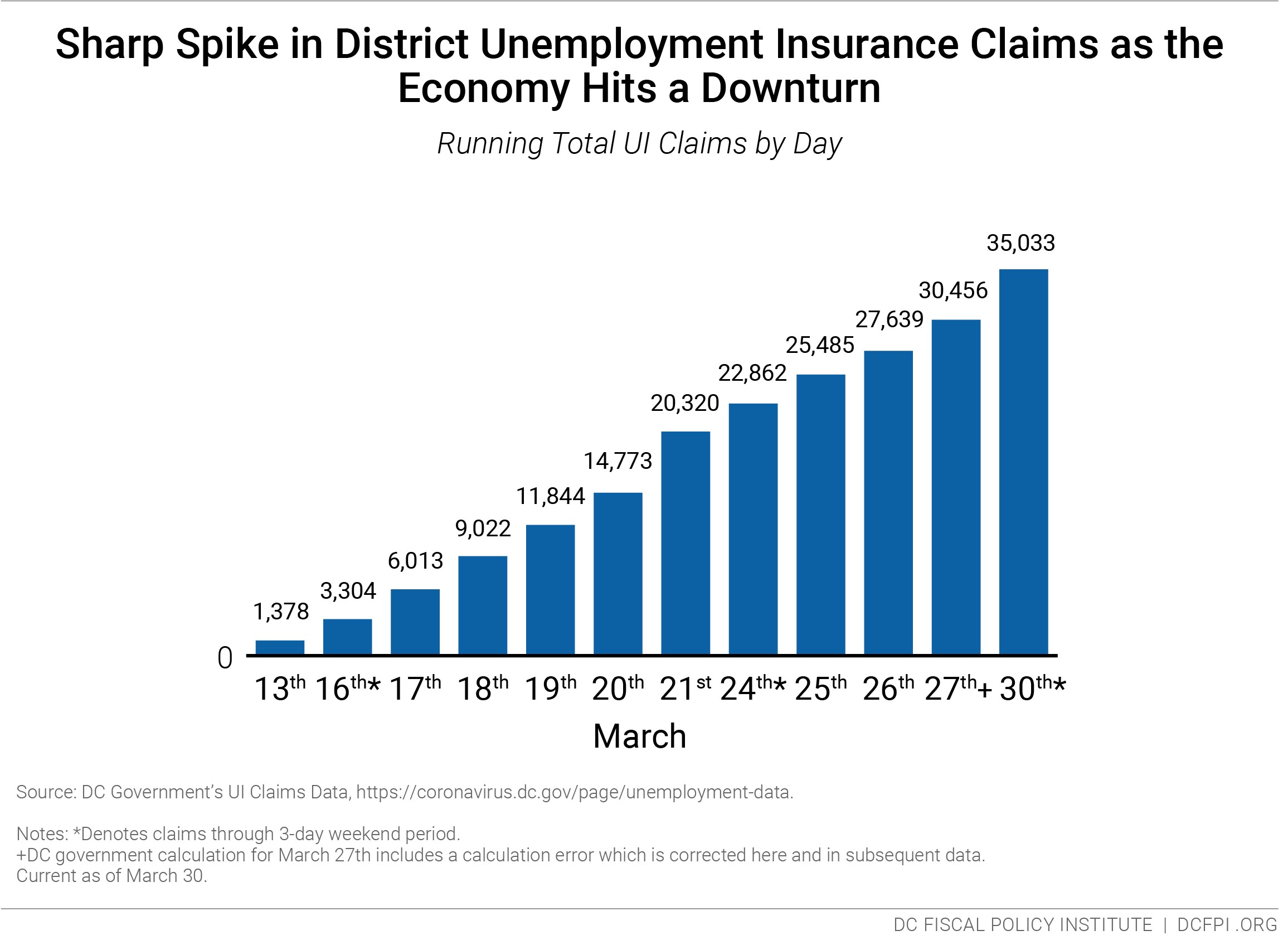

Coronavirus (COVID-19) is wreaking havoc on the District’s economy, leading to a spike in joblessness and health and human service needs. DC’s Department of Employment Services’ (DOES) daily raw count of unemployment insurance (UI) claims has spiked by 2,442 percent in the last two weeks—to over 35,000 on March 30 from 1,378 on March 13 (Figure 1). Economists are predicting that millions of jobs will be lost across the nation by summer, including more than 50,000 jobs here in the District—and that’s a modest estimate. District and national leaders have taken steps to provide immediate economic relief, but they must enact more substantial and structural policy changes to address public health needs and protect residents from grave economic harm long term. If they conduct policy as usual, it will hurt Black and brown workers the most, because they are often first to feel the impact of declines in our economy and the last ones to recover due to structural racism and a broken economic structure.

Due to a data lag, the recent spike in unemployment is not yet reflected in the government’s latest release of state employment numbers, which show an unemployment rate of 5.2 percent in the District in February 2020, unchanged from January. But the historic number of UI claims in March, and the forecasts of future job losses, suggest that the March 2020 unemployment rate, and beyond, will continue to climb. Earlier this month, the District’s Chief Financial Officer warned that the city may see unemployment rates as high as 20 percent.

Nationwide, UI claims increased by nearly 1,500 percent in the last two weeks—this is the highest level of claims ever recorded. Similarly, in the District, the spike in UI claims has been unprecedented. Case in point: the U.S. Department of Labor reported 13,473 actual claims (i.e., before adjusting for normal seasonal changes) for the week ending March 21 in its advance report issued last Thursday—this is the most DC has ever recorded in one week.[1] The loss of steady income for District workers surely means that families will struggle to pay bills and put food on the table, adding further stress during a global health pandemic.

These UI claims figures, however, are an underestimate of the total shock to the labor market. Economists expect these numbers to stay on the rise as the pandemic continues to wreak economic harm and as more people learn how to navigate the UI system and recently expanded benefits at the District and federal levels. Many jobless workers do not know that they qualify for UI, and as a result, they may delay filing a claim. There are reports that DC workers have found it difficult to file a claim due to an outdated application, technological issues with the system, and long wait times. Furthermore, we know that undocumented workers, self-employed individuals, new entrants to the job market, long-term unemployed, and misclassified workers do not traditionally qualify for standard unemployment insurance.

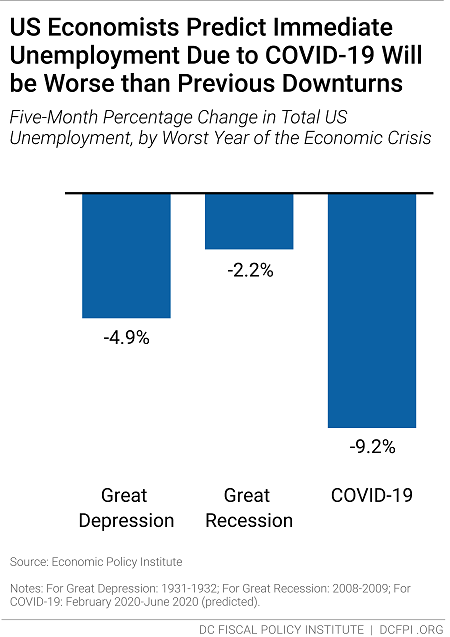

Moreover, economists predict that the immediate harm to workers due to COVID-19 will be worse than the labor market woes that we saw during both the Great Recession and Great Depression. The Economic Policy Institute forecasted that COVID-19 will cause a five-month decline in total US employment of 9.2 percent between February 2020 and June 2020 (Figure 2).[2] Comparatively, the size of the drop in total employment during the worst year of the Great Depression was only 4.9 percent. The size of the drop was 2.2 percent for the Great Recession—far lower than EPI’s estimate for 2020.

In response to COVID-19, District policymakers passed emergency legislation to expand UI benefits and unpaid medical leave, among other economic protections as they brace for widespread economic harm. Last week, Congress approved a federal stimulus package—the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act—to expand access to, supplement, and extend the duration of UI benefits to specific workers across different programs. While these actions will blunt some of COVID’s economic harm, they are short-term fixes, as many of the protections are temporary and most of the federal UI expansions expire by the end of the year. They also exclude undocumented workers. Additionally, the District is shortchanged in CARES, which provides us less than half of the aid that other states receive to respond to COVID-19 due to our lack of statehood.

We will continue to work at the federal and local levels to ensure that the economic harm to undocumented workers, low-wage workers, and people of color here in the District is limited. These policy changes should be long-term and structural to address longstanding racial and economic inequities.

[1] In this Thursday’s report for the week ending March 28, the count for the week of March 21 may be revised slightly.

[2] This data was shown during the Economic Policy Institute’s March 24th EARNTalks webinar, Unemployment Insurance Reforms Needed to Address the Current Crisis and Permanently Fill the Gaps.