This report is part of a series of research and analysis on how DC can build a tax system that embodies racial justice in both its design and the public investments it provides. Find the full series here.

A history of racist policy and practice and its ongoing effects has resulted in tens of thousands of Black and brown children growing up in families experiencing economic hardship. DC has made great effort to provide economic supports to families that struggle, but the magnitude of racial inequity in the District requires that more be done to shore up the cash resources of Black and brown families, particularly those with low to poverty-level incomes.

The District can build on its efforts to increase basic incomes through the DC Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and various pilot programs that guarantee income with a local Child Tax Credit (CTC). A District level CTC targeted to families up to 300 percent of the federal poverty line (FPL, about $90,000 for a two-parent family of four) would reach nearly 80,000 children, including tens of thousands no longer eligible for the federal CTC. If large enough, the DC credit could substantially reduce child poverty, especially among Black children, who are the vast majority of children living in poverty in DC. A CTC not predicated on work could help to deliver much needed economic support to families with children facing the steepest barriers to employment, reducing income inequality at the lowest levels of income, while aiding families with children to meet basic needs.

It also can help families with low and moderate incomes relative to the extremely high cost of living in DC better afford the costs of raising children. Doing so leaves these families more resources to invest in the well-being and futures of their children and to help set the District on a path to a racially-just future where truly every child has a chance to live to their fullest.

Summary:

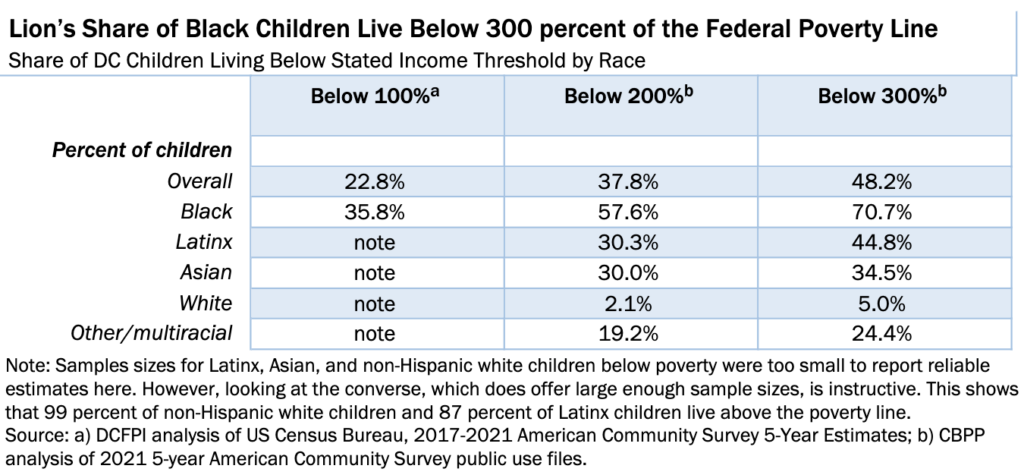

- Child poverty is higher in DC (22.8 percent) than nationally (17 percent). Because of systemic racism, more than one-third of Black children live in poverty.

- Poverty—especially when it’s persistent—has long-lasting negative effects on children and their well-being in adulthood. Boosts to cash income, conversely, helps children from families that are poor and low-income do better and go further in school, and work and earn more as adults.

- Congress’ expansion of the federal Child Tax Credit lifted or eased poverty for 25,000 children in the District.

- A $1,500 per child credit for DC, available to all children ages 17 or under regardless of immigration status, would reach 80,000 children and lift 4,700 from poverty.

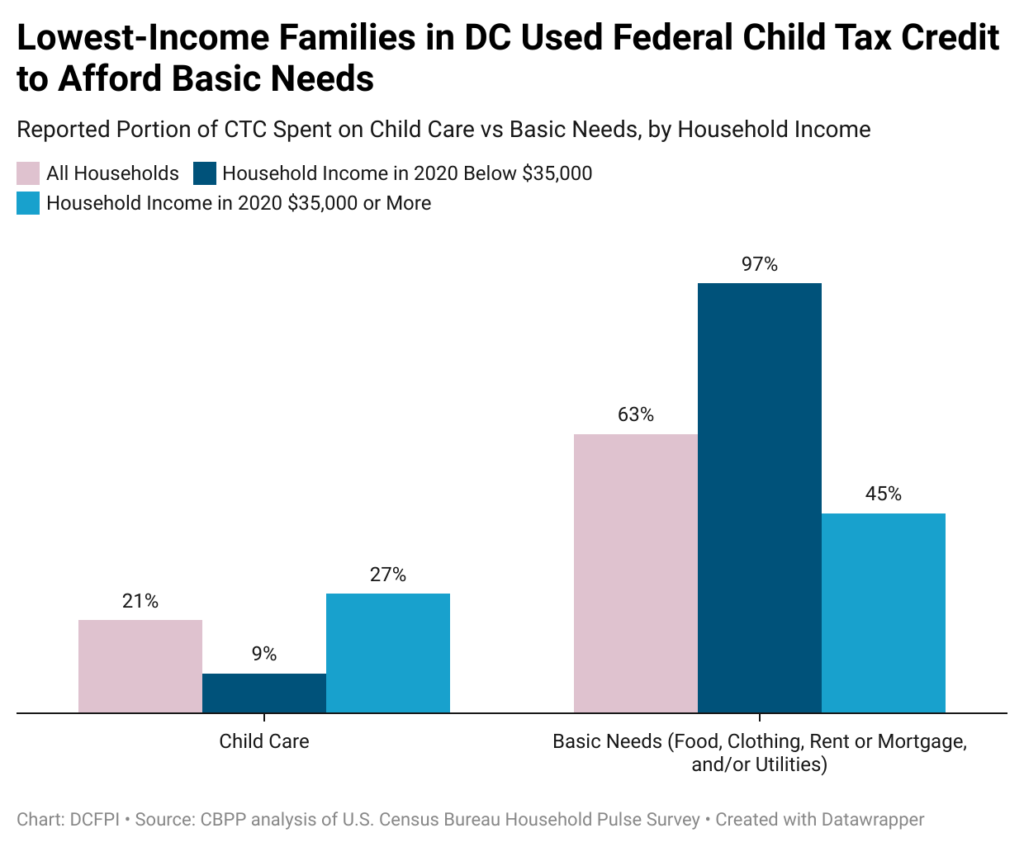

- Nearly two-thirds of all households in the District and 97 percent of those with incomes below $35,000 receiving federal CTC payments reported using those dollars to pay for basic needs like food, clothing, rent, and utilities. About one-fifth of households receiving CTC and more than one-quarter of those with incomes above $35,000 used the credit to help cover child care expenses.

- A child tax credit not predicated on work would help parents facing the steepest barriers to employment meet their families’ basic needs.

Child Poverty and the Benefits of Income

Poverty and economic hardship have deep, long lasting effects on children and their lives, especially if it begins in their early years and persists over a long period of their childhood.[1] Parents with low incomes are less able to provide their children the things they need to flourish. They may struggle to provide nutritious meals or enriching learning environments in the home, or they may lack the means to access high quality child care. Parents with little income also carry enormous stress of how to pay the rent, buy food, and other necessities, and for some, of living in less healthy or safe neighborhoods. All of this affects the environment in which children grow and develop and has been shown to impede how well and how far children do in school, and how much they work and earn as adults.

Nationally, nearly 40 percent of children experience at least one year of poverty before they turn 18, with nearly 11 percent experiencing persistent poverty, according to longitudinal research by the Urban Institute.[2] Stark differences by race mean that three out of four Black children experience at least one year of poverty, more than half of them persistently, compared with three in ten white children and far fewer (4 percent) persistently. The same study finds that children who are poor for longer do less well than those who are poor for just one year. They are less likely to graduate from high school, attend college, or complete college; less likely to have consistent employment as adults; and more likely to have teen births. That Black children are more likely to be poor and persistently poor than children overall, and white children in particular, means that Black people experience wider spread intergenerational barriers to success. It also suggests that shortening the length of child poverty matters to disrupting cycles of poverty.

Snapshot of DC’s Child Poverty Shows Stark Differences in Childhood Well-Being for Black and White Children

Child poverty is higher in DC than nationally and disparities between the well-being of Black children compared with white children are extreme. Overall, about 23 percent of children in DC live below the federal poverty line, around $30,000 for a two-parent family of four, according to US Census data.[3]

Black children also are the large majority of children living in families that are poor (85 percent), living in families with low incomes (81 percent), and living in lower middle-income families (77 percent).[4] White children make up just 1-2 percent of these groupings.

With the prevalence of poverty among Black children (younger and older) in DC, and given the long reach of poverty and its effects on children fare when they grow into adults, it is not surprising to see persistently high poverty rates among Black residents. The level and racially disparate experience of poverty in the District underscores the desperate need for more intentional investments in children to stem the tide.

Income Changes Life Trajectories

Getting cash to families that are poor and low-income can make a long-lasting difference in children’s lives and how they fare as adults. For example, a longitudinal study of federal EITC increases on child outcomes found that a $1,000 increase in family income from the credit raised math and reading test scores for children and resulted in higher earnings in their adulthood.[5] Another study showed that for families with young children with incomes below $25,000, an income boost of just $3,000 would result in a 17 percent increase in adult earnings for those children.[6] Boosts to income also can help children access higher education by making college or the costs of attendance more affordable. One study showed that as little as $1,000 could increase the likelihood of high school seniors enrolling in college, for those in families with incomes low enough to qualify for the maximum federal EITC benefit.[7] And, EITC, CTC, and other boosts to cash income may improve health by way of increased educational attainment.[8]

Increased income for families living in poverty also has been shown to improve health more directly as well. For example, one study found that EITC income reduced low-weight or premature births, especially among Black children; relatedly, the additional income helped reduce smoking among pregnant mothers and increased prenatal care at critical times during pregnancy.[9] Some studies suggest that cash income like that from refundable tax credits enable struggling families to spend more on food and healthier foods, which helps with healthier development of children. Other research shows the additional cash income improves health through reduced stress.

Increasing incomes to reduce poverty also would benefit the economy more broadly. One study looking at disparities in innovation—an important economic driver—by race, gender, and income, finds that if children in the bottom 80 percent of the income distribution in DC were to grow up to invent at the same rate as children from the top 20 percent, the District would have five times as many children growing up to be inventors.[10] In other words, if income inequality were eliminated, we’d have more people driving the future of our economy and, moreover, these people would come from more diverse backgrounds that bring new perspective to new innovations. Another study found that even in the short-run, economic supports can help people with entrepreneurial ideas take risks and pursue those ideas.[11] One study estimates that the costs of child poverty to the national economy at over $1 trillion per year, or 5.4 percent of gross domestic product (a measure of our economic output) because it depresses economic productivity, increases costs of crime, health care, child homelessness, and child welfare.[12] That means the economy could be strengthened substantially if policies greatly reduced or eliminated poverty.

Expanded Federal CTC Brought Major Benefits to Children and Families in DC

The federal EITC and CTC together make up the most powerful tools that the US has for reducing poverty, second only to Social Security.[13] Prior to the pandemic, the credits lifted 16 million people, including 5.5 million children, out of poverty (relative to the Supplemental Poverty Measure[14]) and eased economic hardship for millions more. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) temporarily expanded the CTC in ways that increased its reach and impact, making it an even more effective companion to the EITC and at a time when Black, brown, and immigrant families living on low incomes were reeling from the health and economic harms of the pandemic.

Under ARPA, lawmakers expanded the CTC in multiple ways.[15]

- Made the credit fully refundable to families with little to no income.

- Increased the maximum per child benefit to $3,600 for children under age 6 and to $3,000 for children 6 and older for families with children with incomes below $112,500 for single parents and $150,000 for married couples.

- Implemented a phaseout to the original $2,000 per child maximum benefit, which begins to phase out at $200,000 for single parents and $400,000 for married couples.

This expansion had an incredible, positive impact on families and children in the District, pushing against racial and ethnic inequities that have left Black and brown children more likely to grow up in economic hardship. For example, the credit cut DC’s child poverty rate by more than half, according to Urban Institute analysis of the expansion.[16]

- Lifted from or eased poverty for 25,000 children in the District.

- Benefitted 93,000 District children whose families receive only partial credit or no credit under non-expansion parameters.

- Reached 32,000 Black children and 6,000 Latinx children in the District, who are now no longer eligible for the credit under current, non-expansion parameters.[17]

A local CTC can have similar antipoverty effects and ensure that these children and their families have access to much needed economic support. Nearly two-thirds of all households in the District and 97 percent of those with incomes below $35,000 receiving federal CTC payments reported using those dollars to pay for basic needs like food, clothing, rent, and utilities (Figure 1). About one-fifth of households receiving CTC and more than one-quarter of those with incomes above $35,000 used the credit to help cover child care expenses.[18]

A Local CTC Would Build on the EITC to Reach More Children From DC’s Poorest Families

There are several reasons that the District should adopt a CTC to complement its EITC. In addition to reducing poverty and hardship, helping families meet basic needs, and positively shaping children’s futures, the EITC does incredible work reducing income inequality between Black and white people at the 50th and 25th income percentiles of the income distribution, or those with moderate incomes.[19] According to recent research, that’s largely because of the way it induces more work. However, the EITC does not reduce inequality at the 10th percentile—the very lowest income levels—likely due to the steep, persistent barriers to employment faced by Black people in the United States.[20] These findings point to the limits of a work-focused cash transfer for reducing inequality for the most disadvantaged Black residents, who because of structural racism, experience enormous and entrenched barriers to stable employment and a much lower likelihood of savings or other financial supports to leverage when falling on tough times.

The District has one of the highest Black unemployment rates in the country and the very highest Black to white unemployment ratio; it also has a massive gap between white and Black median household incomes and wealth.[21] A child tax credit not predicated on work could help to circumvent that issue, delivering much needed economic support to those facing the steepest barriers to employment, reducing income inequality at the lowest levels of income, while aiding families with children to meet basic needs. New research on the effects of the federal CTC in fact show no negative effects of unconditional cash on the labor market participation of recipients.[22] That means the CTC can buoy families with children, improve the life chances of children, and without discouraging work.

A second reason for adopting a local CTC is that the federal credit is limited in its reach. Congress let expire the temporary expansion to the federal CTC, which allowed it to reach tens of thousands more children in the District whose families have no income for the first time ever and provided a much more robust credit to families with very little income. A District CTC would ensure that families with children struggling the most also receive aid in covering the costs of raising children, and it could help to stem the intergenerational cycle of poverty holding families back.

Finally, DC’s other major cash transfer program for the very poorest families—Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance—is limited in size and reach and, despite the District’s removal of time limits and certain family sanctions, its design is rooted in anti-Black racism painting Black mothers as lazy, cheats, and unworthy of public supports.[23] In 2022, DC TANF benefits equaled just 35 percent of the federal poverty line, with a 12 percent decline in value since the 1996 national welfare reform that created the program.[24] And as of July 2022, the maximum benefit for a single parent family of three was just $655 per month, or $7,860 per year.

A $1,500 Per Child Credit for DC Would Reach 80,000 Children and Lift 4,700 From Poverty

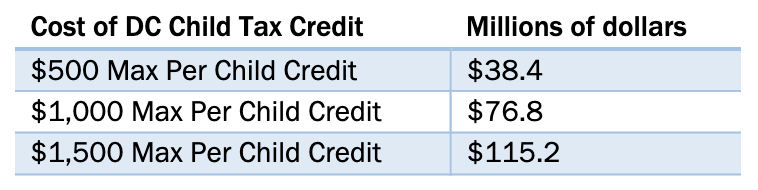

At the DC Fiscal Policy Institute’s (DCFPI) request, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) modeled the impact and cost of three credit sizes—$500, $1,000, and $1,500—under the following parameters:[25]

- Available to all children aged 17 and younger,[26] including children in families filing taxes with an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number;

- No cap on the number of eligible children per family;

- Available to all families with incomes between $0 and 300 percent of FPL;

- Phaseout of the credit begins at 200 percent of FPL and ends at 300 percent FPL; and

- Inflation adjusted, as done with the federal CTC.

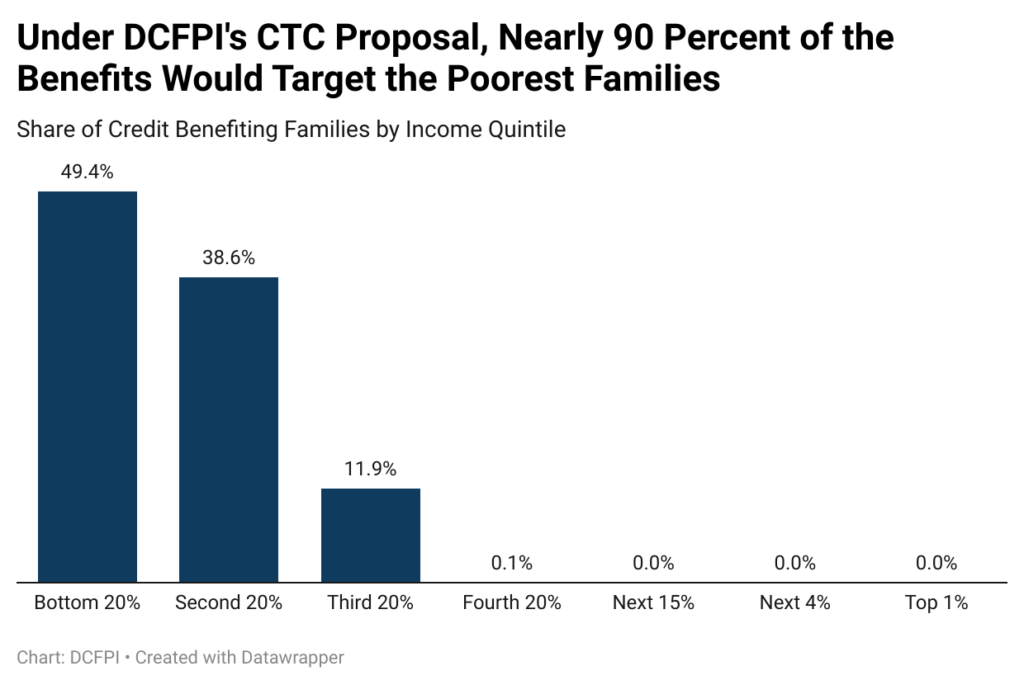

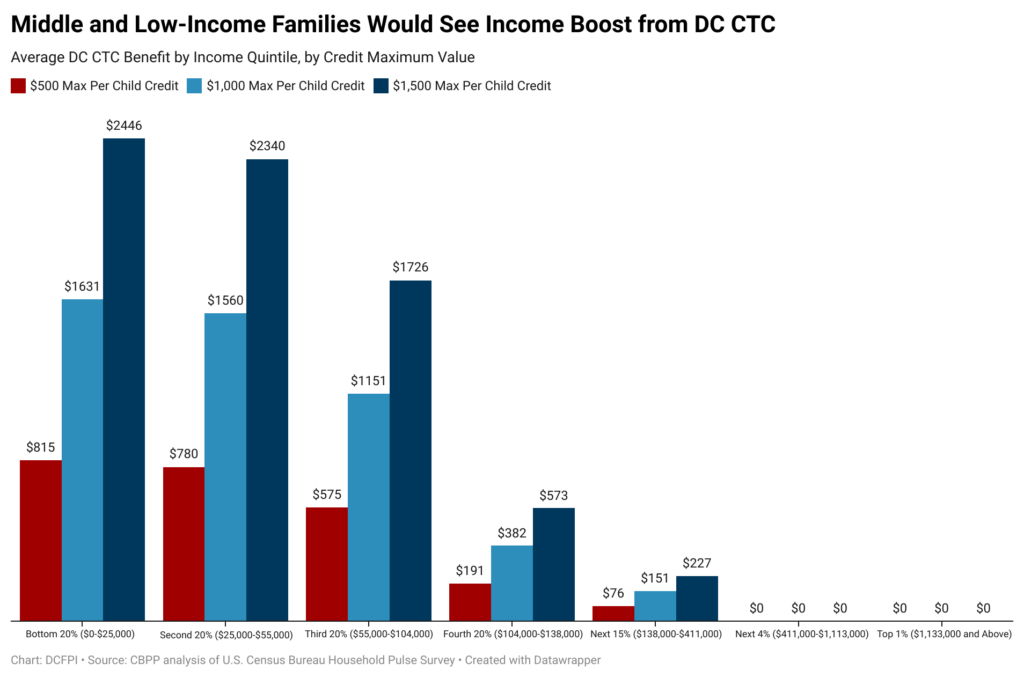

The cost of a local CTC with these parameters would range from $38.4 million to $115 million, depending on the maximum credit size (Table 2).[27] Regardless of credit size, a CTC designed as proposed here would reach nearly 80,000 children, including all children living below the poverty line. Nearly 90 percent of the tax benefit would go to families earning below $55,000, or those in the bottom two fifths of the income distribution (Figure 2). Another 12 percent of the benefit would go to families with income between $55,000 and $104,000. Because of this targeting, the large majority of children benefitting would be Black, followed by Asian and Latinx children.

Using the $1,500 per child scenario as an example, the average credit for the children in families below $25,000 (the bottom fifth of incomes) would be nearly $2,500 (Figure 3, pg 10). For the next quintile, with incomes below $55,000, it would be about $2,300. The middle quintile with incomes below $104,000, would receive, on average, $1,700. The credit could be modeled after the DC EITC and paid out monthly to help smooth out family finances if the credit amount surpasses a particular threshold, which is currently $1,200 for the DC EITC.[28]

ITEP also requested estimates of the poverty reduction effects of the largest credit size from the Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University (CPSP). CPSP found that a $1,500 per child credit for DC would reduce child poverty by 18 percent, or lift 4,700 children out of poverty, relative to the Supplemental Poverty Measure. Hardship would be eased for tens of thousands more children. For moderate and lower middle-income families, the credit would also lower the taxes they pay as a share of their income, making the District’s tax code more progressive and helping these families invest in their children’s futures.

These positive effects amount to a strong move for racial justice. DC should build on its current tools and adopt a CTC to:

- Reduce poverty and hardship and improve outcomes for children, especially Black children who make up the vast majority of poor and low-income children in DC.

- Build on DC’s investments in basic income, especially for families with major barriers to work and little to no access to DC’s EITC.

- Offset the high costs of caring for a child for low- and middle-income families, especially Black families that comprise the lion’s share of children in families at two and three times the poverty line.

[1] For a thorough review of the literature, see National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. “Chapter 3: Consequences of Child Poverty.” A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25246.

[2] Caroline Ratcliffe, 2015, Child Poverty and Adult Success, Urban Institute.

[3] DCFPI analysis of US Census Bureau, 2017-2021 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates and Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of 2021 5-year American Community Survey public use files.

[4] Data not shown. DCFPI analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, 2017-2021 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates and CBPP analysis of 2021 5-year American Community Survey public use files.

[5] Gordon Dahl and Lance Lochner, March 1, 2016, “Correction and Addendum to ‘The Impact of Family Income on Child Achievement: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit.”

[6] Greg J. Duncan and Katherine Magnuson, “The Long Reach of Early Childhood Poverty,” Pathways, Winter 2011.

[7] Dayanand S. Manoli and Nicholas Turner, “Cash-on-hand and College Enrollment: Evidence From Population Tax Data and Policy Nonlinearities,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 19836, revised April 2016.

[8] For a thorough review of the literature on the health benefits of income support, see Arloc Sherman, Samantha Waxman, and Kris Cox, 2021, Income Support Associated With Improved Health Outcomes for Children, Many Studies Show.

[9] Hilary W. Hoynes, Douglas L. Miller, and David Simon, “The EITC: Linking Income to Real Health Outcomes,” University of California Davis Center for Poverty Research, Policy Brief, 2013 and Kelli A. Komro et al., “Effects of State-Level Earned Income Tax Credit Laws on Birth Outcomes by Race and Ethnicity,” Health Equity, March 13, 2019.

[10] Wesley Tharpe, Michael Leachman, and Matt Saenz. December 9, 2020. Tapping More People’s Capacity to Innovate Can Help States Thrive. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

[11] Gareth Olds. June 2016. “Food Stamp Entrepreneurs.” Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 16-143. This study finds that one of the things that holds back entrepreneurship is the risk of leaving wage employment to pursue ideas, and having income supports (or economic supports that mimic income like food stamps) help lessen that risk.

[12] See summary starting on page 89 in National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. “Chapter 3: Consequences of Child Poverty.” A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; McLaughlin, M., and Rank, M.R. 2018.Estimating the economic cost of childhood poverty

in the United States. Social Work Research, 42(2), 73–83.

[13] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. December 7, 2022. Policy Basic: The Child Tax Credit.

[14] The Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) is an alternative to the official poverty measure (OPM) that allows researchers and advocates to 1) gauge the impact of various forms of assistance in calculating income and 2) set a threshold based on a fuller range of living expenses, including housing. Nationally, this measure shows a dramatically lower poverty rate than the OPM (7.8 percent compared with 11.6 percent) in 2021. Three-year averages offered at the state level show that the poverty rate in the District is roughly the same across the two measures, or about 14.6 percent. That likely means that some of the robust economic supports like the federal and District level EITCs are offset by household expenses like extremely high housing costs. However, we know the programs not captured in the official poverty measure make a difference. Analysis from the Urban Institute earlier this year, for example, showed that child poverty in the District as measured by the SPM was reduced by more than half due to the (now expired) expansion of the Child Tax Credit under the American Rescue Plan Act.

[15] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. December 7, 2022. Policy Basic: The Child Tax Credit.

[16] Gregory Acs and Kevin Werner. July 2021. How a Permanent Expansion of the Child Tax Credit Could Affect Poverty. Urban Institute.

[17] Kris Cox et al. December 3, 2021. If Congress Fails to Act, Monthly Child Tax Credit Payments Will Stop, Child Poverty Reductions Will Be Lost. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; Chuck Marr et al. December 7, 2022. Year-End Tax Policy Priority: Expand the Child Tax Credit for the 19 Million Children Who Receive Less than Full Credit. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

[18] CBPP analysis of U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey public use files for survey weeks 34-36. Data collected July 21, 2021 – August 30, 2021 (period covering the first two monthly CTC payments).

[19] Bradley Hardy, Charles Hokayem, and James P. Ziliak. 2022. Income Inequality, Race, and the EITC. National Tax Journal, vol. 75, no. 1, March 2022.

[20] Ibid; also see Lincoln Quillian et al., “Meta-analysis of field experiments shows no change in racial discrimination in hiring over time,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, August 8, 2017, .

[21] Economic Policy Institute, State Unemployment by Race and Ethnicity for Quarters 2 and 3 of 2022, December 2022.

[22] Natasha Pilkauskas et al. October 2022. “The Effects of Income on the Economic Wellbeing of Families with Low Incomes: Evidence From the 2021 Expanded Child Tax Credit,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 30533; Elizabeth Ananat et al. March 2022. “Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Employment Outcomes: Evidence from Real-World Data from April to December 2021,” NBER; Leah Hamilton et al. April 2022. “The impacts of the 2021 expanded child tax credit on family employment, nutrition, and financial well-being: Findings from the Social Policy Institute’s Child Tax Credit Panel (Wave 2).” Brookings Institution.

[23] Ife Floyd et al. August 4, 2021. TANF Policies Reflect Racist Legacy of Cash Assistance. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

[24] Gina Azito et al. February 3, 2023. Increases in TANF Cash Benefit Levels Are Critical to Help Families Meet Rising Costs. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

[25] ITEP’s model uses five-year estimates from the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (2015-2019) as well as data from other US data agencies.

[26] At the federal level and in many states, CTCs offer a larger credit or boost for younger children because of the importance of children’s first years in life to their life outcomes and because there aren’t that many investments in this country’s youngest children. However, research also speaks to the importance of addressing poverty for older children and for shortening the length of time that children experience poverty. DCFPI chose not to include a boost for younger children given that child poverty in DC is higher among older children than younger children, which is different than the national picture or what is typical among other states. About 24 percent of children over age 6 in DC are poor compared with 20 percent of those that age or younger. Policymakers may want to consider a future expansion that offers a boost for younger children.

[27] A new paper by CBPP estimates the cost of a DC EITC with somewhat different parameters than DCFPI’s proposal, and their estimate falls into the ballpark of DCFPI’s mid-level estimate for a $1,000 per child credit. The estimates differ for several reasons, including higher phaseout ranges and a $500 boost for young children. The CBPP estimate assumes a lower take up rate of a new credit and uses three-year pooled data from the American Community Survey and shows costs in 2022 dollars. See: Samantha Waxman and Iris Hinh, States Can Enact or Expand Child Tax Credits and Earned Income Tax Credits to Build Equitable, Inclusive Communities and Economies, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, . March 3, 2023.

[28] If lawmakers chose to include a provision for monthly payment of the credit, they also should adopt an “opt-out” clause for any families that might see reduction or loss of federal public benefits that may consider monthly payment of a local CTC as regular income in benefit eligibility determinations.