The richest 1 percent of DC residents pay less in DC taxes as a share of their income than middle-income residents, according to new findings from a leading tax research organization, and the richest 20 percent pay less than the bottom 80 percent of residents combined.[1] The new analysis also shows that DC’s flawed tax system fails to adequately lessen DC’s gaping racial income inequities. The vast majority of high-income residents are white, a result of centuries of institutionalized racism, but our tax system does not require more of high-income white DC residents than a proportionate share of DC’s taxes.

As we witness an ongoing pandemic that has widened DC’s long-standing economic and racial inequities, and as we struggle to find the resources to address the pandemic’s harm, the place for lawmakers to start is to increase taxes on the wealthiest DC residents and righting DC’s upside-down tax system.[2]

DC’s Tax System Favors the Top One Percent

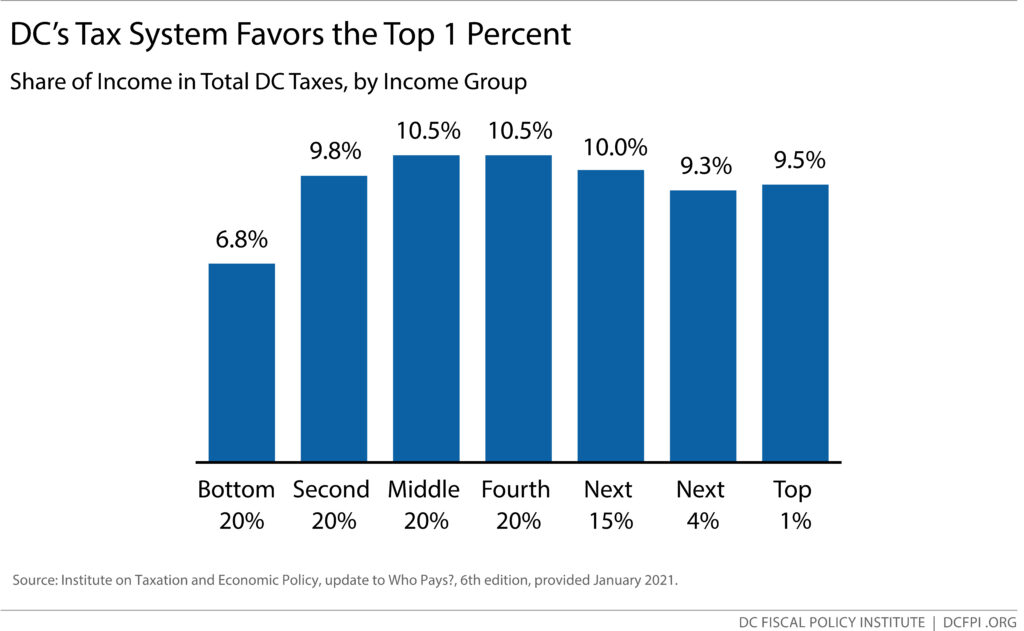

A tax system that adequately advances racial and economic justice must be progressive, requiring the richest people to pay a much higher share of their income in taxes than lower-income families who have little or no wiggle room in their family budget. Yet new findings from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), a national nonprofit research group with a sophisticated tax model, show that DC’s richest residents pay a smaller share of their income in taxes, or a tax responsibility level, than most other residents:[3]

- The richest 1 percent—those with incomes above $919,000—pay 9.5 percent of their income in DC income, sales, and property taxes. That is a lower level of tax responsibility than that paid by middle-income residents—10.5 percent—and lower than or close to the tax responsibility for all other income groups except the bottom 20 percent, those with incomes below $24,000 (Figure 1).

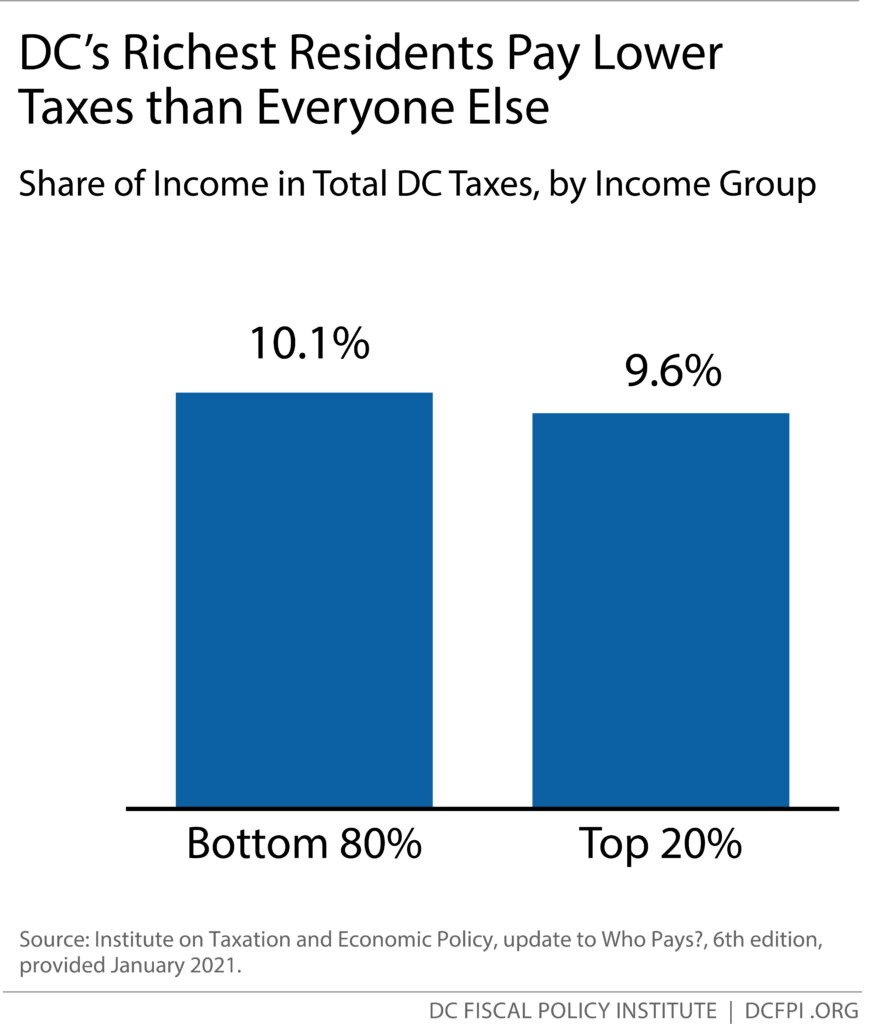

Figure 1 - The average level of tax responsibility for the richest 20 percent of households is 9.6 percent, compared with 10.1 percent average for the bottom 80 percent of households (Figure 2).

DC’s Income Tax is Not Progressive Enough to Offset the Impacts of Sales and Property Taxes on Residents with Low or Moderate Incomes

The richest in DC pay a lower share of their income in taxes than others because two of our main revenue sources—sales and property taxes—fall hardest on low- and moderate-income residents. Sales and excise taxes especially affect lower-income families, since most live paycheck to paycheck and must spend most of their earnings to get by. Meanwhile, higher-income families can afford to save and therefore spend a relatively small share or their income on taxable goods and services. As a result, sales taxes—which cover things like utilities, clothing and phone bills—amount to a higher share of income for a cashier than a law firm attorney.

Property taxes affect lower-income residents, even if they rent their homes, since landlords pass on the costs of property taxes to their renters as part of monthly rent payments.[4] ITEP finds that DC’s lowest-income residents pay a larger share of their income in property taxes than higher-income families.[5] This is true in part because DC’s rising rents mean that property taxes paid by renters have risen substantially. For homeowners, however, DC’s property tax includes provisions to limit taxes in ways that widen tax inequities, including a 10 percent cap on annual increases in a home’s taxable assessment. This provision limits taxes the most for homeowners most in areas where home values are rising fastest.

The only tax that asks more of higher-income residents is DC’s income tax, but even DC’s income tax is not especially progressive. DC’s top income tax rate—8.95 percent on taxable income above $1 million—is barely above the marginal tax rate on added earnings paid by middle-income workers such as nurses or teachers—8.5 percent. This means that in a city struggling to address vast inequities, a nurse or teacher pays almost the same income tax rate on added earnings as a multi-millionaire CEO. Meanwhile, DC’s richest residents have benefitted from hundreds of millions in federal tax cuts passed in 2017.[6]

When DC’s not-very-progressive income tax is combined with sales and property taxes that fall hardest on middle and lower-income families, middle-income families still pay more of their income in taxes than the richest fellow residents.

Despite these findings, ITEP ranks DC’s tax system as one of the more progressive. That partly reflects that many states have even more flawed tax systems, and it also reflects a bright spot in DC’s tax system—the fact that DC’s taxes are relatively low for families with very low incomes. The poorest 20 percent of DC households pay less of their income in state and local taxes than in all but two states,[7] thanks to substantial tax benefits for lower-income families, such as a large Earned Income Tax Credit. Beyond our lowest-income families, however, ITEP shows that our tax system is not progressive at all.

Taxing the Wealthy in DC is a Matter of Racial Justice

Systemic racism has kept Black and brown DC residents in lower-paying jobs, with fewer educational opportunities, limited access to wealth building, and more.[8] Yet these new tax findings show that the District is not using the tax code to meaningfully lessen its vast income and wealth inequalities created by systemic racism. The average income of white households is 2.11 times higher than the average Black household income in DC before taxes are considered, according to ITEP, and 2.08 times higher when taxes are taken into account. A truly progressive tax system would hold higher-income households accountable for paying a much larger share of taxes than their share of income. However, the share of all DC taxes paid by the richest white residents—42 percent—is basically the same as their share of overall DC income, which is 41.5 percent.[9]

The Mayor and Council should use this moment to reduce inequities in DC by improving a tax system that has been used for too long to protect our wealthiest residents. DC’s flawed tax system—where the richest, predominantly white residents pay less than the middle class—is holding us back from making long-term investments needed for racial justice. A tax increase on the wealthiest would barely affect their well-being, since they spend only a fraction of what they earn. In fact, a tax increase on individuals with taxable income of more than $250,000 would affect just 3 percent of taxpayers in the District,[10] and for the wealthiest taxpayers, the tax increase would take up just a fraction of their recent increase in wealth.

Increasing taxes on the wealthiest DC residents and businesses would help offset the rising income and wealth inequality in DC, and provide resources needed to finally tackle some of DC’s deepest inequities—in education and housing in particular. It would help us come out of the pandemic as strong as possible by pouring money into lower-income families and their families, supporting landlords, small businesses, grocery stores, and more.

[1] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, update to Who Pays?, 6th edition, provided January 2021. The unit of analysis for this research paper is “tax units,” but for accessibility purposes, the author uses “residents” and “households” as proxies.

[2] Danielle Hamer, “The District Must Enact Revenue Options to Thwart Deeping Income Inequality,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, December 15, 2020.

[3] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 2021.

[4] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, How Property Taxes Work, August 2011.

[5] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 2021.

[6] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “TCJA by the Numbers, 2020” August 29, 2019.

[7] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 2021.

[8] Doni Crawford and Kamolika Das, “Black Workers Matter: How the District’s History of Exploitation & Discrimination Continues to Harm Black Workers,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, January 28, 2020.

[9] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 2021.

[10] Special data request to Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 2020.