Public housing is a key source of stable, affordable housing for over 7,300 of the District’s extremely low income families, including many in deep poverty. DC’s public housing primarily serves residents who are elderly or have disabilities – many of whom live on very modest fixed incomes. Families with children also count on public housing for a low-cost home, including many who need large apartments (three bedrooms or more) that are hard to find in the private market. Public housing provides strong protections to its tenants, including low rents that adjust to changes in income, unique tenant rights, and resident organizations that have formal input in housing authority decisions.

Unfortunately, public housing – which is owned and operated by the DC Housing Authority, with funding from the federal government – is a resource at risk. Chronic federal underfunding means that most of DC’s public housing properties are in bad shape, and need to be rehabilitated or replaced. Public housing residents need better quality homes. The District should take assertive steps to preserve this important source of low-cost housing.

While public housing redevelopment is needed, it also can carry risks that residents will be displaced from their community or even lose affordable housing during construction, or that they won’t be able to come back when the property reopens. There are steps the DC Housing Authority should take to ensure residents can continue to rely on public housing as a stable, affordable source of housing, and can stay connected to their social support networks during redevelopment. Above all, it’s important that residents have a voice in how redevelopments are planned, and that their rights and needs are first and foremost throughout the process.

This report uses data on occupied public housing units from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2014 Picture of Subsidized Housing dataset.

Who Lives in DC’s Public Housing?

The key groups served by DC’s public housing are seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children. Public housing provides many of the units that are hard or even impossible to find on the private market: affordable apartments with accessible features, or with enough bedrooms for a family with kids.

Public Housing Primarily Serves the Elderly and People with Disabilities

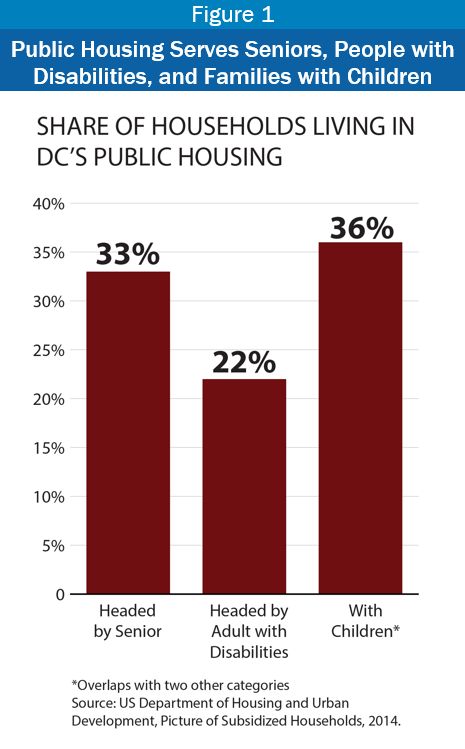

- Seniors and residents with disabilities represent 55 percent of all heads of household in DC’s public housing, a total of 4,000 households (Figure 1).

- One third of households in public housing are headed by an elderly person, half of whom also have a disability. Another fifth of households are headed by a nonelderly person with a disability.

- Fourteen of DC’s 40 public housing properties – which include about one-fourth of all public housing units – are dedicated for seniors and people with disabilities. These properties provide accessible units, often with supportive services onsite or close by.

Families with Children Rely on Public Housing for Affordable Family-Sized Apartments

Over 2,500 families with children rely on public housing, accounting for 35 percent of households in DC’s public housing. Twenty-six percent of public housing units – a total of 1,900 apartments – have three or more bedrooms, with many public housing properties specifically designed to serve families with onsite or nearby recreation facilities and services.

By contrast, larger affordable apartments are rare in the private market, and even in other affordable housing programs.[1] Only 11 percent of all apartments in the District have three or more bedrooms, and only one percent of apartments in DC are low-cost three-bedroom units[2] – and it’s likely that many of those are public housing units. Low-income households with more than two children often struggle to find a place that’s affordable and also has enough bedrooms. Public housing’s larger units thus help limit the extent to which low-income families live in overcrowded conditions. Living in overcrowded housing can contribute to a stressful home environment, which has a negative impact on children.[3]

Public Housing Serves Many Families in Poverty

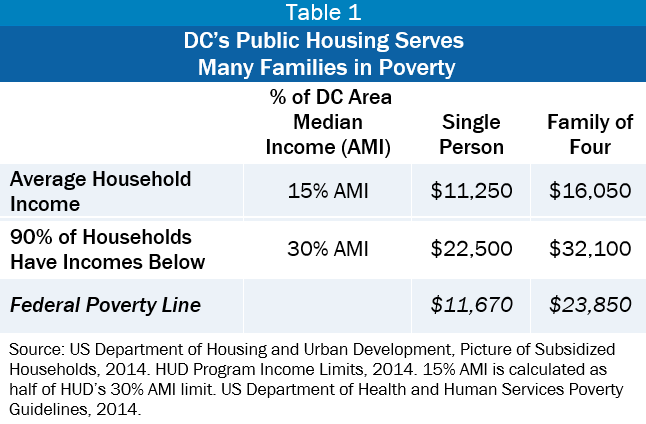

DC’s public housing provides homes to some of the lowest-income households in DC – those that would face the greatest challenges securing housing in the private market. Households living in public housing have incomes averaging 15 percent of the median for the metropolitan area; for a family of four, 15 percent of the median income is only $16,050 a year, $7,800 below the poverty line.

The vast majority of households – 89 percent – have incomes below $32,100 for a family of four, 30 percent of the area median. This means nearly all households living in public housing meet the US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s definition of “extremely low income” (Table 1).

Households in Public Housing Rely on a Range of Income Sources, from Social Security to Wages

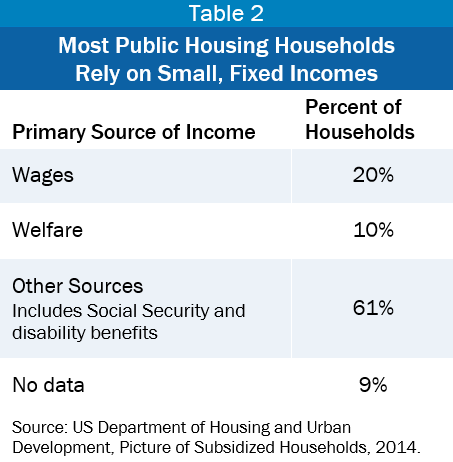

The incomes of DC residents in public housing come from a diverse range of sources, reflecting the diversity of the residents living there. Available data are limited to the share of total households living in public housing whose largest source of income is wages, welfare, or some other source, such as Social Security or disability benefits (Table 2).[4]

- Most households living in public housing rely on small, fixed incomes to get by. Nearly two thirds of households rely on sources other than wages or public assistance as the main source of income.[5] These sources include Social Security retirement or disability benefits, Supplemental Security Income, or pensions. On average, retired workers in the District who rely on Social Security receive $14,820 in annual benefits, just above the poverty line for a single person.[6] For residents with a disability, the average Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) benefit in DC is $12,370 a year, also just above the poverty line for a single person.[7]

- Many public housing households rely primarily on income from work. Wages are the main source of income for 20 percent of families living in public housing. This means that a majority of households in DC’s public housing who do not rely on old age or disability benefits rely on wages.

- Ten percent of families in DC’s public housing rely on public assistance. This is likely to largely reflect families with children receiving TANF cash assistance.

Public Housing Provides Housing Security

Public housing provides an unparalleled level of housing security to households that would otherwise struggle to keep a roof over their head. This is because public housing provides deeply affordable rents that adjust to changes in income, and because residents have unique tenant rights.

Stable, affordable housing is a critical foundation for families’ well-being. Research suggests that having affordable housing allows families to invest more in their children’s development, boosting cognitive achievement.[8] Unaffordable housing costs, in contrast, can make it hard for families to get enough food and to get to work and school, among other challenges. Low-income households in the US who are severely rent burdened – half or more of income goes to pay the rent – spend an average of $145 less on food, $43 less on healthcare, $103 less on transportation, and $24 less on retirement savings each month compared to low-income families who aren’t severely rent burdened.[9]

Public Housing Rents are Affordable to Those Least Able to Pay DC’s Rising Housing Costs

Public housing serves the people least able to afford DC’s high housing costs. The average rent for a household living in public housing is $255, unthinkable in DC’s high cost housing market, where the fair market rent for a studio apartment is over $1,100.[10]

- Rents in public housing are tied to a household’s income. Residents of public housing pay no more than 30 percent of their income for rent. This is far lower than rents typically paid by the District’s extremely low income households. On average, families at this income level spend two-thirds of their income on rent.[11] As the cost of renting in the District rises, public housing and other sources of low-cost apartments are even more critical to ensuring low-income households have an affordable place to live.

- Public housing rents are adjusted when a household’s income fluctuates. The 7,300 households living in public housing can rely on their rent to stay affordable even if income is lost. For instance, if a worker loses a shift at work, they become disabled and lose their job, or they need to stop work to care for a new baby or sick relative, rent is adjusted downward so it doesn’t exceed 30 percent of income. This helps ensure that a change in income doesn’t result in getting behind on rent or evicted.

Unique Tenant Rights Protect Public Housing Resident

Unique tenant rights help make DC’s public housing a secure and stable source of housing for low-income families. All public housing properties also have a resident organization that represents their voice.

- Families in public housing receive a month’s notice before rent is increased, and can contest rent increases through a hearing process. This important protection ensures families aren’t blindsided by an increase in rent, and can take steps to adjust their household budget or contest a rent increase they think has been calculated incorrectly. Contesting a rent increase happens through the grievance process, explained below.

- Families living in public housing can request to move to a different public housing unit or property. For instance, if a resident becomes disabled, they can ask to be moved to an accessible unit. A household with a new baby can request an apartment with more space. The ability of a family to move to a more suitable unit depends on whether there are units available to meet the request, though moves related to safety or domestic violence are expedited.

- A grievance process unique to public housing helps ensures residents’ rights are protected and that the housing authority addresses their concerns. If a resident doesn’t agree with a rent increase, or if their unit hasn’t received necessary repairs, they have the right to present their grievance and have it heard at a meeting with a representative of the DC Housing Authority. If an agreement can’t be reached, an administrative hearing must be held. At the hearing, the resident can present evidence and cross-examine witnesses. The hearing officers can make changes to rent, including retroactive changes; award damages; or order the housing authority to make repairs.

- Residents have formal input in housing authority decisions, from individual properties to agency performance. Resident Councils serve as the point of contact between a property’s residents and the housing authority. Elected by the residents, the Resident Councils organize community events and programs, and the DC Housing Authority provides funding for their operations. A citywide Resident Advisory Board works with the housing authority on overall policy and practices, representing the public housing resident community as a whole. Finally, three residents serve on the DC Housing Authority Board of Commissioners. The Board oversees the agency’s performance, advises it on high-level policy decisions, and appoints the housing authority’s Director.

Funding Shortfalls Have Made It Difficult to Maintain Public Housing

Serious shortfalls in federal funding have limited the DC Housing Authority’s ability to maintain and repair public housing properties, most of which are over 40 years old and need significant capital improvements. The District should develop ways to renovate or replace distressed public housing units, to preserve this critical part of the city’s low-cost housing stock and to improve residents’ quality of life.

Redevelopment also often entails risks for residents. Being displaced from their neighborhood and community during redevelopment, which can take several years, can be harmful to residents who rely on neighbors and service providers for support. Across the country and in the District, when public housing developments have been redeveloped as mixed income communities, replacement of low-cost units often lags behind completion of other units, creating very long waits for families in public housing to return. Some residents may not be able to come back when the property reopens. These risks can be limited through the approaches taken to public housing redevelopment. As described below, the DC Housing Authority should take steps to ensure that public housing remains a stable source of affordable housing for families, seniors, and people with disabilities as the city works to redevelop this aging housing source.

DC’s Public Housing Authority Has Had to Do More with Less

Public housing in the District and across the country has been chronically underfunded by the federal government. Over 6,500 of DC’s public housing units – 78 percent – need significant capital improvements, like new heating and cooling systems, roofs, plumbing, and wiring, at a total estimated cost of $1.3 billion.[12] But last year, the DC Housing Authority received only $14 million for capital improvements from the federal government, and much of that went to filling gaps in the agency’s budget.[13] The DC Housing Authority indicates that in recent years, federal funding has ranged from 83 to 86 percent of what is needed to operate and maintain public housing.[14] As a result, many of DC’s public housing properties have gone without essential maintenance. Some are too deteriorated to fix. For functionally obsolete buildings, replacement is the most cost-effective option.

New Communities Initiative Is a Key Part of DC’s Plans to Redevelop Distressed Public Housing

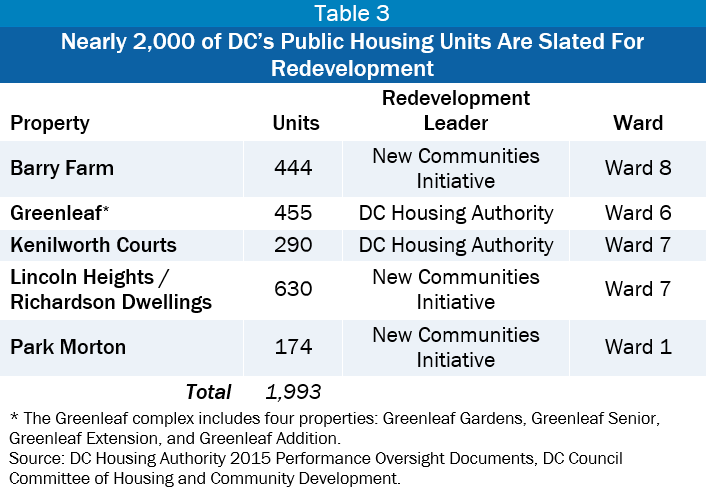

Distressed public housing properties should be rebuilt so that residents have safe, quality apartments. The DC Housing Authority is planning to redevelop five large public housing properties, with approximately 2,000 units in total, into mixed-income developments (Table 3). These properties are Barry Farm (Ward 8), Greenleaf Gardens (Ward 6), Kenilworth Courts (Ward 7), Lincoln Heights/Richardson Dwellings (Ward 7), and Park Morton (Ward 1). Both local and federal funding will be needed to complete these redevelopments.

Three of the properties – Barry Farm, Lincoln Heights, and Park Morton – will be redeveloped through the New Communities Initiative, a partnership between the DC Housing Authority and the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development. The New Communities Initiative was begun in 2005 with ambitious plans to turn distressed public housing into mixed-income communities. Of five sites, one redevelopment has progressed, Northwest One, in Ward 6. That redevelopment demonstrates many of the issues highlighted in this report, including lagging replacement of public housing units.[15]

The New Communities Initiative redevelopment of Park Morton (Ward 1) is anticipated to begin in 2016. Park Morton will be redeveloped in phases: the site will be demolished and rebuilt part-by-part rather than all at once. A city-owned parcel close by will serve as a “build first” location, meaning some replacement units will be built ahead of time, for residents to relocate to as redevelopment progresses at the original site.

Plans for the other New Communities Initiative and DC Housing Authority-led redevelopments have not been finalized. This paper recommends that redevelopment plans use a phased approach, in combination with a “build first” approach if possible, to minimize disruption to residents and communities. Prompted by similar concerns over the redevelopment of the Greenleaf complex in Ward 6 – most of which is housing for seniors and people with disabilities – the DC Council has urged the DC Housing Authority to use a “build first” approach there.[16]

Redevelopment Important to Ensure Public Housing Quality, But Has Risks to Residents

Redevelopment of public housing carries two main risks: that residents will be displaced from their community and possibly lose affordable housing during construction; and that some residents won’t be able to return to and enjoy the new building.

Moving Can Disrupt Community Ties

The first risk is that the relocation process will displace residents from their community. Neighbors, family, churches, and local service providers are a valuable source of support for low-income families, especially for seniors, families with young children, and people with disabilities. While some families may benefit from new surroundings, being separated from social support networks for several years during construction can make the relocation period difficult for many.[17] Children may have to switch schools as a result of relocation, possibly in the middle of the school year, interrupting educational continuity.

The DC Housing Authority can minimize disruption to families during redevelopment by conducting the redevelopment in stages. For public housing developments with multiple buildings, that means not emptying out the entire development at once. Occasionally there may be nearby sites that can be used to build replacement apartments first, before demolishing the old building, known as a “build first” approach. If the entire development must be emptied of all residents at once, the housing authority should ensure families have affordable housing during relocation and can return to the property once it reopens.

Some Families May End Up Without Affordable Housing

A related risk is that some households may be left without affordable housing during redevelopment. It is difficult to specify how large of a risk this is in the District. However, two national studies of public housing redevelopments found that 14 percent to 18 percent of relocated households were no longer living in subsidized housing two to seven years after redevelopment began. Most of those families reported having trouble paying the rent.[18]

During redevelopment, residents may be relocated to other public housing properties, if there is space available. But typically households are given vouchers that help them pay rent in a private-market apartment. The household pays 30 percent of its income to the landlord, with the voucher covering the rest of the rent. Because housing authorities must offer residents one to three units as relocation options,[19] residents have help finding an apartment when they first move from the public housing property.

- Families need housing search assistance throughout the relocation period. Redevelopments often taken years, and sometimes a family will need to move from the first apartment offered by the housing authority. Large households with children and seniors may have trouble finding a place that both fits their needs and is eligible for voucher use.[20] There is a risk that some households may search unsuccessfully for a place to use their voucher, and end up living somewhere unaffordable or moving in with another family. The housing authority can reduce this risk by making sure families have access to housing search assistance, such as housing navigators and rental brokers, during the entire relocation period. The housing authority should also continue outreach and education to landlords and leasing agents to familiarize them with the process of leasing to families with rent vouchers and increase awareness of laws protecting voucher holders from discrimination.

- Moving expenses can strain family budgets. Beyond that, moving expenses can be burdensome for families that are temporarily relocated. The housing authority is required to reimburse relocated residents for moving costs. But what’s eligible for reimbursement isn’t consistent across redevelopments, so residents often don’t know what’s covered. For extremely low income families, paying for moving expenses up front can take a toll, cutting into the household budget during the period between paying the movers, and receiving reimbursement from the housing authority.

Barriers Can Prevent Households From Returning to Their Community

The second risk to residents when public housing is redeveloped is that households who were relocated and want to come back to the reopened property may not be able to do so. This can happen when the new building may not have the same number or kind of units as the old one, or when households have to go through additional screening before they can return.

The “right to return” means that a place is saved in the redeveloped property for each family who had to move away during construction. Many relocated households will want to come back to the community they call home. The right to return also ensures that the residents of the original property can benefit from the new, high-quality homes and mixed-income community created by the redevelopment.

The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which oversees local housing authorities, has requirements for whether each unit needs to be replaced in the redevelopment, and whether the housing authority has to save a place for families who moved away during construction. But the federal requirements vary based on which redevelopment program the housing authority uses, and aren’t always strong enough to ensure that every family who wants to can return to the new property. Both of the two main redevelopment programs, Demolition/Disposition, and Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD), require that the housing authority replace each public housing unit with another subsidized unit – called one-for-one replacement – but there are some exceptions.[21] Neither tool requires the housing authority to replace each unit with an equivalent unit with the same number of bedrooms.[22] Only RAD gives residents the right to return to the property once construction is finished.[23]

- Redeveloped properties should accommodate the original residents. Formalizing a right to return is important, but so is ensuring that it works in practice. In some cases, even if families have a right to return on paper, they may not be able to return if the redeveloped apartments no longer meet their needs, like having enough bedrooms for large families or having accessible features for residents with disabilities. Most redevelopments are required to replace units one-for-one. But a redevelopment could replace all three-bedroom apartments with one-bedroom apartments, for instance, and still be considered one-for-one replacement. For relocated households to be truly able to return to the new building and reconnect with their community, the housing authority should replace units one-for-one and preserve the mix of unit sizes and accessible units.

- Clear communication about return procedures is important. Lack of communication between residents and the housing authority can be a barrier to a practical right to return. Households may not be clearly informed that they have a right to come back, when the redeveloped property is expected to reopen, or if and when they must indicate they want to return. Consequently, households who want to return to the property may not know they can come back, or may inadvertently become ineligible to return. For instance, families may not be aware they could lose their spot in the reopened property unless they report an interest in returning by a certain date. They may be offered an option to move to another property before redevelopment is fully underway, and may not know that this relocation will be permanent and means giving up their right to return to the original site.

- Additional screening is a barrier to returning. Requiring additional screening before families can move back into a redeveloped apartment is another barrier to returning.[24] With variable incomes and family situations, many public housing residents are not compliant with their leases. Preventing lease noncompliant families from returning to the property, and requiring additional screening like credit checks which are very difficult for extremely low income households to pass, could result in removing households that otherwise wouldn’t be evicted. The risk of additional screening could be greater in redevelopments that involve transforming the property into a privately-owned mixed-income building, as private landlords may be more eager to impose rigorous screening. The burden of additional screening could largely fall on households with complex challenges who have few, if any, other housing options.[25]

Finally, there will be cases where residents will have to move to a new community no matter what – for instance, when the housing authority plans to demolish a property and locate all replacement units elsewhere in the city, at one or several sites. This type of redevelopment can be used to decrease the geographic concentration of public housing. However, residents should have a right to return to a public housing unit and be offered support during the time they’re temporarily relocated.

Recommendations

Public housing is an important but endangered source of affordable apartments for many seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children. Public housing properties in bad condition should be upgraded. But it’s important that redevelopment is done right. To ensure that residents continue to have stable, affordable housing, and can stay connected to the community they call home, the DC Housing Authority should adopt the following policies. The District should require that any public housing redevelopment utilizing local funding incorporate these resident protections, either through a Memorandum of Understanding between the District and the housing authority, or through DC Council legislation.

Ensure residents have a formal and practical right to return to the redeveloped property.

- Replace units one-for-one, and preserve the mix of unit sizes and accessible units from the original property. To truly ensure families can return to their community, the property’s ability to serve families with children, seniors, and people with disabilities should be maintained.

- Adopt a universal right to return policy that is available in writing and legally binding. In every public housing redevelopment, all relocated residents should have a formal right to return to the property – regardless of whether it is required by HUD.

- Provide a right of return to families moved out prior to, but in anticipation of, redevelopment. Households are sometimes relocated before HUD has reviewed the housing authority’s application to redevelop the site, which would trigger the right to return under some redevelopment programs (in the absence of the policy recommended above).[26] All families relocated after the housing authority has taken steps to move the redevelopment forward, such as selecting a development partner for the site or applying for zoning review, should have the right to return.

- Do not rescreen households before they can return to the new property. A family that resided on the property at the start of development and who is not part of active eviction proceedings should not be required to pass additional checks.

- Have a guidebook for relocated residents that includes information on the right to return policy, how and when residents will indicate they want to move back as redevelopment is completed, and contact information for legal advocates.

Redevelop large properties in phases, or if possible, build some units nearby first before demolishing the property.

- Redevelop in phases – by demolishing and rebuilding the site a part at a time where possible – rather than clearing the entire site at once and then beginning construction. This approach avoids displacing an entire community at one time, and can mean shorter relocation periods.

- Where possible, use nearby sites as “build first” locations. Constructing some replacement units there before moving all residents from the property could allow some residents to move directly to a new unit near the original site, skipping the relocation period. Most importantly, a “build first” approach ensures residents can stay in or close to the neighborhood they call home.

Ensure households have affordable housing during redevelopment.

- Provide housing search assistance for voucher holders during the entire relocation period. This could include access to housing navigators or rental brokers, and stipends for those who need help paying security deposits and moving expenses.

Improve communication with residents of properties slated for redevelopment.

Residents often do not feel they have enough input into the redevelopment plan, and aren’t sure when and where they will be relocated, or if they will be able to come back. While the DC Housing Authority has periodic meetings with residents of properties to be redeveloped, some resident advocates indicate that there is room for improvement in the quality of communication and discussion. Better communication will ensure residents are protected throughout the process and that redeveloped properties reflect residents’ needs with appropriate units for all who wish to come back. This, along with the recommendation below, would help ensure residents are part of the redevelopment process, rather than simply affected by it.

Develop written Relocation Plans in collaboration with residents and their advocates.

A relocation plan should cover all aspects of concern to residents, such as the redevelopment timeline and resident rights and responsibilities. The following information should be included in the plan: when relocation will begin; whether a resident will move to a private apartments with a voucher, or to another public housing property; how residents’ moving expenses will be covered; whether residents must indicate a wish to return by a certain date; and a full explanation of the residents’ right to return. HUD sometimes requires the DC Housing Authority to write a relocation plan for a given redevelopment,[27] but these plans may be inconsistent across properties, are not binding, and do not offer clarity to residents. This relocation plan should be binding, expansive, and accessible to residents.

Endnotes

[1] Only 8 percent of apartments in the Section 8 subsidy program in the District have three or more bedrooms. US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Picture of Subsidized Households, 2013.

[2] Renting for $800 or less. DCFPI analysis of 2013 American Community Survey, US Census Bureau.

[3] Mary Cunningham and Graham MacDonald, Urban Institute, “Housing as a Platform for Improving Education Outcomes among Low-Income Children,” May 2012.

Some public housing units with multiple bedrooms may still be crowded, according to advocates for public housing residents, because rooms are often small with two children placed per room.

[4] The main source of income for 9 percent of households is unknown.

[5] This is higher than the share of elderly or disabled headed households – this category (sources other than wage or welfare) includes other sources like unemployment benefits and child support, in addition to old age and disability benefits.

[6] US Social Security Administration, OASDI Beneficiaries by State and ZIP Code, Dec. 2014.

[7] US Social Security Administration, Congressional Statistics: Disability Insurance, Dec. 2014.

[8] Mary Cunningham and Graham MacDonald, Urban Institute, “Housing as a Platform for Improving Education Outcomes among Low-Income Children,” May 2012.

[9] Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, “The State of the Nation’s Housing,” 2015. Low-income households are defined as households in the bottom quartile of expenditures (average expenditures $15,650).

[10] US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Fair Market Rent Summary for the District of Columbia.

[11] DC households with incomes under 30 percent of the area median spend on average 69 percent of household income on rent. DC Fiscal Policy Institute analysis of 2013 American Community Survey microdata.

[12] DC Housing Authority FY 2016 Budget Oversight Documents, DC Council Committee of Housing and Community Development.

[13] DC Housing Authority 2015 Moving to Work Plan submitted to US Department of Housing and Community Development, May 2015.

[14] DC Housing Authority FY2016 Budget Oversight Documents, DC Council Committee of Housing and Community Development.

[15] In 2008, 250 public housing units were demolished as part of the Northwest One redevelopment. Documents from the New Communities Initiative indicate that as of January 2015, only 137 replacement units have been completed. The Northwest One redevelopment intends to replace an additional 211 public housing units, but the timeline for doing so has yet to be finalized.

[16] DC Council R21-317, “Sense of the Council Supporting a ‘Build First’ Model of Reinvestment in Greenleaf Public Housing Resolution of 2015.” Effective 1 December 2015.

[17] Urban Institute, “A Decade of HOPE VI: Research Findings and Policy Challenges,” 2004.

[18] Relocated families who ended up in unsubsidized housing had slightly higher incomes than those who remained in subsidized housing, but two thirds had income below 30 percent of the area median. Relocated households in unsubsidized housing were more likely to report having trouble paying rent and utilities, and were more likely to be doubled up with other families, than families who were in subsidized housing. This study examined resident outcomes two to seven years after redevelopment began.

Abt Associates and Urban Institute for the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, “HOPE VI Resident Tracking Study,” 2002. United States General Accounting Office, “HOPE VI Resident Issues and Changes in Neighborhoods Surrounding Grant Sites,” 2003. This study examined resident outcomes seven years after redevelopment began.

[19] Uniform Relocation Act, 49 CFR Part 24.

[20] Abt Associates for the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Study on Section 8 Vouchers Success Rates, Vol. I,” 2001.

[21] Public housing authorities may demolish up to 5 percent of their public housing units in a five year period without replacing them as housing units, if the space occupied by the demolished units is used to locate resident services. Redevelopments using RAD are permitted to replace only 95 percent of the units, and may further reduce the number of units by reconfiguring unit sizes or converting housing units into space for resident services, and by not replacing units vacant for two or more years. 24 CFR Part 970, “Public Housing Program – Demolition or Disposition of Public Housing,” Federal Register Vol. 71 No. 205 Effective 24 Oct. 2006. PIH Notice 2012-32 (HA) REV-2, “Rental Assistance Demonstration – Final Implementation, Revision 2,” US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Issued 15 June 2015.

[22] RAD rules do require public housing authorities to inform residents if the redevelopment plan would prevent them from returning, and if the resident objects, the housing authority must alter the plans to accommodate them. PIH Notice 2014-17, “Relocation Requirements under the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) Program, Public Housing in the First Component,” US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Issued 14 July 2014.

[23] PIH Notice 2014-17, “Relocation Requirements under the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) Program, Public Housing in the First Component,” US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Issued 14 July 2014.

24 CFR Part 970, “Public Housing Program – Demolition or Disposition of Public Housing,” Federal Register Vol. 71 No. 205 Effective 24 Oct. 2006.

Note: Redevelopments through Demolition/Disposition must include a right to return for lease-compliant households if the redevelopment utilizes a Choice Neighborhoods Implementation Grant. FR-5900-N-1, FY2013 Notice of Funding Availability, Choice Neighborhoods Implementation Grant Program, US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

[24] RAD rules prohibit rescreening before households can return. PIH Notice 2012-32 (HA) REV-2, “Rental Assistance Demonstration – Final Implementation, Revision 2,” US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Issued 15 June 2015.

[25] Urban Institute, “A Decade of HOPE VI: Research Findings and Policy Challenges,” 2004.

[26] PIH Notice 2014-17, “Relocation Requirements under the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) Program, Public Housing in the First Component,” US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Issued 14 July 2014.

[27] HUD requires public housing authorities applying for Demolition/Disposition of properties to write relocation plans. It strongly encourages, but does not require, housing authorities applying for RAD redevelopment to write relocation plans. 24 CFR Part 970, “Public Housing Program – Demolition or Disposition of Public Housing,” Federal Register Vol. 71 No. 205 Effective 24 Oct. 2006. PIH Notice 2014-17, “Relocation Requirements under the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) Program, Public Housing in the First Component,” US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Issued 14 July 2014.