Corrected on April 14, 2022 to reflect the seven states that have extended the EITC to income-eligible workers who file their taxes with an ITIN—not six.

Corrected on April 14, 2022 to reflect the seven states that have extended the EITC to income-eligible workers who file their taxes with an ITIN—not six.

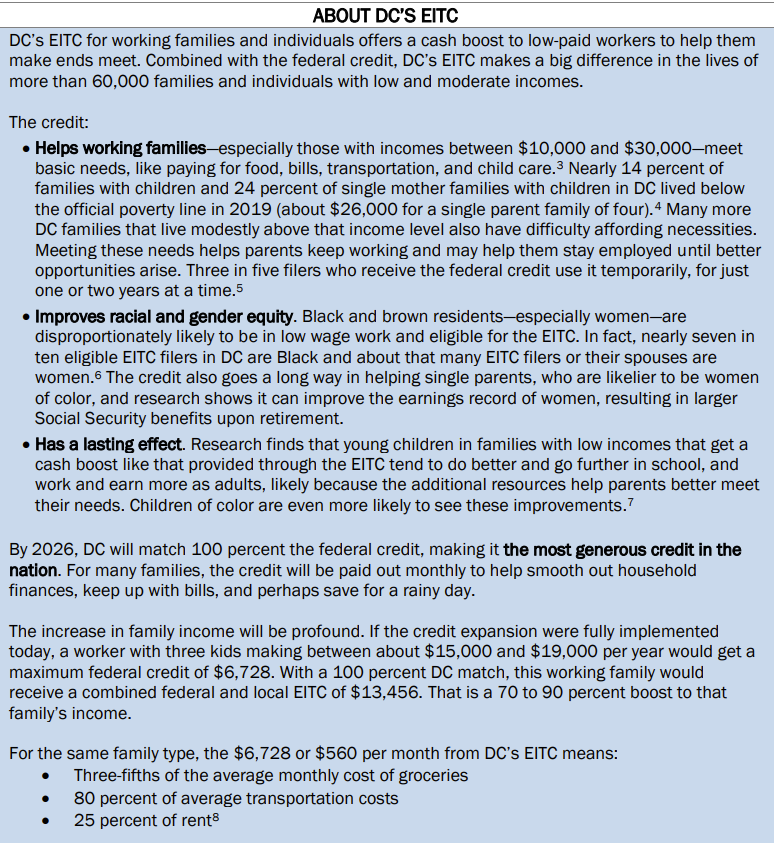

The DC Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a powerful tool for advancing racial, gender, and economic equity. Modeled after the federal tax credit by the same name, DC’s EITC goes to families and individuals earning low and moderate incomes to help them keep more of what they earn and meet basic needs.[1] It is claimed at tax time and helps people pay for expenses like rent, food, and child care. Last year, DC lawmakers expanded the credit to make it the most generous in the nation, but it is not the most inclusive. Currently, it excludes roughly more than 5,000 low-paid working households because they have at least one person who is undocumented.

Under federal rules, the EITC can only go to working households where all members (adult taxpayers and qualifying children) have a valid Social Security Number (SSN). This longstanding discrimination built into the federal credit flows through to the District’s EITC, excluding many workers and families who would otherwise be eligible based on their income. But the District can and should set its own rules.

Undocumented workers are ineligible for SSNs, but many file their taxes with an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN). DC can make this tax credit available to those filing with ITINs to ensure all workers who must make ends meet with low pay are able to make life better for their families and share in the District’s recovery and prosperity, regardless of their immigration status.[2] These workers and their families have been excluded from the credit for too long and stand to miss out even more after the major multi-year expansion to the value of the DC EITC adopted last year.

The District prides itself as a welcoming city—one that recognizes and respects the vital role that immigrants play in shaping DC’s culture, communities, and economy as friends and family, neighbors, artists, entrepreneurs, essential workers, and more—and its policies should reflect that.

DC’s EITC Should Be More Inclusive to Further Advance Racial Equity

Because of a long history of systemic racism and economic exclusion, many people struggling to make ends meet are denied access to safety net programs. For example, when Congress established a permanent unemployment insurance program during the Great Depression, it excluded farm and domestic work, leaving most Black workers ineligible.[9] Today, unemployment insurance continues to exclude many workers, including immigrants who are undocumented. The federal EITC is another program denied to people, including many workers who are undocumented, who meet income eligibility targets. They cannot claim the credit because either they or other members of their “tax unit” do not have an SSN. This is a federal level rule, and because most states rely on federal parameters and set their local EITCs as a percentage of the federal credit, this exclusion flows through to local credits.[10]

In DC, 90 percent of people who are undocumented identify as Black, Latino, or Asian.[11] People who are undocumented often face steep barriers to participating in the economy, making it harder to provide for themselves and their families. State EITCs are meant to help people and families struggling on low incomes. The income boost from the credit improves the lives of those who participate and benefits the local economy more broadly. By excluding workers because of their immigration status, DC undermines racial equity as well as the effectiveness of the program at creating a healthy, stable, thriving economy.

But DC lawmakers can choose a different path and set different rules for eligibility, and in fact precedent for this already exists. Currently, the income parameters for the District’s EITC for workers without qualifying children extends beyond those of the federal credit. DC’s so-called “childless worker” credit reaches workers earning up to about 200 percent of the federal poverty line for a single person, or about $27,000 in earnings compared with about $16,000 for the federal credit.[12] District policymakers made this change in recognition that the parameters for the federal EITC excluded too many of DC’s low-paid workers. Lawmakers can make a similar decision to extend beyond federal rules to offer undocumented workers access to DC’s EITC.

A More Inclusive EITC Would Advance a More Progressive Tax System

Expansions to DC’s EITC have advanced tax and racial justice by reducing the taxes paid by DC’s lowest income households as a share of their income. Women and people of color are disproportionately likely to work in low-paid jobs and therefore to have low incomes. The EITC is a powerful tool for countering that disparity that’s resulted from the compounding negative effects of bias, discrimination, and occupational segregation in the labor market.[13]

Expansions to DC’s EITC have advanced tax and racial justice by reducing the taxes paid by DC’s lowest income households as a share of their income. Women and people of color are disproportionately likely to work in low-paid jobs and therefore to have low incomes. The EITC is a powerful tool for countering that disparity that’s resulted from the compounding negative effects of bias, discrimination, and occupational segregation in the labor market.[13]

Workers who are undocumented, however, have not benefitted from the reduction in taxes paid as a percentage of their income made possible by DC’s expanding EITC. Their effective tax rate—total taxes paid as a share of their income—is undoubtedly higher than other similarly situated workers and their families as they pay sales and property taxes as well as fees, without the offset of the EITC.

DC’s EITC should include all income-eligible workers filing their taxes. Lawmakers can accomplish this by extending the credit to workers who file their taxes using an ITIN. (Anyone who does not have an SSN can apply to the Internal Revenue Service for an ITIN, which is used specifically for the purpose of filing income taxes.) Several states have already made this important change to their EITCs: Maine, California, Colorado, Maryland, New Mexico, Oregon, and Washington. If DC follows suit, our EITC will be among the most inclusive credits and by far the most generous.

A More Inclusive EITC Would Benefit Thousands at a Relatively Low Cost

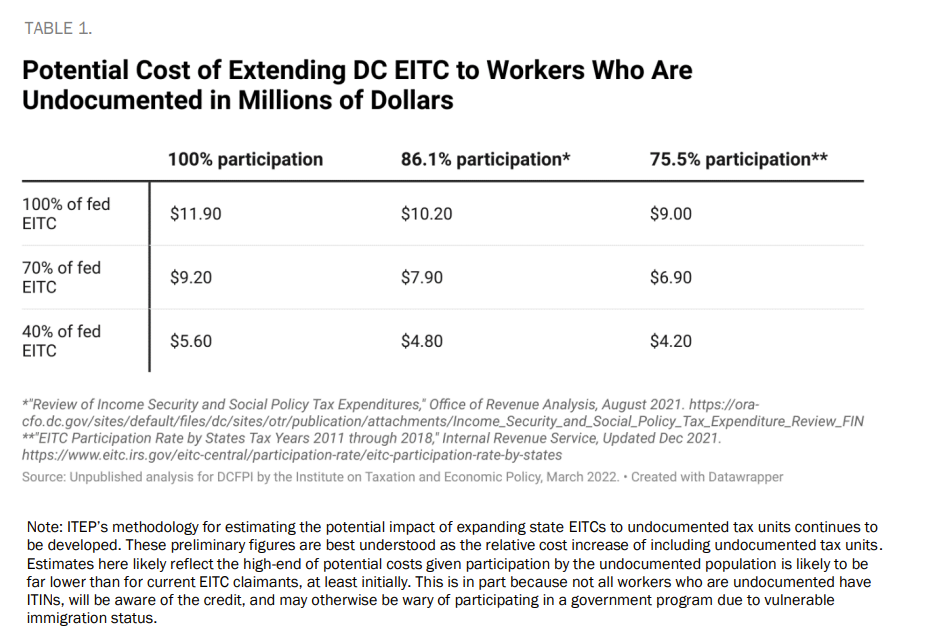

In the District, an estimated 5,100 working households with at least one member who is undocumented are income-eligible for the DC EITC but unable to claim the credit because they lack an SSN. The cost of extending the credit to this population of workers (if all were to file their taxes with an ITIN) under current benefit levels and equal to the current participation rate is roughly $4.8 million. That estimate rises to about $10.2 million once DC’s credit reaches 100 percent of the federal credit in tax year 2026 (Table 1). These are high-end estimates of the likely cost.

The Office of the Chief Financial Officer (OCFO) calculates a participation rate for DC’s EITC of about 86 percent of those eligible; the IRS estimates that DC’s participation in the federal credit is around 76 percent.[14] It is unlikely that participation among workers who are undocumented would be as high, especially as the expansion is initially implemented. The cost of state EITCs in the first year after states’ initial adoption of a credit are typically 80 to 90 percent of the cost those states would have incurred if every family claiming the federal credit also claimed the state credit.[15] It is likely that a general lack of awareness of the federal or local credit and potential fear of participating in a government program also may reduce participation among workers who are undocumented.

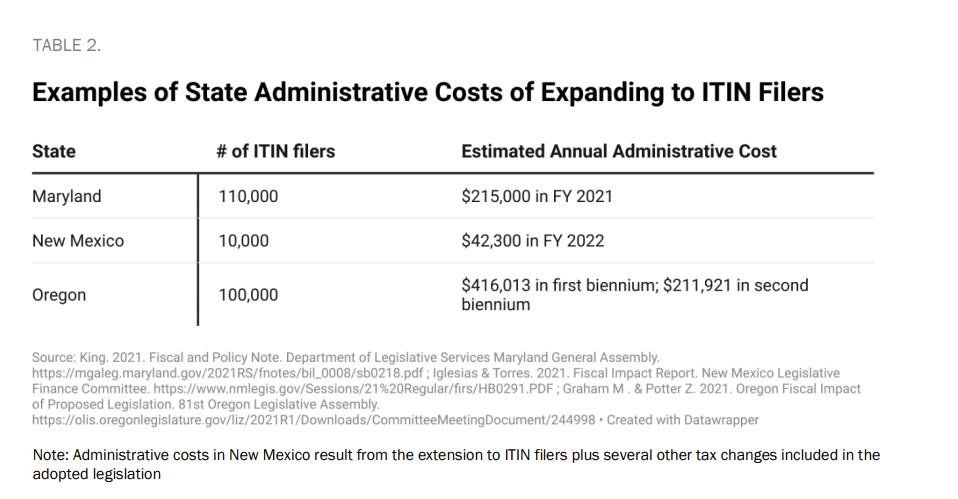

The administrative burden and cost would likely be relatively low. Among the seven states that have successfully pursued a fix to their state EITC, three (Maryland, New Mexico, and Oregon) estimated the administrative cost of delivering their credit to workers filing their taxes with an ITIN. Annual costs were highest in Maryland, with the largest state population and number of households newly eligible for the credit, followed by Oregon, and New Mexico (Table 2). The allocations cover changes to forms and instruction booklets, rulemaking, data entry, response to taxpayer inquiries, processing appeals, and the like. Given the much smaller number of ITIN filers who would be eligible for the credit in the District, and the experience the OCFO already has in delivering the credit to workers ineligible for the federal credit, the costs are likely minimal.

DC can and should offer both the most generous and one of the most inclusive EITCs in the country. The impact of the EITC on workers and families is profound, and residents who are undocumented shouldn’t be denied access to economic security because of their immigration status. We can more fully reach our economic potential in the District, advance racial and tax justice, and better create healthy, thriving communities and families, when our policies and programs are made more inclusive.

[1] Claire Zippel, September 2017, “DC’s Earned Income Tax Credit,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute.

[2] Cortney Sanders, Michael Leachman, and Erica Williams, “3 Principles for an Antiracist, Equitable State Response to COVID-19 — and a Stronger Recovery,” CBPP, Updated April 29, 2021.

[3] “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” Office of Revenue Analysis, December 2020, https://cfo.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ocfo/publication/attachments/2020%20Tax%20Expenditure%20Report_Final.pdf

[4] U.S. Census Bureau, “2019: ACS 1-Year Estimates Data Profiles,” https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=DP03&g=0400000US11&tid=ACSDP1Y2019.DP03.

[5] Timothy Dowd and John Horowitz, Long-Term Tax Liability and the Effects of Refundable Credits, Public Finance Review, September 2011; vol. 39, 5: pp. 619-652., Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2714555

[6] CBPP estimates prepared using Urban Institute’s Analysis of Transfers, Taxes, and Income Security (ATTIS) microsimulation model and American Community Survey data via IPUMS USA.

[7] Chuck Marr, et al., “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds,” CBPP, October 1, 2015.

[8] Economic Policy Institute Family Budget Calculator https://www.epi.org/resources/budget/budget-factsheets/#/326; housing costs based on the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s estimates of Fair Market Rent at the 40th percentile of DC rental costs.

[9] Ira Katznelson. When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America, W.W. Norton & Company, 2005, pg. 42-45.

[10] Samantha Waxman and Iris Hinh, “States Can Adopt or Expand Earned Income Tax Credits to Build Equitable, Inclusive Communities and Economies,” CBPP, Updated February 24, 2022.

[11] Unpublished data from the Center for Migration Studies based on Warren, Robert. “In 2019, the US Undocumented Population Continued a Decade-Long Decline and the Foreign-Born Population Neared Zero Growth.” Journal on Migration and Human Security, (March 2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/2311502421993746.

[12] Charlotte Otabor, “Brief Overview of DC EITC,” September 8, 2021https://ora-cfo.dc.gov/blog/brief-overview-dc-eitc. Note: Federal parameters for the childless worker credit expanded temporarily under the American Rescue Plan but will revert back to the previous levels mentioned here in tax year 2022.

[13] Samantha Waxman and Iris Hinh, “States Can Adopt or Expand Earned Income Tax Credits to Build Equitable, Inclusive Communities and Economies,” Updated February 24, 2022.

[14] See “Review of Income Security and Social Policy Tax Expenditures,” Office of Revenue Analysis, August 2021 and “EITC Participation Rate by States Tax Years 2011 through 2018,” Updated December 2021.

[15] Erica Williams, Samantha Waxman, and Julian Legendre, “How Much Would a State Earned Income Tax Credit Cost in Fiscal Year 2021?” CBPP, March 2020.