Summary:

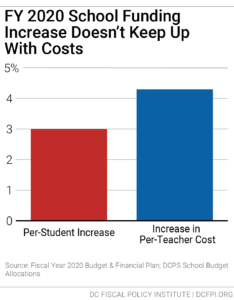

- 3% increase in per-student funding, less than increased per-teacher expenses.

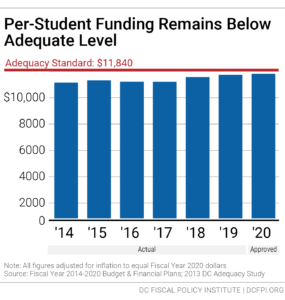

- Base funding per student ($10,980) is $860 below amount recommended in 2013 Adequacy Study.

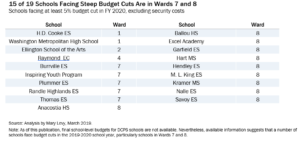

- Budget cuts at many DCPS schools, disproportionately impacting schools in Wards 7 and 8.

- A large share of DCPS at-risk funds diverted from intended purpose to supplement supports for low-income students.

- $9 million increase will add mental health staff to 107 schools.

- Funding to implement “The Student Fair Access to School Act,” which helps schools replace punitive school discipline with positive behavioral supports.

- $1.6 million to expand Community Schools model, which builds partnerships to address neighborhood needs, to 6 additional schools.

The fiscal year (FY) 2020 budget for schools fails to keep up with the rising costs of education, and in several ways represents a backward step in addressing educational inequities in the District of Columbia. Under the budget, per-student funding increases less than the average cost of a DC Public School teacher (Figure 1). That means that overall, schools will face challenges maintaining current staff and services.

The budget particularly shortchanges students of color in low-income communities by not providing resources needed to address historic inequities in education access. The budget doesn’t implement recommendations of a recent working group on school finance, sponsored by DC government, which called for increasing funding for “at-risk” students and English language learners (ELL) to an adequate level over a four-year period. Beyond that, DC Public Schools (DCPS) will continue to inappropriately divert half of its at-risk funds intended for high-poverty schools to other purposes. And while final school-level budgets for DCPS are not available as of this writing, it appears that many schools in Wards 7 and 8 face budget cuts, a result of falling enrollment and problems in the way DCPS allocates resources to schools, among other factors.

The budget includes $9 million to add mental health staff to about 107 schools, following recommendations of a School-Based Mental Health task force. This funding is sufficient to allow the provisions of the Student Fair Access to School Act to go into effect, which is intended to reduce reliance on punitive school discipline. The budget doesn’t, however, provide mental health staff at the level recommended by advocacy groups.[1]

The budget also adds funding to expand the Community School model, intended to serve the “whole child,” to six more schools.

Figure 1.

Inadequate School Funding Increase Creates Problems at Many Schools

The general fund budget for DCPS for FY 2020 is $918 million, an increase of 4.5 percent over FY 2019, adjusting for inflation. The FY 2020 budget for public charter schools is $905 million, a 0.6 percent reduction, adjusting for inflation.

School funding starts with a base amount per student, which varies by grade. Schools receive additional resources for students who are English Language Learners, special education students, or students at risk of academic failure. The school funding formula—known as the Uniform Per Student Funding Formula (UPSFF)—applies both to DCPS and public charter schools.

The FY 2020 budget increases the UPSFF base by 3 percent, from $10,658 to $10,980 per-student.

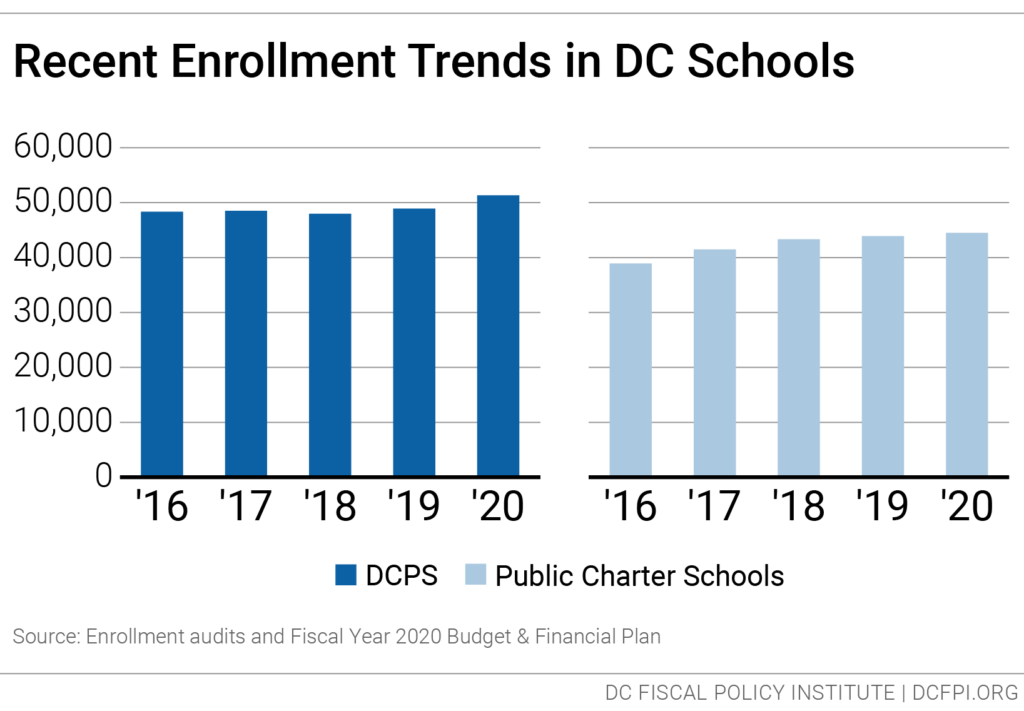

Enrollment is expected to grow in DCPS and remain essentially flat in public charter schools in the next school year, with an expected combined enrollment of about 96,000 students (Figure 2).

The increase in the DCPS budget reflects the growing enrollment and expected increases in the number of special education students and English language learners. The funding decrease for public charter schools reflects small reductions in the number of students in special education, English language learners, and “at-risk” students.

Figure 2.

School Funding Is Inadequate Using Several Measures

Under the FY 2020 budget, schools will face a loss of purchasing power. The 3 percent increase in the UPSFF is more than the expected rate of inflation—2.3 percent—but less than the cost increase for key education cost drivers. For example, DCPS school budget allocation documents show that the average expenses per teacher will grow over 4 percent next year[2] (Figure 1, pg. 1). This means schools won’t have enough resources to maintain all staffing and services. (As noted below, the budgets will be cut for many individual DC Public Schools, especially in low-income communities.)

Beyond that, per-student school funding remains well below the amount identified in a 2013 DC Education Adequacy Study commissioned by the DC government.[3] That study recommended a base rate of $11,840 per-student, when adjusted for inflation to FY 2020 dollars—which means the $10,980 level for FY 2020 is $860 lower than the level considered adequate (Figure 3).

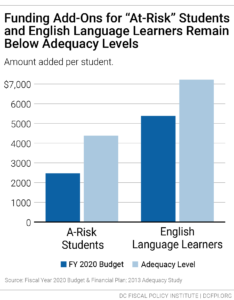

Finally, the supplemental funding provided for students who are “at-risk” and for English language learners remain well below the level called for in the 2013 Adequacy Study, despite recent recommendations to increase them. The current school funding formula provides an additional $2,470 for every “at-risk” student, but this is 44 percent below the recommended level. The funding formula provides an added $5,380 for each English language learner, or 26 percent below the recommended level. A February 2019 report from a working group of the Office of the State Superintendent of Education recommended bringing both amounts to the full level identified in the Adequacy study over the next four years, but the approved budget included no increases[4] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Many Schools East of the River Are Likely to See Budget Cuts

As of this publication, final school-level budgets for DCPS schools are not available. Nevertheless, available information suggests that a number of schools face budget cuts in the 2019-2020 school year, particularly schools in Wards 7 and 8.

DCPS published school-level information that reflect budgets proposed by the Chancellor that were then modified through input from each school’s Local School Advisory Team (LSAT) and between school leaders and DCPS central office, during the spring of 2019. These school-level budgets do not, however, reflect any shifts of funds made by DCPS over the summer of 2019 or $5.3 million in funds the DC Council added to the Mayor’s budget proposal (during the FY 2020 budget process.[5] DCFPI will update its analysis when this information becomes available.

An analysis of available budget information suggests that many schools face budget cuts this year, particularly schools in Wards 7 and 8. Under the currently available budget information, 30 schools faced budget reductions when security costs are not included, with 19 facing cuts of more than 5 percent. On the other hand, 85 schools saw budget increases, with 53 seeing an increase of 5 percent or more.

As noted, the DC Council added an additional $5.3 million to the DCPS budget, compared to the Mayor’s proposal. The Council directed that all these funds go to schools that had faced cuts in the initial budget allocations. These funds will offset some of the cuts, but it is unlikely they will offset all the cuts. Of those schools facing budget cuts before these funds are considered, the cuts totaled $14 million, which means the added $5.3 million is unlikely to fully restore the cuts.

The schools facing cuts were concentrated heavily east of the Anacostia River. Of the 19 schools with budget cuts of more than 5 percent based on currently available information, 15 are in Ward 7 or Ward 8 (Table 1, pg. 9).

Numerous factors can lead to changes in funding for an individual school, including changes in enrollment or the number of students for whom additional resources are provided, such as special education students. The cuts in the coming year stem at least in part from expected drops in enrollment. Of the 14 schools in Wards 7 and 8 that faced substantial funding cuts in their initial allocations, 7 are projected to see enrollment declines of 5 percent or more. This continues a pattern of recent years. This year, for example, DCPS schools east of the Anacostia River were projected to lose 10 students for every student gained west of the river.[6]

Under DCPS school allocation rules, schools receive “stabilization funds” to ensure that their funding doesn’t drop substantially from year to year, but this process doesn’t work well to protect schools, especially in the coming year. [7] For example, a school that faces a large drop in funding for core staffing due to an enrollment decline may not receive any stabilization funds if it receives an increase in specialized funds, such as for special education.

For the coming year, DCPS included security costs in local school budgets for the first time, which inflated FY 2020 budgets for schools when comparing them to FY 2019 budgets and reducing the amount of stabilization funds schools received.

For example, imagine a school with a $1 million budget in FY 2019—when security costs were not factored into school budgets—and a $1 million budget in FY 2020 that includes $100,000 for security. Funding for that school outside of security would be a 10 percent decline, yet counting security in the FY 2020 budget would make it look as if the school’s budget isn’t falling and that the school doesn’t need stabilization funds. By adding security costs for the coming year and then comparing with the current-year budget that doesn’t include security, it means that fewer schools with declining enrollment qualify for stabilization funds.

While there is some logic to reducing school budgets when enrollment falls, the resulting staffing and service cuts can compound the challenges that led to declining enrollment. This can put schools that need help in a weaker position, making further enrollment declines more likely. Beyond that, the fact that the largest budget cuts are concentrated in Ward 7 and Ward 8 suggests that as a matter of equity, DCPS needs to do more to invest in these schools, rather than allowing their budgets to fall.

Limited School Funding Leads to Misuse of At-Risk Money

Both DCPS schools and public charter schools will receive an additional $2,470 per student in FY 2020 for low-income students and other students at risk of falling behind academically. “At-risk” students are those who are in foster care, experiencing homelessness, overage for their grade, or participate in SNAP or TANF.[8]

At-risk funds are intended to give low-income students the same enriching opportunities as their higher-income peers and ensure that students struggling academically get targeted supports. By law, 90 percent ($2,223) of at-risk funds must follow the student to their DCPS school.

In the coming year, DCPS is projected to serve 25,200 “at-risk” students and public charters are projected to serve 18,400. This represents about half of students in publicly funded DC schools. Total at-risk funding for FY 2020 is $106 million.

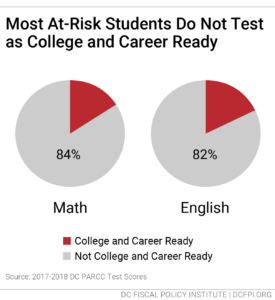

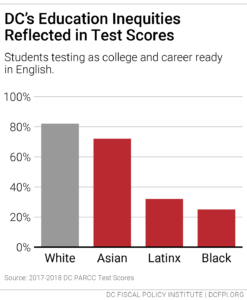

The need for at-risk funds to support educational equity is clear. Just 16 percent of “at-risk” students in DC are college and career ready in math and 21 percent are college and career ready in English, according to test scores (Figure 5). Some 85 percent of white students are considered college and career ready in English, compared with 28 percent of Black students and 37 percent of Latinx students (Figure 6).[9] These differences reflect historic barriers to academic success that continue to marginalize students of color.

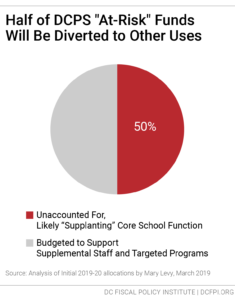

DCPS use of at-risk funds is not fully reaching the intended students. In the proposed FY 2020 budget for DCPS, roughly half of the dedicated at-risk funds were directed to pay for core classroom staff instead of supporting additional, targeted resources, such as evening credit recovery, according to an analysis by school budget expert Mary Levy[10] (Figure 7). (There is not sufficient information yet to do this analysis for the approved FY 2020 budget.)

The DC Auditor also has found that DCPS has used at-risk funds to supplant core education staffing, which means that the funds cannot be used as a supplement. In a 2017 study of eight DCPS elementary schools, the Auditor revealed that at-risk funds were used for positions that all schools receive under basic staffing standards in at least four schools.[11] A 2019 update by the DC Auditor showed that at-risk funds are often used to cover the cost of librarians, positions that all schools are supposed to receive as part of the basic staffing model. The Auditor found that the schools with the largest share of students who are “at-risk” had the greatest likelihood of having librarians paid for using these funds.[12]

The use of at-risk funds to pay for basic staff positions appears to stem from tight school budgets overall that leave inadequate resources to cover core staffing needs. More adequate base funding would allow schools to address basic needs without having to tap at-risk funds. As noted, the base funding in DC schools is $1,000 lower per-student than the amount deemed adequate in DC’s 2013 Adequacy Study.

Because there is no standard staffing requirements in public charter schools, it is not easy to determine how at-risk funds are used to supplement services. Although the DC Public Charter School Board publishes a report on how schools spent their at-risk dollars in the prior year, families often do not have information on how these dollars are budgeted for the next year.[13]

Legislation introduced in the DC Council in 2019 would increase the transparency of at-risk funds in both DCPS and public charter schools.[14] It also is intended to empower parents, teachers, and other school stakeholders to have a say in how at-risk funds are used in their school. School leaders and LSATs in DCPS are expected to play a role in shaping their school’s budget each year, but the lack of transparency often does not allow them to engage in meaningful discussions over how to use these funds to improve student outcomes.

Budget Maintains Out-of-School Time Programs, But More is Needed

The FY 2020 budget largely maintains substantial increases adopted in FY 2019 for the Office of Out-of-School Time (OST) Grants and Youth Outcomes and seasonal camps for the Department of Parks and Recreation. It includes a total of $18.5 million for Out-of-School Time learning in these two agencies, compared with $19.6 million in FY 2019.

OST programs expose students to arts, athletics, technology and applied science, with demonstrated payoffs in classroom performance.[15] OST opportunities improve academic, social, and health outcomes, and give parents peace of mind knowing their children are in a safe environment while they work. After-school programs reduce how often parents miss work, and summer programs limit summer learning loss.[16]

Further increases are needed to enable the students who need it most to have the same kind of enriching Out-of-School-Time opportunities as their higher-income peers. Future investments should be guided by the Commission on OST Grants and Youth Outcomes that is working to advance better access to quality OST programming across the city.

Budget Expands School-Based Mental Health Programs

The FY 2020 budget includes $9 million to improve and expand services for the Department of Behavioral Health (DBH) School Mental Health Program (SMHP), following recommendations of the Task Force on School Mental Health.[17] Much of the new funding will be awarded to community-based behavioral health providers, which will support clinicians and clinical supervisors in an estimated 107 additional schools. They will engage in parent and teacher consultation, school team meetings, care coordination, and crisis management.

The added funding in the FY 2020 budget is sufficient to implement the 2018 Student Fair Access to School Act,[18] which steers schools away from exclusionary school discipline practices that disproportionately hurt students of color and special education students. The provisions go into effect for elementary school students in the 2019-2020 school year, and for middle and high school students in the 2020-2021 school year. (The legislation initially was intended to go into effect for middle schools in 2019-2020, but the budget delayed it by one year.)

When schools rely on exclusionary discipline, students miss lessons, fall behind upon return, and are more likely to drop out.[19] Beyond that, suspension and expulsion have been applied in DC in a discriminatory way. Black students are 7.7 times more likely to be suspended and sent out of the classroom than their white peers.[20] Students with disabilities are over twice as likely to be suspended as students without disabilities.[21]

The Student Fair Access to School Act aims to give schools the resources to fully staff promising solutions like Restorative Justice that better address the root causes of disruptive behavior. Under this approach, students acquire the skills to manage their emotions and actions, learn to take responsibility for their mistakes, develop a greater sense of empathy, strengthen relationships, and repair harm. Teachers are better supported in managing the classroom without interrupting the learning of individual students.

The Student Fair Access to School bill requires funding to train school-level staff in how to address behavior issues of students facing trauma, and to hire school-level staff to provide positive interventions.[22]

While the FY 2020 budget provides the funding needed to implement these provisions, it is likely that even more will be needed provide an adequate number of school-level staff. One education advocacy effort sought $54 million in total funding in the FY 2020 budget for mental health supports and trauma-informed training, covering services related both to the Student Fair Access to School Act and the School-Based Mental Health program.[23]

New Dollars for Community Schools

The budget increases funding by $1.6 million for Community Schools, bringing total funding to $4.4 million. The new schools are Anacostia, Ballou and Cardozo high schools; Eliot Hine and Sousa middle schools; and Langley Elementary School. Under DC’s Community Schools model, each school qualifies for about $200,000 to hire a coordinator and provide services.[24]

The Community Schools model recognizes that schools are not just centers of academic instruction. Community schools can be neighborhood hubs that partner with community-based organizations to connect children and their families with health care, afterschool programs, adult education, early childhood programming, and other services. Consolidating school and essential services into one building helps children from low-income families by removing barriers to accessing services and resources, reducing absenteeism, improving academic performance, and building trust among students, parents, and faculty.[25]

Table 1.

[1] The #DoMorewith54 campaign called for $54 million in funding for these services.

[2] According to budget allocations at the school level, the average expenses associated with a teacher will rise from $104,600 in FY 2019 to $109,100 in FY 2020. The average cost per teacher figure is shown in individual school budget allocation sheets.

[3] Deputy Mayor for Education. (2013) “Cost of Student Achievement: Report of the DC Education Adequacy Study.”

[4] “OSSE’s Report on the Uniform Per Student Funding Formula,” DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, January 2019.

[5] In a phone call with DCFPI staff on October 4, 2019, DCPS Budget Director Allen Francois noted that the submitted school-level budgets on the DCPS website do not reflect funds added by the DC Council or summer 2019 reprogrammings, DCPS hopes to post school-level “submitted adjusted” budgets in the fall of 2019 to reflect these changes.

[6] See DCFPI, “What’s in the Approved Fiscal 2019 Budget for PreK-12 Education,” August 2, 2018.

[7] “The Fair Student Funding and School Based Budgeting Act of 2013 provided that no school could lose more than 5% of its budget between fiscal years. If a school’s allocation would mean it would lose more than 5% of its budget between one year to the next DCPS allocates additional stabilization funds.” “Definitions”, C4DC School Budget Tool.

[8] SNAP stands for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as food stamps. TANF stands for or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

[9] These are scores in English Language Arts, from 2019 DC Statewide Assessment Results, Office of the State Superintendent of Education.

[10] Analysis by Mary Levy, March 2019.

[11] McCrae, Candace. (2017) Office of the District of Columbia Auditor, “Budgeting and Staffing at Eight DCPS Elementary Schools.”

[12] See Statement by the Hon. Kathleen Patterson, D.C. Auditor, To Be Included in the Record for the Joint Oversight Roundtable on At-Risk Funding Transparency Held Friday, February 1, 2019, by the Council of the District of Columbia Committee of the Whole and the Committee on Education (Updated 2/22/19).

[13] “FY 2017 report on the use of at-risk funding in DC public charter schools,” DC Public Charter School Board, February 2018.

[14] See proposed At-Risk Transparency School Funding Amendment Act of 2019.

[15] DCAYA, “#ExpandLearning DC”, June 2016.

[16] Karl Alexander et. al, (2007) “Lasting Consequence of the Summer Learning Gap”. “Community, Families & Work Program Parental After-School Stress Project”, (2004) Brandeis University.

[17] See “Report of the Task Force on School Mental Health,” March 26, 2018.

[18] Council of the District of Columbia, “B22-0594 – Student Fair Access to School Act of 2017.”

[19] Office of the State Superintendent for Education “State of Discipline: 2016 – 2017 School Year.”

[20] Office of the State Superintendent for Education “State of Discipline: 2016 – 2017 School Year”, p. 29.

[21] Calculation by Children’s Law Center based on data from OSSE (2017). State of Discipline: 2016 – 2017 School Year”, p. 34.

[22] The legislation requires another $8 million in FY 2020 to enact the provisions scheduled for school year 2020. “B22—0594 Student Fair Access to School Act of 2017”; Fiscal Impact Statement-Student Fair Access to School Amendment Act of 2018

[23] The advocacy campaign around the FY 2020 budget is called #DoMorewith54.

[24] Office of the State Superintendent for Education, “Community Schools Incentive Initiative Grantees 2018.”

[25] Anna Maier, Julia Daniel, Jeannie Oakes, and Livia Lam, “Community Schools as an Effective School Improvement Strategy: A Review of the Evidence,” Learning Policy Institute, Dec 2017.