- Allocates $14 million in cash assistance for excluded workers (includes $5 million in off-budget funds).

- Cancels scheduled cost of living adjustment to TANF and IDA benefits.

- Adds $10 million to cash assistance; $5.2 million of this funding comes from the elimination of small programs.

- Keeps IDA budget flat at $3.3 million.

- Adds $7.4 million so that Alliance recipients can complete the required 6-month recertification by phone rather than in person.

- Adds $6.3 million to the Alliance budget to cover anticipated increases in caseload and costs.

- Adds $75,000 to the Department of Health budget to implement outreach strategies for the Women, Infant, and Children program.

- Moves $250,000 of the Produce Rx budget to the Department of Health Care Finance so that the program can leverage federal Medicaid funding.

- Cuts $4 million from community-based behavioral health services for low-income residents.

Due to the economic crisis, lawmakers revised the fiscal year (FY) 2020 budget to address a mid-year shortfall and provide immediate relief to residents and businesses. They approved an FY 2020 supplemental budget at the same time that they passed the FY 2021 budget and made many decisions with both budgets in mind. This FY 2021 budget toolkit reflects some of the FY 2020 budget revisions.

During recessions people turn to safety net programs—such as food and cash assistance—to make ends meet. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a sharp increase in joblessness, higher than at any point in the Great Recession.[1]

The uneven harm of the pandemic, particularly on DC’s Black, Latinx, and immigrant communities, throw the inadequacy and inequality of our safety net into sharp relief. Systems designed to provide temporary help to struggling people are proving insufficient in this recession, as long-term job uncertainty persists.

Emerging data shows a sharp increase in hardship. Over 30 percent of children in DC are living in a household that is behind on rent/mortgage or didn’t get enough to eat due to the pandemic, according to a recent report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. This figure jumps to 50 percent when looking only at children renter household.[2]

The fiscal year (FY) 2021 budget addresses some, but not all, of these needs.

New Cash Assistance Program for Excluded Workers

The COVID-19 public health pandemic has caused an economic crisis and unprecedented challenges for the District. As we collectively face these challenges, it has become clear how interconnected we all are and how much the well-being of the District depends on the health and economic well-being of each one of us.

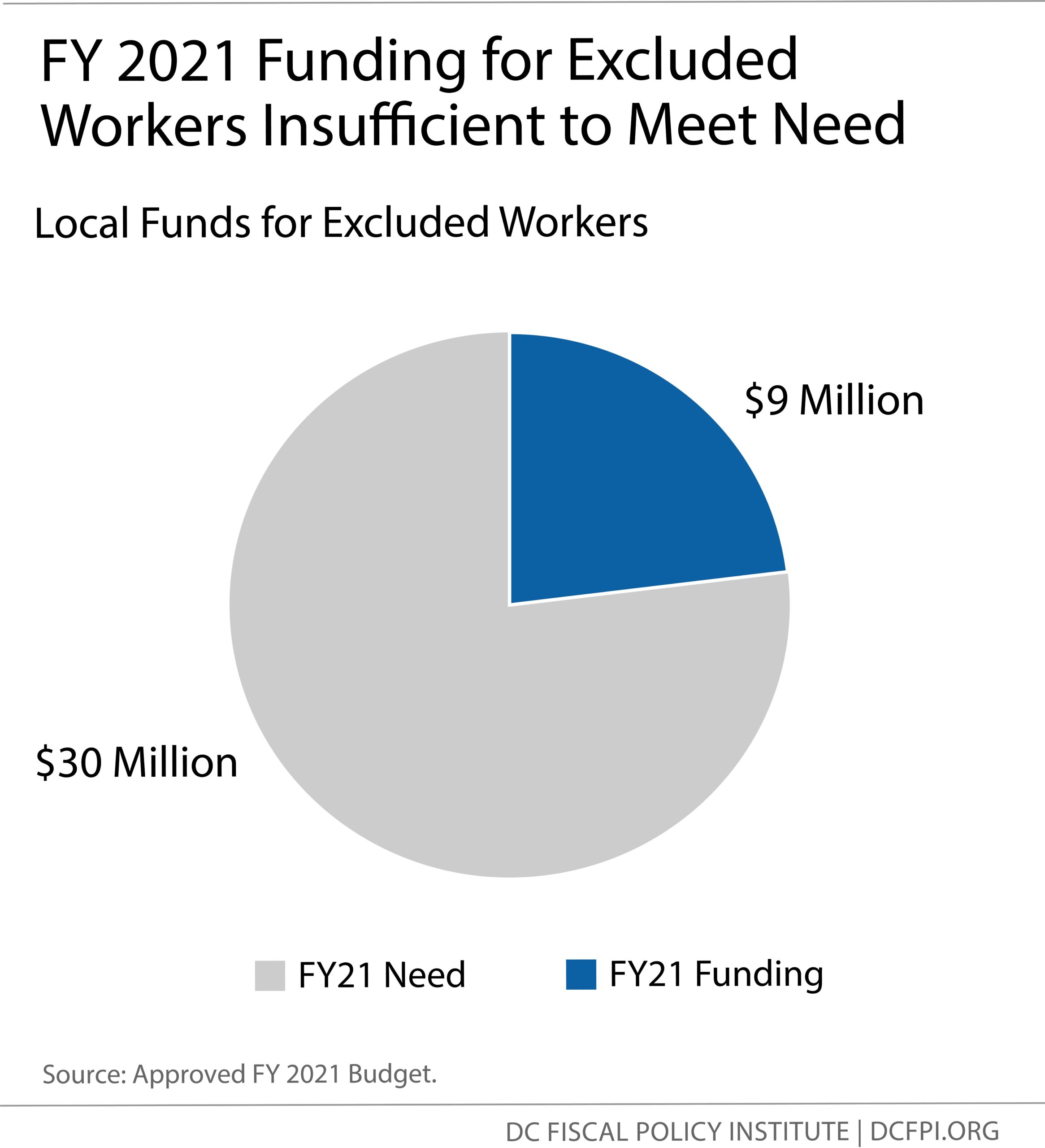

Unfortunately, federal lawmakers excluded certain residents—including those who are undocumented or otherwise in the informal cash economy—from federal relief efforts that provide vital income assistance to help with bills and basic needs. These excluded workers are essential. Policymakers approved $9 million dollars in the FY 2020 supplemental budget to provide cash assistance to help ensure that all DC residents—regardless of their profession or immigration status—can better make ends meet during this crisis.

This investment came after Events DC, the semi-public company in that owns and manages the Walter E. Washington Convention Center, RFK Stadium, and Nationals Park, invested $5 million from their FY 2020 budget to support undocumented residents with cash assistance in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.[3]

Still, the total funding of $14 million for excluded workers is well below the approximately $30 million needed to provide $1,000 in cash assistance for all excluded workers, based on advocates’ estimates (Figure 1).

DC is home to about 25,000 undocumented residents, based on a Pew Research estimate[4] and the DC Chief Financial Officer’s (CFO) analysis of the DC Alliance Program.[5] One thousand dollars in cash assistance for each of DC’s undocumented residents costs approximately $25 million. This figure doesn’t cover the entirety of DC’s excluded workers who are not immigrants but are excluded from UI and federal assistance because they are in the informal cash economy or are returning citizens. The DC Policy Center reports 2,800 returning citizens in DC each year who lack the recent job history needed to claim unemployment benefits.[6] Documented workers in the cash economy such as domestic workers, day laborers, sex workers, and street vendors who are also unable to claim UI benefits due to the informal nature of their work are also adversely impacted by the crisis. Given these workers are in the cash economy, advocates relied on partner organization with close ties to these communities and conservatively estimated the number of documented excluded workers in DC to be 2,000-3,000, putting the total number of excluded workers at 30,000.

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

The District’s Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program provides cash assistance, subsidized childcare, and employment resources to help families with children facing economic hardship. The program, operated by the Department of Human Services (DHS), is funded with a mix of federal and local funds.

Due to the COVID-19 crisis, the agency anticipates that more households will receive TANF in FY 2021 than in past years. To meet this need, the budget adds $10 million in one-time funding to cash assistance, with $5.2 million of this funding coming from the elimination of several small TANF programs—including the Family to Family program, the UDC Paving Access Trails for Higher Security (PATHS) program, and Tuition Assistance Program Initiative for TANF (TAPIT). Family to Family is a mentoring program where a TANF family receives mentoring from another family. PATHS offers a sixteen-week job skills experience—eight weeks of intensive instruction in workplace-oriented math and English followed by an eight-week career-specific internship program. TAPIT is a scholarship program for a two- or four-year degree. DHS reports that TAPIT is not needed as there are other aid programs that families can access.

The budget anticipates that the agency will have $5.2 million less in federal TANF carryover in FY 2021 than in FY 2020. Due to a bump in caseloads and increased costs in homeless services for families, the agency spent more of its annual TANF funding in recent years and has fewer dollars to carry over.

The budget reduces the Program on Work Employment and Responsibility (POWER) by $2.1 million to account for a drop in enrollment in recent years. POWER serves TANF families whose head of household is unable to meet program requirements due to incapacity, such as a physical health, mental health, or substance abuse problem. This budget reduction reflects the current, reduced POWER caseload.

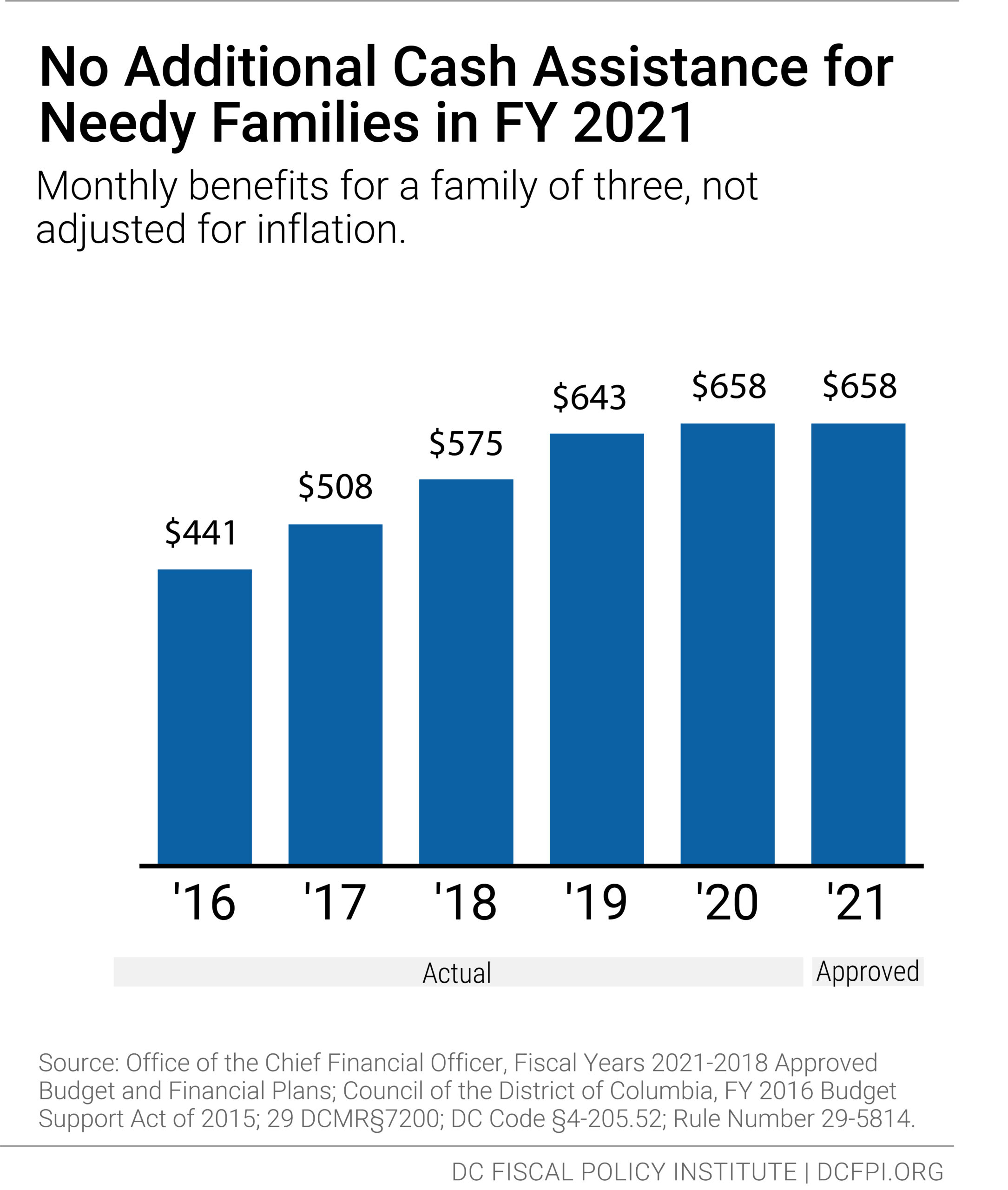

Planned Benefit Increase Cancelled

By law, TANF benefits are supposed to be adjusted for cost of living annually, but the Mayor cancelled this increase in FY 2021 due to the tight budget. The maximum benefit for a family of three will remain at $658 a month in FY 2021 (Figure 2).[7]

Interim Disability Assistance

Interim Disability Assistance (IDA) provides modest, temporary cash benefits to adults with disabilities who have applied for federal disability benefits, Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), and are awaiting an eligibility determination. IDA is a vital lifeline for DC residents who cannot work and have no other income or other means to support themselves. The wait for federal benefit determination has skyrocketed in recent years, from 350 days in 2012 to nearly 600 days in 2017.[8]

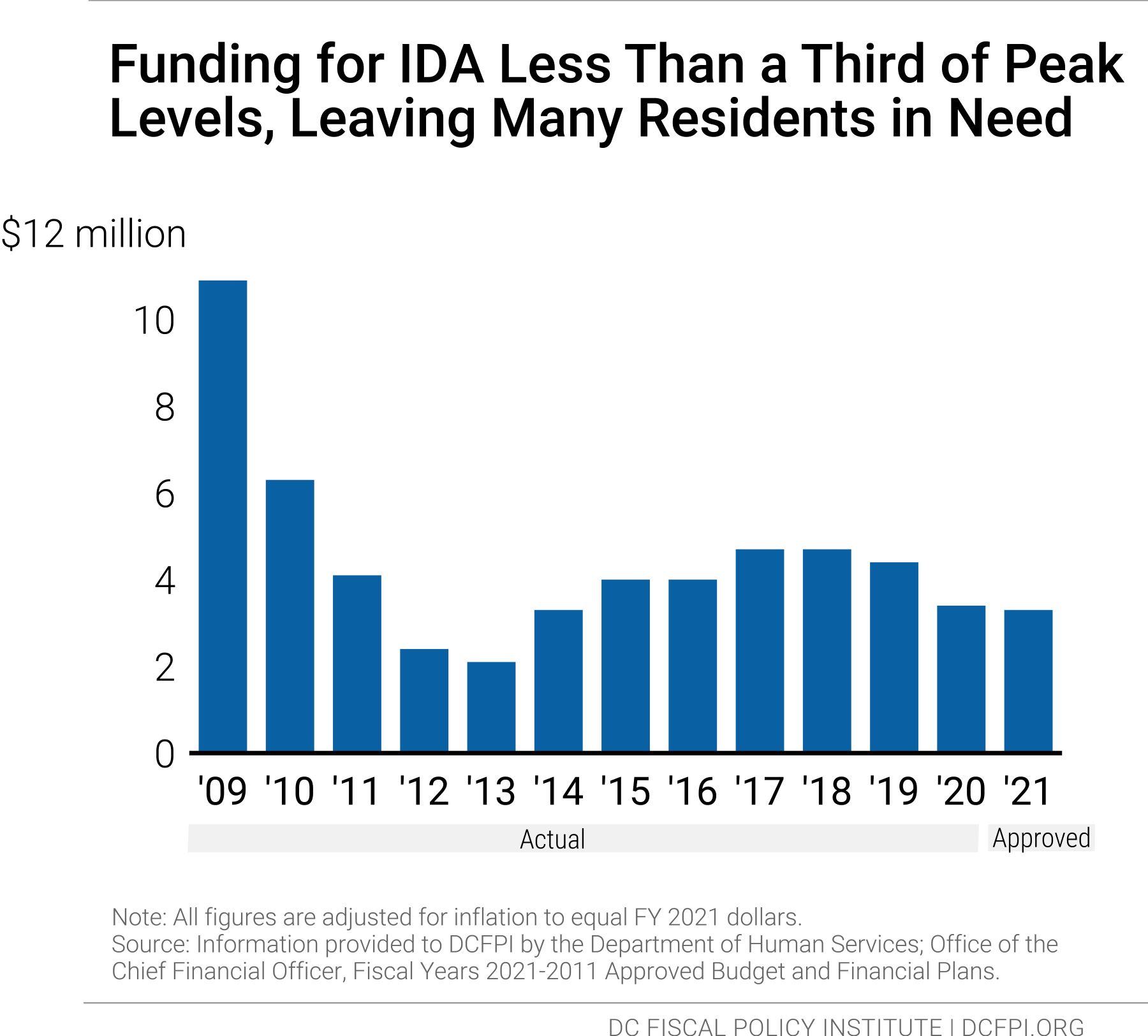

The total FY 2021 budget for IDA is $3.3 million, which is less than one-third of the program’s FY 2009 peak funding level of $10.9 million. The FY 2021 budget combines $2.5 million in local funding with $800,000 in federal reimbursement. Federal reimbursement funds come from the Social Security Administration. When an individual is approved for SSI or SSDI, the federal government reimburses the District for the IDA benefits the individual received. (Figure 3).

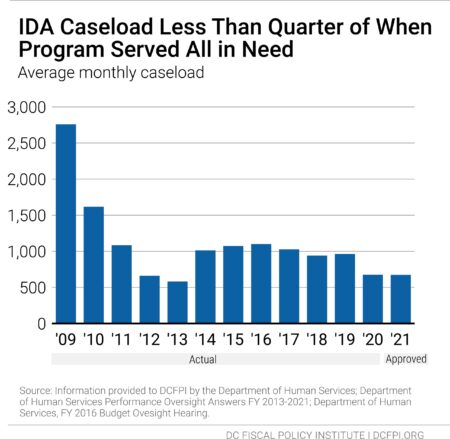

In 2009 when all residents in need received IDA, around 2,750 residents per month were served. Because of the limited budget, only 673 people will be served in FY 2021. The reduced funding and caseloads for IDA since 2009 suggests that many DC residents with disabilities have no regular source of income, since one of the prerequisites for applying for SSI is that an individual is unable to work. (Figure 4).

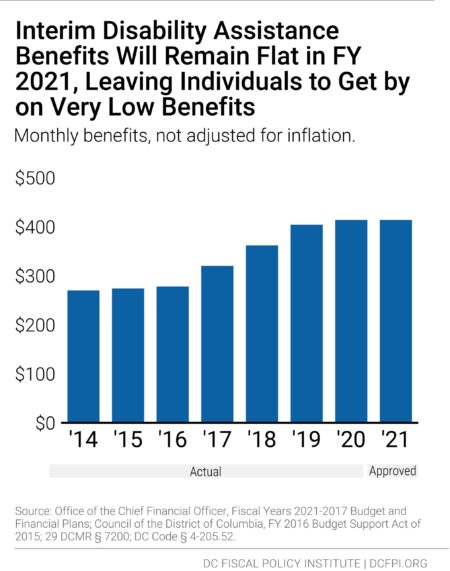

IDA Benefits Will Remain Flat in FY 2021

The IDA benefit level is tied to benefit levels in TANF. The IDA benefit equals the TANF benefit for a household of one person (such as a pregnant mother). By law, TANF benefits are supposed to be adjusted for cost of living annually, but the Mayor cancelled this increase in FY 2021 due to the tight budget. The IDA benefit will remain at $414 a month in FY 2021. (Figure 5).[9]

Budget Removes Some Barriers to Immigrant Health Care Access

The FY 2021 budget removes some barriers to accessing health care through the DC Healthcare Alliance—a local program that provides health insurance coverage to low-income residents who are not eligible for Medicaid.

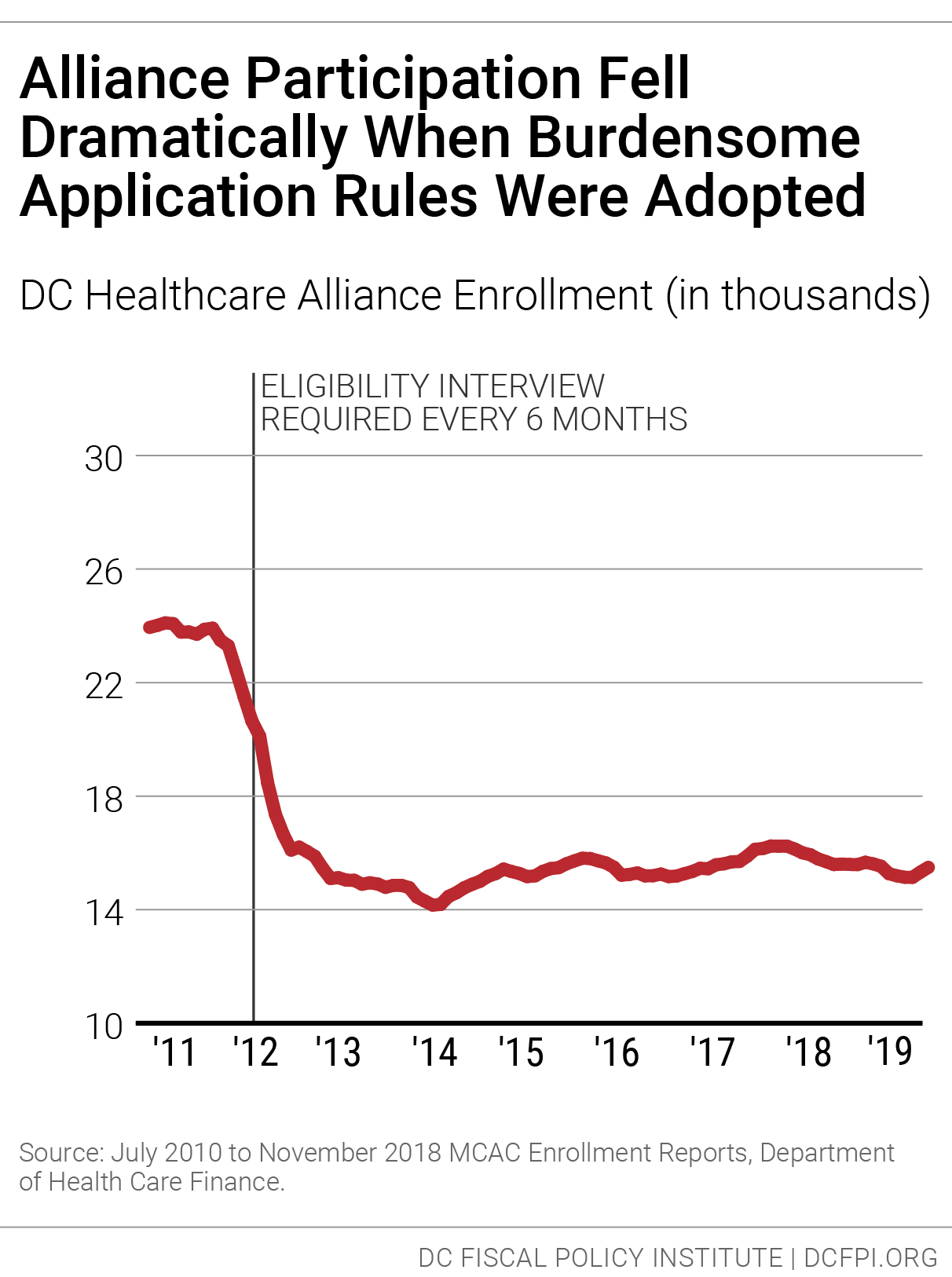

Because the federal Affordable Care Act allowed DC to move many Alliance participants to Medicaid, Alliance participants today are largely immigrants who are ineligible for Medicaid, including documented immigrants who have not yet met the five-year waiting period for federal benefits and undocumented immigrants. In 2011, DC implemented a new rule requiring participants to visit a DC social service center every six months to maintain their eligibility, instead of the annual recertification the city requires for other safety net programs. This created a barrier for maintaining Alliance coverage, leading to a sharp drop in Alliance enrollment. [10] (Figure 6).

The six-month recertification requirement contributes to a very high rate of turnover, or “churn.” Currently, only about half of Alliance participants renew their eligibility at the re-certification period. This means that many Alliance participants have only intermittent health coverage.

Churn from frequent recertification results in higher costs in health program because it limits access to preventive care, which means participants often are sicker when they re-enroll, and because sicker residents are most willing to go through the process of maintaining coverage.

The FY 2021 budget includes $7.4 million to replace the six-month re-enrollment requirement with an annual in-person requirement and allow participants to renew via phone for their six-month recertification. This will help participants maintain their coverage. The budget includes an additional $6.3 million to cover anticipated increases in enrollment and costs.

Public Health in the FY 2021 Budget

The Council directed $75,000 to the Department of Health to fund an outreach plan for the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Nutrition Program to develop strategies to increase WIC participation.

The Council also transferred $250,000 of the Produce Rx budget from the Department of Health to the Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF) so the agency can leverage to federal Medicaid funds to expand the resources available to the program. Under the Produce Rx program, doctors at participating clinics can write prescriptions for their patients who suffer from diabetes, pre-diabetes, or hypertension redeem for fresh produce at the Alabama Avenue Giant Food in Ward 8 at no cost.

Community-Based Behavioral Health

The FY 2021 budget cuts $4 million from the Behavioral Health Rehabilitation and the Behavioral Health Rehabilitation Local Match programs at the Department of Behavioral Health (DBH), compared to FY 2020 funding. The first program allows local behavioral health providers to bill for services provided to DC residents that receive mental health rehabilitation services that are only paid for by local dollars. This program also pays for behavioral health services that non-eligible Medicaid residents receive. The second program matches local dollars for providers who are paid through Medicaid and provide mental health and substance abuse disorder services to Medicaid-eligible residents.

The Mayor proposed to cut $9.5 million from DBH’s budget. While the Council’s restoration of some of this cut is laudable, thousands of DC residents—especially low-income residents—are facing increased isolation, economic insecurity, and other types of stress and trauma that make fully funded community-based behavioral health resources a necessity. Further, because the District receives $3.33 in federal money for every $1 in local funds spent on services provided through the Behavioral Health Rehabilitation Local Match Program, the Council’s failure to fully restore the other $4 million actually translates to a total loss of $8.6 million.[11]

[1] Chad Stone, “Robust Unemployment Insurance, Other Relief Needed to Mitigate Racial and Ethnic Unemployment Disparities,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 5, 2020.

[2] Arloc Sherman, “Children Facing Very High Hardship Rates,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 6, 2020.

[3] Events DC, “Events DC Announces DC Cares Program to Execute $5M Undocumented Workers Relief Package and $10M Cultural Grant Program,” June 5, 2020.

[4] Pew Research Center, “U.S. Unauthorized Immigrant Population Estimates by State,” February 5, 2019.

[5] Jeffrey Dewitt, “Fiscal Impact Statement – D.C. Healthcare Alliance Re-Enrollment Reform Amendment Act of 2017,” October 5, 2017.

[6] Robin Selwitz, “Obstacles to Employment for Returning Citizens in DC,” DC Policy Center, August 17, 2018.

[7] The Office of the Chief Financial Officer estimates that the cost of living adjustment (COLA) is 2.4%. Benefits will be increased by the actual Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U).

[8] Terrence McCoy, “597 Days. And Still Waiting,” The Washington Post, November 20, 2017.

[9] The Office of the Chief Financial Officer estimates that the cost of living adjustment (COLA) is 2.4%. Benefits will be increased by the actual Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U).

[10] Medicaid expansion through the ACA in 2010 shifted approximately 33,000 residents from the Alliance program to Medicaid. However, after a period of stable enrollment, caseloads began to decrease after a six-month, in-person recertification requirement began for all enrollees in FY 2012.

[11] Mark LeVota, Email communication, “Council Behavioral Health Math,” July 23, 2020.