Budget and Revenue Highlights

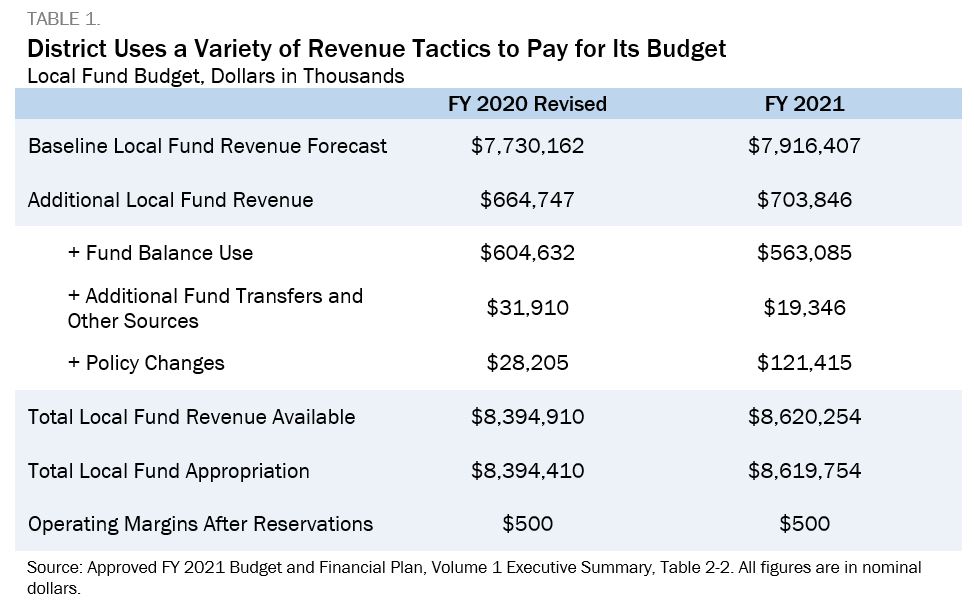

- $8.6 billion: The total FY 2021 Local Fund budget, representing a 1.8 percent increase over the revised FY 2020 budget, after adjusting for inflation.

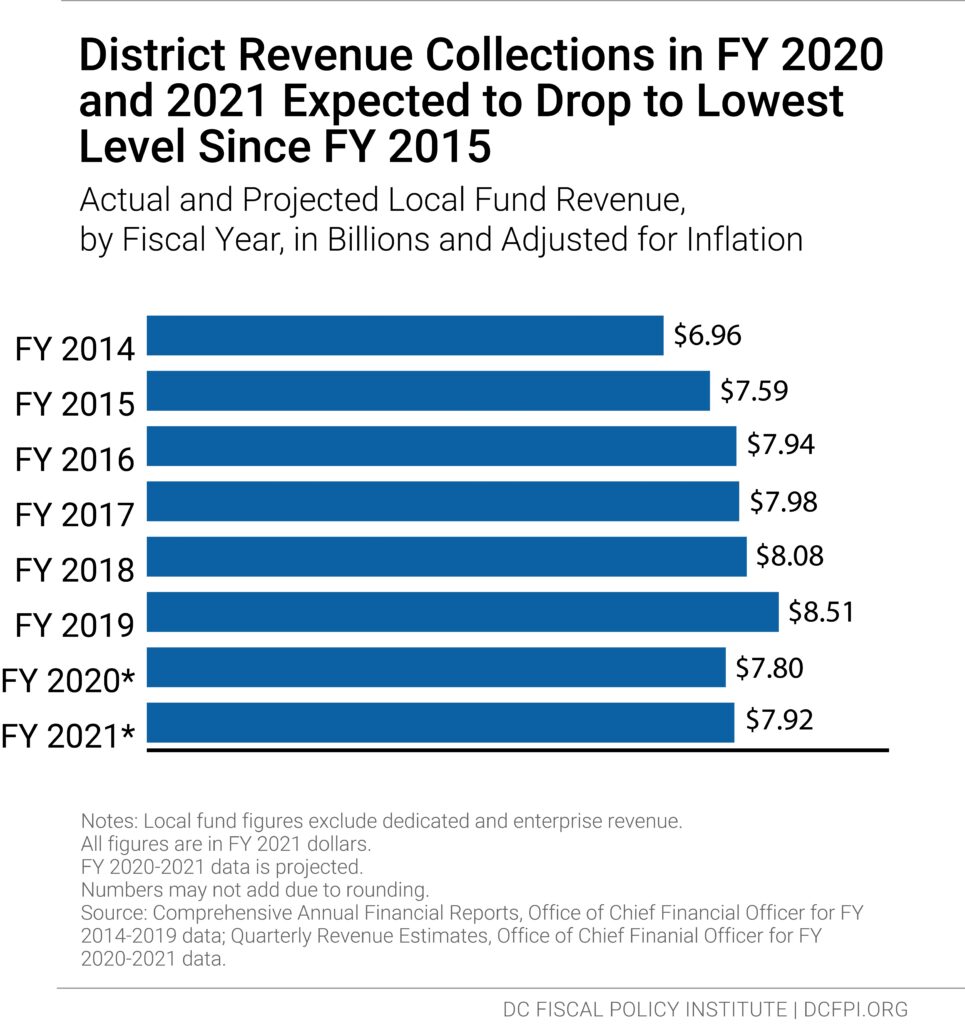

- $7.9 billion: DC’s projected baseline Local Fund revenues in FY 2021.

- $774 million: The projected drop in revenues for FY 2021 in the April forecast compared to the February pre-pandemic forecast. The total projected drop in FY 2020 plus FY 2021 is $1.5 billion.

- $703.3 million: The gap between Local Fund expenditures and baseline revenues before revenue tactics are included to help balance the budget.

- $703.8 million: Additional Local Fund resources—including fund balances and revenue increases—employed to help balance the budget. This includes revenue policy changes totaling $121.4 million.

The COVID-19 pandemic created an unprecedented spike in joblessness, resulting in enormous financial hardship for DC residents and small businesses and deepening racial income and wealth inequities. The economy’s rapid decline triggered a District budget crisis for both the current 2020 fiscal year (FY) that ends in September and for FY 2021, which begins in October 2020. While the full magnitude of this crisis is not yet clear, revenues are declining sharply: initial estimates of the damage in April show that the District expects revenues to plummet by $1.5 billion through the end of FY 2021.[1] Yet, costs are rising sharply due to a spike in demand for public services that help residents keep safe and make ends meet.

Black DC residents have borne most COVID-19 deaths, face double-digit unemployment rates, and are likelier to be low-wage employees on the front lines as well as business owners left out of federal COVID-19 relief.[2] The pandemic is exacerbating deeply entrenched inequities stemming from a legacy of government-sanctioned racism and discrimination. Fiscal policy can help the District blunt the harm of the recession and reverse course: with political will, tax policy can be a tool for racial justice and opportunity.

As more residents received pink slips, turned to food banks, and fell behind on rent, DCFPI and other advocates put forward a set of “just recovery” principles to encourage District lawmakers to use the budget process as a tool to ensure our city comes out of this crisis stronger than before.[3] We called on policymakers to pass a budget that advances racial justice, puts people first, and protects residents and small businesses experiencing economic hardship. And above else, we called on them to enact bold revenue policies to reverse the economy’s fall and mitigate this once-in-a lifetime crisis.

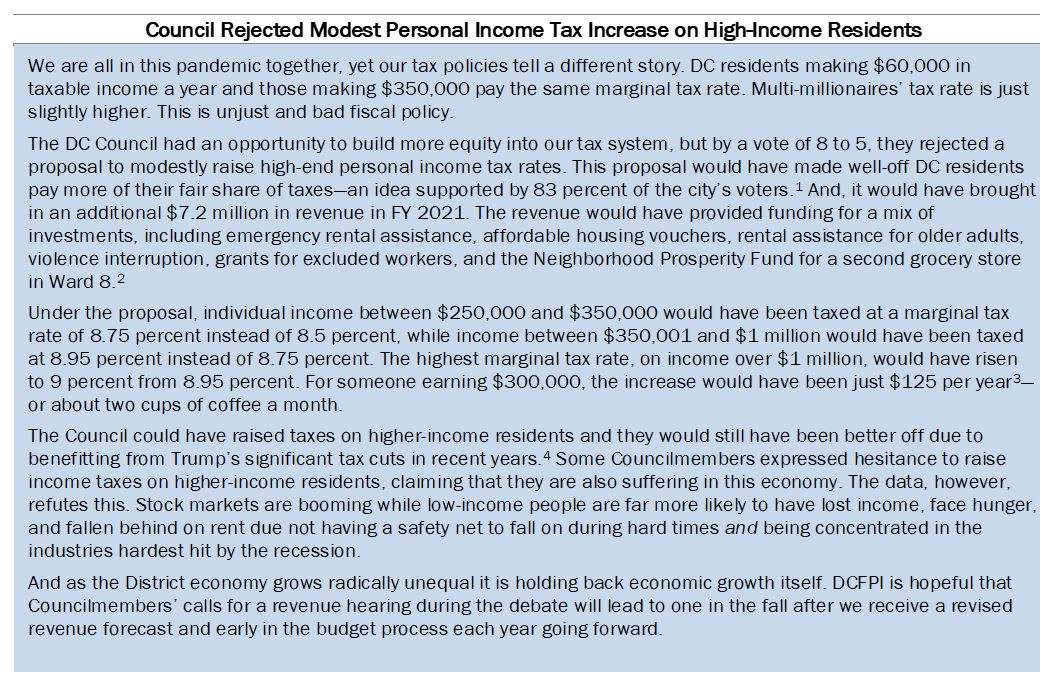

In July, the DC Council approved both a revised FY 2020 budget to address the mid-year shortfall and a four-year FY 2021-24 budget and financial plan. Lawmakers employed a variety of fiscal tactics—such as using reserves and federal relief dollars, freezing vacant positions, and adopting small revenue increases—to balance these budgets. While the FY 2021 budget protected, and in some cases expanded, vital programs, it failed to fully live up to what this unprecedented moment requires. Shortcomings include the rejection of a modest proposal that would have asked higher-income residents to pay more of their fair share of taxes, lack of sizeable cuts to the police budget, and failure to adequately finance homeless services, cash benefits for excluded workers, and childcare stabilization funding, among other needs.

Due to continued economic uncertainty, the April revenue forecast may not reflect the full damage that the pandemic is causing. The Chief Financial Officer (CFO) is expected to release an updated forecast at the end of September, and if revenues further plummet, the Mayor and DC Council will have to negotiate a FY 2021 budget revision to ensure the budget is balanced. If this were to occur, the District’s next policy response must be aligned with what DC residents deserve: a bolder vision that centers racial justice and generates the necessary revenue for a more inclusive economic recovery.

FY 2021 Budget Increases Spending

Due to the economic crisis, the Mayor and DC Council approved a revised FY 2020 budget to address a mid-year shortfall at the same time that they approved the FY 2021 budget, making many fiscal decisions with both budgets in mind. The revised FY 2020 budget reduces total Local Fund expenditures to nearly $8.4 billion, or by 2 percent, compared to the approved FY 2020 budget that lawmakers originally approved last year. Given the projected $722 million revenue loss in FY 2020 due to the pandemic, the cuts would have been deeper in the absence of budget freezes, use of the District’s reserves and fund balances, and creative fiscal strategies like refinancing debt. Deep budget cuts would have worsened the economic downturn that has been throwing many residents into financial distress.

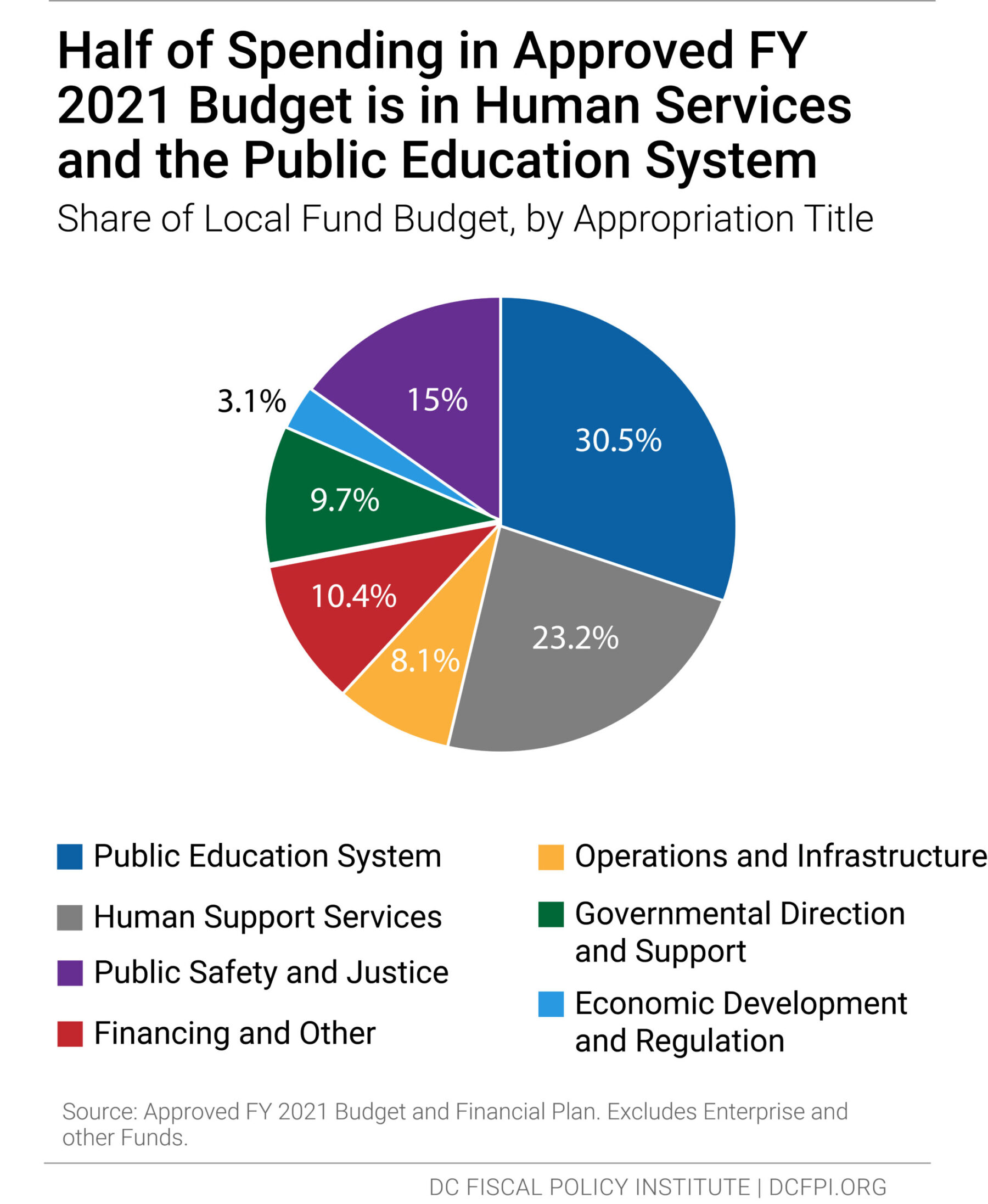

Despite the recession, the DC Council increased spending in the FY 2021 budget, which totals $8.6 billion. This is a 1.8 percent increase over the revised FY 2020 budget, after adjusting for inflation.[4] Of the total spending in the Local Fund budget, more than half of every dollar the District invests goes towards human services and the public education system (Figure 1). This is also where most of the spending increase is directed. The remaining money is invested in other public goods and programs—such as affordable housing, supports to small and Black-owned businesses, and core government services such as libraries and firefighters—that are funded under other appropriation titles.

The Pandemic is Causing DC Revenues to Plummet

The pandemic has ravaged parts of the District economy, reducing economic activity and causing revenues to decline quickly and sharply. The District’s Local Fund revenue consists of local tax and nontax revenue, like fines and fees. Local tax revenue—such as income, property, and sales taxes—makes up most of the Local Fund.

Compared to expectations in February, the CFO’s April forecast projected that the District would bring in $722 million less in revenue by the end of FY 2020 fiscal year and nearly another $774 million less by the end of FY 2021, for a total of $1.5 billion.[5] For context, this is more than the $1.43 billion the District had in cash reserves, or “rainy day funds,” before the pandemic hit.

In FY 2021, baseline Local Fund revenues are expected to come in at $7.9 billion, or 8.9 percent below pre-pandemic expectations in February. Aside from the current FY 2020, revenues haven’t been this low since FY 2015, once adjusted for inflation (Figure 2). The CFO doesn’t expect revenues to bounce back until FY 2022, with the caveat that there is great uncertainty in the coming year, such as a possible second wave of COVID-19 cases and inadequate federal relief, that could lead to further sizable changes to the April estimates.

Lawmakers Balanced the Budget Using a Variety of Tactics, Including Tax Increases

Lawmakers used a mix of revenue strategies to balance the FY 2020 and FY 2021 budgets. They should be commended for their resourceful leadership, but some of the decisions in the approved FY 2021 budget ask too much of some—such as city workers who won’t receive a cost of living adjustment unless the economy improves[6]—and too little of higher-income residents who could pay more of their fair share in taxes to mitigate the economic harm across the District.

In the revised FY 2020 budget, lawmakers closed the shortfall by reducing agency budgets, freezing vacant positions, shifting some District spending to federal funds,[7] and tapping various funds and carryover funding, among other tactics. On the revenue side, lawmakers found an additional $664.7 million in Local Fund resources to help balance the FY 2020 budget (Table 1).

The FY 2021 budget employs similar tactics to reach balance. In addition to baseline revenues, the budget uses $703.8 million in resources derived from the fund balance, transfers of enterprise funds and other sources, and revenue policy changes.

The fund balance reflects the reservation of funding in prior years that is budgeted for use in future years. It also includes other sources, such as $161.8 million from the FY 2019 surplus that would have been deposited into the Housing Production Trust Fund if not for the recession and the entire $213 million Fiscal Stabilization Reserve Fund.[8] This reserve fund is one of the District’s four cash reserve accounts, with approximately $1.2 billion remaining in the other three cash reserve accounts in FY 2021. The District is set to begin repaying this reserve fund in FY 2023 and FY 2024. Advocates urged the DC Council to use more (but not all) of our reserves given the high demand for rental relief and other health and human services, but the DC Council failed to take that approach.

As required, both budgets maintain an operating margin of $500,000 each year of the financial plan.

Budget Raids Birth-to-Three Funding from the Sports Wager Tax

While outside of the Local Fund budget, it is worth noting that the approved General Fund budget zeros out the portion of the sports wager tax that is dedicated to implementing part of the Birth-to-Three for All Act. This represents a loss of $3.6 million between FY 2020 and FY 2024.[9] It is unclear how lawmakers used these dollars in their budget. (See our Early Childhood Development Toolkit to learn more about the importance of this law for children, providers, and our broader community.)

Revenue Changes in the Budget

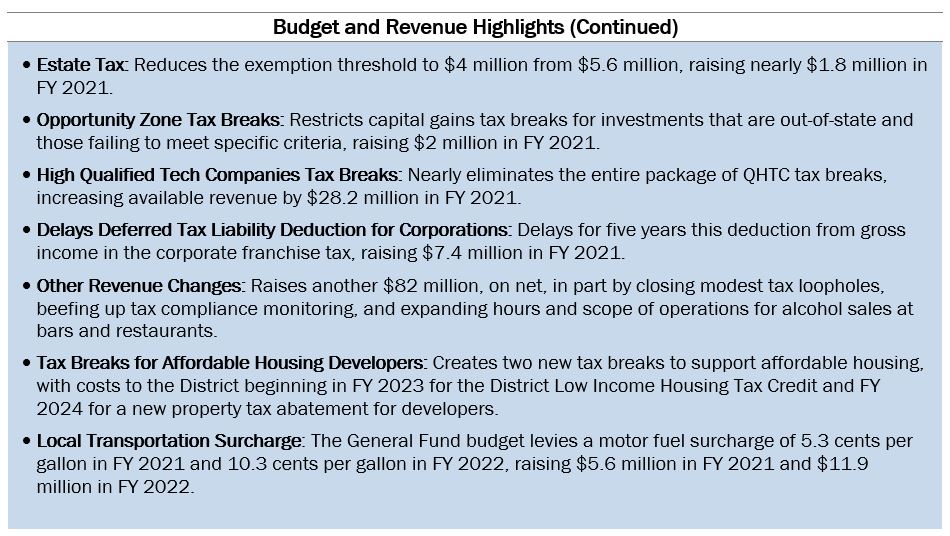

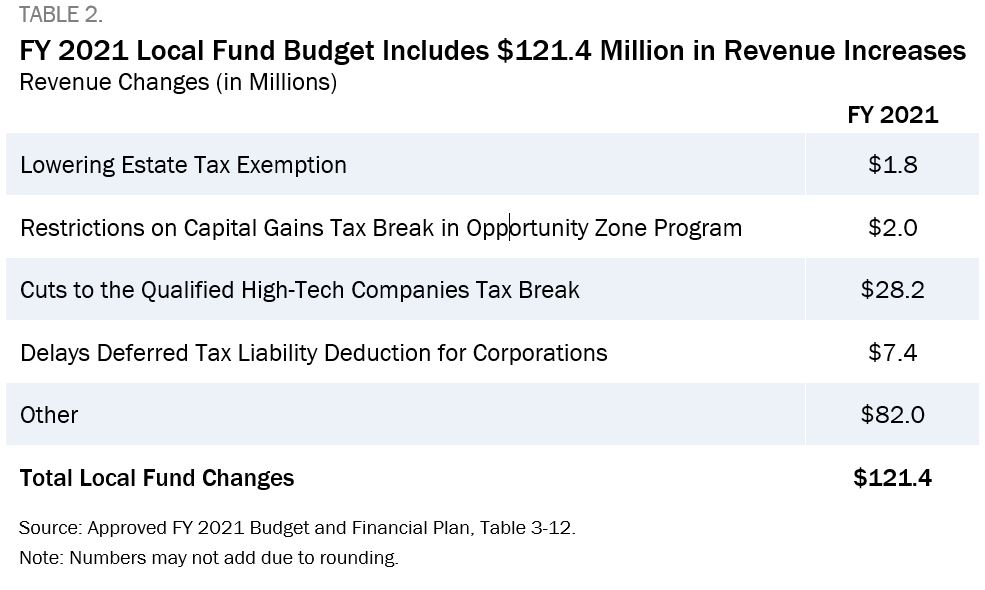

The FY 2021 budget includes $121.4 million, on net, in revenue increases to support vital programs and services (Table 2). This is 1.4 percent of the budget—a modest level given what these unprecedented times require. District lawmakers raised revenues by strengthening the estate tax, slightly scaling back capital gains tax breaks in the Opportunity Zone (OZ) program, and cutting and eliminating corporate tax giveaways, among other changes. Some of the new funding allowed for new or expanded investments in school-based mental health, youth programs, cash for excluded workers, and violence interrupters.

The FY 2021 budget has significant shortcomings even with these modest revenue increases, largely because the DC Council failed to put forward a truly bold revenue strategy in the face of a $1.5 billion revenue shortfall. Shortcomings are also in part related to them voting down a modest personal income tax increase on high-income residents. (Breakout Box below)

Strengthens the Estate Tax

The FY 2021 budget strengthens DC’s estate tax, our most progressive revenue source and tool for reducing wealth inequality. Over time, lawmakers have substantially weakened the estate tax by repeatedly increasing the size of estates that are allowed to be passed to heirs completely tax free. This “exemption” amount went up from $1 million to $2 million in tax year 2017, eventually climbing to $5.6 million in year 2018.[14] The budget reduced the exemption to $4 million in tax year 2021, raising nearly $1.8 million in FY 2021 and $9.2 million across the entire financial plan.

The funding will support a wrap-around approach for youth harmed or at-risk of violence, including violence interruption, mentoring, and mental health outreach at schools and in the community.

Restricts Capital Gains Tax Breaks in OZ Program

While the FY 2021 budget failed to end local capital gains tax breaks through the federal OZ program, it restricts local tax breaks for investments that are out-of-state and those failing to meet specific criteria. The changes will raise $2 million in FY 2021 and $19.9 million across the life of the financial plan.

DCFPI advocated for Council to fully decouple the District’s corporate franchise and personal income tax code from the federal OZ law. This change would require capital gains income associated with OZs to be taxed in the normal fashion, as ordinary income. There is already considerable national evidence that the program is turning out to be a windfall for rich investors rather than benefiting the low-income zone residents it was ostensibly intended to help.[15] Further, OZ programs could fuel displacement and gentrification, and they are under federal investigation for enriching political supporters. If the federal government wants to give another tax break to investors they can, but it doesn’t mean that DC should follow suit.

Repeals Most of the Tax Breaks for High Qualified Tech Companies

The budget nearly repealed the full package of High Qualified Tech Companies (QHTC) tax breaks, which are ineffective and poorly targeted. This increased available revenue by $28.2 million in FY 2021 and $137.9 million across the financial plan. Many of the companies claiming the tax break are primarily located outside of the District and not contributing to economic growth, an analysis from the Office of Chief Financial Officer found.[16] Tech companies can still receive a credit for retraining employees with barriers to work, though the budget lowers it to $10,000 from $20,000.

The funding will support vital programs, including homeless services, health insurance for undocumented residents, cash aid for excluded workers, school-based mental health services, and grants for early childhood providers.

Delays Deferred Tax Liability Deduction for Corporations

The budget delays for five years the Deferred Tax Liability Deduction (a deduction from gross income) in the corporate franchise tax that would have begun benefiting corporations when they paid their 2020 tax bill in calendar year 2021. This deduction allows publicly traded companies to receive a generous tax break to offset a “paper” expense that some corporations like Amazon must report on their financial statements. The delay raises $7.4 million in FY 2021 and nearly $29.8 million over the life of the financial plan. Deductions are delayed until tax year 2024.

This funding will support emergency rental assistance, affordable housing, excluded workers, violence prevention, and school based mental health.

Creates Tax Breaks for Housing Developers

In the budget, lawmakers approved two new tax breaks for housing developers to support the development or redevelopment of new affordable housing. Both measures are delayed to the latter years of the four-year financial plan.

The budget creates a District Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) that is based on the federal credit. Starting in October 2021, the program will automatically give 10-year credits to projects that receive federal LIHTC awards. The local credits will be equal to 25 percent of the value of the federal award. Projects that receive these awards can take advantage of these tax credits once the projects are complete, meaning that the District will unlikely bear any major cost of this program until FY 2023 at the earliest. This program reduces available revenue by $1 million in FY 2023 and $6 million in FY 2024.

The budget also creates a new property tax abatement program to incentivize the development of affordable housing in areas of the city with little affordable housing. Projects will be subject to first source hiring requirements and contracts with Certified Business Enterprises for a portion of project operations. The program will begin in FY 2024, with total funding for abatements capped at $200,000 that year and $4 million annually thereafter. To qualify for the abatement, properties must be in areas where there is little affordable housing—that is, Rock Creek West, Rock Creek East, Capitol Hill, and Upper Northeast. At least one-third of the units within each property must be affordable and set aside for up to 40 years to tenants with incomes at 80 percent of median family income, on average, or those with incomes up to $100,800 for a family of four.

While the geographic targeting is laudable, this income threshold is high, failing to incentivize the development of housing for the neediest renters. Additionally, the abatement as designed will pay for the cost of each affordable unit within 15 years, not 40 years, meaning there is no need for a longer-term tax break. Lawmakers should improve the program design in future legislation.

Adopts Other Revenue Changes

FY 2021 Local Fund budget raises another $82 million, on net, in part by closing modest tax loopholes, beefing up tax compliance monitoring, and expanding hours and scope of operations for alcohol sales at bars and restaurants. Nearly half of the funds raised is a result of transferring $40 million out of the Ballpark Revenue Fund, provided sufficient revenue is first collected for debt service due on the Ballpark Revenue Bonds. The District has been paying down its Ballpark debt faster than required. To find money to help balance the budget, the Mayor delays how quickly the city pays back the Ballpark bonds.

Creates a Motor Fuels Surcharge

The General Fund budget levies a motor fuel surcharge of 5.3 cents per gallon in FY 2021 and 10.3 cents per gallon in FY 2022, raising $5.6 million in FY 2021 and $11.9 million in FY 2022. The surcharge will grow with inflation thereafter, and the revenue will finance local infrastructure projects in the capital budget. Motor fuel importers will pay a combined 28.8 cents per gallon in 2021 and 33.8 cents per gallon in 2022 due to the existing excise tax and new surcharge.

Last Minute Repeal of the Short-Lived Ad Tax

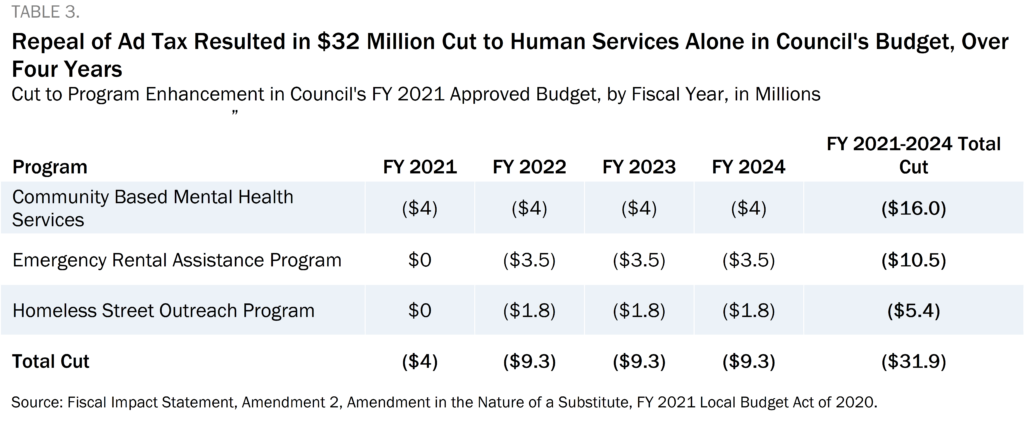

Just before approving the budget, the Council made a last-minute decision to undo a small advertisement tax increase on the planning, creating, placing, or display of advertisements for businesses that they approved earlier in the month, due to outcry from the business community and media outlets.

The Chair of the Council struck a backroom deal with other Councilmembers that removed the ad tax from the Council’s budget, without giving all Councilmembers or the public an opportunity to provide input. This created an $18 million gap in the Council’s budget. To plug the gap, the Council cut $4 million to mental health services in their budget, despite the public health and economic crisis, and found another $14 million through other cuts, funding shifts (such as moving funding from recurring to non-recurring), and borrowing. Under this ad tax repeal alone, there were nearly $32 million in cuts to health and human services enhancements over the four-year financial plan, forgoing the opportunity help more people who struggle to make ends meet (Table 3).

A moral budget would not have rolled back a small tax increase for businesses in the Council budget ahead of lifesaving aid for people suffering through the worst health crisis this country has faced in a century and an accompanying economic crisis.

Conclusion

We are in the middle of a once-in-a-lifetime crisis that requires bolder revenue solutions to meet the enormity of our challenges. We’re disappointed that the Council failed to approve very modest personal income tax increases on well-off DC residents, further scale back the police budget, and put forward bolder revenue changes. If revenues further plummet, all options to do more should be on the table, so communities being hit the hardest by the pandemic—and those who were suffering even before—are not further hurt.

[1] Compared to expectations in February, DC officials project that the District will bring in $722 million less in revenue by the end of FY 2020 and $774 million less in FY 2021, according to the Chief Financial Officer’s April revenue forecast. Office of the Chief Financial Officer, “April 2020 Revenue Estimates,” April 24, 2020.

[2] See: Doni Crawford and Qubilah Huddleston, “The Black Burden of COVID-19,” DCFPI, April 16, 2020; Jhacova Williams, “Latest Data: Black-white and Hispanic-white gaps persist as sates record historic unemployment rates in the second quarter,” Economic Policy Institute, August 2020; and, Doni Crawford and Qubilah Huddleston, “What Does COVID-19 Mean for the Survival of Black-Owned Businesses?,” DCFPI, May 1, 2020.

[3] Kate Coventry and Qubilah Huddleston, “Apply Recovery Principles to the District Budget: The Number,” Hill Rag, June 4, 2020.

[4] The year-to-year spending increase is 2.7 percent when the figures are not adjusted for inflation, using national CPI data. When compared to the FY 2020 approved budget, the FY 2021 budget is a 0.3 percent decrease, when adjusting for inflation.

[5] Projected revenue loss across the full four-year financial plan totals $2.5 billion.

[6] If recurring FY 2021 revenues come in above April 2020 projections by January 2021, a portion or all, depending on the size of the excess, of the funding will be used to honor cost of living adjustments for select collective bargaining agreements. While DCFPI appreciates the Council’s desire to fund these crucial investments, we oppose the mechanism to set aside “future” revenues for single priorities because it shortchanges the budget process and sets a bad precedent. Instead, as excess revenue comes in, the Mayor and the Council should evaluate current needs and decide how to allocate the revenue.

[7] Once these federal dollars expire, it will be important for District policymakers to find local dollars so these programs can continue to operate and meet current needs at that point.

[8] Ed Lazere, “Let’s Put DC’s Surplus to Work Helping DC Residents,” DCFPI, February 20, 2020.

[9] The Washington Post recently reported that the pandemic has caused sports wager revenues to come in far below projections, but the city expects the revenue collections to climb as the recession recedes. See: Fenit Nirappil, “A D.C. sports betting app was supposed to raise millions for the city. It’s off to a rough start,” The Washington Post, September 16, 2020.

[10] Natali Fani-Gonzalez and Gail Zuagar, “83 Percent of D.C. Voters Support Raising Local Taxes on Wealthy Residents: Results of a New Poll Call for Closing Ineffective Tax Loopholes for Corporations,” DCFPI and DC Action for Children, June 17, 2020.

[11] Eliana Golding, “DC Council Should Protect Revenue Increases at Second vote and Use More Reserves,” DCFPI, July 16, 2020.

[12] Charles Allen, “What’s in the DC Budget for Ward 6,” Hill Rag, August 6, 2020.

[13] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “TCJA by the Numbers: 2020,” August 28, 2019,

[14] The Estate Tax Clarification Amendment Act of 2018 decoupled the District’s estate tax exclusion threshold from the federal threshold and set the District’s threshold to $5.6 million.

[15] Jesse Drucker and Eric Lipton, “How a Trump Tax Break to Help Poor Communities Became a Windfall for the Rich,” New York Times, August 31, 2019.

[16] Office of the Chief Financial Officer, “Review of Economic Development Tax Expenditures,” November 2018.