In this pivotal moment, DC policymakers must spend federal rescue funds in a timely way, with a laser focus on addressing the racial inequities that have excluded Black and brown communities from economic gains and left them more vulnerable to the COVID-19 crisis. Unfortunately, federal policymakers excluded certain residents—including immigrants who are undocumented and workers in the informal cash economy—from federal relief that provides vital cash assistance to those who have lost income.[1] Intentional investment is needed from DC policymakers to right this unfair exclusion and pursue an equitable and inclusive future for these workers.

A coalition of DC’s mostly Black and brown excluded workers are calling upon the DC Council to invest $200 million in cash assistance for excluded workers to help them afford basic needs such as medicine, transportation, childcare, and debt incurred throughout this pandemic. This $200 million investment is less than half of the $511 million required for 15,000 excluded workers to achieve parity with the average benefits received by workers eligible for unemployment insurance throughout the first year of the pandemic. Events DC and the DC Council dedicated $14 million in funds to community-based organizations to provide a one-time payment of $1,000 each to 13,100 workers —an important support but far short of the need. Likewise, the Mayor proposed just $15 million in support for excluded workers in her FY 2021 supplemental budget, which will not be enough to meet the needs of these workers—most of whom, when employed, are paid low wages, experience wage theft, and lack job security.

A number of states have provided robust cash assistance to excluded workers. And New York recently became the first state to provide undocumented workers with assistance similar to unemployment insurance. Under New York’s program, eligible workers whose immigration status made them ineligible for unemployment benefits can now receive $15,600 in benefits. The Council should learn from New York’s and other state models and leverage the one-time federal relief dollars to invest $200 million in cash assistance for excluded workers in DC.

Excluded Workers in DC

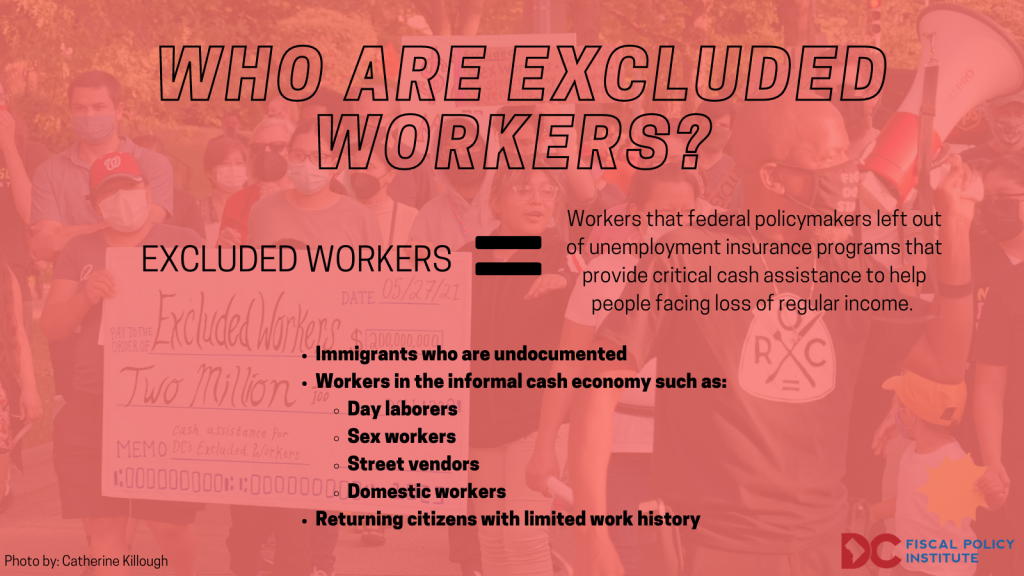

When Congress passed the Social Security Act of 1935, which established a permanent unemployment insurance program during the Great Depression, most Black workers were ineligible. This is due to the exclusion of the primary occupations that Black people held, like farm and domestic work.[2] Nearly 90 years later, unemployment insurance programs as well as other federal stimulus payments continue to exclude many workers, like immigrants who are undocumented, day laborers, sex workers, street vendors, and domestic workers, among others (Figure 1). And again, the overwhelming majority of these workers are Black and brown people.

- Workers who are undocumented: There are over 12,000 immigrants who are undocumented in DC. Roughly 54 percent originate from Latin America and another 25 percent from countries in Africa, with over 90 percent identifying as Black, Asian, or Hispanic, according to the Center for Migration Studies.[3] Prior to the pandemic, about 85 percent of workers who are undocumented were in the labor force contributing to DC’s economy and tax base.[4] In fact, workers who are undocumented contribute roughly $32 million annually in DC taxes, according to 2017 estimates from the Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy.[5]

- Returning citizens: Roughly 1,300 DC residents are returning citizens released from the carceral system last year, according to the Council for Court Excellence. [6], [7] Most of these returning citizens are Black men. Returning citizens are typically excluded from federal unemployment insurance due to their lack of work history but the DC CARES Program is inclusive of people released after March 11, 2020.

- Sex workers: There are roughly 100 sex workers in DC, according to HIPS, a community organization working to promote the health, rights, and dignity of individuals and communities impacted by sexual exchange and/or drug use due to choice, coercion, or circumstance.[8]

- Additional workers in the cash economy: Data on the number of day laborers, street vendors, and domestic workers are unavailable. There may be overlap with the above-mentioned groups, however immigrants who are documented and returning citizens from past years, continue to have higher levels of unemployment in the formal economy and may work informally.

Due to a long history of structural racism, discrimination, and economic exploitation, the vast majority of DC’s excluded workers are Black and brown people who earn or have earned low wages and are more likely to work in sectors hit hardest by this recession. [9] DC’s hardest hit industry during the pandemic has been leisure and hospitality, where employment is still down by 48 percent or nearly 40,000 jobs, and occupational segregation within that industry has exposed Black and brown workers, and women of color, to the worst job losses.[10], [11] Research has shown that Black and brown workers face longer rates of unemployment both during the peak of recessions and throughout economic recovery. In DC, Black workers still had not fully recovered from the Great Recession in 2018, ten years after its peak.[12] It is highly likely, therefore, that Black and brown workers, including those excluded from unemployment and other forms of assistance, will continue to face economic hardship long after the city begins to recover from the pandemic because of ongoing labor market discrimination. If DC policymakers fail to provide this much-needed lifeline, excluded workers and their families will fall even further behind.

Excluded Workers’ Demand for Inclusion is Far Below Actual Need

The District and Events DC stepped up and approved two rounds of cash grants to help excluded workers pay for basic needs. The DC CARES program started with $5 million from the Events DC budget which served undocumented workers and $9 million in FY 2021 for a broader range of excluded workers, which continued to be administered using the DC CARES program.[13] The program is designed to foster a low-barrier, community-engaged approach to administration. Events DC sends funding to the Greater Washington Community Foundation which then both purchases debit cards for recipients and regrants funding to seven community organizations to disburse the cards and run the program.[14] The community organizations reach out to additional organizations that work directly with excluded workers to ensure the program reaches as many eligible people as possible.[15] All program funds will be committed by the end of this July 2021, reaching 13,100 workers.[16]

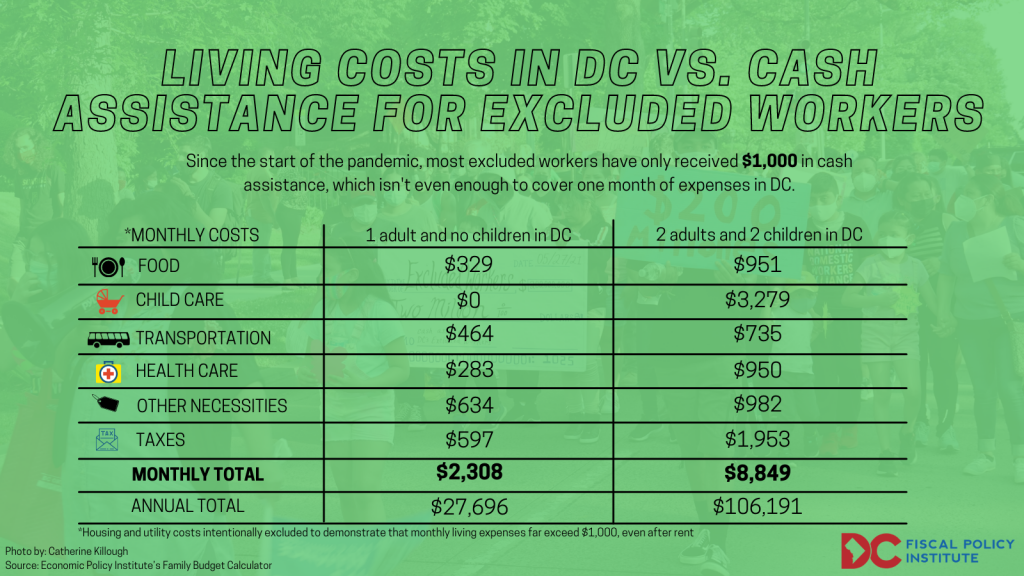

Despite the success of the program, a one-time payment of $1,000 per person is not enough to meet ongoing needs during this prolonged crisis. Monthly costs of living in DC far exceed that amount, even when excluding housing costs. Not including rent and utilities, a single adult with no children in DC needs roughly $2,308 per month to cover the costs of food, transportation, and other needs. Two adults and two children need $8,849 per month to cover these costs plus child care, according to the Economic Policy Institute’s Family Budget Calculator (Figure 2)[17] Hardship in the region is particularly high due to the pandemic, according to a recent survey by the Capital Area Food Bank. The survey found that over 50 percent of newly food insecure respondents identified as Hispanic, and that Hispanic respondents reported higher rates of job loss and reduced work hours than before the pandemic.[18]

Excluded workers have called on the Mayor and DC Council to allocate $200 million to DC CARES to support basic needs such as medicine, transportation, childcare, and debt that they have incurred throughout this pandemic. This $200 million allocation would pay for:

- $12,000 in cash assistance per person—equivalent to $1,000 per month for the first year of the pandemic. Includes:

- $157 million in checks to applicants who are currently approved in DC CARES(approximately 13,100 people);

- $23 million for new applicants, approximately 1,900 more people

- Up to 10 percent for program administration ($20 million). This is a maximum as the program will likely use much less in overhead. Remaining funds can be used to cover program outreach for new applicants, provide technical assistance, or serve additional residents.[19]

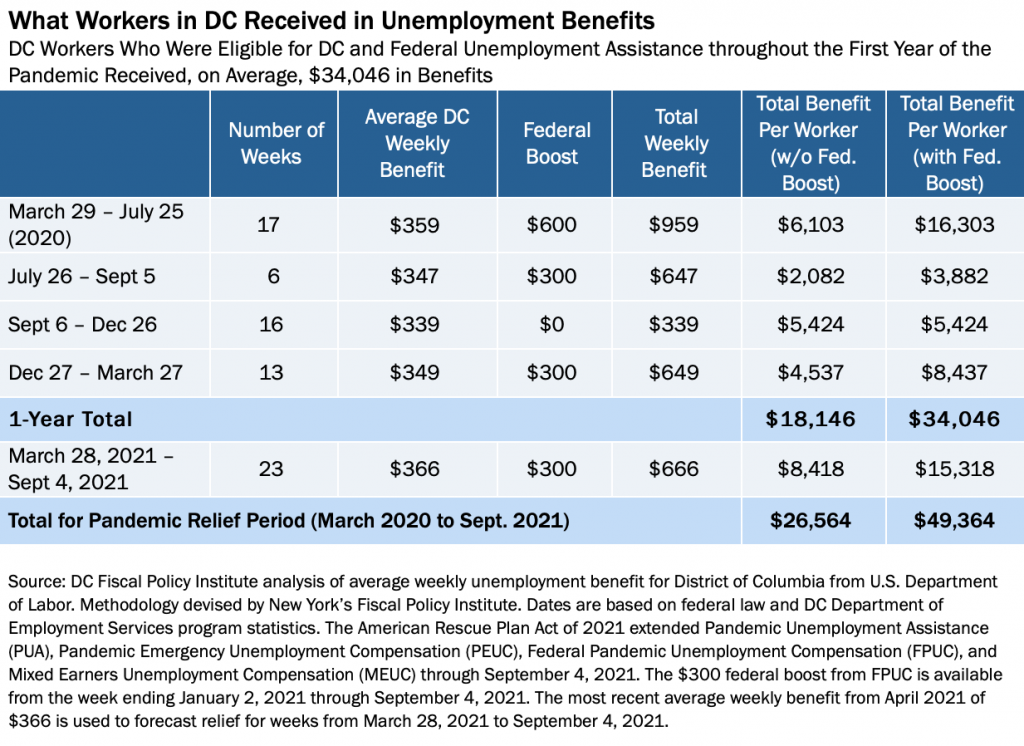

This demand is still substantially less than the roughly $34,046 that unemployed workers who were eligible for unemployment insurance received, on average, over the past year (Figure 3). Fully achieving parity for the 13,100 current DC CARES recipients and 1,900 new recipients for the first year of the pandemic would require a total investment of $511 million.

An Investment of $200 million Will Allow Families to Get Out of Debt and Pay for Basic Needs

“The pandemic has been super difficult. I didn’t receive a single cent from the government. I didn’t receive any kind of help except for the support from Ward 2 Mutual Aid. Everyday that passes we live in fear that we’ll lose our home again and be left on the streets. Those of us who don’t have papers are doing everything possible just to survive. We deserve to recover from this pandemic like everyone else… We also deserve to recover from these terrible times with dignity and respect. That is why we need $200 million for all the workers like me who need aid.”

-Noemi, an excluded worker

A $200 million investment in excluded workers would allow them to meet their families’ needs, pay down debt, and otherwise build some semblance of security. Flexible cash assistance has been shown to provide stability for individuals and children, reduce stress, and avert extreme hardship.[20] From December 2020 to April 2021, flexible cash assistance from the federal government to U.S. households corresponded with major declines in food insufficiency, financial instability, and adverse mental health symptoms, according to researchers from the University of Michigan.[21], [22] Results from two guaranteed income pilot programs demonstrate that unrestricted cash provides Black women and mothers safety, security, and choice for themselves and their families—all of which amount to a form of care for Black women, according to the Economic Security Project. Providing that assistance defies the “strong Black woman” trope that simultaneously demands strength, caregiving, and resiliency from Black women while denying their need for care and support.[23]

Several States are Providing Relief to Excluded Workers and Providing Assistance that is Roughly on Par with Unemployment Insurance

The U.S. Department of the Treasury (USDT) encourages states to use federal relief from the American Rescue Plan to address negative economic impacts caused by the public health emergency, including economic harms to workers and households, and to serve the hardest-hit communities and families.[24] An analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities further demonstrates that the American Rescue Plan and USDT do not require government entities nor grantees to ask about immigration status when deploying recovery funds, meaning funds can be used by DC policymakers for all excluded workers.[25]

With nearly $2.3 billion in flexible federal funds, DC policymakers have a historic opportunity to repair the damage done by the COVID-19 crisis, especially for DC’s excluded workers who have received very minimal assistance.[26] The District should follow the lead of other states—such as Washington, Oregon, and Colorado—that have funded cash assistance for excluded workers with a mix of federal and state funds.[27] While the $200 million called for by excluded workers is a one-time payment, DC could go further in the future. New York recently became the first state to provide cash assistance to undocumented workers that is akin to unemployment insurance—with some workers receiving $15,600.[28]

The Mayor and the Council should dismantle exclusionary structures and policies that have left thousands of DC’s workers vulnerable in this crisis. They can invest now to begin undoing deeply entrenched patterns of exclusion and disproportionate harms to Black and brown people, immigrants, and people working in the cash economy by rejecting a return to normal. It will take intentional investments and interventions to reverse course and pursue an equitable future for excluded workers.

[1] Our analysis focuses on workers left out of federal and DC unemployment insurance programs due to their immigration status, lack of work history, or work in the informal cash economy. Throughout this brief, we compare the average unemployment benefits received by eligible workers in DC with the amount that DC awarded excluded workers through the DC CARES program. Federal stimulus payments are not the focus of this analysis as eligibility shifted over time with different federal relief bills. The second phase of the DC CARES program includes a number of requirements for participants including that they be ineligible for unemployment insurance or COVID-19 related federal relief, or be a recent returning citizen.

[2] Ira Katznelson. When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America, W.W. Norton & Company, 2005, pg. 42-45.

[3] Warren, Robert. “In 2019, the US Undocumented Population Continued a Decade-Long Decline and the Foreign-Born Population Neared Zero Growth.” Journal on Migration and Human Security, (March 2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/2311502421993746.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Lisa Christensen Gee, Matthew Gardner, Misha E. Hill, and Meg Wiehe, Undocumented Immigrants’ State & Local Tax Contributions, Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy, Updated March 2017.

[6] Council for Court Excellence and Public Welfare Foundation, D.C.’s Justice Systems Overview 2020, May 11, 2021.

[7] The Bureau of Prisons released 1,040 people convicted of DC Code offenses between January and August 2020, according to BOP data received by Council for Court Excellence on June 24, 2021.

[8] Data on the number of sex workers in DC are sparse.

[9] Doni Crawford and Kamolika Das, Black Workers Matter: How the District’s History of Exploitation & Discrimination Continues to Harm Black Workers, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, January 28, 2020.

[10] Economic Policy Institute analysis of data from Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics, April 2021

[11] Elise Gould and Melat Kassa, Low-wage, low-hours workers were hit hardest in the COVID-19 recession: The State of Working America 2020 employment report, Economic Policy Institute, May 20, 2021.

[12] Doni Crawford and Kamolika Das, Black Workers Matter: How the District’s History of Exploitation & Discrimination Continues to Harm Black Workers, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, January 28, 2020.

[13] Kate Coventry, Qubilah Huddleston, and Alyssa Noth, What’s In the Approved FY 2021 Budget for the Safety Net?, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, September 21, 2020.

[14] The DC CARES program is administered by: Bread for the City, CARECEN, Centronia, Far Southeast Family Strengthening Collaborative, Latin American Youth Center, and Mary’s Center. DC Jobs with Justice has a convening, coordinating role and is also a grantee of this program.

[15] These organizations include: Council for Court Excellence, National Association Advancement of Returning Citizens, National Reentry Network for Returning Citizens, Many Languages One Voice, HIPS, and Friends and Family of Incarcerated People.

[16] Some 2,500 workers, or about half of workers who received assistance in the first round of cash grants applied for assistance in the second round, but were ineligible due to the one-time nature of the program. This demonstrates the need for more than a one-time payment of $1,000 for excluded workers.

[17] Economic Policy Institute, Family Budget Calculator, March 2018.

[18] Capital Area Food Bank, 2021 Hunger Report: Insights on Food Insecurity, Inequity, and Economic Opportunity in the Greater Washington Region, 2021.

[19] Through outreach, the program could also provide technical assistance for potential recipients to learn how cash (either as a large lump sum or recurring payments) might affect their other benefits.

[20] Tazra Mitchell, TANF at 22: Cash Income Is Vital to Families Living on the Edge, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 20, 2018.

[21] Patrick Cooney and H. Luke Shaefer, Material Hardship and Mental Health Following the COVID-19 Relief Bill and American Rescue Plan Act, Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan, May 2021.

[22] Jason DeParle, Stimulus Checks Substantially Reduced Hardship, Study Shows, The New York Times, June 2, 2021.

[23] Ebony Childs and Madeline Neighly, In Celebration of Black Moms: Cash as Care, Economic Security Project, April 29, 2021.

[24] U.S. Department of Treasury, Fact Sheet: The Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Will Deliver $350 Billion for State, Local, Territorial, and Tribal Governments to Respond to the COVID-19 Emergency and Bring Back Jobs, May 10, 2021.

[25] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Memo on Treasury’s Interim Final Rule for the Rescue Plan’s Fiscal Recovery Funds, May 12, 2021.

[26] Erica Williams, Five Ways the Mayor’s Budget Can Advance an Antiracist, Equitable Future, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, May 26, 2021.

[27] Nina Shapiro, Washington Legislature approves $340M for COVID-19 Immigrant Relief Fund, making it one of the country’s largest, The Seattle Times, April 29, 2021.

[28] David Dyssegaard Kallick, Brief Look: Excluded Worker Fund: Aid to Undocumented Workers, Economic Boost Across New York State, Fiscal Policy Institute, April 7, 2021.