to lay off employees. Given the declines in enrollment and budgets in schools in Wards 5, 7, and 8—which serve a majority of Black and brown students and those with low incomes—DCFPI’s analysis focuses on these wards. Key findings include:

- Schools in Wards 5, 7, and 8 will lose buying power due to rising labor costs and the expiration of Elementary and Secondary Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds, despite nearly all schools seeing year-to-year increases in their budgets;

- Four schools in these Wards face cuts larger than 5 percent, which is a violation of DC law. And DCPS is failing to apply its budget model consistently across schools, undermining educational equity;

- DCPS is increasing “at-risk” funds for schools, but greater transparency is needed on how schools are using these funds to ensure they are reaching students furthest from opportunity; and,

- Schools in Wards 7 and 8 continue to face concerning enrollment declines, underscoring the need for DC policymakers to commit to investing in by-right neighborhood schools.

Schools Will Lose Buying Power in FY 2025, Despite Local Fund Increase in Budgets

Nearly all schools in Wards 5, 7, and 8 receive an increase in their FY 2025 initial budgets compared to FY 2024 amended budgets. On average, schools in these wards are seeing an annual budget increase of 14, 9, and 3 percent, when adjusted for inflation. However, these increases are not enough to keep up with growing labor costs for several schools, even some schools with enrollment gains. Due to successful Washington Teacher Union negotiations, more educators are benefitting from higher salaries, rewarding their hard work and helping them keep up as rent and prices of goods continue to rise.[1]

Next school year, the average salary for a teacher will increase by 16 percent to reach $133,722—a percentage that far outstrips the average budget increase that Ward 7 and 8 DCPS schools will get.[2] And the average salary for non-allocated positions, such as assistant principals, will increase by 17 percent. The initial school budgets do not show the total number of positions that a school will have, but it is likely that inadequate budgets will force some school leaders to lay off non-allocated positions.

When you compare FY 2025 initial school budgets to the FY 2024 amended school budgets and positions, only four schools in Ward 7 and one school in Ward 8 will see a budget increase of at least 16 percent, meaning they are better positioned to afford the growing labor costs.[3] This suggests that 88 percent of schools in Ward 7 and 8 have budgets that can’t keep up with increased labor costs alone.

Additionally, the expiration of $304 million in ESSER funds poses budget challenges for schools, especially those that used these dollars to pay for recurring positions because local funds were inadequate to meet students’ needs.[4] While the goal of ESSER dollars was always to temporarily address the acute harm of the pandemic, schools will have to navigate the loss of this crucial funding while simultaneously contending with higher labor costs.

DCFPI encourages the DC Council to ensure that all schools can absorb growing labor costs in their budgets. Additionally, DCPS should publish data on which ESSER-funded resources were most effective so lawmakers can create a plan to use local revenue to meet the ongoing needs of students and ensure school stability.

Initial School Budgets Violate the Law and DCPS’s Inconsistent Budget Practices May be Undermining Educational Equity

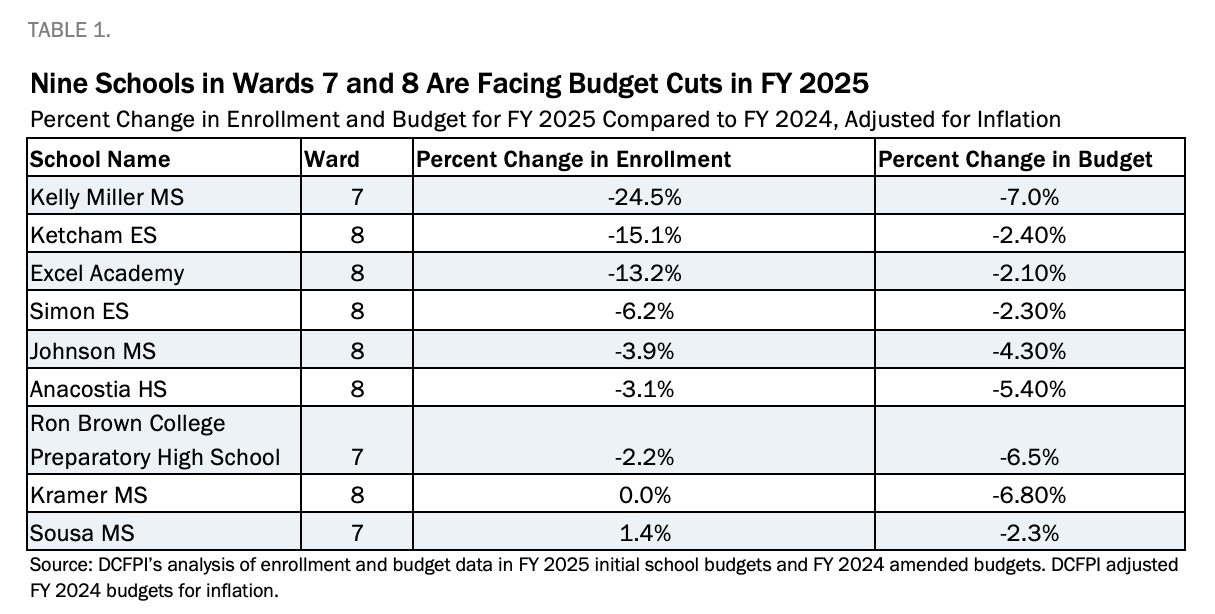

Three schools in Ward 7 and six schools in Ward 8 are facing budget cuts in FY 2025, when adjusting for inflation (Table 1, pg 3), despite the Schools First in Budgeting Amendment Act’s (Schools First) requirement that DCPS fund schools at least at the level of their prior year budget, with some exceptions.[5] Of these nine schools, four are projected to have a budget cut of more than 5 percent, even though they are receiving stabilization funds designed to keep cuts below that threshold. For some schools, the drop in funding appears to be enrollment driven, but there is not a clear pattern across schools. This suggests potential inconsistencies in how DCPS applies its school funding model. Failing to consistently follow the funding model undermines educational equity and harms Black and brown students.

Schools are particularly sensitive to enrollment drops because most of their budget is based on an enrollment formula, so as enrollment declines, funding can too.[6] Schools First also requires schools to stabilize staff in response to enrollment changes. For example, if a school’s enrollment is projected to decline, then any staff cuts must mirror the trends in enrollment[7],[8] DCFPI encourages DCPS to increase transparency on how budget decisions are made, particularly for schools receiving budget cuts. Increased transparency will give schools a better long-term outlook regarding budgets.

Initial School Budgets Include a Worthy Jump in “At-Risk” Funds

It is essential that schools have funding to best serve students who are furthest from opportunity. FY 2025 initial school budgets include a significant $26 million increase in funding for students “at-risk of academic failure” in Wards 5, 7, and 8.[9] By law, schools must use “at-risk” dollars to supplement, rather than supplant, a school’s budget, as these funds are meant to provide additional supports. In the past, DC schools have violated this law, shortchanging students who need extra funds the most.[10] Underfunding schools at the base level makes it likelier that schools will rely on these supplemental dollars to fund general functions, such as a general education teacher, even if it is against the law.

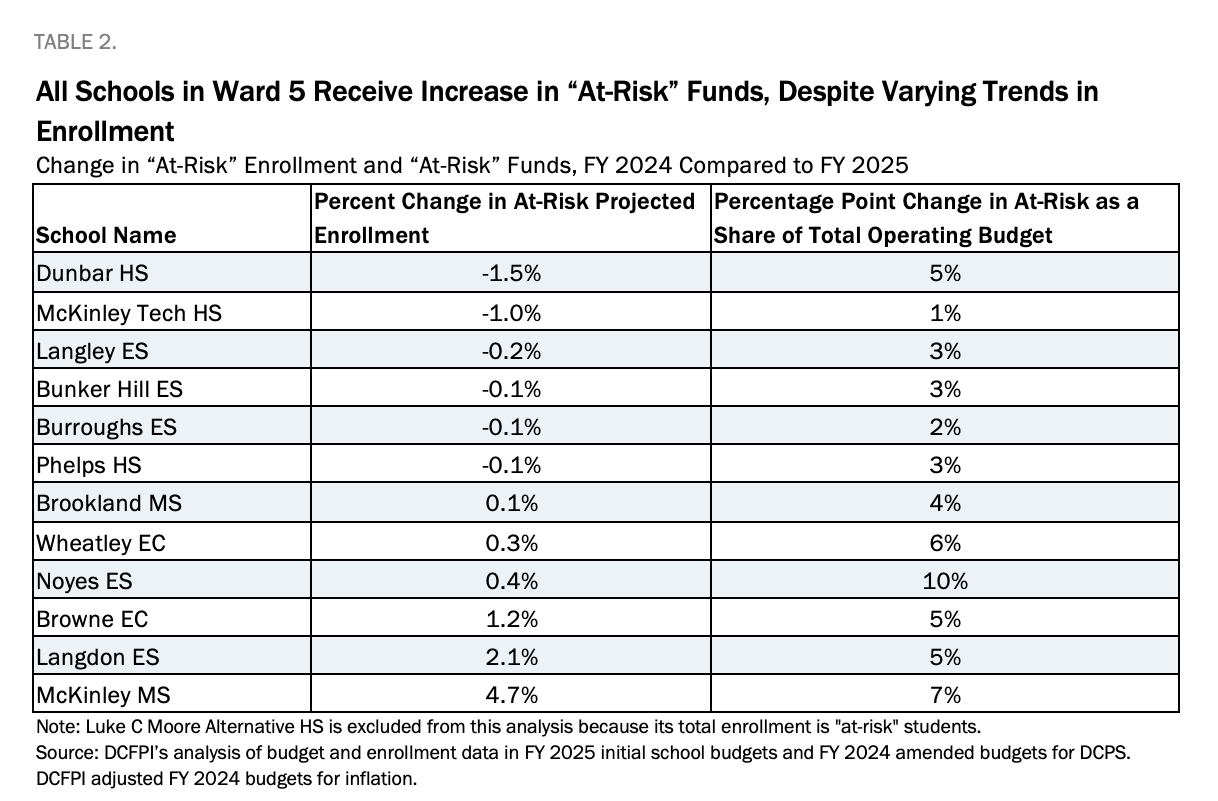

In FY 2025, “at-risk” dollars make up 13, 15, and 19 percent of initial school budgets in Wards 5, 7, and 8, respectively.[11] “At-risk” dollars as a share of a school’s total operating budget are increasing across schools in these wards, even though some schools are losing “at-risk” students (Table 2, pg 4). The current format of publicly available budget documents makes it difficult for the public to discern why and how a school’s “at-risk” budget could be increasing even if enrollment is growing or remains unchanged.

Accountability and transparency into how schools are spending “at-risk” dollars remains a priority. DCPS should document how these funds are supplementing school budgets and meeting the requirements in the law when they release initial school budgets.

Policymakers Must Create a Plan to Invest in By-Right Neighborhood Schools

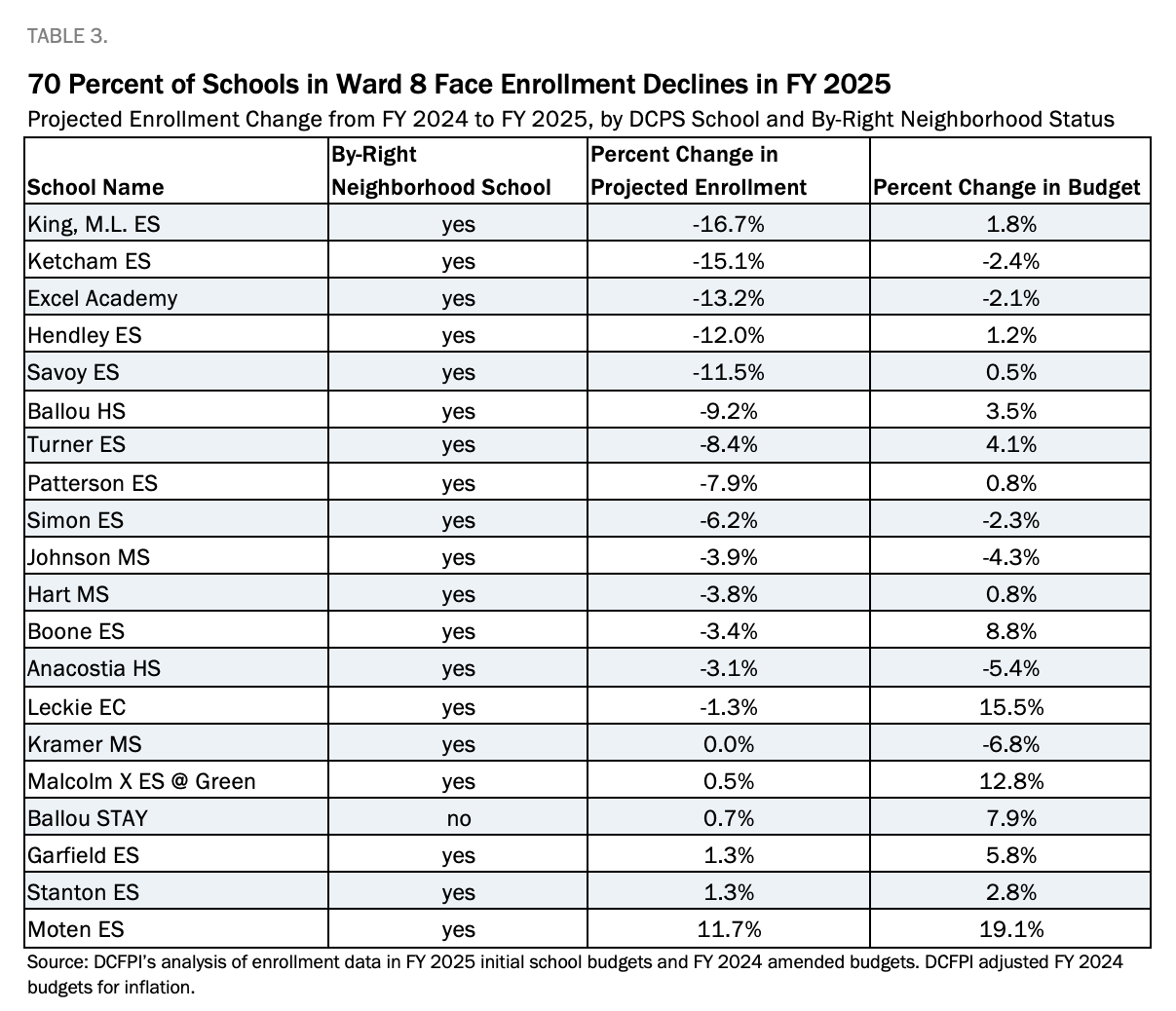

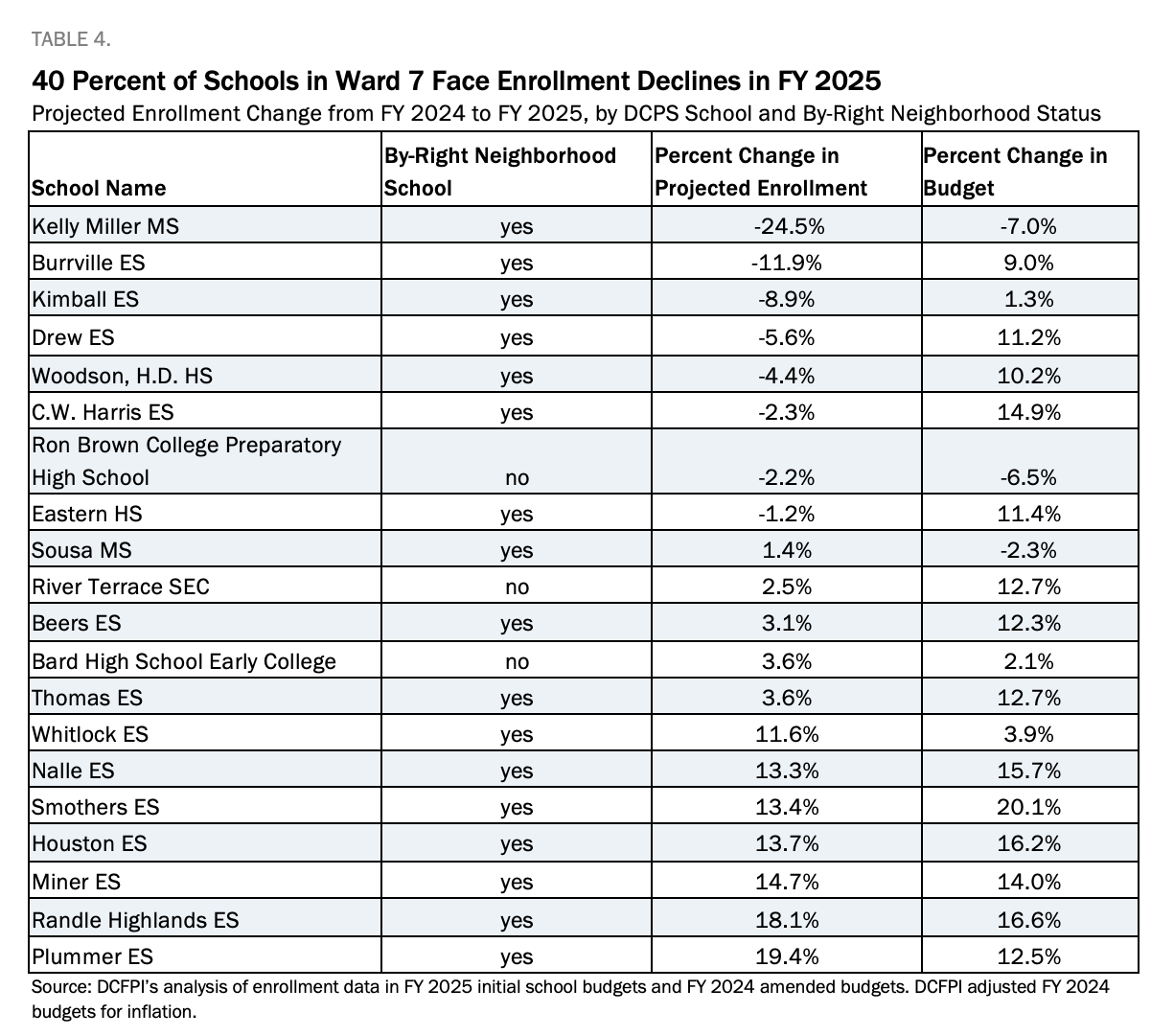

By-right neighborhood schools, particularly those east of the Anacostia River, have faced declining enrollment for years, resulting in underutilized and under-resourced schools. In FY 2025, 40 percent of schools in Ward 7 and 70 percent of those in Ward 8 are projected to see declines in enrollment, and across both wards 95 percent of schools with enrollment declines are by-right neighborhood schools (Tables 3 and 4, pg 5).

Continuous enrollment declines in Wards 7 and 8 have resulted in a disproportionate number of small schools in these wards.[12] These schools are more expensive to operate and have an unfair burden of fixed costs relative to medium sized schools throughout the District.[13] When enrollment-based funds decrease, principals of small schools are forced to cut programs and resources that have helped students thrive.

DCFPI has previously testified on the issue of enrollment declines and continues to support the exploration of a supplemental weight through the Uniform Per-Student Funding Formula for small by-right neighborhood schools.[14] This could help these small schools to afford valuable positions that larger schools offer, such as music teachers and after-school programs.

To truly address school budget stability, DCFPI urges the mayor, DC Council, and education officials to articulate and demonstrate an equitable vision for and commitment to neighborhood schools. They should consider the ongoing needs of school communities to ensure critical programs and positions are resourced in FY 2025. Failure to implement a school budget model that ensures stability undermines the goal of educational equity throughout the District.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify. I am happy to answer any questions.

[1] The FY 2025 initial school budgets are the first time higher salaries from past negotiations appear in school budgets; not to be confused with current negotiations.

[2] DCPS reported this data in its catalog, which describes which positions are required and cannot be changed (level 1,) required but flexible (level 2,) and fully flexible (level 3.) Positions not included in level 1, 2, or 3 are non-allocated and up to school leaders to use discretionary and flexible funding. For more information, see: FY25 Budget Development Guide, District of Columbia Public Schools, Accessed February 14, 2024.

[3] DCFPI’s analysis of DCPS’s FY 2024 amended school budgets and FY 2025 initial school budgets.

[4] DCFPI’s Analysis of the Office of the Superintendent of Education’s LEA ESSER Dashboard. ESSER dollars were allocated to LEAs starting in FY 2020 and ending in FY 2024.

[5] The Schools First in Budgeting Amendment Act of 2022 limits cuts to 5 percent but does not mention whether the calculation should be based on inflation adjusted figures. Given adjusting the figures for inflation is more accurate, DCFPI adjusts FY 2024 budgets for inflation in this analysis.

[6] DCPS’s budget model determines a school’s budget based on three categories of funding: enrollment-based funds, targeted support funds, and stability funding. To learn more, see: DC Fiscal Policy Institute, “How DC Funds its Public Schools,” January 2024.

[7] “Schools First in Budgeting Amendment Act of 2022,” Act No. 24-785, March 10, 2023.

[8] DCPS requires one general education teacher to every 26 students.

[9] DCFPI Analysis of DCPS FY 2025 Initial Budgets.

[10] Erin Roth and Will Perkins, “DC Schools Shortchange At-Risk Students,” Office of the District of Columbia Auditor, June 26, 2019.

[11] “At-risk” dollars include the at-risk school-based budgeting concentration weight, at-risk uniform per student funding formula, at-risk school-based budgeting concentration, and at-risk uniform per student funding formula overage amounts.

[12] The Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education defines small schools as elementary schools with a total enrollment of less than 300 students, middle schools with less than 400 students, high schools with total enrollments less than 500 students, and all other schools with total enrollment less than 300 students.

[13] Forthcoming analysis from DC Fiscal Policy Institute.

[14] Qubilah Huddleston, “Initial School Budgets Show DCPS Needs a Plan to Ensure Equitable Funding and Stability,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, February 24, 2023.