Chairperson Mendelson and members of the committee. My name is Michael Johnson Jr, State Policy Fellow with DC Fiscal Policy Institute. DCFPI is a non-profit organization that shapes racially-just tax, budget, and policy decisions by centering Black and brown communities in our research and analysis, community partnerships, and advocacy efforts to advance an antiracist, equitable future.

My testimony focuses on the need for the District to ensure every student has access to a quality neighborhood school and prioritize them as foundational community institutions—particularly in historically segregated and divested communities. DCFPI recommends that the Deputy Mayor for Education (DME):

- Stabilize enrollment in neighborhood schools—which are important community institutions—by rejecting plans to open new citywide schools. DC should focus on adequately and equitably supporting neighborhood schools to thrive, particularly those in historically divested areas.

- Adopt an explicit plan to right size student migration patterns across geographic boundaries; and,

- Facilitate meaningful community engagement within the Master’s Facilities Plan and Student Assignment & Boundary Zone Study.

Stabilizing Enrollment in Neighborhood Schools Should be a Top Priority

DME Paul Kihn has warned many times that the District is on a dangerous path of unintentionally ‘small schools’ in recent years. Small schools are more expensive to maintain, placing greater pressure on the overall education budget and individual schools themselves. Policymakers must pay closer attention to the combined effect that large and sustained swings in enrollment, school openings, and school choice have on educational equity.

Public school enrollment, on net, is increasing by 3 percent in the District compared to last year, but the distribution of that growth is vastly uneven across wards. DC Public Schools (DCPS) projects that the majority of schools in Wards 7 and 8 are expected to experience enrollment declines, as my colleague Qubilah Huddleston testified last week.[1] For example, DCPS projects that enrollment at schools in Wards 7 and 8 will decline by over 500 students combined compared to last year—with schools such as McKinley Middle School, Bard High School, Excel Academy, and Kramer Middle School expected to lose almost a quarter of their enrollments.[2]

DCPS uses a student-based budgeting model in which each school’s budgets are directly tied to the number and characteristics of students enrolled. As a school loses students, the funding allocated to each student leaves with them and follows them to their newly assigned school. Yet, there are many operational costs that schools still face even when they experience enrollment declines, making it more expensive for small schools to operate. For example, a middle school that is projected to lose a dozen students in a year across grade levels will likely face a budget reduction, yet the school may be unable to cut a teaching position for a given grade level. Another example is custodial staff. Building maintenance and cleaning needs are driven by the size or square footage of the building and school type in addition to the number of students attending the school. Therefore, even when schools are projected to lose students and lose funding, they cannot just cut custodial staff without meaningful consequences for the health and safety of students and educators in their buildings.

Although the Mayor and DC Council included stabilization and recovery funding within the FY 2023 and FY 2024 DCPS school budgets to mitigate the harm of sustained enrollment declines associated with the pandemic, this funding provides only short-term relief for schools experiencing sustained enrollment losses. Moreover, declining birth rates could place even greater fiscal constraint on neighborhood schools over the long term. As fewer children are born each year, it reduces the overall number of students that are available to enroll in DC’s public schools in future years, assuming there aren’t significant population gains. Since 2016, both the number of births and the ratio of births to DC residents has declined each year, likely contributing to lower enrollments in elementary school grades.[3] This is especially harmful for neighborhood schools in Ward 8, which have had the sharpest declines in birth rates as there were an estimated 15 percent drop in births in 2020 compared to 2016.[4]

Given the enrollment challenges facing many of the Districts public schools, DCFPI urges the DME to identify policies that can stabilize enrollment in neighborhood schools and equitably support them to thrive, particularly those in historically divested areas.

Adopt an Explicit Plan to Right Size Student Migration Patterns across Geographic Boundaries

Policymakers can stabilize neighborhood schools by rejecting plans to open new citywide schools. Most of school growth is occurring in areas where neighborhood schools are already struggling the most to maintain enrollment—in Wards 5, 7, and 8—even though these are the parts of the District with the highest number of unfilled seats and lowest boundary participation rates (defined as the percentage of students living in a school’s boundary that attend that school). DC is building schools even as classrooms sit half empty—and it’s harming Black and brown students the most while squeezing DC’s finite resources.

While there has been growth among both the number of DCPS and charter schools, charter schools account for 82 percent of the newly opened schools districtwide within the last five school years—most heavily concentrated in Wards 5, 7 and 8.[5] Of the 33 public schools opened during that period, two thirds opened their doors in Wards 5, 7, and 8.[6]

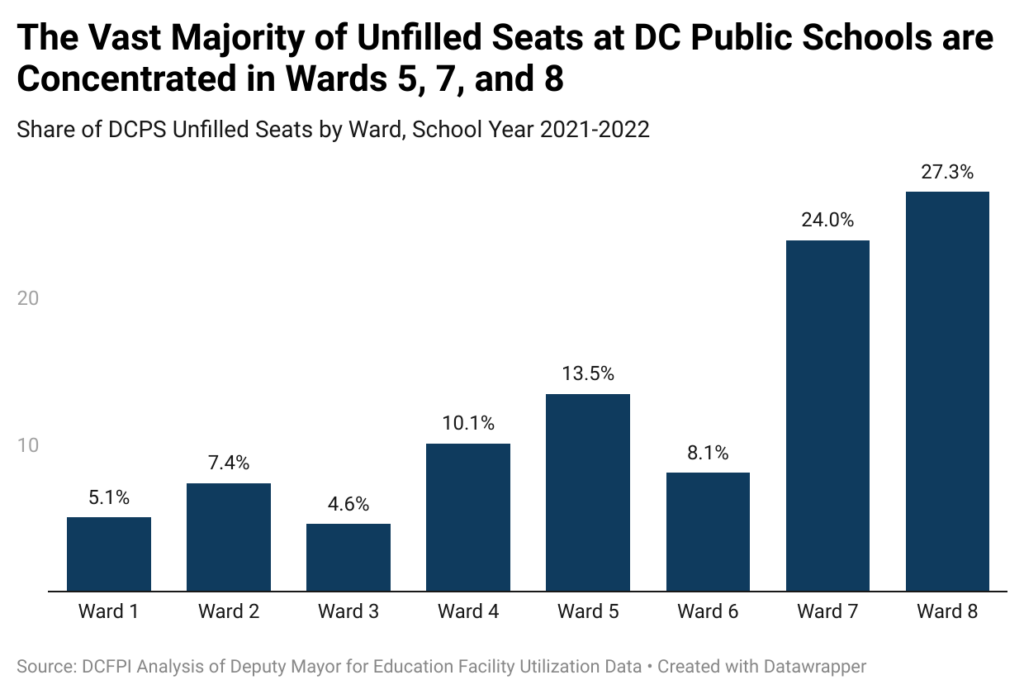

The growth of new schools is occurring against the backdrop of inequities and policy choices that are creating greater preference and demand for schools in wealthier, whiter parts of the District. DC is facing under-enrollment of neighborhood schools in historically underinvested communities and over-crowding of schools in wealthier communities. Of the 21,731 unfilled seats within DCPS in school year (SY) 2021-22, 65 percent were in schools in Wards 5, 7 and 8 (Chart 1).[7][8] Additionally, the schools experiencing severe under-utilization (defined as schools with enrollments less than 50 percent of their programmatic capacity) are most vulnerable to reduced program offerings produced by budget cuts, or even worse, closures.[9] Alarmingly, 16 out of the 20 DCPS schools that are severely under-utilized are in Wards 5, 7, and 8.[10] This is not exclusive to DCPS either. Of the nearly 14,000 unfilled seats across public charter schools in SY 2021-22, an estimated 70 percent are accounted for by schools in Wards 5,7, and 8.[11]

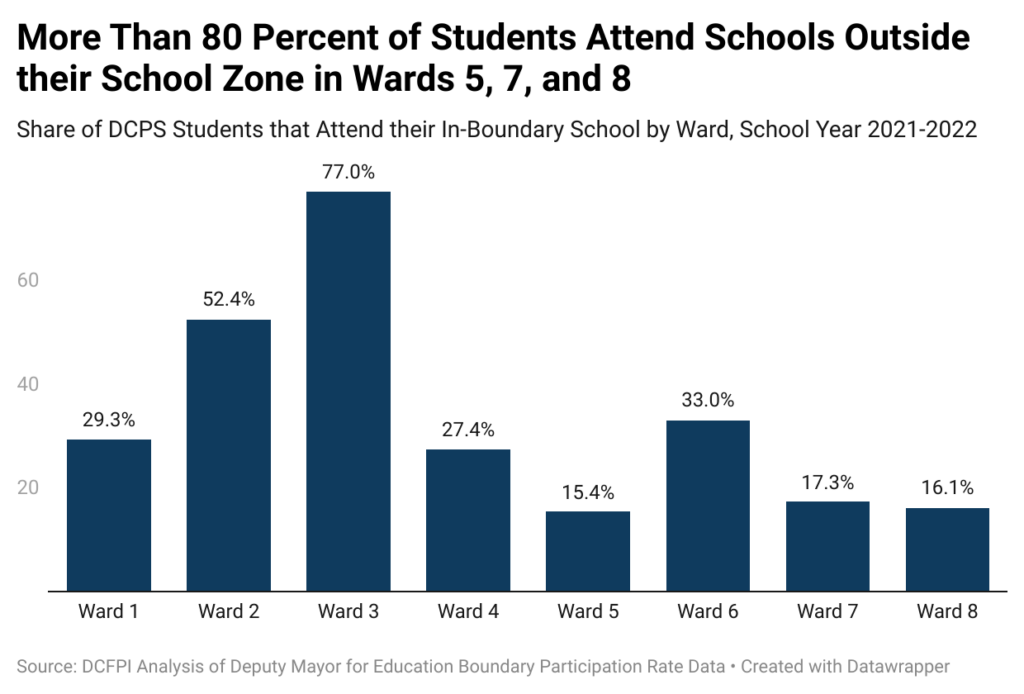

Boundary participation rates in these communities suggest that DC is failing to provide high quality, attractive schools in many parts of the District. The in-boundary participation rate of schools in Wards 5, 7, and 8 ranged between 15 and 17 percent for each ward compared to a 25 percent average for the District in SY 2021-22.[12] Comparatively, the in-boundary rate is 77 percent in Ward 3 (Chart 2).[13]

It is no coincidence that many of the neighborhoods where students are more likely to opt out of their neighborhood schools are also the areas that have been intentionally and historically neglected and segregated. Until 1948, DC expressly prohibited the sale of houses to Black residents in many neighborhoods including Columbia Heights, Mount Pleasant, Petworth, Park View and others.[14] These restrictive covenants, as well as the construction of highways such as the Anacostia Freeway, effectively displaced Black residents with lower incomes towards the far northeast and southeast parts of the city. As neighborhood DCPS schools – particularly those in Wards 7 and 8 – continue to struggle with declining enrollments, the District must be intentional in redressing the legacy of residential segregation and the myriad of ways racism formed and continues to shape school boundaries, perceptions of school quality, and enrollment patterns.

On the surface, these boundary participation rates are reflective of many parents exercising their right to choose the best school that they perceive to meet the needs of their children. DCFPI supports families’ rights to make educational choices that work best for their children, but we believe that the DME, DCPS, and the Public Charter School Board have a responsibility to articulate and enact a plan that supports both school choice and high-quality neighborhood school options and advances educational equity for all children.

Prioritize Meaningful Community Engagement within the Master Facilities Plan and Student Assignment & Boundary Zone Study

Current enrollment and migration trends severely threaten the stability of all schools in the District, but particularly neighborhood schools in historically under-resourced areas. Further, DCPS’s and the Public Charter School Board’s decisions to open and approve new citywide schools, respectively, only exacerbates instability further. The District has an opportunity to better understand & remedy these challenges through the Master Facilities Plan (MFP) and School Assignment and Boundary Zone studies. Every ten years, the Mayor is responsible for submitting an MFP detailing the capacity of existing schools, ten-year facility needs for each LEA, and recommendations for the utilization or reduction of excess space, among other requirements. Relatedly, the Mayor is also responsible for submitting a school boundary and assignment zone study to the council every ten years detailing by-right student assignment based on feeder patterns and attendance zones and if there is adequate capacity at existing DCPS schools.

These studies also present an opportunity for the DME to articulate a vision for DC’s public education system that truly supports both school choice and enrollment in neighborhood schools. The DME should be intentional about ensuring families in all areas of the city can meaningfully influence and contribute to the development and implementation of both studies. Importantly, the DME should use lessons learned from previous studies to develop intentional and equitable outreach and engagement strategies for Black and brown families, families with low incomes, and families living in Wards 5, 7, and 8.

[1] Testimony of Qubilah Huddleston, “Initial School Budgets Show DCPS Needs a Plan to Ensure Equitable Funding and Stability”, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, February 2023.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Chelsea Coffin and Julie Rubin, “Declining births and lower demand: Charting the future of public school enrollment in D.C.”, DC Policy Center, July 2022.

[4] DCFPI Analysis of DME Birthrate Data, 2016-2020.

[5] DCFPI Analysis of DME Facility Opening and Closures, School Years 2016-17 to 2021-22

[6] DCFPI Analysis of OSSE Audited Enrollment Data, School Years 2016-17 to 2021-22.

[7] DCFPI Analysis of DME Facility Utilization Data, SY 21-22.

[8] Unfilled Seats are defined as the difference between a facilities enrollment and their programmatic capacity. A school’s programmatic capacity is the maximum number of students that can be housed in each school facility given the schools’ existing educational programs, class size, and staffing.

[9] Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education, 2022 Master Facilities Plan Supplement, February 2023.

[10] DCFPI Analysis of DCPS Facility Utilization Data, SY2021-22.

[11] DCFPI Analysis of PCS Facility Utilization Data, SY2021-22.

[12] DCFPI Analysis of DME Boundary Participation Data, SY2021-22.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Meena Morar, “These maps illustrate how public housing was manipulated to segregate DC”, Greater Greater Washington, November 2019.