Chairman and members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today. My name is Kate Coventry, and I am a senior policy analyst at the DC Fiscal Policy Institute. DCFPI is a nonprofit organization that promotes budget choices to address DC’s economic and racial inequities and to build widespread prosperity in the District of Columbia, through independent research and policy recommendations.

I would like to focus my testimony on the need for services for residents with low-incomes with traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), also known as acquired brain injuries (ABIs), and the need to simplify the DC Healthcare Alliance recertification process.

The fiscal year (FY) 2021 budget includes $698,000 to allow some behavioral health outpatient providers to offer enhanced services for TBIs as well as autism spectrum disorders. This is a great new public investment, but more is needed to ensure that Department of Behavioral Health-certified provider organizations are able to provide these services to a larger number of residents in need. DCFPI asks the Department of Health Care Finance to work with the Department of Behavioral Heath to include these services in the upcoming rate study and make any necessary rulemaking.

The FY 2021 proposed budget also includes funding to allow Alliance recipients to renew their insurance by phone twice per year rather than in person. This is a good step towards simplifying the Alliance recertification process, but the Council should add additional funding to allow Alliance recipients to renew online annually, just like Medicaid recipients do.

TBIs Have Significant Negative Effects

TBIs are injuries resulting from a blow or jolt to the head, or a penetrating injury to the head, that disrupts the function of the brain.[1] TBI in adults is associated with an increased risk for substance misuse, major depression, anxiety, and unemployment.[2]

TBIs can negatively affect self-regulation and executive functioning. Self-regulation refers to a person’s ability to manage behavior associated with stress and anxiety. For a person with TBI, this might entail difficulty waiting or taking turns; difficulty calming down; or feeling overwhelmed in new places. Executive functioning refers to higher-order brain functions associated with setting goals, organizing, remembering, following directions, and focusing attention. People with TBIs can become easily confused or forgetful; have difficulty learning new information; filling out forms; and using public transportation. Some have difficulty problem-solving, and others have problems with judgment and decision-making. After experiencing a TBI, people may have trouble keeping track of time, making plans, making sure to complete plans or assignments, applying previously learned information to solve problems, analyzing ideas, and looking for help or more information when needed.

Vulnerable Populations Are Particularly at Risk

People who are homeless are at high risk of acquiring a TBI: 50 to 80 percent of them have sustained at least one brain injury prior to homelessness, national statistics show.[3] The DC rate is elevated as well. In 2010, 199 DC homeless individuals were surveyed and nearly two-thirds had a TBI.[4] TBI may be a risk factor for becoming homeless, research shows.[5] Homeless individuals are also at a higher risk of acquiring a TBI because they are more likely to be victimized by assault, experience trauma, and have substance use disorders that can cause falls.[6]

A 2016 survey of 159 adult DC behavioral health clients found that approximately 50 percent had a history of TBI.[7]Additionally, active-duty military personnel are at very high risk. Domestic violence survivors are also at high risk because “the head and face are among the most common targets of intimate assaults.”[8] And finally, TBI is a common co-occurring disorder among people who are diagnosed with a major mental illness and who have a history of substance misuse and criminal justice involvement.

DC Residents with TBIs Are Not Getting the Services They Need, with Devastating Implications

Right now, DC behavioral health providers generally do not screen, identify, or treat the symptoms of TBI because TBI is not an official billable diagnosis in DC’s behavioral health system, and there is no system to train mental health providers. Community-based providers cannot receive payment for services provided to treat TBI, whether it is a standalone diagnosis or co-occurring disorder. This results in DC residents with TBIs not getting the care that they need. The new investment of $698,000 to allow some outpatient providers to offer enhanced services for both TBIs as well as autism spectrum disorders is a great first step, but more funding is needed to reach all residents in need.

The lack of services has terrible implications for individuals with TBI. Research has found that people with cognitive impairments like TBI may be falsely considered non-compliant and then get expelled from programs because these impairments prevent them from fully participating in the services. Or, sometimes they are banned from sites because of “disruptive behavior or failure to comply with prescribed treatments.”8 To the untrained eye, problems with executive functioning can look like lack of motivation, laziness, disregard for others, and a reluctance to engage in social activities. Given that a 2010 survey of 12 DC homeless service providers found that only one provider had received any training on TBIs, it is likely that many homeless individuals with TBI are being excluded from mainstream homeless services.[9]

The Department of Health Care Finance should work with the Department of Behavioral Health to include these services in the upcoming rate study that will look at the health care costs associated with covered benefits in the effort to adjust payment rates to providers. We also ask DBH to work with Department of Health Care Finance to make any rulemaking needed to implement TBI services.

The District Should Ensure DC Alliance Recertification Are as Easy as Possible

The DC Healthcare Alliance should have low-barrier application and recertification requirements. This program provides critical health care coverage to residents with low incomes who do not qualify for Medicaid, most of whom are immigrants. The District should be doing all it can to ensure that as many residents as possible have access to insurance and that access is as easy as possible.

Given their shared purpose, the DC Healthcare Alliance and Medicaid program should have identical, low-barrier application and recertification requirements. But the DC Healthcare Alliance requires participants to recertify every 6 months and normally does not allow participants to do this online, while Medicaid only requires annual recertification and allows participants to do so online.

The FY 2021 proposed budget takes positive steps by allowing Alliance recipients to renew their insurance by phone twice per year rather than in person. This is a good step towards simplifying the Alliance recertification process but the Council should add additional funding to allow Alliance recipients to renew online annually, just like Medicaid recipients do.

We should not erect higher barriers just because a resident is undocumented or very low income—DC is a welcoming city, and our policies should reflect that value. The District waived the in-person interview requirement for the Alliance during the public health emergency. DC needs to make this improvement permanent and move to annual, virtual recertification to reflect our DC values.

Shortened Eligibility Period Has Led to Turnover, Poorer Health, and Higher Costs

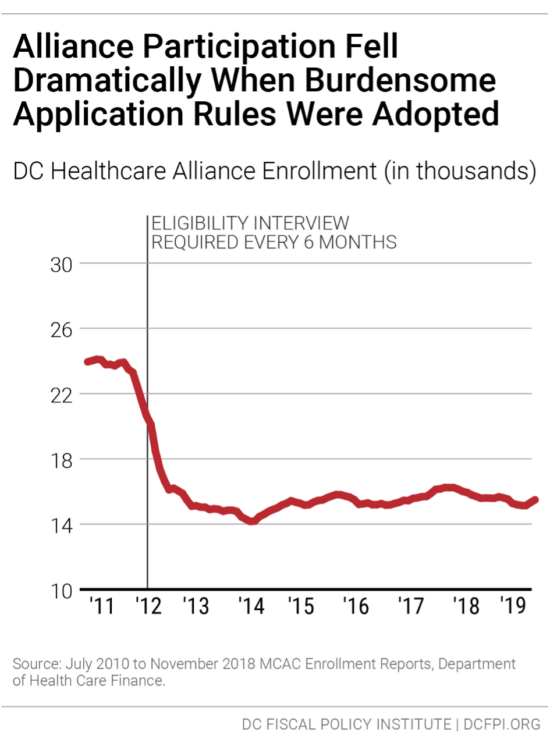

In 2011, DC implemented restrictive procedures to maintain Alliance eligibility that immediately led to a sharp drop in participation (Figure 1). Thousands of residents who should have health insurance have not, and the uninsured rate is much higher among Latinx DC residents[10] than others.

The restrictive rules also contribute to a high rate of turnover in the Alliance, as residents join the program but then drop off due to the time-intensive requirements. Only 55 percent of Alliance participants renew their eligibility when it comes up, data from the District’s Department of Health Care Finance show.[11] Given that many Alliance members are working at jobs without paid leave and that visiting a Department of Human Services center can take an entire day or longer, it is not surprising that many are not able to renew their benefits.

This lack of continuous coverage contributes to poor health outcomes and high costs per person in the Alliance. Churn from frequent recertification increases health program costs because it limits access to preventive care, which means participants often are sicker when they re-enroll, and because sicker residents are most willing to go through the process of maintaining coverage. Healthcare Alliance costs have doubled in the past four years, even though participation has not grown. The cost increases appear to reflect other factors, including a growing number of older participants.[12]

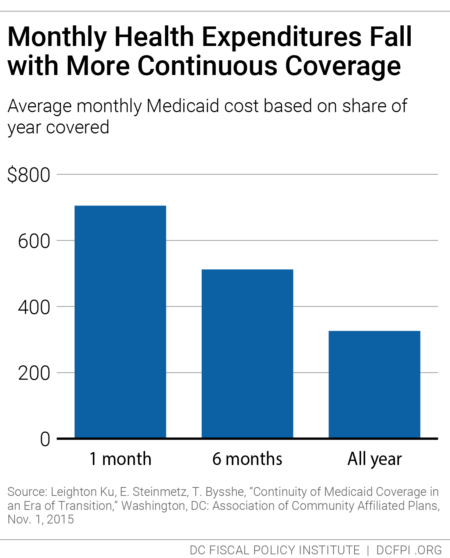

Research from Medicaid, for example, shows that average health care costs go down the longer participants have coverage (Figure 2). DCFPI recommends the agency look at recipients who normally would have cycled off the Alliance but did not because of the waiver of the recertification requirement during the public health crisis to see how the longer coverage affected their health and health care costs.

DC has been a leader in expanding health insurance coverage to improve resident health and reduce health disparities. The Council should eliminate barriers to care is a critical component of those important city goals and would go a long way towards affirming support for our immigrant neighbors.

Thank you, and I am happy to answer any questions.

[1] “Traumatic Brain Injury & Concussion,” Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

[2] Suzanne Polinder, Juanita A. Haagsma, David van Klaveren, Ewout W. Steyerberg, and Ed F van Beeck, “Health-Related Quality of Life after TBI: A Systematic Review of Study Design, Instruments, Measurement Properties, and Outcome,” Population Health Metrics, February 17, 2015.

[3] Jennifer L. Highley and Brenda J. Proffit, “Traumatic Brain Injury Among Homeless Persons: Etiology, prevalence, and severity, Health Care for the Homeless Clinicians’ Network,” revised June 2008

[4] “Findings from the District of Columbia Traumatic Brain Injury Needs and Resources Assessment of Homeless Adult Individuals, Homeless Shelter Providers, TBI Survivors and Family Focus Group, TBI Service Agency/Organizations,” DC Department of Health, revised August 2010.

[5] Jane Topolovec-Vranic, Naomi Ennis, Angela Colantonio, Michael D. Cusimano, Stephen W. Hwang, Pia Kontos, Donna Oucherlony, and Vicky Stergiopoulos, “Traumatic brain injury among people who are homeless: a systematic review,” BMC Public Health, 2012.

[6] “Findings from the District of Columbia Traumatic Brain Injury Needs and Resources Assessment”

[7] Amy Burkowski, David Freeman, Faiza Majeed, Jennifer “Niki” Novak, Paul Rubenstein, and Celeste Valente, “Traumatic Brain Injury in the District: The Ignored Injury: A Paper Examining the Prevalence of TBI in the District and the Need for Services,” revised July 2018.

[8] “Findings from the District of Columbia Traumatic Brain Injury Needs and Resources Assessmen.t”

[9] Ibid.

[10] Jodi Kwarciany, “DC Has Disparities in Health Coverage Despite Its Low Uninsured Rate,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, revised September 25, 2017.

[11] Ed Lazere, “No Way to Run a Healthcare Program: DC’s Access Barriers for Immigrants Contribute to Poor Outcomes and Higher Costs,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, revised March 17, 2019, https://www.dcfpi.org/all/no-way-to-run-a-healthcare-program-dcs-access-barriers-for-immigrants-contribute-to-poor-outcomes-and-higher-costs/

[12] Ed Lazere (2019).