The disappearance of affordable housing in DC has left most extremely low-income residents paying more than half their income on rent and utilities each month, putting enormous stress on family budgets and leaving many at risk of eviction and homelessness. Creating more affordable housing would not only help DC residents stay in their homes and communities, it would also dramatically increase their available income by lowering severely burdensome rents.

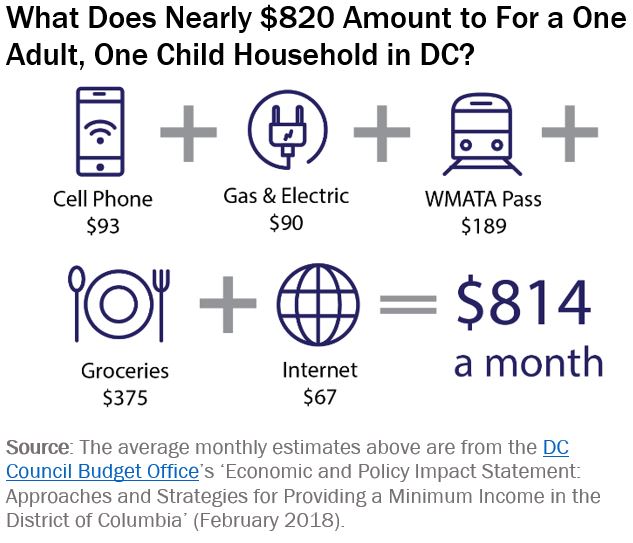

Reducing rents for DC’s lowest-income families to 30 percent of their income—the federal standard of affordability—would increase their income by an average of $820 per month, or almost $10,000 per year.[1],[2]

Adequate affordable housing is a racial justice issue. Residents of color represent nine out of ten households that pay more than half their income on rent, a result of the legacy of systemic racism institutionalized through racially restrictive covenants and government policies, combined with current barriers to opportunity.[3],[4] One-fifth of residents in Wards 7 and 8 are concerned that rising housing costs will displace them in the next three years.[5] Recent history supports their fears: over 20,000 Black DC residents were displaced from their neighborhoods between 2000 and 2013, according to a report by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition.[6]

Having hundreds of extra dollars a month would create more financially stable households that are better able to benefit from and participate in DC’s growing economy. With more disposable income,families would be able to buy more nutritious and adequate food, parents would be able to support their children’s education, and families would have easier access to health care.[7],[8] More disposable income in DC’s lowest-income communities would also help attract grocery stores, maintain local businesses, and support racially- and economically-diverse communities.

The District invests in a number of affordable housing tools, but these investments are not meeting the need. At minimum, the District should expand affordability by:

- Investing adequately in all of the District’s complementary housing tools to better serve extremely low-income households.

- Ensuring no deeply affordable housing units are lost during the DC Housing Authority’s “repositioning” plan.

- Investing in affordable housing units for larger families.

- Updating zoning to accommodate denser development near high-opportunity, transit areas.

- Expanding and strengthening rent control.

The District is uniquely positioned to address this challenge given its strong economy. DC has the resources to make sweeping investments in affordable housing programs that benefit families who have been excluded from DC’s growing prosperity.

Most Extremely Low-Income DC Renters Spend Half or More of Income on Housing

The District has approximately 39,500 extremely low-income renter households who pay over 30 percent of their income on housing—that’s enough people to fill the Capital One Arena more than three times over.[9], [10] Low-income renters struggle with rental costs more than they did a decade ago.[11] The share of renters struggling to pay rent has slightly increased since 2007, yet the share of homeowners struggling to pay their mortgages has dramatically declined during the same time period.

DC’s cost burden falls along racial and geographic lines. Wards 7 and 8, where approximately 90 percent of residents are Black, have the highest percentages of cost-burdened renters at 55 percent and 63 percent, respectively, compared to only 44 percent, on average, in the remaining six wards.[12]

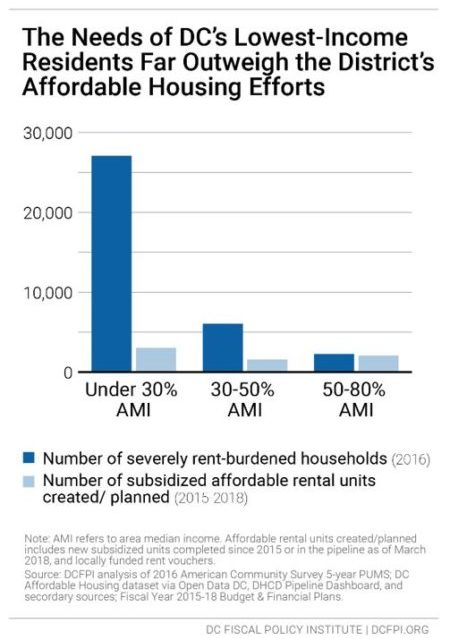

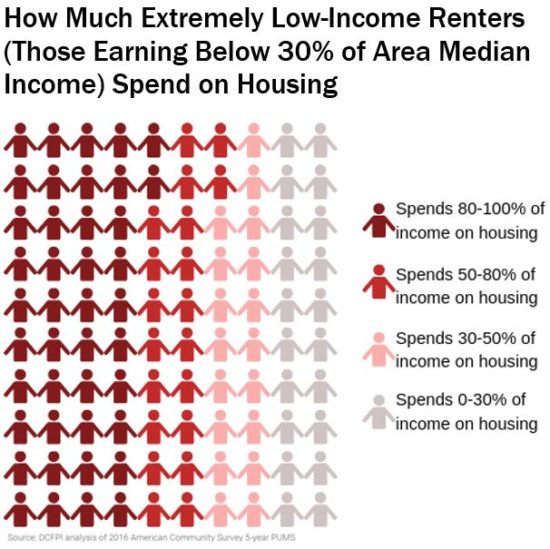

DC’s severe affordable housing challenges (i.e., paying more than half of income on rent) fall most heavily on extremely low-income renters, or those making under 30 percent of AMI. However, the District’s recent housing investments have barely made a dent in addressing the housing need among this income group (Figure 1). Whereas nearly two-thirds of extremely low-income households spend over half their income on rent, many pay 80 percent or more of their income on rent (Figure 2).

Some households may receive cash assistance or food assistance through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, but these programs do not guarantee even a subsistence level of income. Residents in this situation are forced to make grueling tradeoffs between rent and other necessities on a daily basis.

DC’s Affordable Housing Investments Do Not Reach the Lowest-Income Families

DC’s growing rental affordability challenge reflects the fact that incomes for extremely low-income households have remained flat while rising rents have eliminated nearly all low-cost housing options in the private market and affordability requirements have expired for countless buildings.[13], Throughout the District, the share of units renting for less than $1,000 per month fell by 38 percentage points from 1990 to 2017, when adjusting for inflation; during the same time period, rental units costing $1,600 or more increased over six fold.[14]

The District invests in a number of affordable housing tools, but these investments are not meeting the need.

- Nearly 40 percent of the “affordable” apartments the city has supported with public dollars in the last decade—from programs including the Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF), the Affordable Housing Preservation Fund (AHPF), Inclusionary Zoning, the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act, and tenant vouchers—are affordable to households making under 30 percent AMI.[15]

- HPTF, the city’s largest affordable housing tool, is required by law to direct at least 50 percent of its funds to housing for extremely low-income residents, but this target is rarely met.[16]

Just a fraction of households that are eligible for economic security programs receive them in part because demand for them far exceeds supply.

- Less than a quarter of families in the District receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families benefits received housing assistance during FY 2015 although their incomes qualify them for housing vouchers.[17]

- The DC Housing Authority’s waiting list for public housing is currently closed with 27,190 households already on the list, and the Housing Choice Voucher list is also closed with approximately 40,000 prospective applicants.[18]

Affordable Housing Would Mean Thousands of Additional Dollars in the Pockets of DC’s Lowest Income Families

Reducing the severe rent burdens that families with low incomes face would free up hundreds of dollars in their budgets every month, giving families resources needed to live healthier and more secure lives.

- Reducing rents to 30 percent of income for DC’s lowest-income families—those making under 30 percent of AMI—would increase available income by an average of $820 per month, or almost $10,000 per year.[19]

- Reducing rents to 30 percent of income for DC households at slightly higher incomes, between 30 and 50 percent AMI, would increase available income by an average of $575 per month, or nearly $7,000 per year.

- This increase in available income would make an enormous difference for families who struggle to meet their most basic needs after paying rent. An extra $820 per month could help with Metro fare, groceries, utility bills, school supplies, and a cell phone bill, among other expenses (Figure 3). It would greatly reduce the financial stress families face when nearly all of their limited income goes to rent.

- If all extremely low-income households paid only 30 percent of their income for rent, they would have over $365 million more in added income to spend in the local economy each year, before taxes. This is roughly what DC spends each year on the District Department of Transportation and the Child and Family Services Agency combined.[20]

Affordable Housing Creates Better Opportunities for District Families

Most DC families with extremely low incomes spend nearly all of their income on rent each month. Creating a rent ceiling of 30 percent of income for low-income households is essentially a monthly cash infusion that would help alleviate the constant burden of rent and utility payments.

Research demonstrates the positive impacts of having adequate family income.[21] The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is one of the most effective anti-poverty programs in the nation. The EITC, an annual tax benefit, allows workers to keep more of what they earn, catch up on bills, and offset some of the costs necessary to go to work, such as transportation and childcare. The longer-term impacts are even more striking, including improved maternal and infant health and increased educational achievement for children, who see higher future earning power as adults.[22] Having affordable housing would likely be even more impactful since it infuses households with more cash every month, not just once a year, and because its average maximum value is far greater than that of the EITC.

Throughout the 1970s, both the Nixon Administration and the Canadian government piloted negative income tax programs that guaranteed monetary assistance to families with children. Analysis of the experiments found that the extra income had positive effects on health, homeownership, and child well-being. Participants in the Canadian experiment used the additional funds for employment training, transportation, and other needs and services that improved their quality of life.[23]

The bullets below describe in greater detail the opportunities that would be available to low-income families if they were to only pay 30 percent of their incomes on rent.

Affordable rents would:

Improve Family Outcomes. A multi-site, rigorous evaluation found that families that received housing vouchers were 52 percent less likely to live in overcrowded housing, 74 percent less likely to become homeless, and moved about 35 percent less often than otherwise-similar low-income families that didn’t receive housing assistance.[24] Studies have shown that families in affordable housing dedicate more than twice as much of their income to health care and insurance, while cost-burdened adults are likely to forgo preventative medical appointments, filling prescriptions, and/or adhering to health care treatments due to cost.[25] Preventive care allows families to improve the quality and length of life and alleviate pressure on public health systems.

Researchers have also found that low-income families that receive housing vouchers spend more on food than low-income families who do not receive housing vouchers. One study found that children in subsidized housing had a 28 percent lower risk of being seriously underweight than children in families waitlisted for subsidized housing.[26] Housing affordability and food spending are inextricably linked, and access to adequate nutritious food plays a significant role in children’s health outcomes, engagement in school, and academic performance.[27]

Further, over a quarter of District households under 50 percent AMI have no access to the internet which makes it more difficult and time-consuming to apply for jobs, help children with homework, make doctor’s appointments, pay utility bills, and perform numerous other daily tasks. People with the lowest incomes are most likely to cite cost as the main barrier to having internet access at home, according to national research.[28] Internet access helps children utilize online research tools, easily collaborate on team projects, and acquire technical and digital skills that are critical for competitive colleges and high-quality jobs.

Stabilize Housing. The most direct impact of this cash infusion is the lower risk of housing instability and homelessness. A Joint Center for Housing Studies analysis found that 11 percent of renters earning less than half of AMI missed at least one rent payment in the previous three months, which can eventually lead to evictions and moves to lower quality neighborhoods.[29] Young children who are forced to move frequently perform worse than their peers on measures of behavioral school readiness and are nearly 20 percent less likely to graduate high school.[30] Extra income would allow households to more easily keep up with rent payments and avoid moves, avoid “doubling up” with friends or relatives, invest in quality childcare, and otherwise support their children’s needs. By remaining in their neighborhoods, families can develop a greater sense of stability and stronger ties to the community.

Create a Stronger Economy. Because Wards 7 and 8—the two wards east of the river—have the highest percentage of households (55 percent and 63 percent, respectively) paying over 30 percent of their income on housing, freed-up income would disproportionately go to families living east of the Anacostia River—most of whom are Black.[31] Additional income for families in Wards 7 and 8 would boost racial equity and create stronger neighborhood economies where small businesses could thrive.

Research demonstrates that low-earners are far more likely to spend the bulk of any extra income leftover after paying necessities because they have less disposable income while high-earners are more likely to save it since most of their needs are already met.[32],[33] Creating economic growth at lower income levels would likely contribute to a positive cycle of increased aggregate spending, higher employment levels, and a stronger economy.

Steps for Creating a Thriving DC

The District should invest in safe and affordable housing for its lowest earners by taking the following steps. While these are not comprehensive, they would help advance the goal of expanding affordability:

Invest adequately in all of the District’s complementary housing tools to better serve extremely low-income households. More specifically, invest at least $250 million in the HPTF to help build and preserve affordable housing. In order to meet the new requirement that 50 percent of the funds serve extremely low-income households, invest in the Local Rent Supplement Program (LRSP) at a proportionately high rate to help cover the difference between rents that low-income families can pay and the rents they face. At the same time, the District should continue to invest in the Affordable Housing Preservation Fund to aggressively preserve existing affordable housing at risk of being lost.

Ensure no deeply affordable housing units are lost during the District of Columbia Housing Authority’s (DCHA) “repositioning” plan. Public housing is a key source of stable, affordable housing for thousands of the District’s extremely low-income families. DCHA recently released a plan to renovate or replace part of its public housing stock because many properties are in poor, uninhabitable conditions.[34] While the housing units unquestionably need to be renovated, redevelopment carries risks that residents will be displaced from their community.

One of DCHA’s approaches to use new funding streams and transition properties out of the public housing program—demolition and disposition—could create a net decline in the number of rental assistance units available.[35] District leaders should enforce current residents’ ability and right to return after repairs by replacing each torn-down unit with one of equivalent size in the footprint of the original property, at minimum. Further, new private owners and/or managers at the redeveloped properties must not be able to use more stringent screening criteria than DCHA’s practices.

Invest in deeply affordable housing units for larger families. Large, low-income households face even greater issues finding affordable housing. There are over 11,600 large renter households making under 50 percent AMI, and of those, three-quarters are housing cost-burdened and over one-third are under-housed.[36] The District should increase rental subsidies for extremely low-income large households to make the existing housing stock more affordable. At the same time, the District’s land use policies should incentivize developers to create more affordable large units.

Update zoning to accommodate denser development near high-opportunity, transit areas. Affordable housing development is expensive, especially in high-opportunity areas, but one way to make it more affordable is by encouraging the development of more homes of different types and sizes. This should be paired with additional LRSP funding to help households pay the difference between what they can afford and the cost of the unit. This should also be implemented in conjunction with other policies that protect existing, low-income residents from indirect residential displacement, such as rent stabilization and property tax assistance.

Expand and strengthen rent control. The District’s rent control laws are set to expire in 2020. A coalition of housing advocates have suggested a number of improvements to cap rent increases, expand the number of units subject to rent control, and eliminate loopholes for landlords.[37]

Conclusion

Addressing the needs of the District’s lowest-income residents requires coordination and partnership between District policymakers, nonprofit and for-profit developers, local agencies, and lenders, among others. Just this past year, the District affirmed that displacement and affordable housing are top priorities in the city’s land use decisions and set a goal to add 12,000 new affordable homes throughout the District.[38] But there’s much more to do.

If the District hopes to keep lower-income Black and Brown residents in the District and allow their communities to fully thrive, DC policymakers must ensure that no family spends the bulk of their income on shelter alone. Implementing this would admittedly be a costly venture; but the social and economic returns on guaranteed affordability for all District families are arguably much higher.

[1] HUD User. Defining Housing Affordability. Households spending over 30 percent of their income on housing and utilities are considered “cost-burdened”. Households spending over 50 percent of their income on housing and utilities are considered “severely cost-burdened”.

[2] This analysis largely excludes people experiencing homelessness, as well as households with zero or negative income. The data source for this analysis, the American Community Survey (ACS), only surveys residents in fixed addresses, thereby excluding individuals living on the street. People living in “group quarters”, such as homeless shelters and nursing facilities, are also excluded because of the small sample size and unreliability of estimates. This report analyzes ACS “household” data (not “family”), and a household technically consists of all the people who occupy a housing unit, including both related family member and unrelated people such as lodgers and wards. That said, although “family” and “household” data are not interchangeable in see DC’s ‘Maximum Income, Rent and Purchase Price Schedule’ for the annual incomes associated with these AMI levels.

[3] Kilolo Kijakazi, Rachel Marie Brooks Atkins, Mark Paul, Anne Price, Darrick Hamilton, and William A. Darity Jr. The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital, Urban Institute, November 1, 2016.

[4] Affordable Housing: Put DC on a Path to Fully Meet the Housing Needs of Extremely Low-Income Renters, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, January 31, 2019.

[5] Yasna Khademian, “One Fifth Of Ward 7 And 8 Residents Believe Housing Costs Will Force Them To Move In The Next Three Years,” DCist, July 15, 2019.

[6] Jason Richardson, Bruce Mitchell, and Juan Franco. Shifting Neighborhoods: Gentrification and cultural displacement in American cities. National Community Reinvestment Coalition, March 19, 2019.

[7] National Low Income Housing Coalition. Study Finds Severely Housing Cost-Burdened Households Experience Greater Food Insecurity, More Child Poverty, and Worse Health Outcomes, March 25, 2019.

[8] Dwyer Gunn. “Low-Income Americans Face A Harrowing Choice: Food or Housing,” Pacific Standard, November 2, 2018.

[9] Comprehensive Plan Housing Element – Draft Amendments. DC Office of Planning, October 2019.

[10] The median household size for the District’s extremely low-income population is 1.8, and there are 39,500 rental households earning 30 percent AMI or less. Capital One Arena holds 20,656 people compared to approximately 71,100 extremely low-income individuals in rental households.

[11] Claire Zippel. Building the Foundation: A Blueprint for Creating Affordable Housing for DC’s Lowest-Income Residents. DC Fiscal Policy Institute, April 4, 2018.

[12] Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development (DMPED), DC Economic Strategy.

[13] Claire Zippel. How to Build Affordable Housing Without an Expiration Date, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, September 12, 2016.

[14] Elizabeth La Jeunesse, Alexander Hermann, Daniel McCue, and Jonathan Spader, Documenting the Long-Run Decline in Low-Cost Rental Units in the US by State, September 2019.

[15] Claire Zippel. A Broken Foundation: Affordable Housing Crisis Threatens DC’s Lowest-Income Residents. DC Fiscal Policy Institute, December 2016.

[16] Doni Crawford. To Ensure all Residents Have a Safe and Affordable Place to Call Home, DC Needs to Double Down on the Housing Production Trust Fund, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, March 10, 2019.

[17] Susanna Groves and John MacNeil with Anne Phelps and Joseph Wolfe. Economic and Policy Impact Statement: Approaches and Strategies for Providing a Minimum Income in the District of Columbia. DC Council Budget Office, February 2018.

[18] DC Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD), the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, and the Poverty and Race Research Action Council (PRRAC). Draft for Public Comment: Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice, September 2019.

[19] The area median income (AMI) is the income for the middle household in the DC region, which includes not only DC but the suburbs. Currently, households in the Washington region making 100 percent of the AMI make $121,300 for a family of four.

[20] DDOT’s FY 2020 approved operating budget is $146,657,822 (CFO) and CFSA’s FY 2020 approved operating budget is $220,273,172 (CFO).

[21] Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, Arloc Sherman, and Brandon Debot. EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds. Center on Budget & Policy Priorities, October 1, 2015.

[22] Center for Law and Social Policy. Research Shows Long-Lasting Benefits of EITC, October 2017.

[23] Susanna Groves and John MacNeil with Anne Phelps and Joseph Wolfe. Economic and Policy Impact Statement: Approaches and Strategies for Providing a Minimum Income in the District of Columbia. DC Council Budget Office, February 2018.

[24] Arloc Sherman and Tazra Mitchell, Economic Security Programs Help Low-Income Children Succeed Over Long Term, Many Studies Find. Center of Budget and Policy Priorities, July 2017.

[25] Enterprise Community Partners. Impact of Affordable Housing on Families and Communities: A Review of the Evidence Base (p. 7), 2014.

[26] Alan F. Meyers et al., Rx for Hunger: Affordable Housing. Children’s HealthWatch and Medical-Legal Partnership, December 3, 2009.

[27] Joydeep Roy, Melissa Maynard, and Elaine Weiss. The Hidden Costs of the Housing Crisis (p. 7). Partnership for America’s Economic Success, 2008.

[28] Office of Policy Development and Research (PD&R), “Digital Inequality and Low-Income Households,” Fall 2016, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/fall16/highlight2.html.

[29] Joint Center for Housing Studies. The State of the Nation’s Housing 2016 (p. 32), June 22, 2016.

[30] Joydeep Roy, Melissa Maynard, and Elaine Weiss. The Hidden Costs of the Housing Crisis (p. 1). Partnership for America’s Economic Success, 2008.

[31] Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development (DMPED), DC Economic Strategy.

[32] Stephen Koukoulas, “Economic growth more likely when wealth distributed to poor instead of rich,” The Guardian, June 3, 2015.

[33] Elizabeth Currid-Halkett. The Sum of Small Things: A Theory of the Aspirational Class (p. 39). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017. Print.

[34] Morgan Baskin, “As DC Weighs How to Fix Its Public Housing, Families Keep Getting Sicker”. Washington City Paper, March 2019.

[35] Will Fischer. The Future of Public Housing: Background on Existing Policies. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 2019.

[36] Peter A. Tatian, Leah Hendey, and Scott Bruton. An Assessment of the Need for Large Units in the District of Columbia. Urban Institute and Coalition for Nonprofit Housing & Economic Development, June 2019.

[37] Marissa J. Lang, “Housing advocates push for more aggressive rent-control measures in DC.” The Washington Post, October 2019.

[38] Office of the Mayor. Mayor Bowser Makes Washington, DC the First City in the Nation to Set Affordable Housing Goals by Neighborhood, October 2019.