Chairman McDuffie and other members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today. My name is Kate Coventry, and I am the Senior Policy Analyst of the DC Fiscal Policy Institute. DCFPI is a non-profit organization that promotes budget choices to address DC’s economic and racial inequities and to build widespread prosperity in the District of Columbia, through independent research and policy recommendations.

I’m here today to support Act 22-0608, the Public Restroom Facilities Installation and Promotion Act of 2018 and to urge the Council to fund the Act in the fiscal year (FY) 2020 budget. I’m also here to urge the Council to find additional funding for housing and services for residents experiencing chronic homelessness.

Public Restroom Facilities Installation and Promotion Act

Passed unanimously by the Council in late 2018, the Public Restroom Facilities Installation and Promotion Act creates a working group to develop a two-pronged approach to promote restroom access: creating stand-alone restrooms and incentivizing businesses to allow the public to use their restrooms. As a member of the working group, the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development has an important role to play in implementing this Act.

Public restrooms are fundamental to human dignity and human health. They are especially critical for people who are restroom-challenged. When seniors, pregnant women, young children, and people on certain medications have to go, they have to go urgently. Easily accessible, clean, safe restrooms make good business sense and help foster tourism. Knowing that there are public restrooms readily accessible, people are more apt to visit parks, ride their bikes, jog, and walk. As a result, more and more cities are investing in public restrooms.

Residents experiencing homelessness are also particularly affected. Almost all shelters are closed during the day, so residents cannot access the restrooms there. And there is evidence that fewer businesses are allowing non-customers to use their restrooms: the People for Fairness Coalition (PFFC) visited 85 businesses in five areas of DC that have high levels of pedestrian traffic and people experiencing homelessness to see if they would allow the general public to access their restrooms. In 2015, they found that 43, just over half of the businesses, allowed anyone to use their restroom. In 2016, they visited these businesses again and found that only 28 allowed access to individuals who weren’t customers. In 2017, they visited these businesses again and found that only 11 still allowed this access. They also found, in their 2016 follow up, that businesses discriminated against a PFFC member experiencing homelessness who visited the restrooms. Most residents experiencing homelessness do not have money to make purchases at these establishments in order to be able to gain access to the restroom.

The lack of access to bathrooms is not merely an inconvenience—it can have devastating health and public health consequences. Dr. Catherine Crossland of Unity Healthcare testified last year about her patients skipping lifesaving blood pressure, heart and HIV/AIDS medications because they can lead to an urgent need for the restroom. Southern California is experiencing the largest Hepatitis A outbreak since the 1990s because of the lack of toilets and handwashing facilities for residents experiencing homelessness. At least 20 people have died as a result.

The working group will identify sites with limited access to restrooms that would be appropriate to install a stand-alone bathroom model that is available 24/7, such as the Portland Loo.

The Loo is a prefabricated structure that takes up an area the size of a parking place. The Loo was designed in Portland in 2007 by an architect, business owners, and community members aiming to maximize safety both inside and out by applying Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design principles and ensuring that it be economical and easy to maintain. Selecting an appropriate location for the Loo is very important for ensuring safety. It should be in an area that is visible from a distance and where there is a high level of pedestrian and vehicular traffic. For a Loo to be successful in a given location, it must be in an open visible area and there must be support and monitoring from the surrounding community, such as businesses, Advisory Neighborhood Commissions (ANCs), and neighborhood associations.

Crime prevention features include angled shutters along the bottom and above the eye level that protect privacy while ensuring that one can see how many people are inside. The restroom has an anti-graffiti coating and has lighting outside at night. To minimize installation costs, the site should be near water and sewer connections.

The safety, crime, and cleanliness measures combined with the fact that the Loo is relatively economical to install and maintain, has made it the stand-alone public restroom of choice in over 23 cities in the United States and Canada, including Portland, Oregon; Seattle, Washington; Greeley, Colorado; Salt Lake City, Utah; Cambridge, Massachusetts; and Victoria, British Colombia.

While visiting Portland, I was able to use the Loo. Visible from several blocks away, the unit was cleaner than most department-store bathrooms and felt very safe as there was significant pedestrian traffic. When I was as an au pair in Switzerland, I appreciated that almost every town had a bathroom located in the train station or city hall. This greatly reduced my anxiety about traveling with a small child who had just begun potty training.

By increasing access to public restrooms, the District can be a friendlier place for tourists, children and their caretakers, residents with illnesses and disabilities, and residents experiencing homelessness. I urge the Council to fund the Public Restroom Facilities Installation and Promotion Act of 2018 in the FY 2020.

Additional Investments Needed for Residents Experiencing Chronic Homelessness

Residents experiencing chronic homelessness have been homeless for a long time and suffer from significant physical and/or mental health issues. For these residents, housing is health care and can often make the difference between life and death. People who don’t know where they’re going to spend the night struggle to receive needed services like medical treatment or counseling. And they are often forced to stay in places that are unsafe or make their illnesses worse. As a result, the life expectancy of people facing chronic homelessness is far shorter than for those who are stably housed.

The Mayor’s FY 2020 budget includes $8.8 million to end chronic homelessness for 325 individuals through Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH), a proven and life-saving housing intervention that combines long-term affordable housing with intensive wraparound services. This is 24 fewer units than included in the FY 2019 budget and falls far short of the investments needed to end homelessness for those most at risk of dying on the streets or in shelter. While a step in the right direction, the proposed funding meets just 33 percent of The Way Home campaign’s recommendations and only 20 percent of the overall need, leaving 1,319 individuals in urgent need of PSH.

The budget includes just $420,070 to end chronic homelessness for 20 individuals through Targeted Affordable Housing (TAH) which provides long-term affordable housing for individuals who need help paying rent but don’t need the intensives services provide with PSH. This meets just 6.5 percent of the need and only 13 percent of The Way Home campaign’s recommendation. It is also 90 fewer units than were included in the FY 2019 budget.

We urge the DC Council to preserve the current investments in TAH and PSH and invest an additional $18.2 million in PSH to serve 661 individuals and $2.6 million in TAH to serve 134 individuals.

Additionally, there is a critical gap in funding for outreach services which help hard-to-reach individuals experiencing chronic homelessness who are sleeping on the street and suffering from severe health problems that are hard to manage while living outside. Homeless Street Outreach works in a coordinated way to help support some of our most vulnerable neighbors experiencing homelessness by connecting them to housing and other supportive services while also increasing health, safety, and quality of life while people are unsheltered. Over the past three years, DC has used federal funding to pay for street outreach that has ended homelessness for over 325 individuals. A review of studies found that outreach services improve health and housing outcomes.[1]

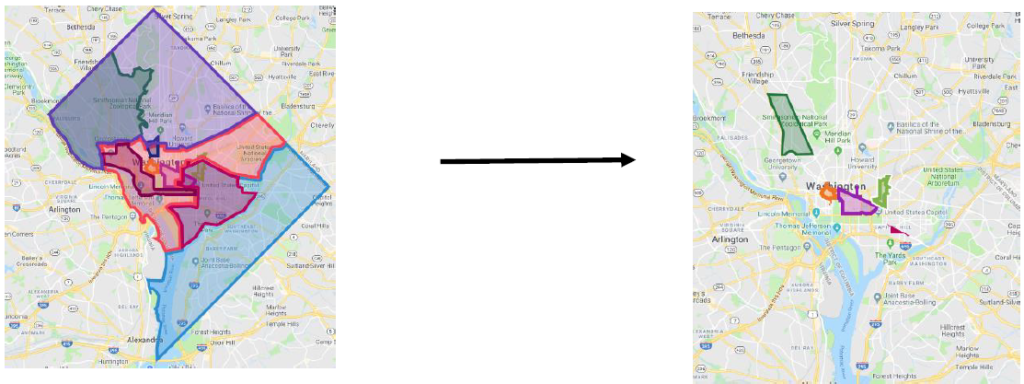

This vital federal funding expires at the end of April. Without sustainable funding for FY 2020 and beyond, current street outreach capacity will decrease by 25 staff people, leaving only 15 dedicated staff and significantly diminishing the supports available to over 600 individuals who are unsheltered. It will also greatly reduce the number of neighborhoods with outreach services (see maps below). We are deeply concerned about how this cut will affect some of our most vulnerable neighbors. Without the assistance provided by professionally trained outreach workers, our businesses and houses of worship struggle to meet the needs of their homeless neighbors. We urge the Council to add $3.5 million in local funds to fill this critical gap in services.

Thank you for the chance to testify and I’m happy to answer any questions.

[1] Jeffrey Olivet, Ellen Bassuk, Emily Elstad, Rachael Kenney and Lauren Jassil. Outreach and Engagement in Homeless Services: A Review of the Literature https://dmh.mo.gov/docs/mentalillness/litreview.pdf