Chairperson Nadeau and members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today. My name is Kate Coventry and I am a senior policy analyst at the DC Fiscal Policy Institute. DCFPI is a nonprofit organization that promotes budget choices to reduce economic and racial inequality and build widespread prosperity in the District of Columbia through independent research and thoughtful policy recommendations.

I am here today to testify on:

- the positive steps the Department of Human Services (DHS) has taken to protect vulnerable residents during COVID-19;

- how the Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) should be changed to ensure it prevents evictions;

- how the Interim Disability Assistance (IDA) program should be expanded to reach more in need; and,

- how the District should fund the legislation that reduces barriers to DC Healthcare Alliance enrollment and recertification.

DHS Taken a Number of Positive Steps to Protect Vulnerable Residents During COVID-19

DHS has faced an unprecedented situation with the COVID-19 crisis and has taken a number of steps that have protected clients and ensured access to critically needed benefits including:

- Waiving recertification and in-person interview requirements for medical insurance, food, and cash benefits whenever allowed by the federal government;

- Quickly implementing pandemic EBT food benefits that are intended to replace school meals while schools were closed last school year;

- Offering three meals per day, improving case management options, and allowing 24-hour access at shelter sites so individuals can practice social distancing and do not need to leave the shelter;

- Partnering with Unity Health on the PEP-V These are hotel rooms for individuals experiencing homelessness thought to be at the greatest risk for severe complications and/or death if they contract COVID-19;

- Working to ensure as many DHS clients as possible received stimulus checks by providing help directly to clients as well as guidance to providers; and,

- Begun vaccine rollout in shelters and PEP-V sites and launched peer program to help answer questions and address concerns.

We applaud DHS for taking these proactive steps that have helped keep residents alive and provided them financial security and less stress.

The District Should Ensure that ERAP Prevents Evictions

DC’s ERAP program helps residents avoid eviction by paying for overdue rent and related legal costs. Despite the Council passing emergency legislation waiving limitations on the number of months of rental arrears that ERAP can pay, the Department of Human Services (DHS) has decided to limit assistance to 5 months. This is not going to be sufficient for most renters to avoid eviction as the economic downturn started 11 months ago and will likely continue for additional months. DHS should increase or the Council should pass new legislation requiring DHS to provide more assistance so that ERAP actually prevents evictions.

Interim Disability Assistance Not Reaching All Who Need It

Interim Disability Assistance (IDA) serves as a vital lifeline for DC residents with disabilities who cannot work and have no other income or other means to support themselves. It provides modest, temporary cash benefits to adults who have applied for federal disability benefits (Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)) and are awaiting an eligibility determination. The wait time for federal benefit determination has skyrocketed in recent years, from 350 days in 2012 to nearly 600 days in 2017, leaving residents too sick to work but lacking benefits.[1]

IDA allows recipients to pay for basic needs such as transportation, medicine, toiletries, and food. In addition, the steady modest monthly income allows recipients to access some housing programs that are administered by nonprofit organizations and require residents to have some kind of income.

IDA is paid for with a combination of local funding, reimbursement from the federal government, and funds from the SSI Payback Fund. When an individual is approved for SSI, the federal government reimburses the District for the IDA benefits the individual received. These reimbursement dollars are used to support the annual budget, and unspent funds are put into the SSI Payback Fund at the end of the year so the District can provide benefits for future IDA applicants.

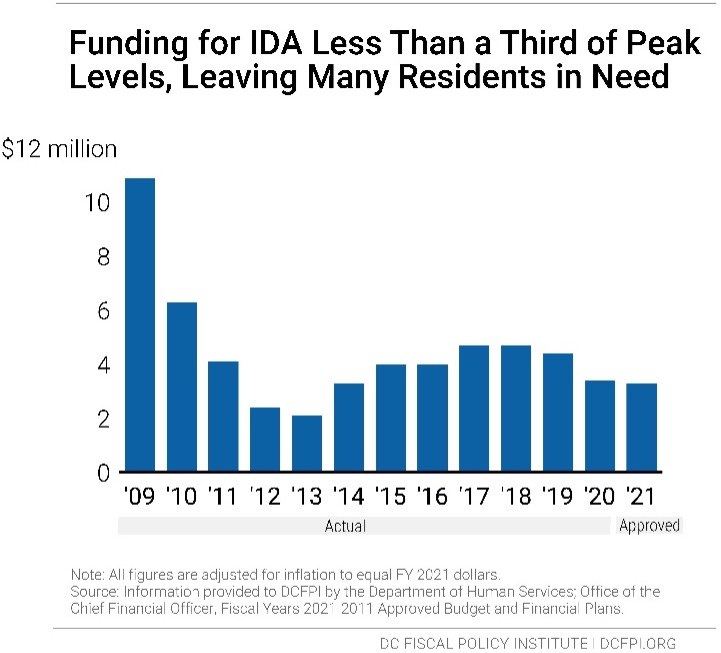

The total FY 2021 budget for IDA is $3.3 million, combining $2.5 million in local funding with $800,000 in federal reimbursement funds. This is less than one-third of the program’s FY 2009 peak funding level of $10.9 million and $1 million less in local funds than were allocated in FY 2019 (Figure 1).

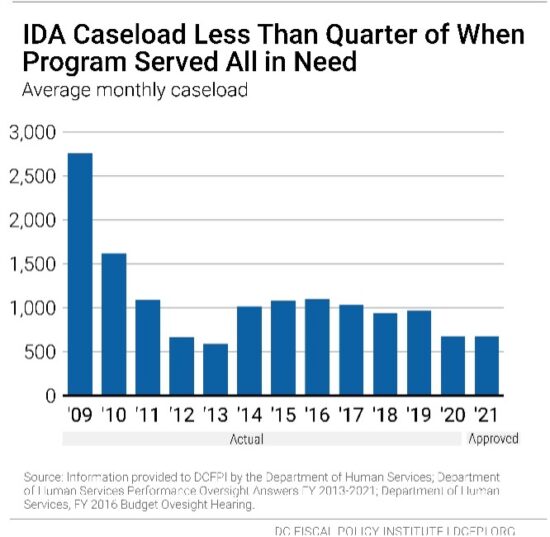

In 2009 when all residents in need received IDA, around 2,750 residents per month were served. Because of the limited budget, only 673 people per month are receiving benefits in FY 2021 (Figure 2). Without the budget cap, DCFPI estimates that the same number of residents need benefits today. DCFPI recommends that the District double the IDA caseload to 1,346 in FY 2022 with a $3.3 million investment, with the goal of expanding the program to serve all in need within 5 years. This could be funded with federal stimulus funds in FY 2022 and funded with local funds starting FY 2023.

The District Should Fund Legislation that Reduces Barriers to Alliance Enrollment and Recertification

I encourage the District to fund the “Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Query and Omnibus Health Amendments Act of 2020” which will ensure that the DC Healthcare Alliance has low-barrier application and recertification requirements. The Alliance is a program that provides critical health care coverage to residents with low incomes who do not qualify for Medicaid, most of whom are immigrants. Healthcare is a human right and truly vital during the current COVID-19 pandemic. The District should be doing all it can to ensure that as many residents as possible have access to insurance and that access is as easy as possible. DC should do this by removing onerous recertification requirements in the Healthcare Alliance.

Given their shared purpose, the DC Healthcare Alliance and Medicaid program should have identical, low-barrier application and recertification requirements. But the DC Healthcare Alliance requires participants to recertify every 6 months and does not allow participants to do this online while Medicaid only requires annual recertification and allows participants to do so online. These barriers contribute to both poor health outcomes and unnecessarily high program costs.[2] We shouldn’t erect higher barriers just because a resident is undocumented—DC is a welcoming city, and our policies should reflect that value.

We thank the administration for ensuring that no one loses eligibility during the public health crisis by temporarily waiving the in-person interview requirement for the Alliance, but we need permanent changes to Alliance application and recertification procedures to build a just recovery.

Shortened Eligibility Period Has Led to Turnover, Poorer Health, and Higher Costs

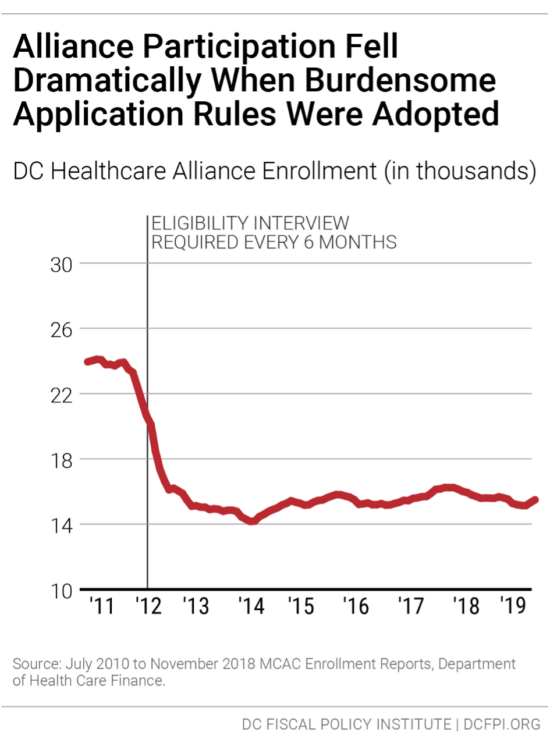

In 2011, DC implemented restrictive procedures residents had to follow to maintain their Alliance eligibility, including in-person interviews every six months, whereas Medicaid only requires annual recertification and no in-person interviews. The change in Alliance immediately led to a sharp drop in participation (Figure 3). Today, thousands of residents who should have health insurance do not, and the uninsured rate is much higher among Latinx DC residents[3] than others.

The restrictive rules also contribute to a high rate of turnover in the Alliance, as residents join the program but then drop off, due to the time-intensive requirements. Only 55 percent of Alliance participants renew their eligibility when it comes up, data from the District’s Department of Health Care Finance show.[4]Given that many Alliance members are working at jobs without paid leave and that visiting a Department of Human Services center can take an entire day or longer, it is not surprising that many are not able to renew their benefits.

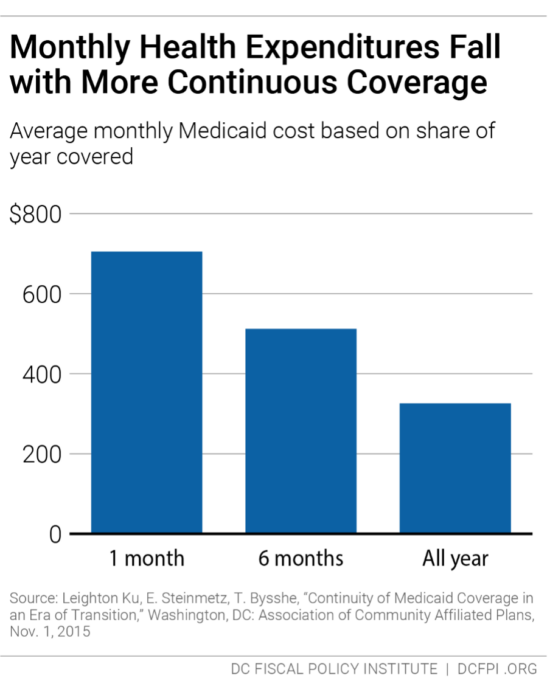

This lack of continuous coverage contributes to poor health outcomes and high costs per person in the Alliance. Churn from frequent recertification increases health program costs because it limits access to preventive care, which means participants often are sicker when they re-enroll, and because sicker residents are most willing to go through the process of maintaining coverage. Healthcare Alliance costs have doubled in the past four years, even though participation has not grown. The cost increases appear to reflect other factors, including a growing number of older participants.[5]

The six-month recertification requirement also creates problems for other residents seeking public benefits. Data collected in 2015 suggest that Alliance recipients make up one-fourth of service center traffic in a given month, even though they represent a very small portion of service center clients.[6]

It is worth noting that DHCF director Turnage and senior staff met several times over the past year with DCFPI and other advocates to discuss this issue, and we appreciate their openness. DHCF staff also engaged in some analysis of Alliance participants, and in my opinion, the research did not point to widespread fraud. This is important given that concern over possible fraud is the primary argument made by DHCF for keeping the current 6-month recertification rule.

- For example, there is concern that some non-residents use a fake DC address to apply for the Alliance, and that in some cases, many people use the same address. But DHCF’s analysis found that only 6 percent of Alliance participants are in homes with five or more Alliance participants.[7]

- DHCF also compared participants who cycled on and off with those that cycled off and did not return—with the possibility that some of those who didn’t return may have been on the Alliance fraudulently. But DHCF found the characteristics of those who cycled off permanently to be roughly the same as those who cycled off and on. For example, roughly the same share in both groups had a connection to a non-DC address. The similarity suggests that people who cycle off permanently may be eligible but simply discouraged from remaining on the Alliance by burdensome rules.

Research from Medicaid, for example, shows that average health care costs go down the longer participants have coverage (see Figure 4). DCFPI recommends the agency look at recipients who normally would have cycled off the Alliance but did not because of the waiver of the recertification requirement during the public health crisis to see how the longer coverage affected their health and health care costs.

DC has been a leader in expanding health insurance coverage to improve resident health and reduce health disparities. Eliminating barriers to care is a critical component of those important city goals and would go a long way towards affirming support for our immigrant neighbors. This is particularly important now as Latinx residents have the highest incidence of coronavirus infection per capita in the District, at 1,200 per 100,000 people compared to 820 and 175 per 100,000 people for Black and white residents respectively.[8] These residents need health insurance so they can receive the care they need.

Thank you for the chance to submit this testimony.

[1] “597 Days and Still Waiting.” Terrence McCoy. The Washington Post. 11 Nov. 2017. http://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/local/2017/11/20/10000-people-died-waiting-for-a-disability-decision-in-the-past-year-will-he-be-next/

[2] Ed Lazere, “No Way to Run a Healthcare Program: DC’s Access Barriers for Immigrants Contribute to Poor Outcomes and Higher Costs,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, revised March 17, 2019, https://www.dcfpi.org/all/no-way-to-run-a-healthcare-program-dcs-access-barriers-for-immigrants-contribute-to-poor-outcomes-and-higher-costs/

[3] Jodi Kwarciany, “DC Has Disparities in Health Coverage Despite Its Low Uninsured Rate,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, revised September 25, 2017, https://www.dcfpi.org/all/dc-disparities-health-coverage-despite-low-uninsured-rate/

[4] Ed Lazere

[5] Ibid

[6] Wes Rivers, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, and Chelsea Sharon, Legal Aid Society of the District of Columbia, “Testimony for Public Oversight Hearing on the Performance of the Economic Security Administration of the Department of Human Services District of Columbia Council Committee on Health and Human Services,” revised March 12, 2015, https://www.legalaiddc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/CSharon3.12.15.pdf

[7] Department of Healthcare Finance information provided to DCFPI and partners.

[8] Natalie Delgadillo, “Why Do Latinos Have The Highest Rate of Coronavirus Infection in D.C.?,” Dcist, May 11, 2020, https://dcist.com/story/20/05/11/why-do-latinos-have-the-highest-rate-of-coronavirus-infection-in-d-c/